Around the world, tight labour markets and high migration pressure have highlighted the effect of immigration barriers on firms and workers. Economists typically find that high-skill immigration positively impacts native workers (e.g. Peri et al. 2014) and restrictions on foreign high-skill hiring have little benefit (Mayda et al. 2018). But there is much less agreement about the effect of the least-skilled immigrant workers on the least-skilled natives (National Academies 2017, Edo et al. 2020).

A key source of this disagreement is the variety of strategies used to distinguish causation from correlation (Dustmann et al. 2016). In new research, we estimate the effect of immigration for low-skill work in a relatively transparent setting: by comparing the outcomes of ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ firms in a nationwide, firm-level randomised lottery of the principal US work visa for low-skill jobs (Clemens and Lewis 2022).

The study of exogenously (randomly) allocated visas has advantages beyond providing credible causal estimates of their impact. Typical research rigorously investigates the effects of immigration for low-skill work not with exogenous differences in policy restrictions, but with exogenous differences in migration itself. The workhorse research design uses spatial variation in migration flows produced by prior migrant settlement, independent of local economic conditions (e.g. Card 1990, Monras 2021).

But such estimates need not come close to the policy relevant treatment effect that is informative about a specific change in immigration policy (Heckman and Vytlacil). For example, it is plausible that a marginal expansion in low-skill work visas would be incident upon firms using a production technology in which native-born workers are poor substitutes for immigrants (hence such firms’ willingness to engage in costly foreign recruiting). There is little reason to think this technology would be the same as the technology of firms that happen to be located where immigrants settled in the past. Variation in immigration flows and variation in policy barriers can thus yield two, fundamentally different treatment effects. The most relevant estimates of the effect of policy come from exogenous variation in policy itself.

A random lottery for low-skill work visas

We study exogenous variation in immigration policy barriers to hiring foreign workers for low-skill jobs faced by US firms. Each year, firms in the US apply to the federal government for permits to hire foreigners in temporary jobs that do not require a high school degree. This H-2B visa is by far the largest visa programme for low-skill work in the non-farm economy. About 100,000–130,000 such permits are given each year across the country in industries including groundskeeping, hospitality, forestry, seafood processing, manufacturing, and construction.

Hiring of these workers is restricted by a quota that tightly binds, that is, it is typically far below annual demand for such workers. As a result, firms enter a randomised lottery to pass a key step in the application process for these work visas.

This makes it possible to observe what happens to groups of firms that can or cannot hire foreign labour for low-skill work, but otherwise start out identical. To do this, we designed and implemented a survey of firms that entered the January 2021 lottery, collecting data in and after October 2021 on firm performance during April–September 2021. Before any survey responses were received, we irreversibly posted a pre-analysis plan specifying the principal hypotheses to be tested and the subgroups we would create to explore heterogeneous effects of the lottery.

Random loss of foreign employment causes firms to contract

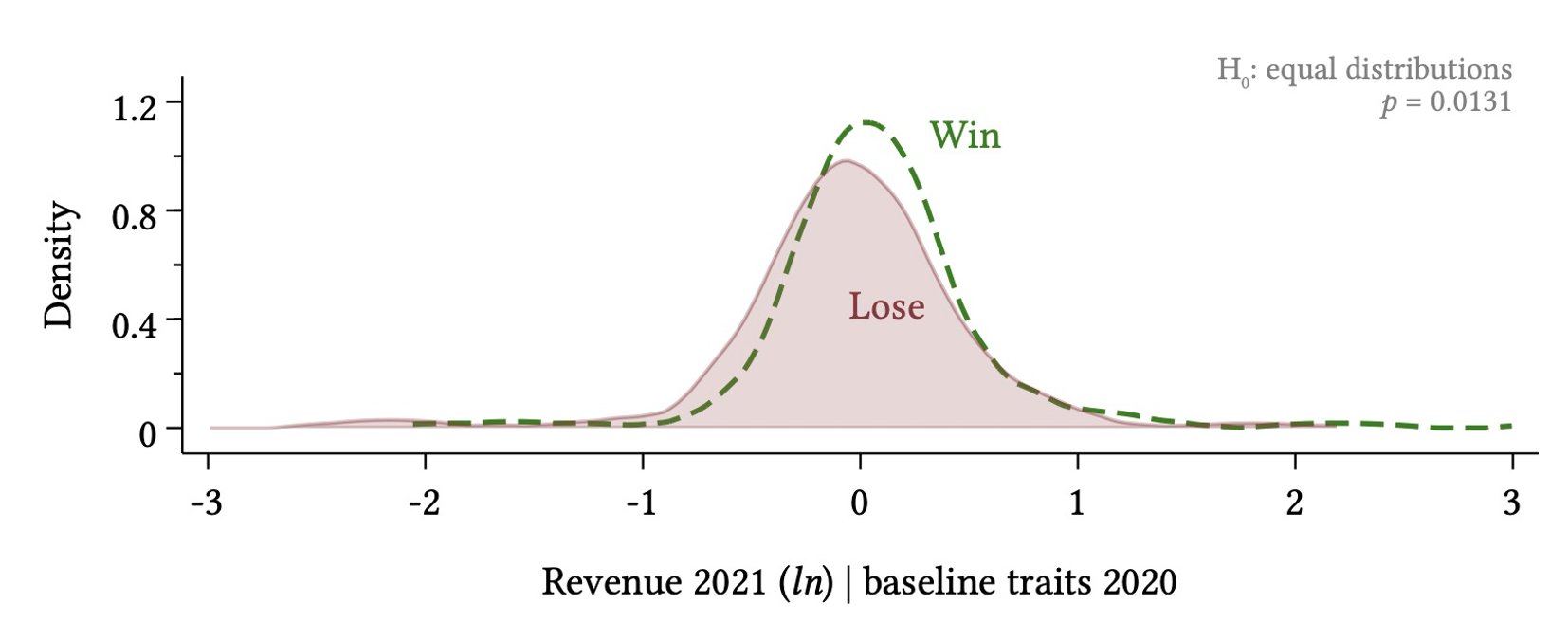

One key finding of the study is that firms slash production when they are barred at random from hiring immigrants for low-skill work. When this force majeure obliges otherwise identical firms to reduce foreign hiring by 56%, they slash production by 18%.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of log revenue in 2021, conditional on predetermined baseline traits. The dashed green line shows firms that ‘win’ the lottery and can thus hire their desired number of foreign workers. The solid red line shows firms that ‘lose’ the lottery and are thus obliged to hire far fewer foreign workers. A statistical test rejects the equality of these distributions with almost 99% confidence.

Figure 1

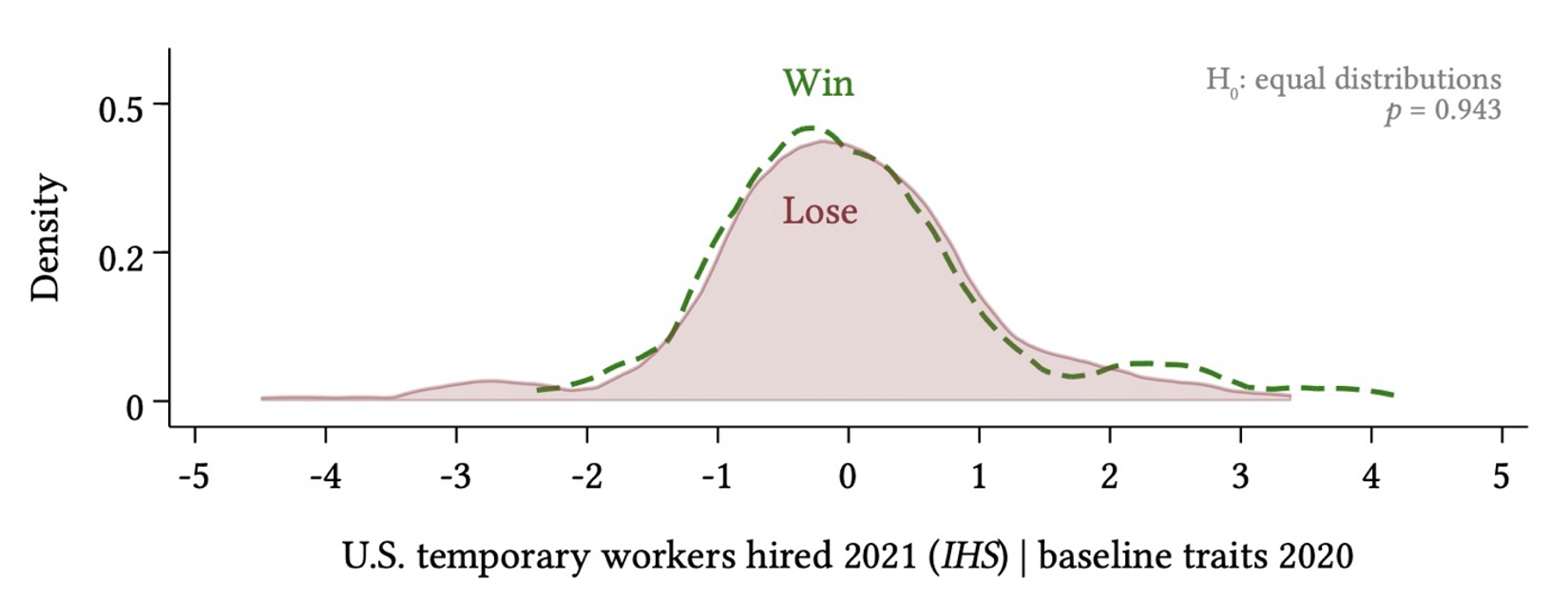

A second key finding is that firms barred at random from hiring foreigners for these jobs do not hire native workers as a replacement. The effect of losing the visa lottery on native hiring is not statistically distinguishable from zero, but if anything, losing the lottery results in fewer native hires. When otherwise identical firms are obliged to reduce foreign hiring for low-skill jobs by 50%, they reduce native hiring between zero and 5%.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of firms’ employment of US temporary workers for low-skill jobs, conditional on predetermined baseline traits. Again, the dashed green line shows ‘winning’ firms and the solid red line shows ‘losing’ firms. Though the losing firms are shifted towards hiring fewer natives, a statistical test fails to reject the equality of these distributions.

Figure 2

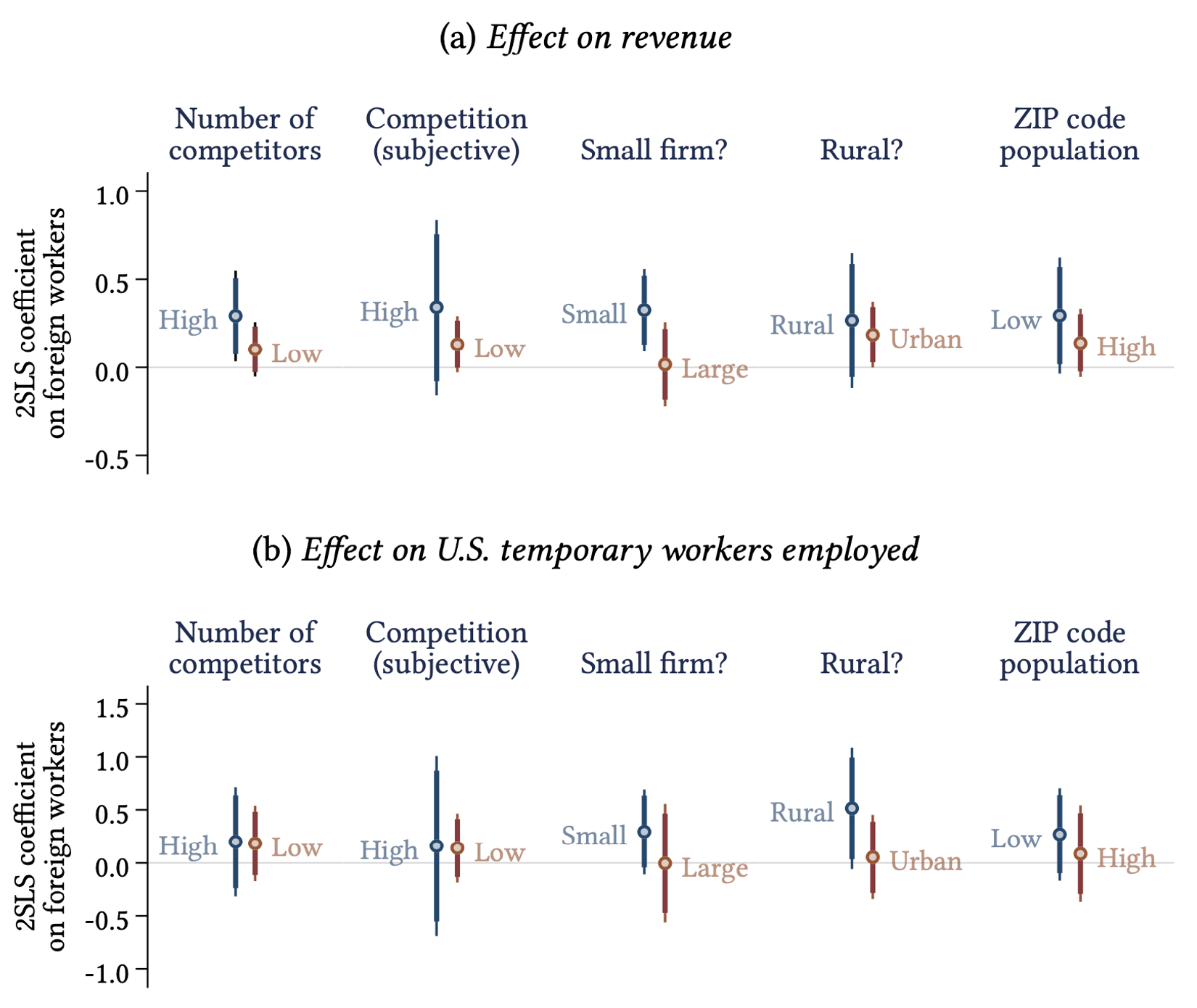

We explore prespecified tests for heterogeneous effects suggested by basic theory. Before collecting any data, we publicly posted the prediction that the lottery’s effects on revenue would be larger for firms facing greater competition. Intuitively, this is because firms facing higher price elasticity of demand (such as for a more tradeable output) could expand output relatively more in response to a positive labour supply shock without driving down the output price. We also predicted that treatment effects would be larger in rural areas, where natives – who we thought might complement scarce foreign labour – have fewer outside options for employment.

Both of those predictions are substantially confirmed in the results. The effects on revenue are consistently larger for firms facing greater competition, by two different measures. And the effects on US worker employment are much larger – and statistically distinguishable from zero at the nine percent level – in rural areas than urban areas. Figure 3 shows the prespecified tests for heterogeneity in the elasticity of each firm-level outcome to the number of foreign workers employed in low-skill jobs.

Figure 3

The overall findings of the study – that exogenous restrictions on immigrant hiring have a negative effect on production and a zero or negative effect on US hiring – are robust to all of the prespecified subgroups above. They are also robust to a battery of prespecified robustness tests, including alternative ways to measure lottery ‘success’, alternative treatment of zeros, and tests for nonresponse bias.

Interpreting the observed facts

We use this experiment to estimate a key structural parameter in a simple model of immigrant-employing firms: the native-immigrant elasticity of substitution, which has been important to the literature (e.g. Peri and Sparber 2009). The policy relevant treatment effect observed here is only compatible with very low values of the native-immigrant elasticity of substitution in firm-level production, in the range 0.8–2.1. This is substantially lower than prior estimates of this elasticity derived from different methods (such as the estimate of approximately 4 by Cortés 2008). This magnitude implies that at the policy-relevant margin, foreign and US hires in low-skill jobs are at least as different to firms as college and non-college workers.

We also use a simple forensic analysis to test and reject the hypothesis that firms respond to losing the lottery by a shift of hiring into the black market for foreign labour. Intuitively, unobserved black market hiring cannot perfectly substitute for observed immigrant hiring, because then there would be little effect of ‘losing’ the lottery on production. We show furthermore that the magnitude of the effect on production is too large to be consistent with any substantial substitution to black market labour. Thus, at the policy-relevant margin these firms are not generally not willing to hire substitute workers on the black market, something they confirm anecdotally. Indeed, if this were common, it would be challenging to explain their decision to enter a lengthy and costly process to obtain foreign workers on lawful visas.

These results have relevance to US immigration policy because they study the impact of policy change: access to the country’s principal work visa for low-skill jobs. Taken together results imply that for the policy-relevant occupations, there is simply no good substitute for foreign workers, including native workers. The results cannot be interpreted as quantifying the overall effect of immigration for low-skill jobs on national GDP, because only effects at individual firms are directly measured. However, giving firms more certainty over their ability to hire foreigners, for example through the Biden administration’s recent advance announcement of an expanded quota for 2023 (Hackman 2022), could lead to larger productivity benefits than are measured here.

References

Card, D (1990), "The impact of the Mariel boatlift on the Miami labor market", ILR Review 43(2): 245-257.

Clemens, M A, E Lewis and H Postel (2017), “The impact of immigration barriers on native workers: Evidence from the US exclusion of Mexican braceros”, VoxEU.org, 19 April.

Clemens, M A and E G Lewis (2022), “The Effect of Low-Skill Immigration Restrictions on US Firms and Workers: Evidence from a Randomized Lottery”, NBER Working Paper 30589.

Cortés, P (2008), "The effect of low-skilled immigration on US prices: evidence from CPI data", Journal of Political Economy 116(3): 381-422.

Dustmann, C, U Schönberg, and J Stuhler (2016), "The Impact of Immigration: Why Do Studies Reach Such Different Results?", Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(4): 31-56.

Edo, A, L Ragot, H Rapoport, S Sardoschau, A Steinmayr and A Sweetman (2020), “An introduction to the economics of immigration in OECD countries”, Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique 53: 1365-1403.

Hackman, M (2022), “U.S. to Issue Maximum Number of Visas Allowed for Seasonal Workers”, Wall Street Journal, 12 October.

Heckman, J J and E Vytlacil (2001), “Policy-Relevant Treatment Effects,” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 91(2): 107–111.

Mayda, A M, F Ortega, G Peri, K Shih and C Sparber (2018), “The unintended selection effects of cutting the H-1B quota”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Monras, J (2019), "Immigration and wage dynamics: Evidence from the Mexican peso crisis", VoxEU.org, 3 March.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017), The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, The National Academies Press.

Peri, G and C Sparber (2009), "Task specialization, immigration, and wages", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(3): 135-69.

Peri, G, K Shih, and C Sparber (2014), “How highly educated immigrants raise native wages”, VoxEU.org, 29 May.