Claudia Goldin was recently awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics for her ground-breaking work in understanding gender disparities in the labour market (Boustan and Kuziemko 2023). Among her numerous influential contributions, she describes the ‘quiet revolution’ (Goldin, 2006), which wasn't just about the massive entry of American women into the labour market but about how, since the late 1970s, the nature of their participation underwent a significant transformation: the traditional role of secondary workers has evolved into the pursuit of professional careers.

While Latin America experienced this transformation with some delay compared to more developed regions, it has seen remarkable progress in women's advancement and the convergence of gender roles. According to GenLAC (CEDLAS, 2022), today, 67% of women in the region actively participate in the labour market, with roughly half of them occupying professional and technical positions. However, despite these encouraging developments, substantial gender disparities persist in Latin American labour markets. Men are significantly more involved in the labour force, surpassing women by 27 percentage points, with monthly earnings 17% higher than women with similar qualifications and holding over 60% of managerial positions (Marchionni et al. 2019).

But this ‘quiet revolution’ has not been paralleled with an equivalent shift in gender roles, presenting women with the additional obstacle of balancing family and work. In fact, when faced with the immense challenge of parenthood, it is women who adjust their roles in the labour market to support child-rearing (Bertrand et al. 2010). Therefore, motherhood appears as one of the key factors behind the remaining gender gaps in the labour market.

Recent literature has focused on measuring the impact of motherhood using an event study approach around the birth of the first child. In developed countries, the evidence is clear and pervasive: the arrival of children has been shown to have negative, substantial, and long-lasting effects on mothers’ labour outcomes, but not on fathers’ (Kleven et al. 2019a, 2019b, Kuziemko et al. 2018, Washington et al. 2018). Following the birth of the first child, women often reduce their labour force participation and working hours, leading to a decrease in their earnings. Importantly, these effects do not reverse over time, resulting in persistent long-term labour market gaps between fathers and mothers following the birth of the first child.

These effects stemming from motherhood are closely intertwined with the demand for time flexibility to manage both work and family responsibilities. Indeed, Goldin has shown that the wage penalty is intricately connected to this issue. She argues that high-paying positions often lack flexibility, posing challenges in balancing work and childcare responsibilities, a burden that societal norms primarily place on women. Therefore, she suggests that the solution to bridging gender gaps lies in reshaping job structures and compensation schemes to discourage the rewarding of extended working hours or rigid schedules (Goldin 2014).

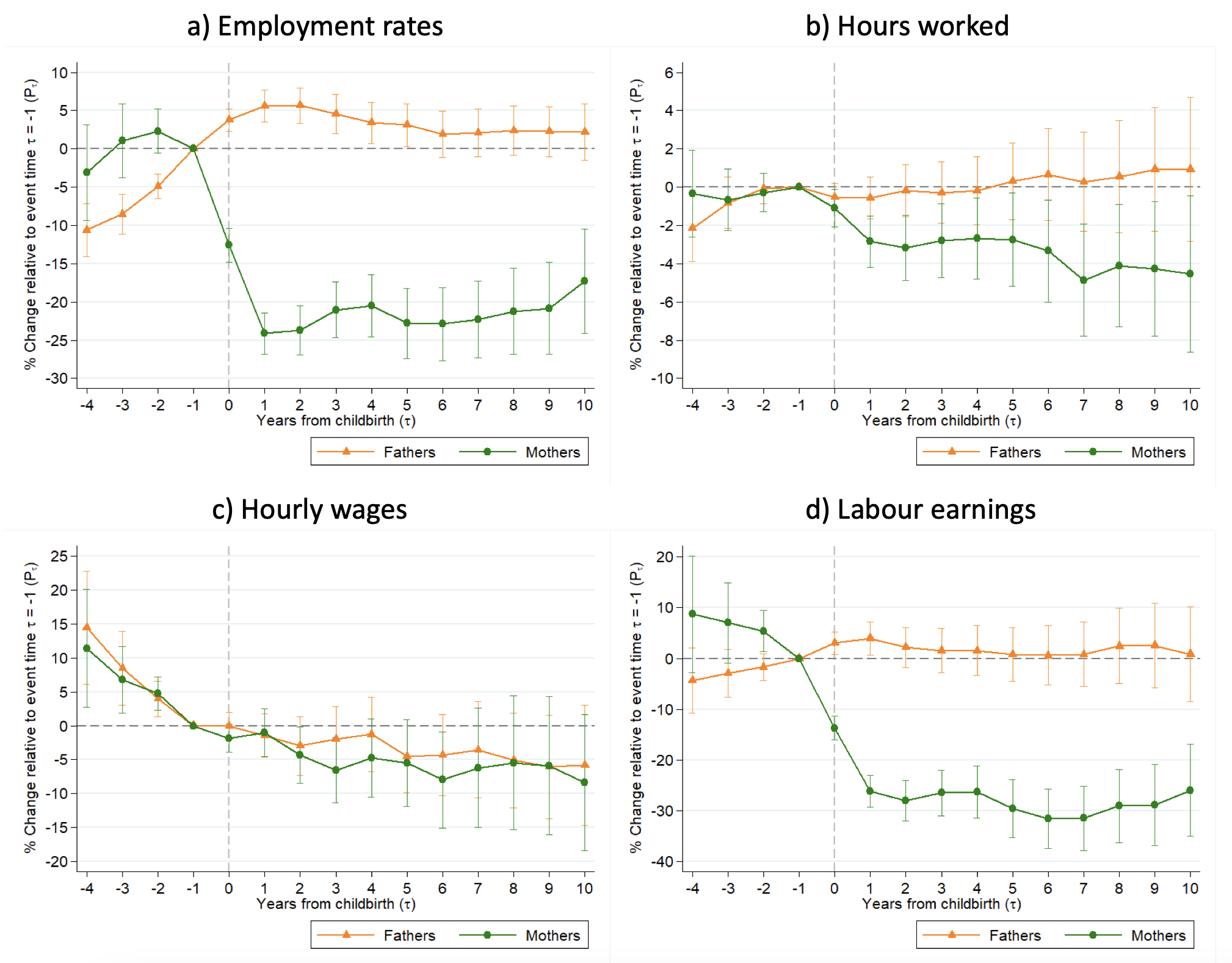

In a joint work with Lucila Berniell and Dolores de la Mata (Berniell et al. 2021), we delved into the impact of motherhood in a developing country – Chile. Unsurprisingly, we found that, much like in developed nations, the birth of a first child leads to a large and enduring negative impact on mothers’ labour outcomes. Upon motherhood, female employment declines by 22%, hours worked reduce by 4%, and labour earnings decrease by 28% (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Parenthood effects on labour supply and labour earnings in Chile

Notes: The figure shows the percentage change on labor outcomes following the first childbirth, relative to the year preceding the birth.

Source: Berniell et al. (2021).

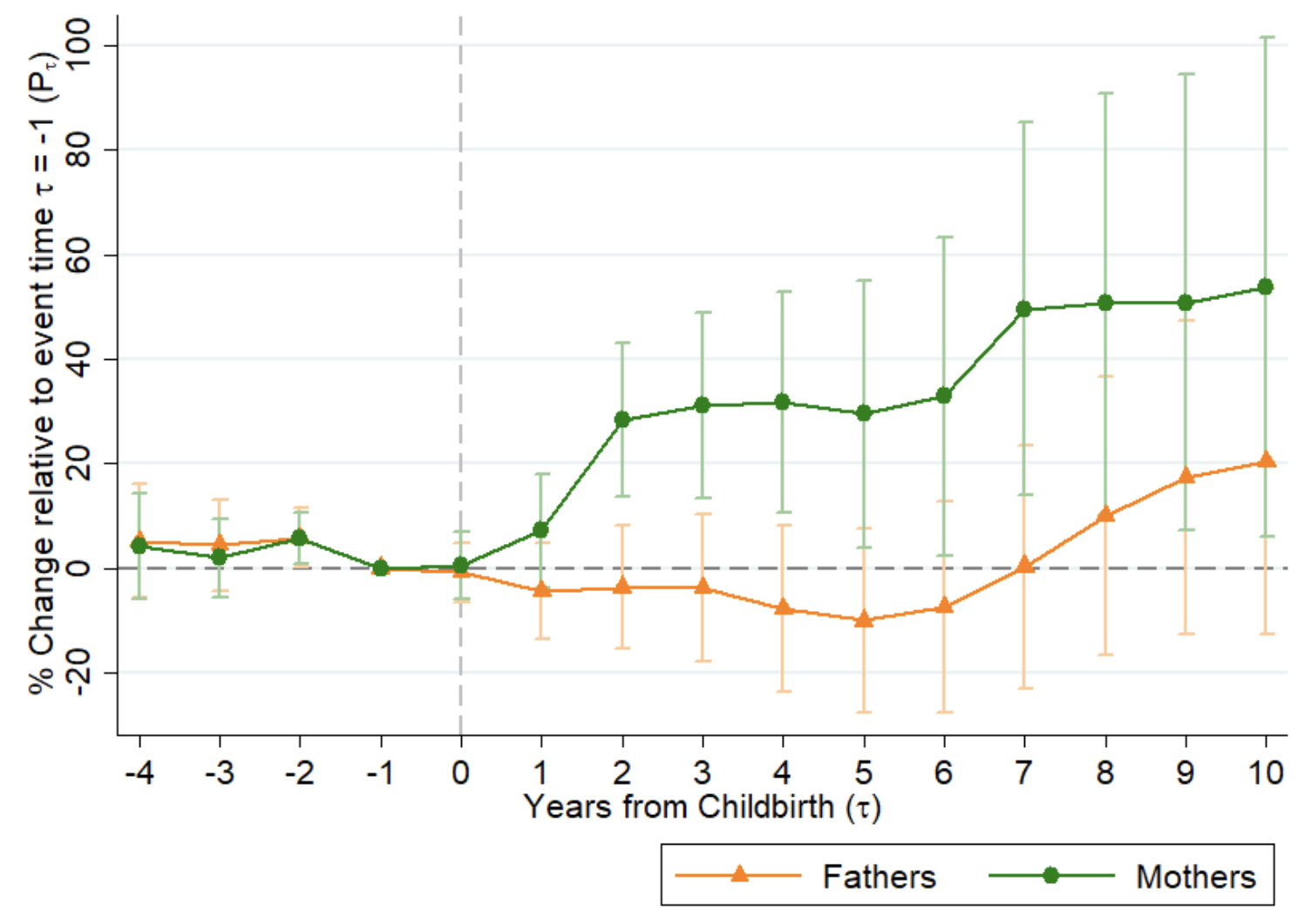

In contrast, we find that even though motherhood effects in a developing country such as Chile do not differ much from those in the developed world, the demand for flexibility materialises in a different way. The evidence for Chile is the first to reveal that, in developing countries, the demand for labour flexibility is giving rise to a segmentation between good-quality (formal) and bad-quality (informal) employment opportunities for women. Indeed, we find that in Chile, the birth of the first child rises the probability of securing an informal job by 38% for mothers, and not for fathers (see Figure 2). We argue that this is the result of a demand for flexibility of mothers, given that the Chilean formal labour market predominantly comprises full-time positions, with part-time or more flexible opportunities being very rare. Opting for flexibility through informal jobs imposes significant burdens on women, as informal positions entail reduced social benefits, lower pay compared to formal employment, and limited future professional prospects.

Figure 2 Parenthood effect on labour informality in Chile conditional on being employed

Notes: The figure shows the percentage change in the labour informality rate (conditional on working) following the first childbirth, relative to the year preceding the birth.

Source: Berniell et al. (2021)

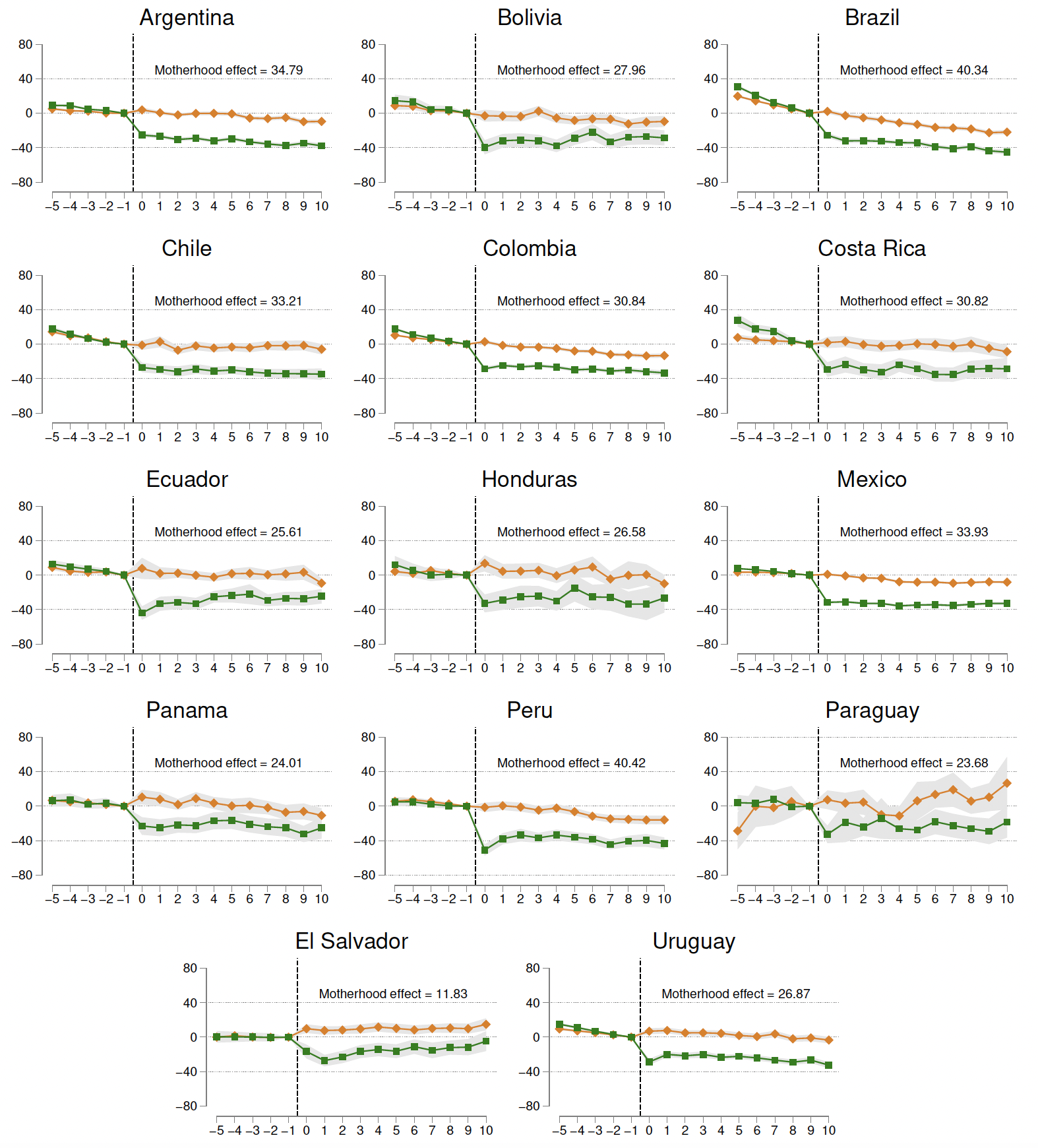

Of course, Chile is no exception. In Berniell et al. (2023), we show similar patterns in Peru, Mexico, and Uruguay. More recently, Marchionni and Pedrazzi (2023) have extensively documented the effects of motherhood throughout Latin America. Once again, they employ an event study approach, but this time, relying on pseudo-panels (Kleven et al. 2022) constructed from cross-sectional data from household surveys spanning the past two decades. This approach allows painting a comprehensive picture for the entire region, using comparable data and methodology.

They document that, upon motherhood, women's employment decreases in all countries accompanied by an increase in part-time and informal employment among mothers. Collectively, these factors account for the substantial decline in women's income after becoming mothers (see Figure 3). On average, across the region, the motherhood effect on earnings amounts to a 35% reduction.

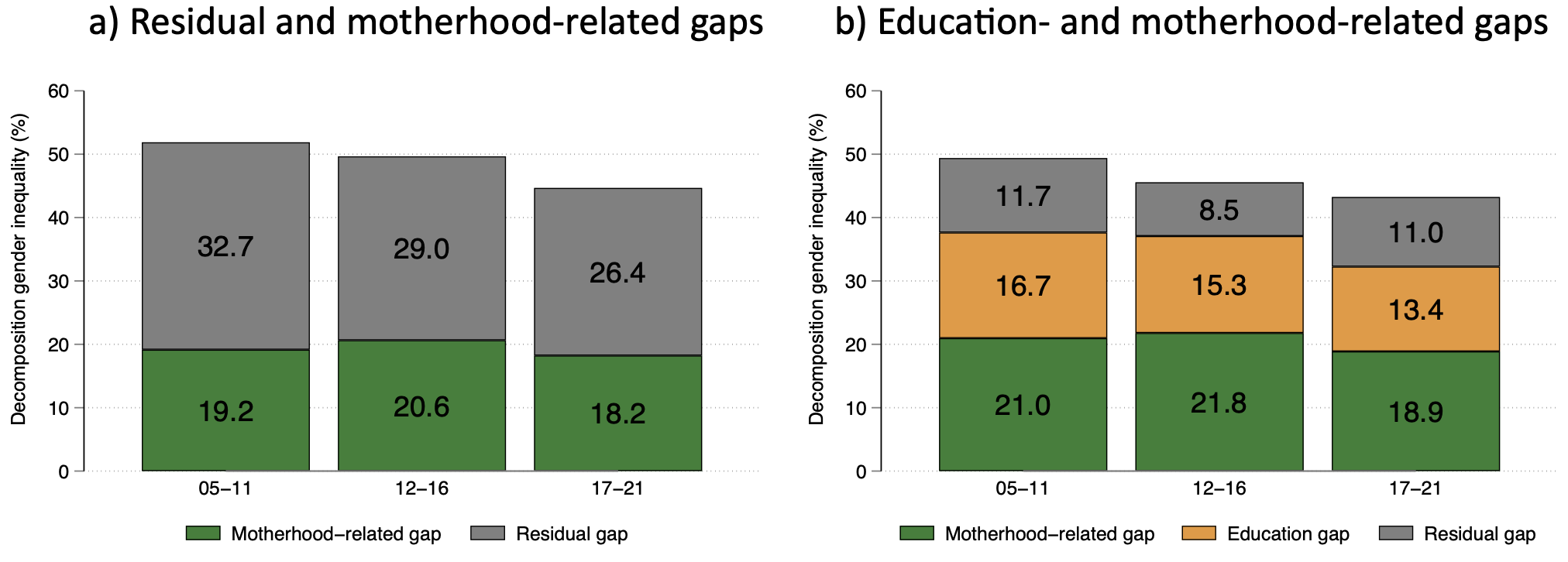

Moreover, they show that the primary factor contributing to the persistent income inequality between men and women in Latin America is the negative impact of motherhood on earnings. While the overall gender gap in earnings has narrowed by seven percentage points over the last two decades – decreasing from 51.9% to 44.6% – the gap attributed to children has remained virtually unchanged. Over time, the motherhood-related gap as a share of the total gender gap has increased from 37% to 41% (see Figure 4). Furthermore, the contribution of motherhood to gender inequality demonstrates a higher degree of inflexibility, compared to other sources of inequality such as education and its returns.

Figure 3 Parenthood effect on labour earnings across Latin American countries

Notes: The figure shows the percentage change in monthly labour earnings for mothers (green) and fathers (orange) across all countries following the first childbirth, relative to the year preceding the birth.

Source: Marchionni and Pedrazzi (2023).

Figure 4 Decomposition of the gender gap in earnings, 14 Latin American countries, 2005-2021

Notes: The figure shows the percentage points by which the motherhood related gap and other sources (e.g. the gender gap in education levels and returns) contributes to the overall gender earnings gap.

Source: Marchionni and Pedrazzi (2023).

These issues require our collective attention and policy-driven solutions. To achieve true gender equality, we must address the challenges associated with women's participation in the labour market, which are deeply intertwined with gender roles and caregiving responsibilities. The barriers hindering women's full integration into the labour market are pervasive throughout society and are predominantly rooted within the household.

Editors' note: This column is published in collaboration with the International Economic Associations’ Women in Leadership in Economics initiative, which aims to enhance the role of women in economics through research, building partnerships, and amplifying voices.

References

Berniell, I, L Berniell, D De la Mata, M Edo and M Marchionni (2021), “Gender gaps in labor informality: The motherhood effect”, Journal of Development Economics 150: 102599.

Berniell, I, L Berniell, D De la Mata, M Edo and M Marchionni (2023), “Motherhood and flexible jobs: Evidence from Latin American countries”, World Development 167: 106225.

Bertrand, M, C Goldin and L F Katz (2010), “Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2(3): 228-255.

Boustan, L and Kuziemko (2023), “Claudia Goldin, Nobel laureate: Gender gaps and the broader agenda on inequality”, VoxEU.org, 24 October.

CEDLAS (2022), GenLAC – Evidence for gender equity in Latin America and the Caribbean (Version 2.1) (database).

Goldin, C (2006), “The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women's Employment, Education, and Family”, American Economic Review 96(2): 1–21

Goldin, C (2014), “A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter”, American Economic Review 104(4): 1091-1119.

Kleven, H (2022), “The geography of child penalties and gender norms: Evidence from the United States”, NBER Working Paper No. 30176.

Kleven, H, C Landais, J Posch, A Steinhauer and J Zweimuller (2019a), “Child penalties across countries: Evidence and explanations”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 109: 122–26.

Kleven, H, C Landais and J E Søgaard (2019b), “Children and gender inequality: Evidence from Denmark”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(4):181–209.

Kuziemko, I, J Pan, J Shen and E Washington, E. (2018), “The mommy effect: Do women anticipate the employment effects of motherhood?”, NBER Working Paper No. 24740.

Marchionni, M, L Gasparini and M Edo (2019), Brechas de género en américa latina. Un estado de situación, CAF Development Bank of Latinamerica No. 1401.

Marchionni, M and J Pedrazzi (2023), “The Last Hurdle? Unyielding Motherhood Effects in the Context of Declining Gender Inequality in Latin America”, CEDLAS Working Paper No. 321.

Washington, E, J Pan, J Shen and L Kuziemko (2018), “Women's anticipation of the employment effects of motherhood: Evidence and implications”, VoxEU.org, 22 September.