The tax treatment of couples is a recurrent theme in debates about tax policy. While a majority of industrialised countries today feature some form of individual taxation (OECD 2022), many of these countries switched to individual taxation in the second half of the 20th century (e.g. Austria, Denmark, Finland, Sweden) or did so quite recently (e.g. Czech Republic, Ireland).

In addition, there are still a notable number of countries that stick to the traditional tax treatment of couples, in which the tax base is the couple’s joint income. The list of countries includes France, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, and – the focus of this column – the US. What are the rationales for changes in the tax treatment of married couples? And, given that the US did not move away from joint taxation, what were the driving forces of the reforms that took place in the US?

Levying taxes based on a couple's joint income implies that the primary and secondary earners face the same marginal tax rate. Empirical analyses have shown that this feature of the tax and transfer system is a hindrance to the labour market integration of women and can explain differential trends in the working hours of married women across countries (Bick and Fuchs-Schündeln 2017). The detrimental effect on female labour force participation has also been confirmed by Borella et al. (2023), who use a quantitative life-cycle model to show the potential welfare gain of an elimination of marriage-based taxes in the US.

The traditional tax treatment of married couples is, moreover, inconsistent with basic prescriptions of optimal tax theory. Behavioral responses to changes in the tax rate tend to be stronger for secondary earners than for primary earners. A secondary earner is, for instance, more likely to reduce hours worked or even leave the labour market than a primary earner. The inverse elasticities logic of optimal tax theory, therefore, implies that the marginal tax rate on secondary earnings should be lower than the marginal tax rate on primary earnings (e.g. Boskin and Sheshinski 1983).

In light of the arguments, it seems obvious that reforms towards individual taxation are desirable. But apparently there is something missing – an explanation for why some countries such as the US stick to the traditional tax treatment of couples? So, we seek a more detailed analysis of potential reform justifications. Are reforms towards individual taxation politically feasible? Who benefits from such reforms? Are they in the interest of secondary earners? Are they in the interest of the poor? Do they require an affirmative action rationale or can they be justified with an appeal to efficiency or other conventional notions of social welfare?

A conceptual framework for the analysis of the taxation of couples

In a recent paper (Bierbrauer et al. 2023b), we develop a toolkit that enables us to shed light on these questions.

Our framework takes the status quo tax system as given and analyses tax reforms that modify the existing tax schedule in a particular way.

Looking at reforms of the status quo has two advantages. First, the status quo tax system is the reference point in practical tax policy; reform proposals are usually described as changes of the system. Second, there were recent methodological advances in the analysis of such changes. If data on the status quo are available, one can evaluate whether the system is (1) ill-designed so that there are reforms that would make everyone better off (Bierbrauer et al. 2023a); (2) leaves room for welfare improvements (this is the case if there are reforms that make individuals better off that are, according to some criterion, deserving); and (3) can be reformed in a politically feasible way (Bierbrauer et al. 2020). Note that (1) implies (2) and (3). If (1) does not hold, any reform will produce winners and losers and this raises questions about political feasibility and desirability from a welfare perspective, possibly with conflicts between the two. In Bierbrauer et al. (2023b), we extend the methodology developed in these earlier papers so that it can be brought to the analysis of reform options in the tax treatment of married couples.

More specifically, we develop two approaches. The first approach is useful for an analysis of reforms in the traditional system of joint taxation. While such reforms alter the relevant tax functions, they do not alter the definition of the tax base: the tax base for married couples is their joint income, both before and after a reform. Consequently, the spouses in a couple both face the same marginal tax rate. The second approach is designed for reforms of the system, which drive a wedge between the marginal tax rate faced by the primary earner and the marginal tax rate faced by the secondary earner. The first approach allows us to study past reforms in the US; the second approach allows us to study reforms towards individual taxation that, so far, have not yet taken place in the US.

Past reforms in the US tax system

We analyse all reforms of the US tax system since the 1960s. Past reforms of the US tax system treated married couples and singles differently but left the alignment between primary and secondary earners’ marginal tax rates in place. We find that the differential treatment of couples and singles led to substantial changes in marriage penalties and bonuses. While some of these changes can be rationalised on efficiency grounds (e.g. a reform by the Nixon administration), others rather point to political priorities. For example, we couldn’t find an efficiency rationale for reforms by the Bush Jr. and Trump administrations.

Second, welfare analyses of past reforms in the US show the possibility of a conflict between the interests of ‘the poor’ and the interests of ‘working women’. Reforms, mostly by Republican administrations, that lowered tax rates implied a loss of tax revenue and are rejected by a Rawlsian social welfare function. At the same time, they reduced distortions in the system, and hence also the distortions faced by secondary earners. Possibly, such reforms are approved by an affirmative feminist social welfare function – one that has welfare weights that are increasing in the income share of women in the couple.

Hypothetical reforms of the tax system

We find that in the US, marginal tax rates on secondary earnings have been inefficiently high for decades: lowering marginal tax rates on secondary earnings would have been a self-financing tax reform, one that has no losers and only winners. However, there were periods, such as the mid-1980s, where marginal tax rates were too high also for primary earners. A reform in the system that lowered marginal tax rates for high-income couples would have been self-financing too. Consequently, there was no need for a reform of the system, because a reform in the system that lowered marginal tax rates for high-income couples would have been self-financing too. In the recent past, however, we find that the scope for Pareto improvements in the system has been exhausted. The only way to reap the benefits from lower taxes on secondary earnings, therefore, is a reform of the system.

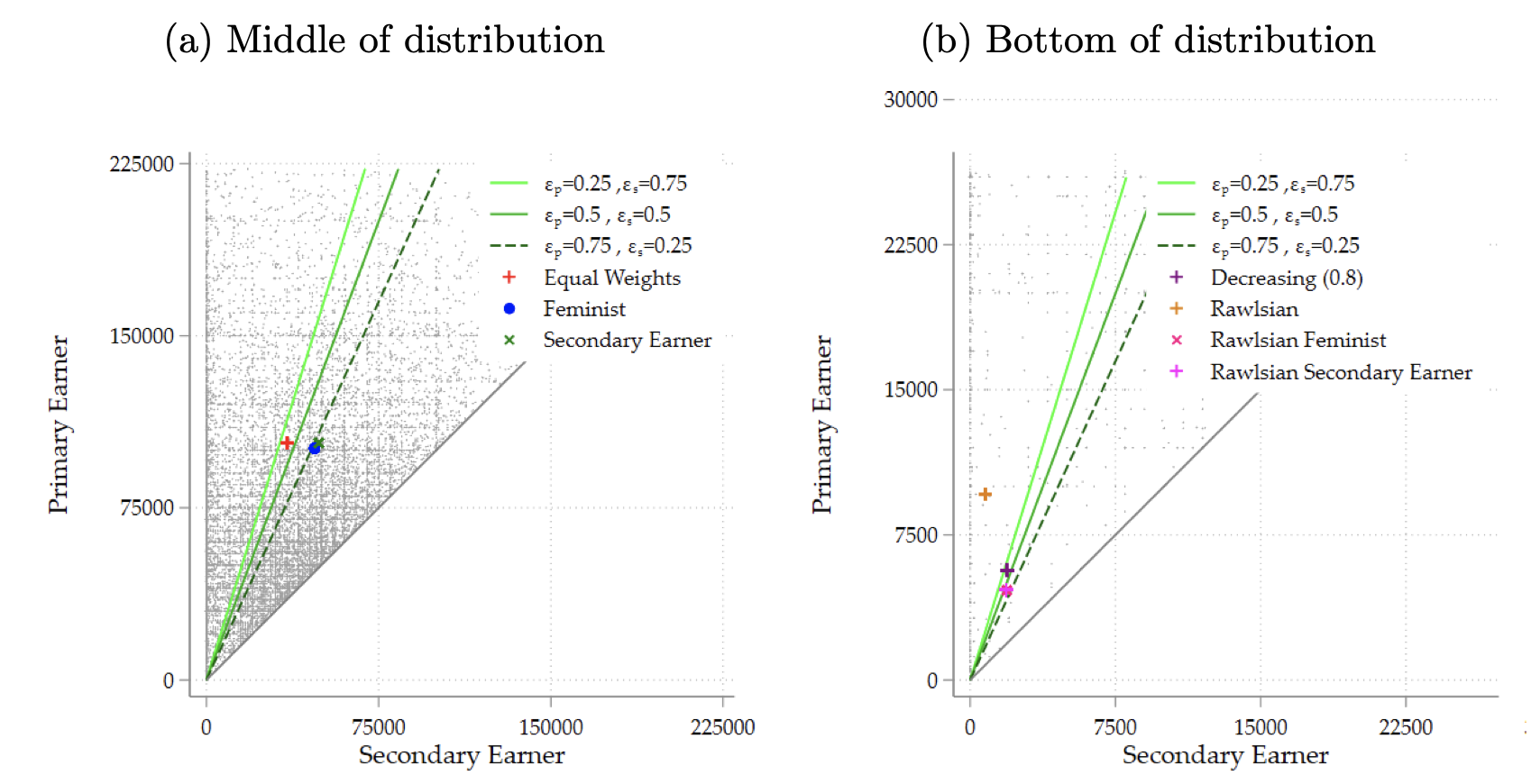

A welfare perspective on reform options

Our analysis of (hypothetical) reforms towards individual taxation – reforms that raise marginal tax rates on primary earnings and lower marginal tax rates on secondary earnings – also reveals a trade-off between the welfare of the poor and the welfare of working women. Such a reform comes with disadvantages for couples with low secondary earnings. Since the share of single-earner couples is particularly high at the bottom of the income distribution, such reform is rejected by Rawlsian social welfare functions (see Figure 1b). The beneficiaries are couples with secondary earnings close to primary earnings. Thus, such a reform increases an affirmative feminist welfare measure (see Figure 1a).

Figure 1 Reform towards individual taxation: Welfare, 2019

Notes: This figure shows for the current tax system, how a reform towards individual taxation is evaluated from a welfare perspective under different exogenous welfare weights. Figure 1a (1b) displays welfare implications for welfare weights centered in the middle (bottom) of the income distribution. Each gray dot represents a couple in the data with specific income of the primary (resp. secondary) earner displayed on the vertical (resp. horizontal) axis. Welfare evaluations with different welfare weights are plotted as a colored dot the location of which is defined via the average welfare-weighted primary earnings (vertical axis) and the average welfare-weighted secondary earnings (horizontal axis). All results are displayed including extensive margin responses. The light green solid line illustrates the result under the baseline elasticity scenario of Table 1 in which the primary (resp. secondary) earner has an elasticity of 0.25 (resp. 0.75). For illustrative purposes, the dark green solid line refers to the case where primary and secondary earners' elasticities coincide (0.5) while the dashed green line shows the results under the assumption that the primary earner's elasticity (0.75) is higher than for the secondary earner (0.25). All estimates are based on tax units with non-negative gross income in which both spouses are between 25 and 55 years old.

Source: Figure 16 in Bierbrauer et al. (2023) based on NBER TAXSIM and CPS-ASEC.

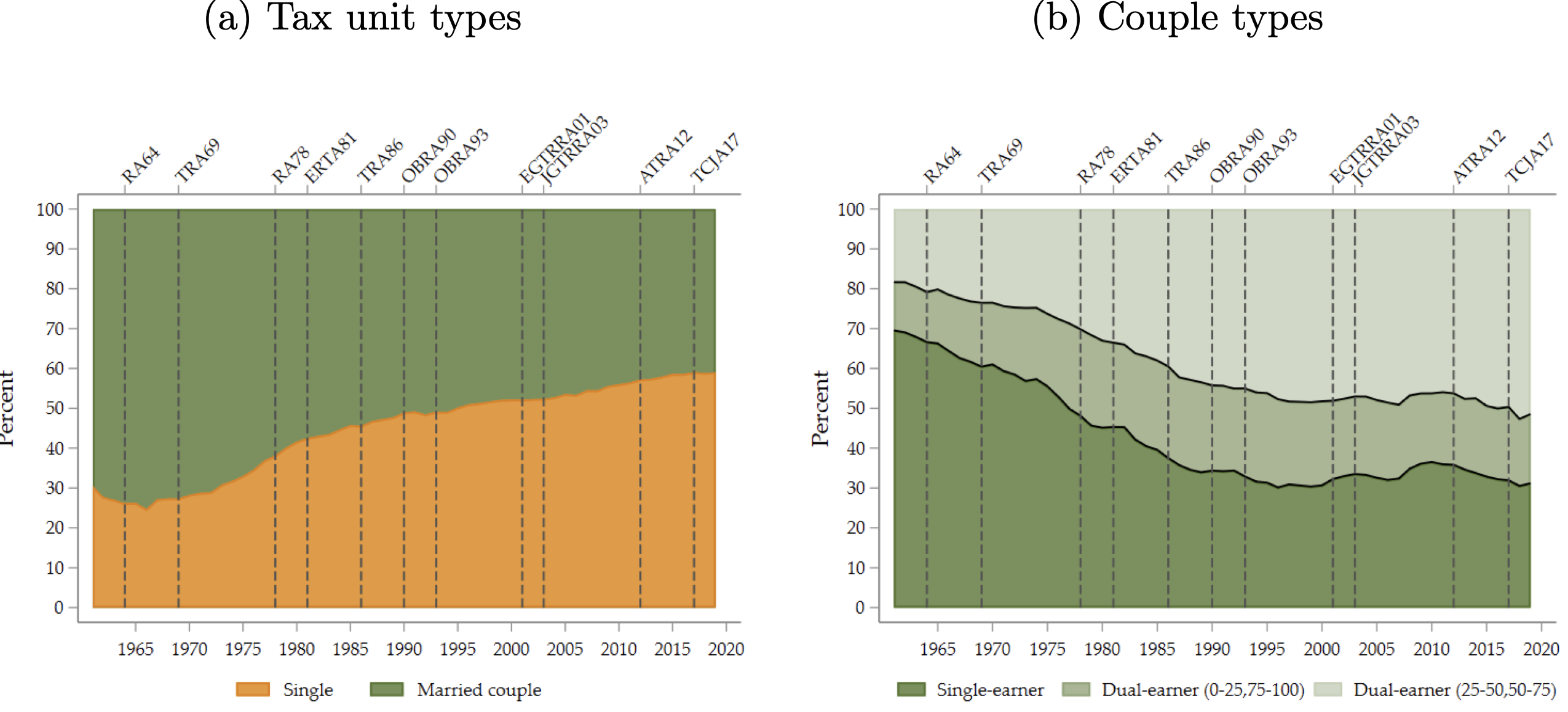

Political support for reforms towards individual taxation

Finally, we look at reforms towards individual taxation from a political economy perspective. Since the 1960s, both the share of singles relative to individuals living in married couples and the share of dual-earner couples relative to single-earner couples have been increasing (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Demographic change over time

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of tax unit types over time. Figure 4a displays the share of single tax units (orange area) and the share of couple tax units (green area). Figure 4b displays the share of single-earner and dual-earner couples. A single-earner couple refers to a married couple, in which one spouse is not employed (dark green area). The figure further displays the share of dual-earner couples in which both spouses are employed and (i) one spouse earns between 0 and 25 percent (mid green area) and (ii) between 25 and 50 percent of total earnings (light green area). Earnings shares are computed on the basis of wage, business and farm income. Reforms of the federal income tax code are displayed as vertical lines. All estimates are based on tax units with strictly positive gross income in which both spouses are between 25 and 55 years old.

Source: Figure 4 in Bierbrauer et al. (2023) based on NBER TAXSIM and CPS-ASEC.

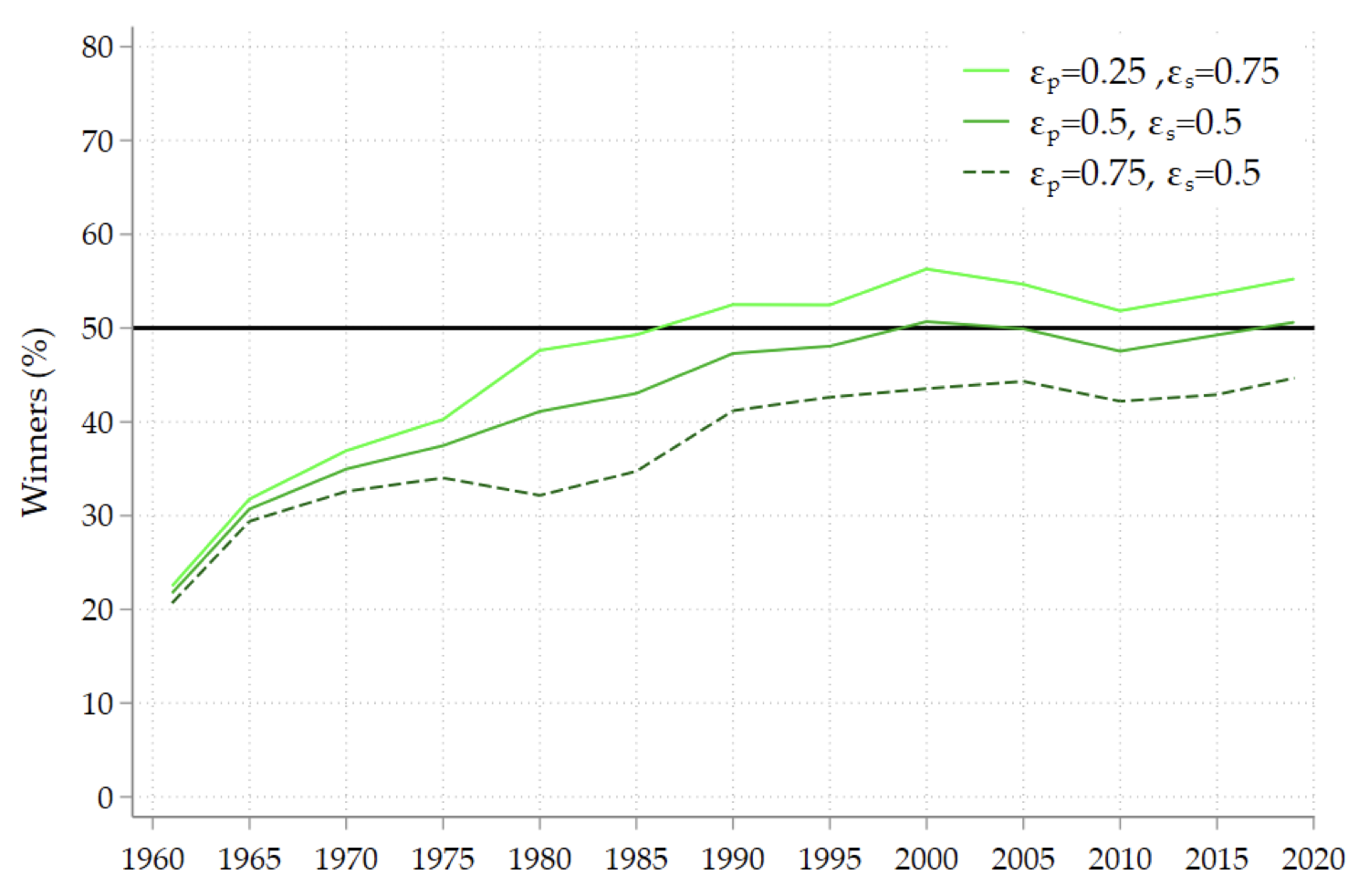

We find that in the 1960s only about a fifth of all individuals would have benefitted from a reform towards individual taxation. In the recent past, this number has risen to 50% (see Figure 3). Thus, reforms towards individual taxation are on the brink of becoming politically feasible in the US.

Figure 3 Reform towards individual taxation: Share of winners over time

Notes: This figure shows how the political support for a revenue neutral reform towards individual taxation among married couples evolved over time. All results are displayed including extensive margin responses. The light green solid line illustrates the result under the baseline elasticity scenario of Table 1 in which the primary (resp. secondary) earner has an elasticity of 0.25 (resp. 0.75). For illustrative purposes, the dark green solid line refers to the case where primary and secondary earners' elasticities coincide (0.5) while the dashed green line shows the results under the assumption that the primary earner's elasticity (0.75) is higher than for the secondary earner (0.25). All estimates are based on tax units with non-negative gross income in which both spouses are between 25 and 55 years old.

Source: Figure 15 in Bierbrauer et al. (2023) based on NBER TAXSIM and CPS-ASEC.

Towards a political economy perspective on the tax treatment of married couples

There is a rich literature on the political economy of taxation. A key question in this literature is how changes in inequality transmit via the political process into changes in redistributive taxation. (This literature is discussed in more detail in Bierbrauer et al. 2020). To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous work that looks at the taxation of couples from a political economy perspective. We take first steps in that we look at what the changes of inequality between men and women since the 1960s imply for the political feasibility of reforms towards individual taxation. A key finding is that such reforms lacked majority support in the past. As of today majority support is no longer lacking. So, it will be interesting to see what will happen to the tax treatment of married couples and singles in the near future.

References

Bick, A and N Fuchs-Schündeln (2017), “Taxation and Labour Supply of Married Couples across Countries: A Macroeconomic Analysis”, Review of Economic Studies 85(3): 1543-1576.

Bick, A, B Brüggemann, N Fuchs-Schündeln, and H Paule-Paludkiewicz (2018), “Taxation and the labour supply of married couples: Evidence from the US and Europe since the 1980s”, VoxEU.org, 15 November.

Bierbrauer, F J, P C Boyer, and A Peichl (2020), “Towards politically feasible and welfare-improving tax reforms”, VoxEU.org, 07 October.

Bierbrauer, F J, P C Boyer, and E Hansen (2023a), “Pareto-improving tax reforms and the Earned Income Tax Credit”, Econometrica 91(3).

Bierbrauer, F J, P C Boyer, A Peichl and D Weishaar (2023b), “The taxation of couples”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18138.

Borella, M, M De Nardi, and F Yang (2019), “Marriage-related taxes and Social Security benefits are holding back women’s labour supply in the US”, VoxEU.org, 23 November.

Borella, M, M De Nardi, and F Yang (2023), “Are Marriage-Related Taxes and Social Security Benefits Holding Back Female Labour Supply?”, Review of Economic Studies 90(1): 102-131.

Boskin, M J and E Sheshinski (1983), “Optimal tax treatment of the family: Married couples”, Journal of Public Economics 20(3): 281-297.

Golosov, M and I Krasikov (2023), “The Optimal Taxation of Couples”, NBER Working Paper 31140.

Kleven, H J, C T Kreiner and E Saez (2009), “The Optimal Income Taxation of Couples”, Econometrica 77(2): 537-560.

OECD (2022), Tax Policy and Gender Equality: A Stocktake of Country Approaches, OECD Publishing.