Following the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, inflation resurfaced around the globe, representing the first time many individuals experience inflation substantially above central banks’ targets. Surges in inflation encountered during lifetime can trigger upward revisions of inflation expectations (e.g. Malmendier and Nagel 2016, Goldfayn-Frank and Wohlfahrt 2020). Yet, average inflation expectations of households have been biased upwards relative to ex-post realisations and central banks' targets, despite the fact that inflation rates have been low and stable for decades (e.g. Malmendier et al. 2022, Weber et al. 2022, D’Acunto et al. 2023). In a new study (Braggion et al. 2023), we propose that inflation shocks in the more distant past shape contemporary inflation expectations, potentially explaining why inflation expectations are higher than implied by lifetime inflation experiences. Such long-term effects of inflation would complicate the job of central banks and governments to manage inflation expectations and would suggest higher costs of disinflationary policies than standard models predict.

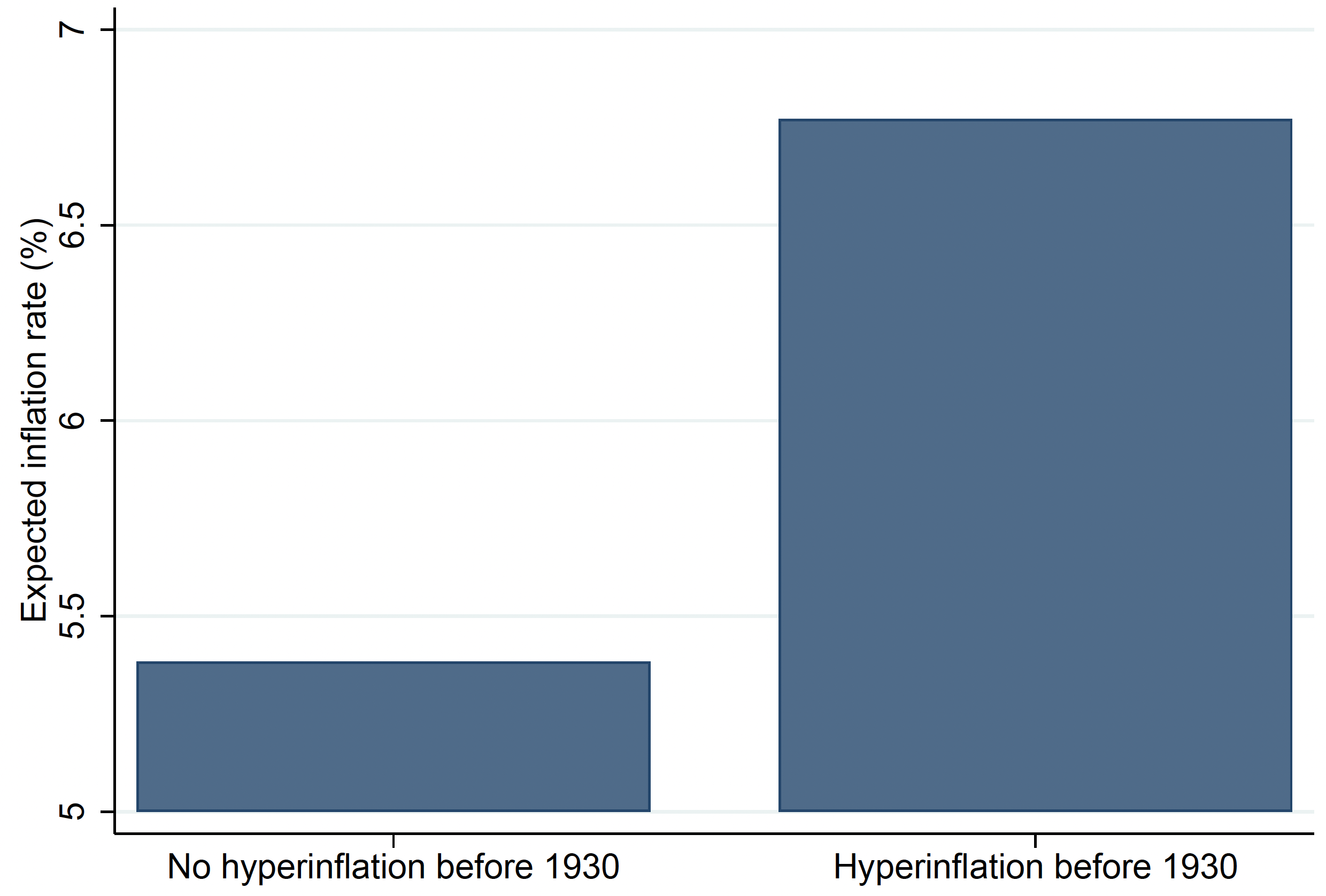

As motivating evidence, Figure 1 shows households’ inflation expectations in 2022 for 2023 separately for European countries that did not experience an episode of hyperinflation before 1930 (left bar) and for those that did experience one before 1930 (right bar). We find that individuals living in countries with hyperinflation in the distant past have inflation expectations that are approximately 1.4 percentage points higher than the inflation expectations of individuals living in countries without such a history. This provides first suggestive evidence that inflation expectations are shaped by inflation shocks in the distant past.

Figure 1 Past hyperinflations and today’s inflation expectations

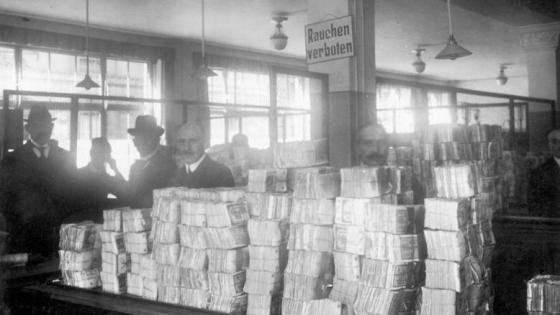

Germany as a laboratory

To study the long-term effects of inflation shocks in detail, we focus on Germany. Germany provides close to an ideal setting for such an investigation for two main reasons. First, the country experienced severe hyperinflation in 1922-1923, and rich anecdotal evidence suggests that this time period shapes Germans’ attitudes towards inflation to this day. However, only very few individuals alive today experienced the hyperinflation themselves. Thus, this setting enables us to study potential long-term effects of a major inflation shock. Second, we have granular data on realised inflation at the local level during the German hyperinflation and on today’s inflation expectations of households. In particular, we collect data on local inflation of 633 German towns between 1920 and 1924. Data on contemporary inflation expectations of households stem from three large-scale surveys, the Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung (GfK) Consumer Climate MAXX survey, Deutsche Bundesbank’s Panel on Household Finances (PHF), and the Bundesbank Online Panel – Households (BOP-HH). Linking today’s inflation expectations with historical inflation either at the zip code level or at the county level allows us to analyse whether local inflation during the German hyperinflation is correlated with local inflation expectations today.

Germans living in areas with higher historical inflation expect higher inflation today

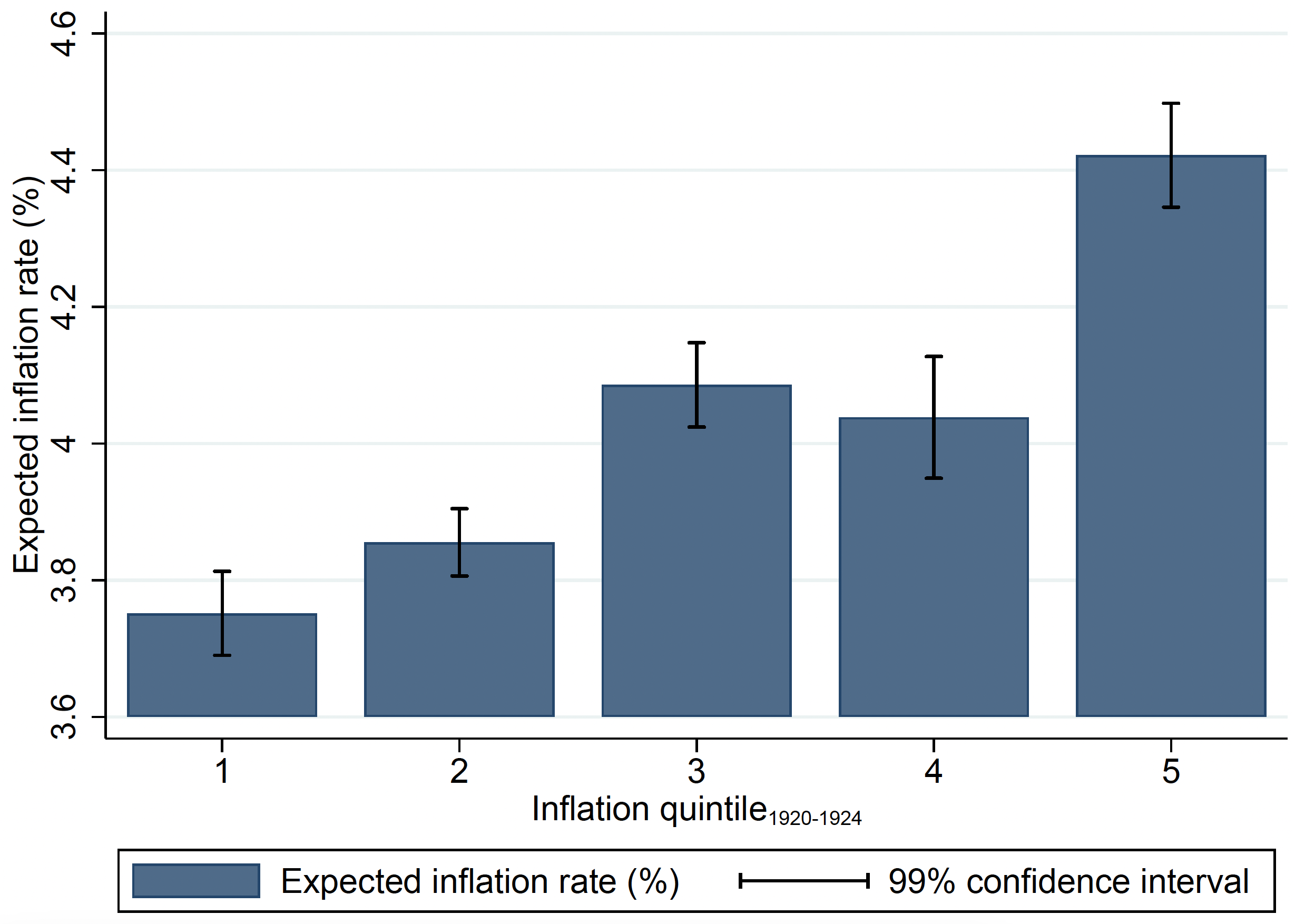

Figure 2 visualises our main finding in the raw data. We sort towns in Germany into quintiles based on their cumulative inflation between 1920 and 1924. For each quintile, we compute the average inflation expected by households living in those towns today. We then plot average inflation expectations against historical inflation quintiles. Consistent with Figure 1, we find a positive relationship between historical inflation and contemporary inflation expectations. This association suggests that individuals living in towns with high inflation in the 1920s expect higher inflation today. Moving from the quintile with the lowest realised inflation in the 1920s to the quintile with the highest inflation increases expected inflation today by 0.7 percentage points, which corresponds to around 90% of the average realised annual rate of inflation during the time period covered by our surveys. More formal regression-based analyses confirm this result. Additional tests suggest that the documented effect is not driven by local inflation being persistent over time or by historical inflation proxying for other macroeconomic experiences. Thus, our analysis points towards a long-lasting effect of inflationary shocks on inflation expectations.

Figure 2 Local inflation in the 1920s and today’s inflation expectations

Intergenerational transmission or collective memory?

There are at least two, not mutually exclusive mechanisms through which the experience of the German hyperinflation could persist locally across generations. The first channel is the intergenerational transmission of the experience of the hyperinflation from parents to their children. Existing research provides evidence for an intergenerational transmission of economic preferences (e.g. Dohmen et al. 2012, Chowdhury et al. 2022, Knüpfer et al. 2023). The second channel that could drive results is the transmission of inflation experiences over time through local institutions that create a collective memory. One such local institution is the media, which is known to shape public narratives and beliefs about historical events (e.g. Wohlfahrt et al. 2021, Andre et al. 2022, Goetzmann et al. 2022). Moreover, media coverage of inflation also matters for inflation expectations (e.g. Lamla and Lein 2014, Larsen et al. 2021). We provide evidence for both channels contributing to the transmission of inflation experiences across generations.

In additional tests, we show that differential historical inflation also modulates the updating of expectations to current inflation, the response to unconventional fiscal policies, and financial decisions.

Are these effects unique to Germany?

Germans are known to care a lot about inflation and might thus behave differently from households in other countries (e.g. Shiller 1997). The motivating evidence in Figure 1 already suggests that the results we find might not be limited to Germany. To test the generalisability of our findings more directly, we rerun our main analysis using data on Polish households. This is possible because a significant share of contemporary Poland was part of Germany during the hyperinflation. The estimates obtained for Polish households are similar in size to the ones for German households, albeit statistically weaker. Effects for Polish households are particularly pronounced in areas with less migration after WW2. Thus, our findings do not seem to be unique to Germany.

Conclusion

We show that inflationary shocks have a long-lasting impact on attitudes towards inflation. This provides an explanation for the well-documented upward bias in households’ inflation expectations. Our results have important implications for monetary and fiscal policy as managing inflation expectations becomes more difficult and costly if inflation experiences persist over a very long time.

References

Andre, P, I Haaland, C Roth, and J Wohlfart (2022), “Narratives about the macroeconomy”, Working paper, briq – Institute on Behavior & Inequality.

Braggion, F, F von Meyerinck, N Schaub, and M Weber (2023), “The long-term effects of inflation on inflation expectations”, Working Paper, Tilburg University.

Chowdhury, S, M Sutter, and K F Zimmermann (2022), “Economic preferences across generations and family clusters: A large-scale experiment in a developing country”, Journal of Political Economy 130: 2361-2410.

D’Acunto, F, U Malmendier, and M Weber (2023), “What do the data tell us about inflation expectations?”, Chapter 5 in R Bachmann, G Topa, and W van der Klaauw (eds), Handbook of Economic Expectations, Academic Press.

Dohmen, T, A Falk, D Huffman, and U Sunde (2012), “The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust”, Review of Economic Studies 79: 645-677.

Goetzmann, W, D Kim, and R J Shiller (2022), “Crash narratives”, NBER Working Paper.

Goldfayn-Frank, O and J Wohlfart (2020), “Expectation formation in a new environment: Evidence from the German reunification”, Journal of Monetary Economics 115: 301-320.

Knüpfer, S, E Rantapuska, and M Sarvimäki (2023), “Social interaction in the family: Evidence from investors’ security holdings”, Review of Finance 27: 1297-1327.

Lamla, M and S M Lein (2014), “The role of media for consumers’ inflation expectation formation”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 106: 62-77.

Larsen, V H, L A Thorsrud, and J Zhulanova (2021), “News-driven inflation expectations and information rigidities”, Journal of Monetary Economics 117: 507-520.

Malmendier, U and S Nagel (2016), “Learning from inflation experiences”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 53-88.

Malmendier, U, M Weber, and F D’Acunto (2022), “Learning about inflation expectations from the data”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.

Shiller, R J (1997), “Why do people dislike inflation?”, in C D Romer and D H Romer (eds), Reducing inflation: Motivation and strategy, University of Chicago Press.

Weber, M, F D’Acunto, Y Gorodnichenko, and O Coibion (2022), “The subjective inflation expectations of households and firms: Measurement, determinants, and implications”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 36: 157-184.

Wohlfart, J, I Haaland, C Roth and P Andre (2021), “Inflation narratives”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.