Export diversification and the extensive margin of trade, defined as the number of products that are exported to foreign destinations, are important from a policy perspective (e.g. IMF 2014, Wijkman and Gylfason 2017, Canada 2018) and also in the academic literature (e.g. Helpman et al. 2008, Santos Silva et al. 2014, Cadot et al. 2011, Hummels and Klenow 2005). Export diversification is particularly important for smaller and poorer countries because their exports are less diverse. Since poorer/smaller countries export fewer products, they have more volatility in their terms of trade and are therefore more vulnerable to negative trade shocks.

In our paper (Anderson and Yotov 2022), we introduce the concept of the domestic extensive margin, defined as the number of products that are produced by a given country, and demonstrate that this domestic extensive margin allows us to identify the effects of globalisation and country-specific policies (e.g. taxes, exchange rates) – effects that had not been properly identified in the existing literature. In addition, using the domestic extensive margin allows us to re-evaluate the effects of bilateral policies (e.g. WTO membership, trade agreements) on export diversification.

Methods and data

The introduction of the domestic extensive margin has implications for measurement and identification. On the measurement front, we construct a novel index – the relative domestic extensive margin – which is the ratio of the number of products actually produced by a country in a given year to the total number of possible products that could have been produced by the same country in the same year. The relative domestic extensive margin reflects the fact that smaller and/or poorer countries cannot produce too many goods, thus allowing for consistent (relative) comparison of the extensive margins of trade across countries.

As expected, the relative domestic extensive margin index reveals that large and developed economies (e.g. Germany and France) produce almost all possible products, while smaller and/or poorer economies (e.g. Iceland and Northern Macedonia) only produce a small fraction (about 10–15%) of the products that could be produced. The evolution of the relative domestic extensive margin reveals that most countries have experienced a decrease in their relative domestic extensive margin indexes over time, a pattern consistent with specialisation (de-industrialisation).

From an estimation perspective, the domestic extensive margin allows us to identify the effects of globalisation (i.e. the evolution of bilateral trade costs over time) and country-specific policies and characteristics (e.g. export promotion, taxes, corruption, institutional quality) that cannot be identified properly with data on the international extensive margin only. Moreover, the domestic extensive margin delivers complementary estimates of the effects of bilateral trade policies (e.g. WTO membership, economic integration agreements, currency unions).

To highlight the policy importance of our methods, we construct a new database that covers the domestic and international extensive margins of trade for 35 European economies (1995–2014) and deploy it to estimate the effects of globalisation, EU integration, WTO membership, and economic integration agreements on export diversification and the extensive margin of trade. The data sources used are Eurostat’s PRODCOM and COMEXT, and we rely on the new PRODCOM-COMEXT concordance from Bradley et al. (2022), who construct a product-level database that includes international and domestic trade flows.

The econometric model we use includes exporter-time fixed effects, importer-time fixed effects, and asymmetric country-pair fixed effects, and we use the doubly-bounded FLEX estimator of Santos Silva et al. (2014). To estimate the effects of globalisation, we use time-varying border dummy variables, which take a value of one for international trade and zero for domestic sales for each year in the sample.

Policy implications

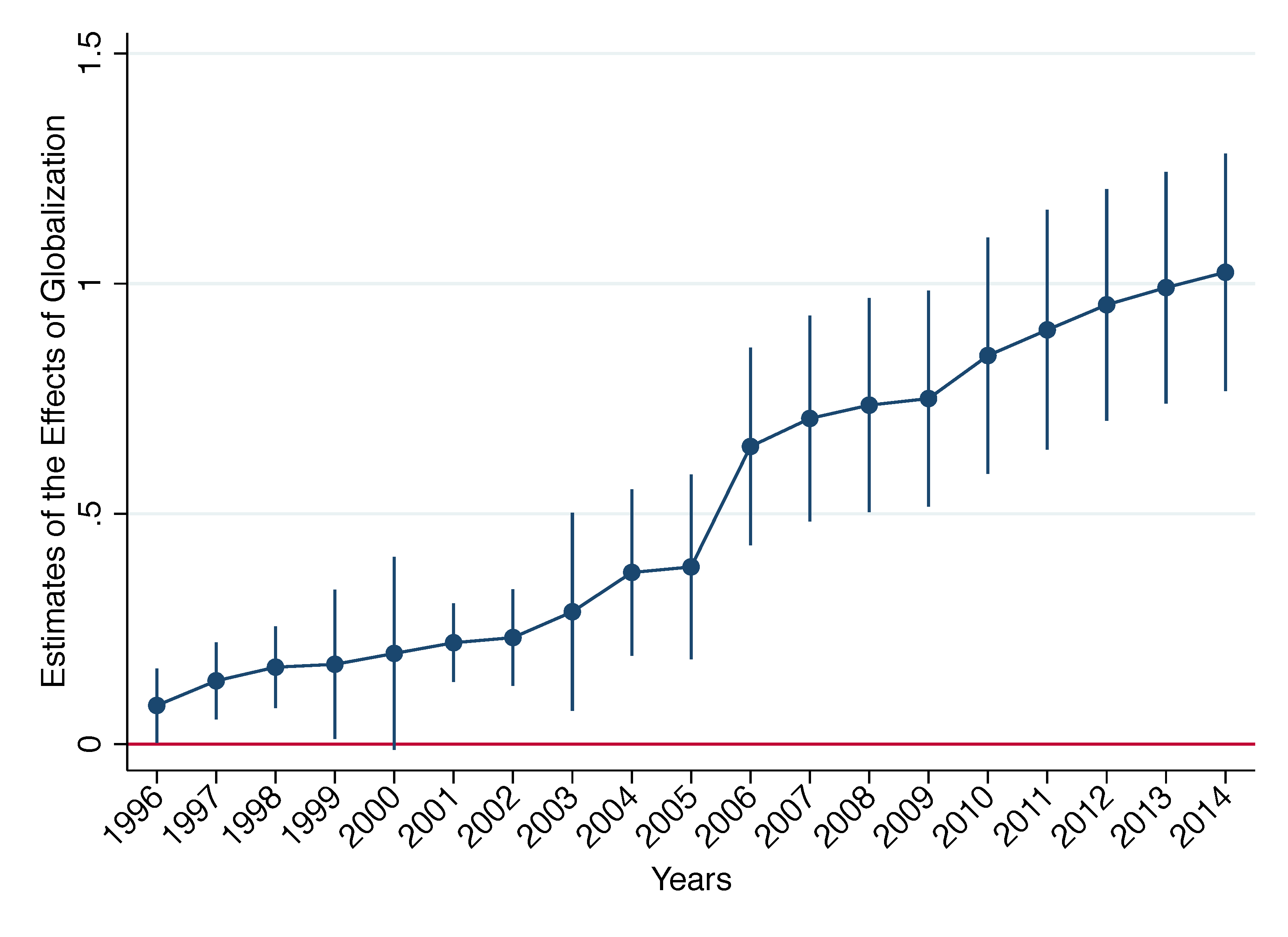

Several policy implications stand out. First, we find that the effects of globalisation on export diversification in Europe over 1995–2014 were very strong. This is captured in Figure 1, where we plot the estimates of the international border dummies in our model. Using the domestic extensive margin has enabled us to identify the impact of globalisation, even with the exporter-time and importer-time fixed effects in our econometric model. This is not possible when only data on the international extensive margin is used.

Figure 1 Globalisation and export diversification, Europe, 1995–2014

Notes: This figure plots the estimates of the coefficients on the time-varying border variables that capture the effects of globalisation, 1995–2014. All estimates are relative to the border effects in 1995 and should be interpreted accordingly. See text for further details.

Source: Anderson and Yotov (2022).

The estimates for each year in Figure 1 are relative to the effects of borders on European trade in 1995. Thus, the positive and increasing estimates in the figure suggest that the effects of international borders on export diversification in Europe have fallen steadily and significantly between 1995 and 2014. The policy/economic interpretation of our estimates is given by the marginal effect of the estimate for 2014, which, by construction, captures the total impact of globalisation during the period of investigation. This estimate implies that, on average, the number of internationally traded products increased by about 511 relative to the number of domestically traded products during the period of investigation, i.e. about 16% of the total number of possibly traded products in 2014.

Another implication is that the effects of globalisation on the extensive margin of trade were more resilient to negative shocks than the corresponding effects on the intensive margin of trade. For example, the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on the extensive margin is significantly milder than the impact on the intensive margin of trade reported in the related literature. We find this result intuitive because it is natural for firms to decrease the volume of trade, i.e. the intensive margin, before eliminating an existing trade relationship, i.e. the extensive margin.

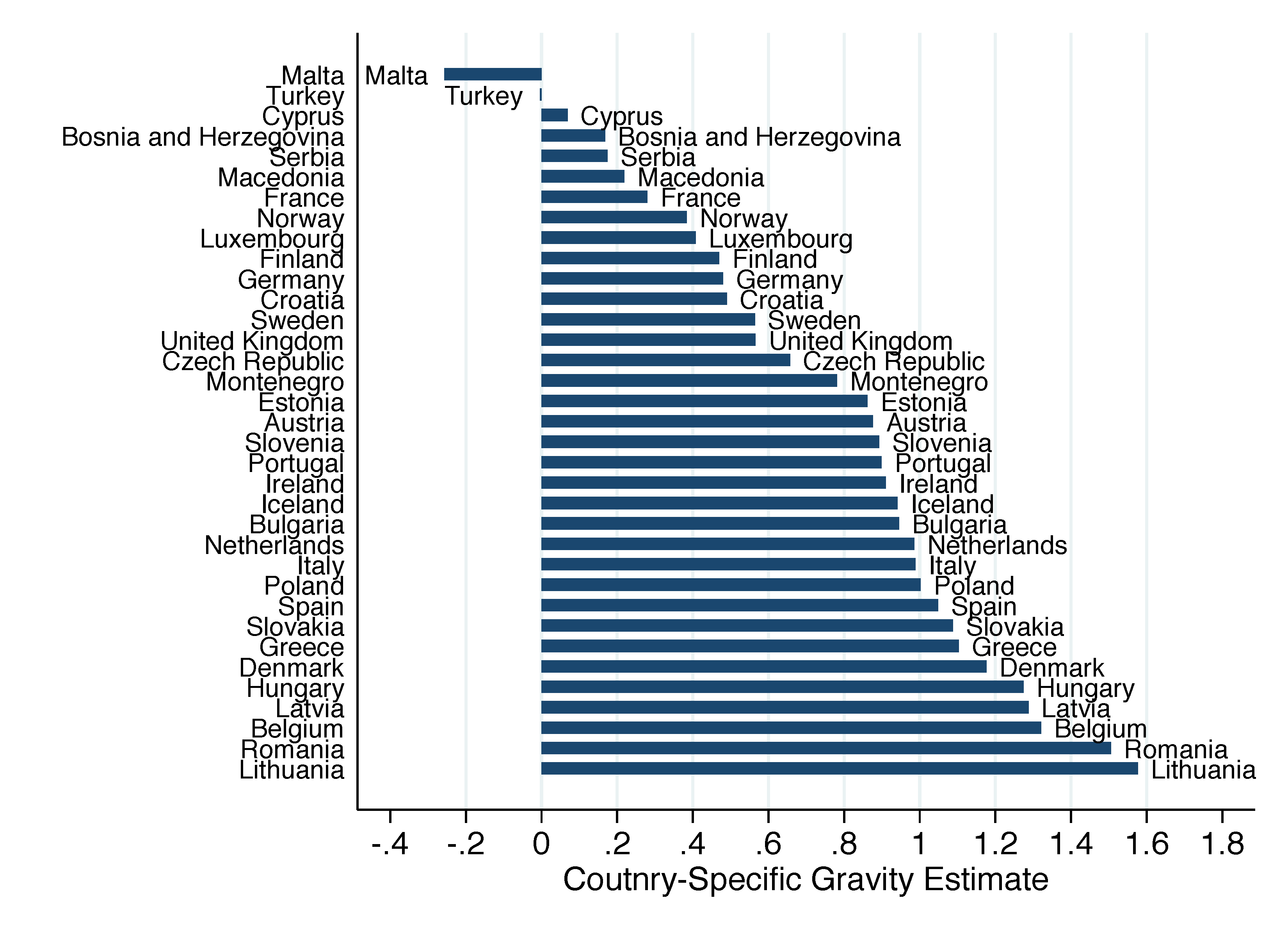

Figure 2 reports country-specific estimates of the effects of globalisation on export diversification. Almost all estimates are positive and sizeable, implying that globalisation has led to more traded products for all but two of the countries in our sample (Malta and Turkey). In addition, the effects of globalisation are heterogeneous across the countries in our sample. A tentative implication is that the biggest winners from European integration on the extensive margin were the small and poorer EU economies, especially those that recently joined the EU, while the large and old EU members have gained relatively little.

Figure 2 Country-specific globalisation effects, Europe, 2014

Notes: This figure plots the estimates of the coefficients on the country-specific border variables that capture the total effects of globalisation. All estimates are relative to the border effects in 1995 and should be interpreted accordingly. See text for further details.

Source: Anderson and Yotov 2022.

The heterogeneity in the country-specific estimates becomes more nuanced once we allow for asymmetric effects on the number of products exported from old EU members to new EU members versus the number of products imported by the old EU members from the new EU members. This analysis reveals significant asymmetries between the effects on the exports versus imports of old to new EU members. Specifically, the number of new products exported from the old to the new EU members grew significantly faster than the number of new products that were exported from the new to the old EU members. This implies that the new EU members benefitted from a large increase in product varieties from Western Europe; however, the new EU members were not able to position their (possibly inferior) products very well in the West-European market.

Finally, in addition to estimating the effects of globalisation and EU integration, we estimate the effects of membership in the WTO and economic integration agreements on export diversification. Three main results stand out. First, we find that joining the WTO or being a member of economic integration agreements had a positive impact on the extensive margin of trade.

Second, comparing WTO estimates with and without the domestic extensive margin reveals that the latter are much smaller and not statistically significant. This result contributes to the debate on the effects of the WTO on international trade (e.g. Rose 2004 and Larch et al. 2019a,b) and implies that gravity studies that do not account for the domestic extensive margin may underestimate the impact of bilateral trade policies on export diversification.

Finally, our country-specific WTO estimates reveal that joining the WTO has led to a larger number of traded products, not only between member countries but also between members and non-members. Importantly, the country-specific WTO effects could not be identified without the domestic extensive margin.

Conclusion and further implications

The new domestic extensive margin concept and our analysis point to opportunities for further research and policy investigations. First, our methods allow for an evaluation of the effects of non-discriminatory trade policies (e.g. export subsidies, export promotion) and country-specific characteristics (e.g. institutional quality, country-specific taxes) on export diversification and the extensive margin of trade – effects which could not be identified without using the domestic extensive margin.

Second, as demonstrated by our WTO estimates, the domestic extensive margin has implications for estimating the effects of bilateral trade policies (e.g. regional trade agreements, currency unions, and sanctions).

Third, exploring the effects of export diversification in poor countries would require the construction of new data that cover those countries.

Finally, we see value in the construction of a new index that measures relative export diversification, defined as the ratio of the number of exported products and the number of domestically produced products, which would complement the existing export diversification indexes that are constructed from only export data.

References

Anderson, J E, and Y V Yotov (2022), “Quantifying the extensive margin(s) of trade: The case of uneven European integration”, CESifo Working Paper 9822.

Bradley, S, J Florez, M Larch, and Y V Yotov (2022), “The granular trade and production activities (GRANTPA) database”, manuscript.

Cadot, O, C Carère, and V Strauss-Kahn (2011), “Export diversification: What’s behind the hump?”, Review of Economics and Statistics 93(2): 590–605.

Canada (2018), “Canada and the G20: Trade diversification. Context and purpose of Canada’s trade diversification strategy”, November.

Helpman, E, M Melitz, and Y Rubinstein (2008), “Trading partners and trading volumes”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(2): 441–87.

Hummels, D, and P J Klenow (2005), “The variety and quality of a nation’s exports”, American Economic Review 95(3): 704–23.

IMF (2014), “Sustaining long-run growth and macroeconomic stability in low-income countries – the role of structural transformation and diversification”, IMF Policy Paper.

Larch, M, J-A Monteiro, R Piermartini, and Y V Yotov (2019a), “On the effects of GATT/WTO membership on trade: They are positive and large after all”, School of Economics Working Paper Series 2019-4, LeBow College of Business, Drexel.

Larch, M, J-A Monteiro, R Piermartini, and Y V Yotov (2019b), “Trade effects of WTO: They’re real and they’re spectacular”, VoxEU.org, 20 November.

Rose, A K (2004), “Do we really know that the WTO increases trade?”, American Economic Review 94(1): 98–114.

Santos Silva, J M C, S Tenreyro, and K Wei (2014), “Estimating the extensive margin of trade”, Journal of International Economics 93(1): 67–75.

Wijkman, P, and T Gylfason (2017), “Double diversification”, VoxEU.org, 6 February.