The rise of giant companies and the fall in labour share in national income in several countries have renewed the interest of economists in the consequences of the imbalance of power between workers and firms, leading to monopsonistic labour markets. The main idea behind monopsony is that the labour supply curve to an individual firm is not infinitely elastic, i.e. an employer that cuts wages by a given amount may find it somewhat harder to recruit and retain workers, but would not immediately lose all its employees to competitor firms, as is predicted to happen in perfectly competitive labour markets. As a result, employers are incentivised to mark down the wages of workers. Limited labour supply elasticity may derive from a combination of workers’ imperfect knowledge of their outside options, their limited mobility, or their idiosyncratic preferences over non-wage job attributes (Manning 2021).

In a dynamic labour market, employer market power is jointly determined by the entry and exit margins of labour supply, measuring to what extent higher wages ease recruitment and reduce quits, respectively. There is a large and growing body of work estimating the elasticity of separations to wages (Sokolova and Sorensen 2021), but evidence on the recruitment margin is more limited. There is some evidence of the elasticity of job applicants to wages (Kircher et al. 2018), but it is unclear how strongly this corresponds to firms filling vacancies faster. In a recent paper (Bassier et al. 2023) we investigate the extent to which higher-wage firms can fill job vacancies faster, making recruitment easier. Besides its relationship to market power, the study of the determinants of vacancy duration is interesting in its own right, to complement the vast existing evidence on the process of worker search with corresponding evidence on search duration on the employer side.

Our research uses data on the near-universe of online job adverts in the UK, containing high-frequency information on the stock of vacancies and detailed job characteristics, including the wage offered. The correlation between the number of weeks a vacancy remains posted (i.e. unfilled) and the wage offered on the advert implies an elasticity of -0.2, i.e. that a 10% increase in the wage is associated with a reduction of about 2% in the vacancy duration – a minor effect. However, this result is contaminated by unobservable job characteristics, as highly skilled jobs on average pay higher wages and at the same time require longer search processes; this misleadingly shrinks the association between wages and vacancy duration (Faberman and Menzio 2018, Amior 2019). Indeed, if one compares subsequent adverts for the same job, a 10% increase in the wage is associated with a larger reduction of about 4% in the vacancy duration – still a small impact.

An additional confounding factor is represented by reverse causality: for example, firms may strategically decide to post higher wages on a certain job if they expect it to be harder to fill, for example, because there are many similar job postings in the labour market, or because competing firms are posting higher wages. This mechanism would bias the elasticity of vacancy duration towards zero (or would make it positive if reverse causality is especially strong) because we would observe firms increasing wages with little apparent change in vacancy durations.

To address this challenge, we exploit sharp and plausibly exogenous firm-level changes in wages, implying that a firm's job vacancies will be most competitive just after a discrete wage adjustment and least competitive just before, against a backdrop of constant or slowly evolving labour market conditions. To implement this strategy, we leverage common firm-level practices to revise wages at regular intervals (in most cases annually), leading to wage upratings that are typically sizable and apply across all jobs in a firm, independent of hiring difficulties in any specific job. Hence the timing and magnitude of a wage policy are unlikely to be influenced by contemporaneous shocks to hiring difficulties on a given job.

Our research follows two complementary approaches, based on what can be defined as ‘external’ and ‘internal’ measures of wage adjustments, respectively. The external measure imports information on pay settlements surveyed by an independent body that collects data on collective agreements. The internal measure infers wage-setting events from information on wages posted on job adverts, by isolating weeks in which there is a discrete wage change, surrounded by weeks without wage changes. For both approaches, we estimate how vacancy durations within each specific job title in the firm change before versus after the relevant firm wage adjustment. We net out changes in nearby firms at the same time, to make sure the estimate is not biased by broader labour market events.

Based on the external measure of wage adjustments, we estimate a much higher response of vacancy duration to wage changes, with an elasticity of -4.8. When using the internal measure, we estimate a very similar elasticity of around -4.3. Although the external and internal definitions of wage changes are based on different sources of information and have different strengths and weaknesses, we find that estimates that exploit each source of variation yield closely comparable results.

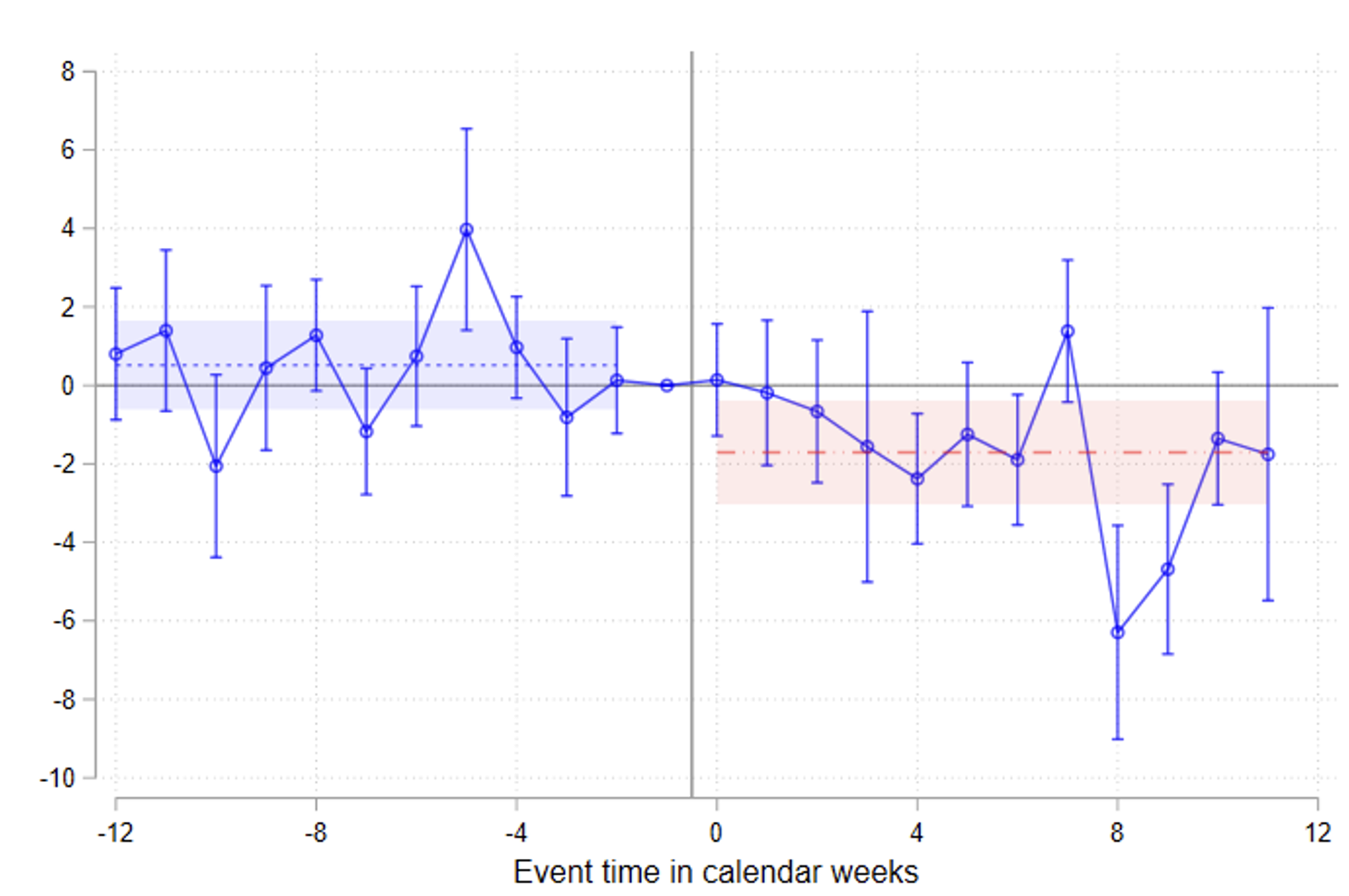

Given the richness and high frequency of the job advert data, we further investigate the dynamic effects of discrete wage changes, to shed light on the speed of labour market adjustment to a change in relative wages. Figure 1 plots the duration elasticity of a vacancy posted at time t, with respect to the wage change that has taken place at time zero. The estimates are close to zero before the wage-change event (only one of them is statistically different from zero), suggesting that these large firm-level wage increases are not systematically related to prior dynamics in vacancy durations. The average post-event coefficient is instead negative and significant. The dynamic pattern is noisy but is suggestive of some initial delay in the response of vacancy duration to wage changes.

Figure 1 Dynamic effects of a wage increase on the duration of job vacancies

Source: Authors’ calculations on data from online job adverts in the UK, 2017-2019 (Adzuna)

The research additionally shows that the response of vacancy duration to wages is heterogeneous along a few interesting dimensions. First, duration elasticities are larger for vacancies posted by recruitment agencies than for those posted by direct employers. This possibly suggests that workers may more easily compare wages on similar jobs on agencies' websites, making search behaviour more sensitive to wage differences. This is an important, previously undetected, aspect of heterogeneity, given the rising importance of recruitment agencies. Second, the magnitude of the duration-wage elasticity is higher for tight labour markets, with above-median vacancy rates, than in labour markets with below-median rates. As one would expect, slacker markets are less competitive, as workers have fewer outside options, and their search strategies are not as responsive to higher wages as they would be in a more competitive labour market.

Overall, our estimates of the response of vacancy durations to wages help us understand the entry margin of employer market power, which complements the large existing literature on the exit margin. While our estimates suggest slightly more responsiveness on this entry margin, they reinforce the relevance of monopsonistic labour markets and the associated ability of firms to mark down the wages of workers.

References

Amior, M (2019), “Education and Geographical Mobility: The Role of the Job Surplus”, Discussion Paper 1616, Centre for Economic Performance.

Bassier, I, A Dube and S Naidu (2022), “Monopsony in Movers: The Elasticity of Labor Supply to Firm Wage Policies”, Journal of Human Resources 57: S50–S86

Bassier, I, A Manning and B Petrongolo (2023), “Vacancy duration and wages”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18365.

Belot, M, P Kircher and P Muller (2018), “Job Seeker responses to wages in adverts”, VoxEU.org, 22 December.

Faberman, J and G Menzio (2018), “Evidence on the Relationship between Recruiting and the Starting Wage”, Labour Economics 50: 67–79.

Manning, A (2021), “Monopsony in Labor Markets: A Review”, ILR Review 74(1): 3–26.

Sokolova, A and T Sorensen (2021), “Monopsony in labor markets: A meta-analysis”, ILR Review 74(1): 27–55.