First posted on:

mainly macro, 19 April 2018

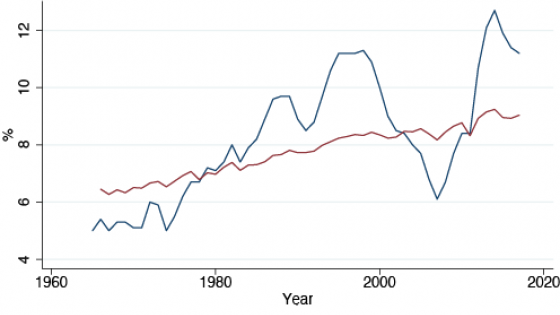

The ongoing debate about whether a Phillips curve still exists partly reflects the situation in various countries where unemployment has fallen to levels that had previously led to rising inflation, but this time, wage inflation seems pretty static. In all probability this reflects two things: the existence of hidden unemployment, and that the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) has fallen. See Bell and Blanchflower on both for the UK.

The idea that the NAIRU can move gradually over time leads many to argue that the Phillips curve itself becomes suspect. In this post, I tried to argue that this is a mistake. It is also a mistake to think that estimating the position of the NAIRU is a mug’s game. It is what central banks have to do if they take a structural approach to modelling inflation (and what other reasonable approaches are there?). Which raises the question as to why analysis of how the NAIRU moves is not a more prominent part of macroeconomics.

The following account may be way off, but I want to set it down because I am not aware of seeing it outlined elsewhere. I want to start with my account of why modern macroeconomics left the financial sector out of their models before the crisis. To cut a long story short, a focus on business cycle dynamics meant that medium-term shifts in the relationship between consumption and income were largely ignored. Those who did study these shifts convincingly related them to changes in financial sector behaviour. Had more attention been paid to this, we might have seen much more analysis and more understanding of finance to real linkages.

Could the same story be told about the NAIRU? As with medium-term trends in consumption, there is a literature on medium-term movements in the NAIRU (or structural unemployment), but it does not tend to get into the top journals. One of the reasons, as with consumption, is that such analysis tends to be what modern macroeconomists would call ad hoc: it uses lots of theoretical ideas, none of which are carefully micro-founded within the same paper. For those who do this kind of empirical work, this is not a choice, but a necessity.

Much the same could apply to other key macroeconomic aggregates like investment. When economists ask whether investment is currently unusually high or low, they typically draw graphs and calculate trends and averages. We should be able to do much better than that. We should instead be looking at the equation that best captures the past 30 odd years of investment data, and asking whether it currently over- or under-predicts. The same is true for equilibrium exchange rates.

It was not just the New Classical Counter Revolution in macroeconomics that led to this downgrading of what we might call structural time series analysis of key macroeconomic relationships. Equally responsible was Sims’s famous 1980 paper, ‘Macroeconomics and Reality’, that attacked the type of identification restrictions used in time series analysis and which proposed instead vector autoregression methods. This perfect storm relegated the time series analysis that had been the bread and butter of macroeconomics to the minor journals.

I do not think it is too grandiose to claim that, as a consequence, macroeconomics gave up on trying to explain recent macroeconomic history, or what could be called the medium-term behaviour of macroeconomic aggregates, or why the economy did what it did over the last 30 or 40 years. Macroeconomics focused on the details of how business cycles worked, instead of how business cycles linked together.

Leading macroeconomists involved in policy see the same gaps, but express this dissatisfaction in a different way (with the important exception of Olivier Blanchard). For example, John Williams, who has just been appointed to run the New York Fed, calls here for the next generationof dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models to focus on three areas. First they need to have a greater focus on modelling the labour market and the degree of slack, which I think amounts to the same thing as how the NAIRU changes over time. Second, he talks about a greater focus on medium- or long-run developments to both the ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ sides of the economy. The third of course involves incorporating the financial sector.

Perhaps one day DSGE models will do all this, although I suspect the macroeconomy is so complex that there will always be important gaps in what can be micro-founded. But if it does happen, it will not come anytime soon. It is time that macroeconomics revisited the decisions it made around 1980, and realise that the deficiencies with traditional time series analysis that it highlighted were not as great as future generations have subsequently imagined. Macroeconomics needs to start trying to explain recent macroeconomic history once again.