Childhood obesity among two- to five-year-olds in the US rose from 5% to 10.4% between 1974 to 2000, with an upward tendency (Cawley 2015). Other Western countries show similar trends (e.g. Zellner et al. 2007 for Germany). An estimated $14.1 billion per year is spent in the US on higher medical-service needs for affected children (summarised in Cawley 2010). Most papers on the causes of childhood obesity focus on high calorie intake (e.g. Currie et al. 2010) and lack of physical activity (e.g. Kimm et al. 2005, Cawley et al. 2012). In a recent paper (Dustmann et al. 2022), we investigate an additional, underexplored, potential cause of childhood obesity: insufficient exposure to sunlight – the primary source of vitamin D for children and adults (e.g. Hossein-Nezhad and Holick 2013) – and the resulting vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and early life.

Data and research design

We use data from compulsory examinations and health screenings undertaken by paediatricians for all children prior to school entry at age six in three federal states in Germany over nearly two decades. We combine this data source with information on daily sun hours at the district level. To obtain the causal effects of sun intensity on childhood obesity during pregnancy and different stages of a child’s life, our research design eliminates confounding factors such as district of birth, which may be correlated with children’s health through differences in lifestyles or diets; year of birth, which may be correlated with children’s health through business cycle effects (Dehejia and Lleras-Muney 2004); and month of birth, which existing research has shown to correlate with demographic characteristics that are themselves correlated with obesity (Currie and Schwandt 2013).

Findings

We show that 100 hours more sunshine in the first six months after birth – which is equivalent to the increased sun intensity from a two-and-a-half-week-long holiday in winter to a destination with sunshine similar to that in summer – reduce the risk of being overweight at age six by 1.1% and severe obesity at age six by 6%. These estimates imply 1,119 fewer overweight and 420 fewer severely obese children per birth cohort (677,947 children were born in 2010 in Germany) for 100 additional sunshine hours in the first six months after birth. By contrast, increased sunshine hours in the second half of the child’s first year and beyond have no detectable impact on being overweight or severely obese at age six. Increased sun intensity in the last trimester of pregnancy also tends to reduce the risk of subsequent adiposity, but this effect is smaller in magnitude than that of sun intensity in the first six months of life and statistically significant in only some specifications.

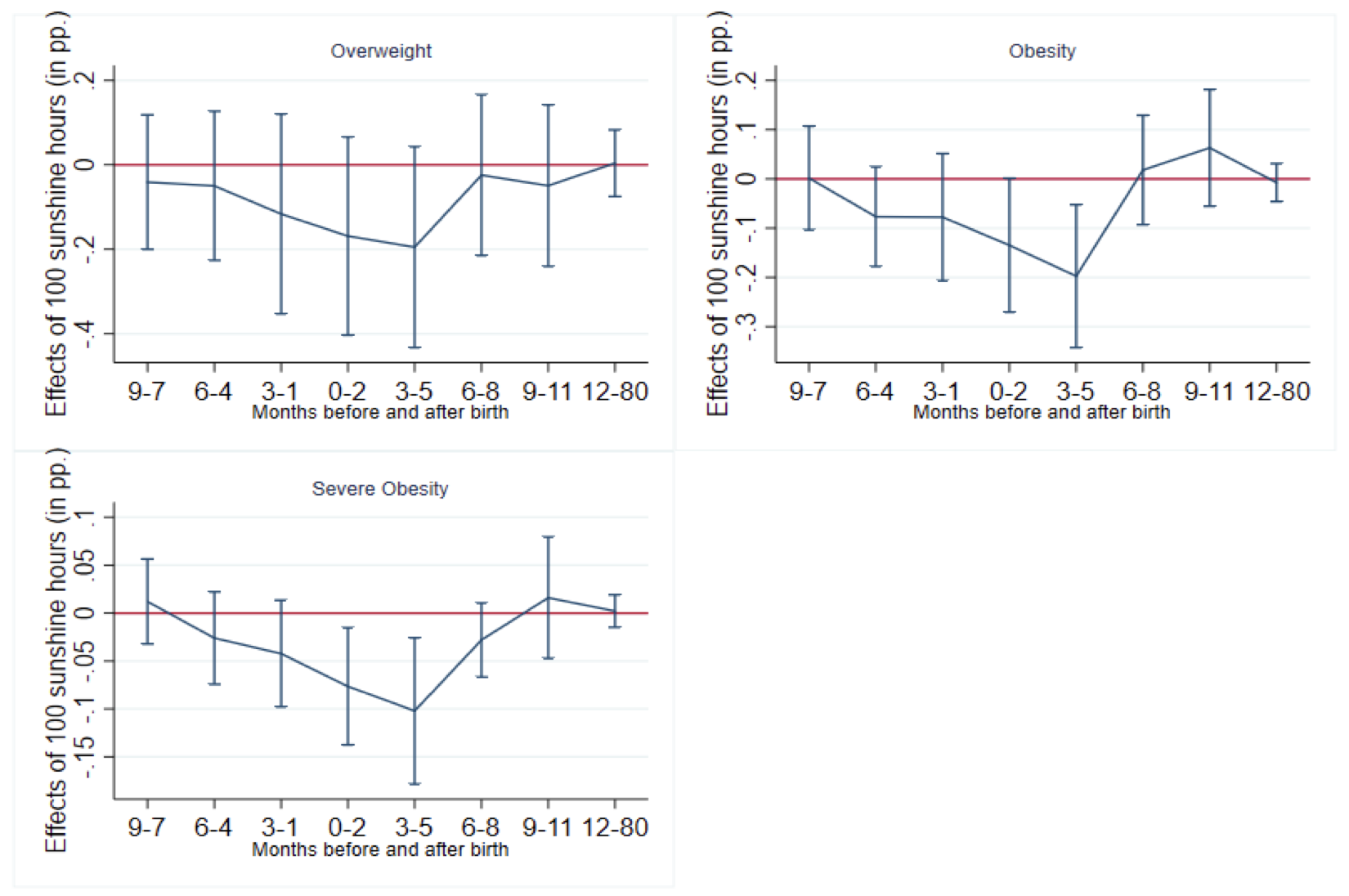

Figure 1 visually illustrates these findings, distinguishing eight intervals: seven three-month intervals ranging from the beginning of pregnancy to the end of the child’s first year, and one interval from the child’s first birthday until she is 80 months old. Sunshine hours in the first six months of life (i.e. in intervals 0–2 and 3–5) reduce the risk of adiposity at age six. By contrast, increased sunshine hours in months six to eleven after birth or beyond the child’s first year do not have a significant impact on childhood adiposity. In terms of magnitude, 100 additional sunshine hours in months three to six after birth reduce the risk of being overweight, obese, or severely obese by 0.19, 0.18, and 0.09 percentage points or 1.3, 3.6, and 9%, respectively.

Figure 1 Effects of sunshine hours during pregnancy and first years of life on adiposity risk at age six

Notes: The figures show the effects of 100 additional sunshine hours in percentage points (pp) in three-month intervals from conception to 11 months after birth, and between 12 and 80 months after birth, on children’s risk of being overweight, obese, and severely obese. Overweight, obesity, and severe obesity are defined, respectively, as >=85th, >=95th, and >=99th percentile in the gender- and age- (in months) specific BMI distributions. The red horizontal line depicts a zero effect. The vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals.

Data sources: School entry examinations, Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony. Sunshine hours from 21 weather stations.

We offer two explanations for why sunshine in the first six months after birth – and to lesser extent, in the third trimester of pregnancy – are most preventive for later obesity. First, the first six months of life (and possibly the third trimester of pregnancy) are a sensitive period, when infants rapidly gain weight and adipose tissue develops. Second, infants’ vitamin D levels are particularly sensitive to sunshine in the first six months of life, when lactation is highest.

Discussion and policy implications

Overall, our analysis highlights that increased sun intensity in the first six months of life may have a preventive impact on obesity, most likely through raising vitamin D levels. These findings have important public health implications, as vitamin D intake can be increased easily and at low cost through dietary supplements.

References

Cawley, J (2010), “The economics of childhood obesity”, Health Affairs 29(3): 364–371.

Cawley, J (2015), “An economy of scales: A selective review of obesity's economic causes, consequences, and solutions”, Journal of Health Economics 43: 244–268.

Cawley, J, D Frisvold and C Meyerhoefer (2012), “Physical education requirements and childhood obesity”, VoxEU.org, 26 September.

Currie, J, S DellaVigna, E Moretti and V Pathania (2010), “The effect of fast food restaurants on obesity and weight gain”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2(3): 32–63.

Currie, J and H Schwandt (2013), “Within-mother analysis of seasonal patterns in health at birth”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(30): 12265–12270.

Dehejia, R and A Lleras-Muney (2004), “Booms, busts, and babies' health”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(3): 1091–1130.

Dustmann, C, M Sandner and U Schönberg (2022), “The effects of sun intensity during pregnancy and in the first 12 months of life on childhood obesity”, forthcoming in The Journal of Human Resources.

Hossein-Nezhad, A and M F Holick (2013), “Vitamin D for health: a global perspective”, Mayo Clinic Proceedings 88(7): 720–755.

Kimm, S Y S, N W Glynn, E Obarzanek, A M Kriska, S R Daniels, B A Barton and K Liu (2005), “Relation between the changes in physical activity and body-mass index during adolescence. A multicentre longitudinal study”, The Lancet 366(9482): 301–307.

Zellner K, G Ulbricht and K Kromeyer-Hauschild (2007), “Long-term trends in body mass index of children in Jena, Eastern Germany”, Economics & Human Biology 5(3): 426–434.