Considering the apparent lack of a fundamental value (Papsdorf et al. 2022), the exponential growth in the volume of transactions involving Bitcoin and in its price is certainly surprising. After an initial popularity among a small community of experts, the usage of Bitcoin has been subsequently driven by the black market of illegal goods and services and by gambling (Foley et al. 2019, Marmora 2021). More recently, however, the soaring popularity of cryptocurrency exchange markets and Bitcoin might have also been driven by speculative motives (Baur et al. 2018) or, possibly, by its potential use for cross-border transactions and transfers (Graf von Luckner et al. 2023, Makarov and Schoar 2021), although the high volatility of its price makes Bitcoin impractical as a medium of exchange (Baur and Dimpfl 2021).

The popularity of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies has not been confined to few economies, but it has morphed into a global phenomenon, with emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) at the forefront of crypto adoption (Chainanalysis 2022).

To what extent is Bitcoin usage a global phenomenon driven by speculative demand? To what extent can country-specific factors explain the use of Bitcoin? These are important questions for policymakers, both to assess the potential risks from cryptoassets and to decide how to regulate the crypto ecosystem, that so far have received only partial answers (Makarov and Schoar, 2021, Kawashima et al. 2022), largely due to the difficulty to trace who owns and trades cryptocurrencies.

To answer these questions, in a recent study (Di Casola et al. 2023), we overcome the obstacle of limited country-by-country information on cryptocurrency analysing trading volumes of Bitcoin against the fiat currencies of 14 advanced economies (AEs) and the currencies of 30 EMDEs in the largest peer-to-peer (P2P) exchanges (LocalBitcoins and Paxful), over the period January 2018 to April 2022.

Peer-to-peer exchanges perform transactions outside the blockchain network (i.e. they are off-chain) in a decentralised manner, target mainly small retail users, and are usually not affected by the problem of market manipulation, such as wash trading, typical of centralised exchanges (Cong et al. 2023), thus making the transactions we analyse more reliable.

Peer-to-peer exchanges have gained popularity in particular in emerging markets and developing economies, being more suitable for their currencies that do not have a large trading pool to be easily used in centralised crypto exchanges (Aramonte et al. 2022).

A global crypto cycle driven by speculative motives

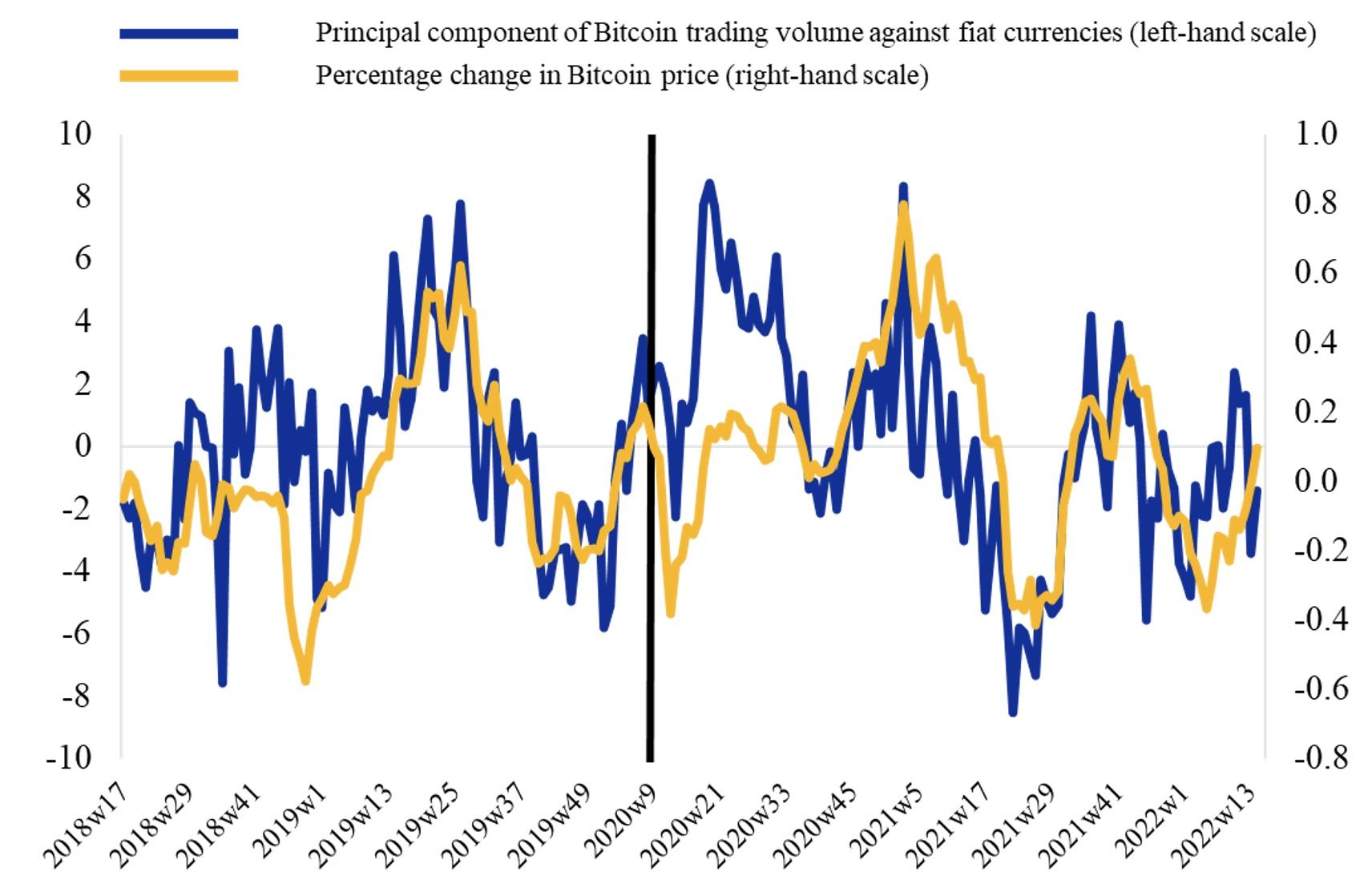

In our empirical analysis, we find that momentum and volatility in the crypto-asset market as well as global financial market volatility and liquidity do matter for Bitcoin trading against different fiat currencies, including those of advanced economies. However, our crypto-assets and global drivers fail to capture the full extent of co-movement in Bitcoin trading across currencies and over time. Indeed, our analysis identifies a single global factor that on average explains up to around 40% of the variance of Bitcoin trading across different currencies in the Covid-19 period. There is therefore suggestive evidence of a global crypto cycle in Bitcoin transactions, echoing the findings of the global financial cycle literature for traditional asset markets (Miranda-Agrippino and Rey 2022). This global factor, in turn, is correlated with the Bitcoin price, as shown in Figure 1. Trading across currencies and users around the world moves in tandem with fluctuations in the Bitcoin price, suggesting that Bitcoin is largely used as a speculative investment asset across advanced, emerging, and developing economies.

Figure 1 A global factor in Bitcoin trading volumes against fiat currencies is correlated with the Bitcoin price

Notes: The figure shows the first factor extracted from the trading volume of Bitcoin transactions against fiat currencies (blue line) and the change in the Bitcoin price (yellow line). Trading volumes and the Bitcoin price are detrended with the log difference with respect to the past 15-week moving average.

In emerging and developing economies, other factors do matter for Bitcoin trading

Bitcoin seems to offer also some transactional benefits, in particular in emerging markets and developing economies. The depreciation of the domestic currency of EMDEs – notably not of the currencies of advanced economies – induces more Bitcoin trading, in particular since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. This indeed suggests that Bitcoin, despite its wide price fluctuations, might have been appreciated also as a store of value or medium of exchange in countries which experienced a loss in the purchasing power of their domestic currency. In turn, this implies that macroeconomic instability may potentially spur greater cryptoasset usage. This result is important for the asset pricing theory of cryptoassets (Biais et al. 2023), suggesting that the fundamental value of Bitcoin may be substantially different between advanced economies and emerging and developing economies, since its transactional services are probably more elevated in the latter group of countries. Moreover, we find that proxies of banking depth and digitalisation are negatively correlated with the extent to which each currency loads on the global common factor in Bitcoin trading volumes, indicating that crypto-assets may offer a speculative alternative to traditional finance when this is not available, in particular in emerging and developing economies where the share of younger risk-prone population is higher.

Policy implications

Our findings clearly point to potential financial stability risks in emerging and developing economies with low levels of financial development and unstable fiat currencies. The intrinsic price volatility of Bitcoin may discourage its use as a store of value or means of payment. However, in the future, other crypto-assets, such as stablecoins that pledge to ensure a parity to the US dollar or other reserve currencies, might become more widely used by individuals and firms in order to compensate for the lack of financial alternatives, raising the risk of cryptoisation, i.e. the substitution of the domestic currency with a cryptocurrency – representing a threat to the implementation of capital flow management policies in these countries (He et al. 2022).

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank.

References

Aramonte, S, H Wenqian and A Schrimpf (2022), “Tracing the Footprint of Cryptoization in Emerging Market Economies”, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Auer, R and D Tercero-Lucas (2021), “Distrust versus speculation? The drivers of cryptocurrency investments”, VoxEU.org, 6 October.

Baur, D G and T Dimpfl (2021), “The Volatility of Bitcoin and its Role as a Medium of Exchange and a Store of Value”, Empirical Economics 61(5): 2663–2683.

Baur, D G, K H Hong and A-D Lee (2018), “Bitcoin: Medium of Exchange or Speculative Assets?”, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 54: 177–189.

Biais, B, C Bisiere, M Bouvard, C Casamatta and A J Menkveld (2023), “Equilibrium bitcoin pricing”, The Journal of Finance 78(2): 967–1014.

Chainanalysis (2022), The 2022 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report.

Cong, L W, X Li, K Tang and Y Yang (2023), “Wash trading in centralised crypto exchanges: The need for transparency and accountability”, VoxEU.org, 17 April.

Di Casola, P, M M Habib and D Tercero-Lucas (2023), “Global and local drivers of Bitcoin trading vis-à-vis fiat currencies”, ECB Working Paper 2868.

Foley, S, J R Karlsen and T J Putninš (2019), “Sex, Drugs, and Bitcoin: How Much Illegal Activity is Financed Through Cryptocurrencies?”, The Review of Financial Studies 32(5): 1798–1853.

Graf von Luckner, C, C M Reinhart and K S Rogoff (2023), “Decrypting New Age International Capital Flows”, Journal of Monetary Economics 138: 104-122.

He, D, A Kokenyne, X Lavayssière, I Lukonga, N Schwarz, N Sugimoto and J Verrier (2022), “Capital Flow Management Measures in the Digital Age: Challenges of Crypto Assets”, IMF Fintech Notes 5.

Kawashima, Y, R Mittal and E Feyen (2022), “The ascent of crypto assets: Evolution and macro-financial drivers”, VoxEU.org 19 March.

Makarov, I and A Schoar (2021), “Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market”, NBER Working Paper 29396.

Marmora, P (2021), “Currency Substitution in the Shadow Economy: International Panel Evidence using Local Bitcoin Trade Volume”, Economics Letters 205, 109926.

Miranda-Agrippino, S and H Rey (2022), “The Global Financial Cycle”, in G Gopinath, E Helpman and K Rogoff (eds.), Handbook of International Economics: International Macroeconomics 6, Elsevier, pp. 1–43.

Papsdorf, P, J Schaaf and U Bindseil (2022), “The Bitcoin challenge: How to tame a digital predator”, VoxEU.org 7 January.