The EU economy has outperformed expectations, buoyed by a strong labour market and tumbling gas prices

The EU economy has weathered the adversities of the past three years remarkably well. A challenging post-pandemic adjustment , the energy crisis, renewed disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine, and synchronised global tightening of monetary conditions (Dieppe and Brignone 2022) all presaged a winter recession in the EU (Hoffman et al. 2022). Instead, the smaller-than-projected contraction in the last quarter of last year and even a small rebound of growth in the first quarter of this year dispelled the spectre of a winter recession. Key factors underpinning the better-than-expected performance are the continued employment growth and sharply declining energy prices, offsetting the drag of further monetary tightening. The European Commission Spring 2023 Forecast (European Commission 2023a) lifts the growth projections for the EU economy to 1.0% in 2023 and 1.7% in 2024 (from 0.8% and 1.6% in 2023 and 2024, respectively. in the Winter Interim Forecast), virtually closing the gap with potential output by the end of the forecast horizon.

Thanks to diversification of supply, investments to address supply bottlenecks, boosts to production of renewable energy, and a sizeable reduction in gas consumption, the EU has managed to wean itself off Russian fossil fuels. As the EU approaches the gas-refilling season, gas storage levels are at comfortable levels and risks of shortages during next winter have considerably abated. The sharp deterioration of terms of trade in 2021 and 2022, as energy (imported) prices surged, resulted in a transfer of purchasing power from the EU to the rest of the world. With energy prices rapidly falling, the expected improvement in terms of trade over the forecast horizon will drive a reversal of this effect, to the benefit of all domestic sectors of the economy – households, corporates, and governments.

The record-strong labour market has been a key element underpinning the resilience of the EU economy. The unemployment rate hit a new record low, at 6.0% in March 2023, with participation and employment rates at record highs. Going forward, the EU labour market is expected to react only mildly to the slower pace of economic expansion. Employment growth is forecast to slow down, but the unemployment rate is expected to remain just above 6%. More sustained wage increases are expected on the back of persistent tightness of labour markets, strong increases in minimum wages in several countries and, more generally, workers’ claims to recoup purchasing power.

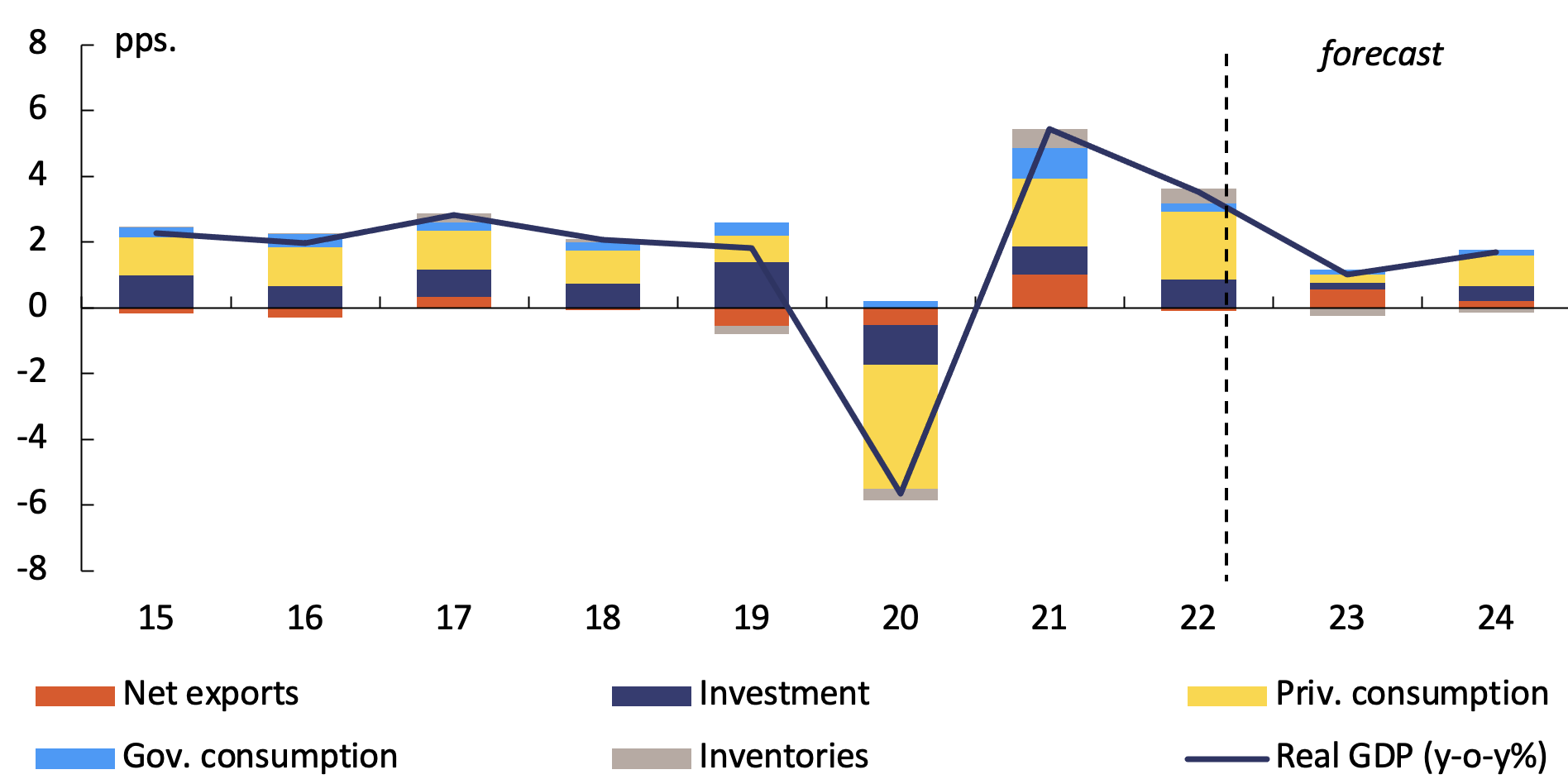

Figure 1 Contributions to EU GDP growth

Source: Spring 2023 Commission Forecast

Inflationary pressures have proved more persistent, setting monetary authorities on a path of further tightening

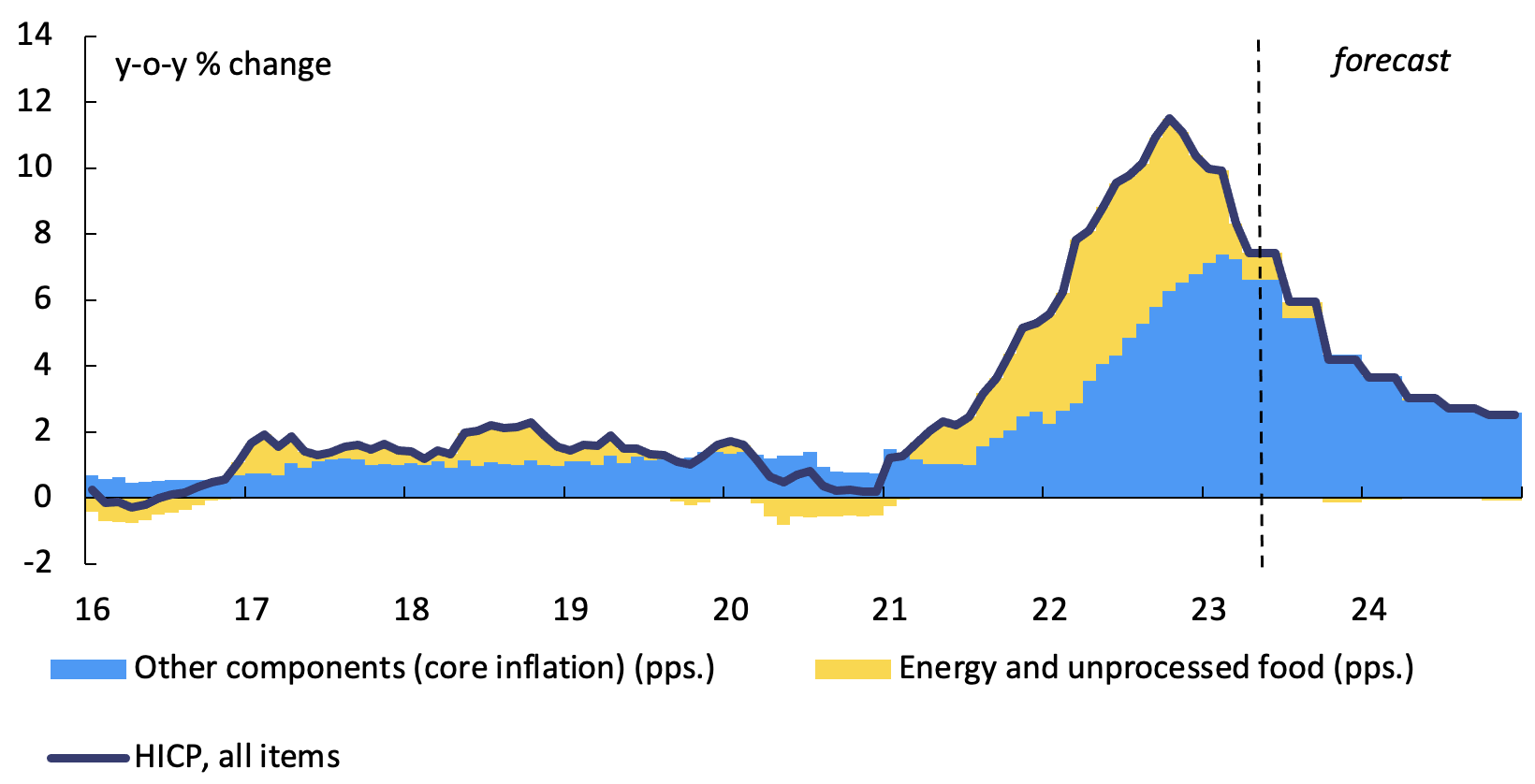

Falling energy commodity prices are driving a sharp fall in energy bills, but core inflation (that is, headline inflation net of energy and unprocessed food) has been firming, on the back of a delayed pass-through of higher energy costs and generally input prices, but also resilience of domestic demand. The small contraction of core inflation in April suggests that – as projected in the forecast – core inflation might by now also have peaked. Still, returning towards the ECB’s inflation target is expected to take longer. Persisting core price pressures have led the Spring Forecast to lift the outlook for inflation to 5.8% in 2023 and 2.8% in 2024 in the euro area.

Figure 2 Inflation outlook, euro area

Source: European Commission (2023a)

In response to persistent core inflation, the ECB and other EU central banks are expected to tighten monetary conditions more forcefully. In its meeting of 5 May, the ECB Governing Board lifted policy rates by 25 basis points, down from 50 basis points in the previous two rounds of policy hikes. At the cut-off date of the Spring Forecast, the euro area short-term rate was expected to peak at 3.8% in 2023-Q3, before abating in the course of 2024. According to market excitations, the end of the monetary tightening cycle is now in sight, but future rates could again be reviewed higher, if core inflation becomes more persistent.

Deficit- and debt-to-GDP ratios are on a decreasing path, but persistently high inflation would increase risks to debt sustainability

A period of high inflation can help improve the general government balance in the short term, as tax revenues generally react immediately, while expenditure adjust with a delay (ECB 2023, IMF 2023: Chapter 2).

However, the impact is likely to be less favourable when the inflation is driven by an adverse terms of trade shock, such as a rapid increase in imported energy prices. Shocks of this nature not only weigh on potential growth, but can also prompt governments to introduce support measures to partly compensate households and firms for higher energy costs.

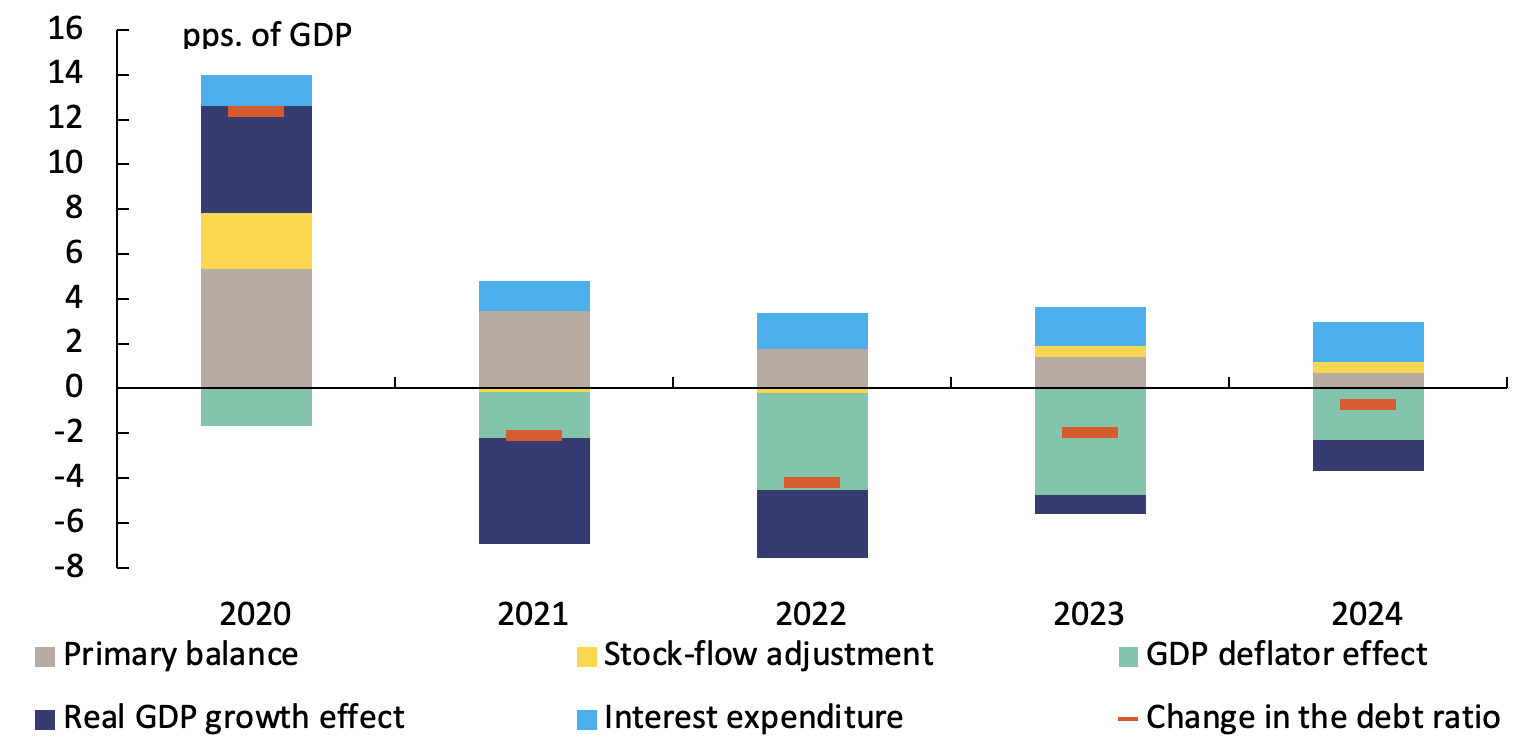

Both effects have in fact weighed on general government balances. Still, high inflation and strong real GDP growth, coupled with the unwinding of pandemic-related emergency measures, are set to dominate in the short term, leading to a reduction of the aggregate EU government deficit to 3.4% of GDP in 2022. In 2023 and (especially) in 2024, the expected phasing out of energy support measures is forecast to further drive deficit reduction, to 3.1% and 2.4% of GDP, respectively. High inflation (via the GDP deflator) has also contributed to an overall reduction in debt-to-GDP ratios in the EU in 2022 and is forecast to do so again in 2023 and 2024 (Figure 3), despite energy support measures and increased debt financing costs. The EU debt-to-GDP ratio fell to around 85% of GDP in 2022, from a record high of 92% in 2020. It is projected to further decline to below 83% of GDP in 2024. The reduction in the debt ratio is expected to be particularly pronounced for high-debt member states with a primary budgetary surplus (i.e. Cyprus, Greece, and Portugal).

Over time, however, monetary policy tightening will feed into higher costs of servicing public debts, with a greater impact on those member states with higher debt ratios. Large expenditure items like pensions and other social transfers, as well as public wages, are also set to progressively adjust to the higher price level. This will increase risks to debt sustainability in the EU and calls for prudent fiscal policies on the part of member states to put high debt ratios on a steadily declining path in the medium term.

Figure 3 Drivers of the change in the EU debt-to-GDP ratio

Source: Spring 2023 Commission Forecast

Fiscal space created by the reversal of energy measures should be used to reduce deficits…

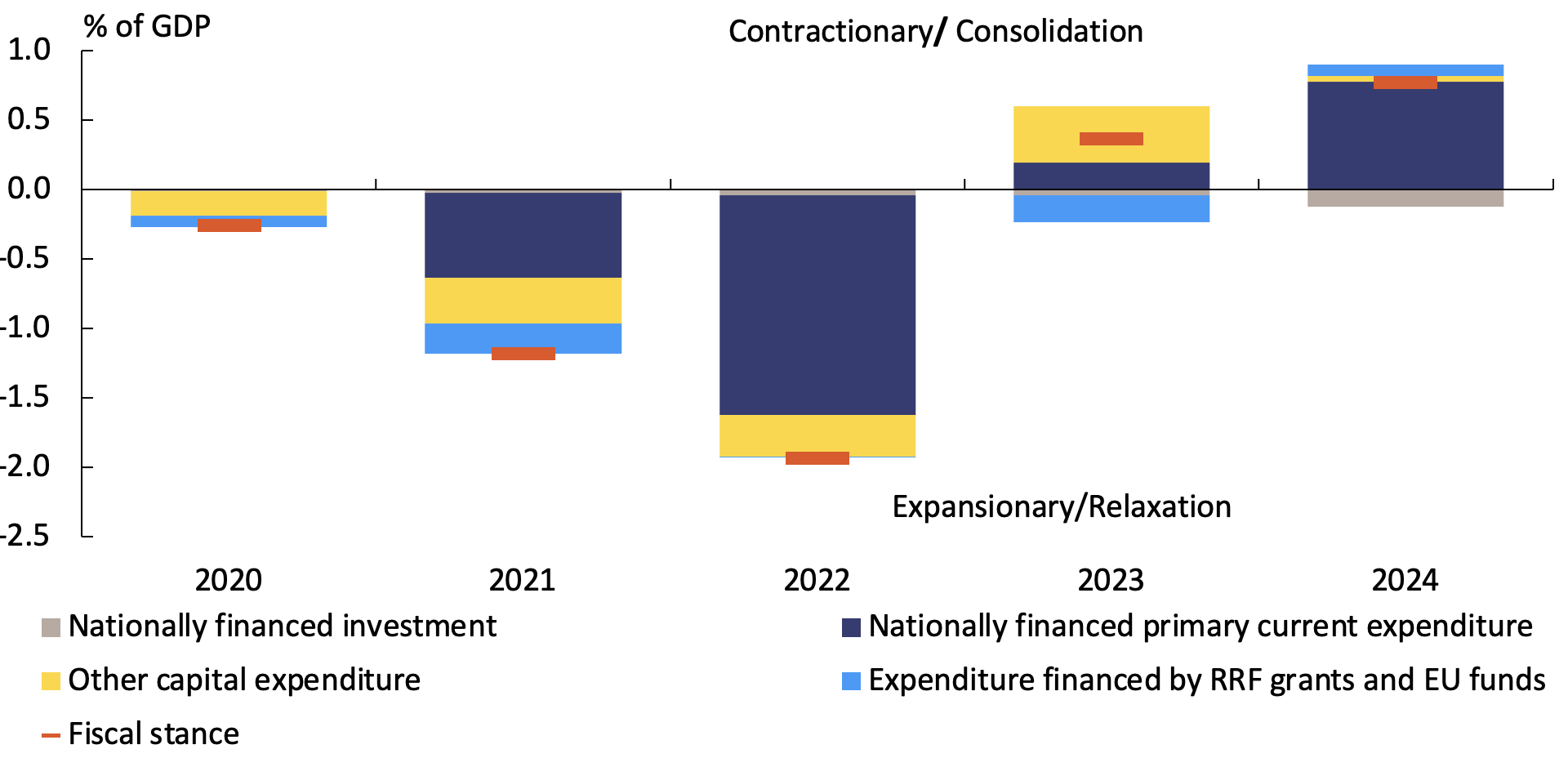

As set out in the Commission Communication on fiscal guidance for 2024, with energy prices having receded, the focus should shift to the phasing out of support measures introduced to protect households and firms from the energy price shock (European Commission 2023b). Such broad-based fiscal stimulus to aggregate demand is unwarranted at the current juncture. The priority must now be to strengthen fiscal sustainability through gradual fiscal consolidation. The contractionary EU and euro area fiscal stances in 2023 and 2024, as projected by the Commission 2023 Spring Forecast, are thus to be welcomed (Figure 4).

Figure 4 EU fiscal stance (% of GDP)

Source: Spring 2023 Commission Forecast

… and support monetary authorities’ efforts to achieve their price stability mandates.

At the current juncture, fiscal policies in the euro area must be consistent with the ongoing normalisation of monetary policy aimed at achieving a timely return to the ECB’s 2% inflation target (Bianchi and Melosi 2019). This provides an additional argument on the need to phase out energy support measures, starting with the least-targeted ones. The focus of policymakers must be on rebuilding fiscal buffers and rechannelling public expenditure to the investments and reforms that are key to supporting the green and digital transitions, including by reducing dependence on imported fossil fuels. If an extension of support measures were to become necessary because of renewed energy pressures, they should be much better targeted than in the past.

Expansionary fiscal policies in the coming years would add to inflationary pressures and further complicate the task of the ECB. This could lead to additional monetary policy tightening down the road, with potentially negative consequences for the financial sector as it seeks to adjust to a higher interest rate environment after a long period of low interest rates (BIS 2023). It could also lead to increased dispersion in sovereign borrowing costs in the euro area, thus putting further pressure on high-debt member states and creating risks for debt sustainability.

Overall, credible commitments to preserve fiscal sustainability and to help anchor medium-term inflation expectations are needed. The legislative proposals for a reformed economic governance framework presented by the Commission on 26 April 2023 should help member states strengthen public debt sustainability and promote sustainable, inclusive, and resilient growth through reforms and investment.

References

Bianchi, F and L Melosi (2019), “The dire effects of the lack of monetary and fiscal coordination”, Journal of Monetary Economics 104: 1-22.

BIS – Bank for International Settlements (2023), speech by Agustín Carstens on “Monetary and fiscal policies as anchors of trust and stability”, April.

Dieppe, A and D Brignone (2022), “Synchronised interest rate hikes, spillovers and risks to global growth”, VoxEU.org, 14 November.

ECB (2021), “Monetary-fiscal policy interactions in the euro area”, ECB Occasional Paper Series No 273.

ECB (2022), “Finding the right mix: monetary-fiscal interaction at times of high inflation”, Keynote speech by Isabel Schnabel, November.

ECB (2023), “Fiscal Policy and high inflation”, Economic Bulletin 2/2023, March.

European Commission (2022), European Economic Autumn 2022 Forecast, European Economy Institutional Paper 187, DG ECFIN, November.

European Commission (2023a), European Economic Spring 2023 Forecast, European Economy Institutional Paper 200, DG ECFIN, May.

European Commission (2023b), “Fiscal policy guidance for 2024”, Communication from the Commission to the Council, March.

Hoffmann, S, M Verwey and G Bethuyne (2022), “The EU economy is at a turning point: The Commission’s Autumn Forecast”, VoxEU.org, 18 November.

IMF (2023), “On the Path to Policy Normalization”, Fiscal Monitor, April.

Motyovszki, G. (2023), “The fiscal effects of terms-of-trade driven inflation”, DG ECFIN Discussion Paper (forthcoming).