A union of states is there for various reasons, but a fundamental one is to provide public goods that cannot be provided optimally by actions at the level of individual states. For example, in the case of union-level public goods, actions by individual states cannot adequately capture the available economies of scale in production, control negative externalities or capture positive externalities, and optimise the tax and transfer systems. Such union-level public goods would be, for example, defence of the union against aggression by other states from outside the union, protection against infectious diseases spreading in the union, regulation of massive population flows into the union, and safeguarding of financial and macroeconomic stability of the union. These kinds of goods are characterised by two important qualities so that they can be classified as public goods at the level of a union of states: ‘nonrivalness’ and ‘nonexcludability’. These concepts are elementary concepts of economics since the work of the renowned economist Paul Samuelson in the 1950s.

Public goods for a union of states are characterised by ‘nonrivalness’ because consumption of these goods by one state does not mean that another state cannot also benefit from them. So, when a state consumes the good of defence against an infectious disease, the same defence is also benefiting the other states in the union. For example, the defence in Italy against COVID-19 is benefiting Italians as well as Germans, French and Swedes. These goods are also characterised by ‘nonexcludability’ because when such goods are produced in one state, it is difficult to exclude other states from benefiting from them. For example, when an EU frontline state such as Greece regulates migration flows from outside the EU at its borders, which are also EU borders, it cannot exclude other, ‘hinterland’ EU states such as the Netherlands, Germany or Belgium from benefiting from this regulation of mass population movements from outside the EU.

One of the most basic raisons d’ être of a union of states is to provide effectively such union-level public goods. If it fails to provide such goods, then the reason and the argument for the existence of such a union is significantly weakened. It actually fails an important long-run viability test. Is the European Union adequately providing these union-level public goods – for example, of defence of the union and its borders against aggression by states from outside the union, protection against infectious diseases spreading within the union, regulating massive population flows from outside the union, and safeguarding of financial and macroeconomic stability of the entire union? Or is it failing to provide these EU-level public goods?

It is arguable that the European Union is showing signs that it is failing this fundamental test of its identity as a union. It is currently facing various such occasions of the test.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the attendant economic shock were unleashed on the EU, the Union was being tested on whether it could provide EU-level public goods. The EU has left Greece and a few other member states to bear the brunt of the attempts of huge numbers of people to enter the Union with final destinations not in Greece but other countries, mostly in the northwestern EU. The Union has also left Greece and other frontline states effectively alone to shelter the many tens of thousands of migrants that manage to get inside EU borders without properly allocating that burden and responsibility throughout the member states. While there have been instances of the EU providing some assistance, say, to Greece, these contributions do not adequately address either the magnitude or the core of the problem. EU actions in this area do not represent an effective EU-level response of appropriate scale based on a far-reaching and bold strategy that is implemented without fail and is adhered to by all EU member states. The EU has also been failing to provide an adequate protection of EU borders and EU sovereignty in general in the context of perpetual and increasingly brazen violations on the part of Turkey. These violations have included those of Greek (and thus EU) airspace and territorial waters; the threatened violation of the continental shelf of Greece and Cyprus; and the asymmetrical warfare organised by Turkey against Greece, using masses of migrants storming the Greek (EU) land border with the logistical and active tactical support of Turkish state security forces. One could also point to the challenges of foreign policy and defence policy, for example vis-a-vis the Middle East (see Syria), North Africa (see Libya), but also elsewhere, as cases of inadequate production of a Union level public good.

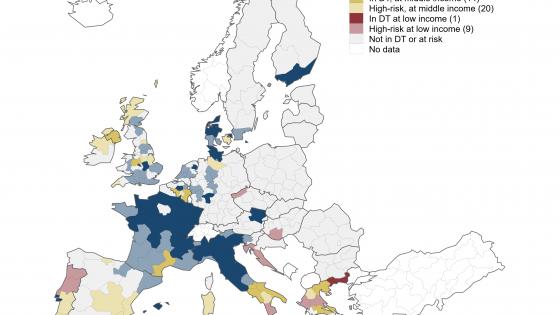

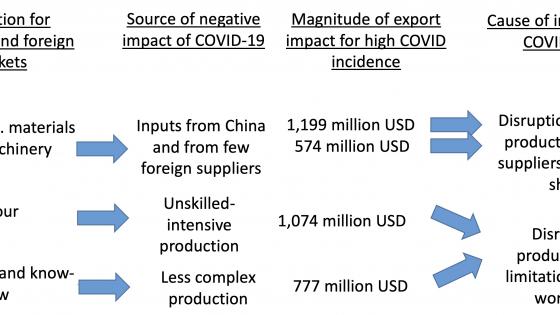

In the last couple of months, the EU has also been failing (so far) to come up with an adequate economic policy response to COVID-19 in the form of an EU-wide fiscal spending package that addresses in a coordinated, consistent and massive enough manner what needs to be addressed wherever there is a need in the Union. Such as to stave off the destruction of significant parts of the supply side of the EU economy; support the EU’s labour force through the stoppage; and ensure care for the needy – all necessary for the EU’s own stability and cohesion. And the troubles of issuing an EU bond to finance member states’ individually inspired spending packages is an example of the power of the contradictions that hamper such well-intended efforts, given that they fall short of a full blown fiscal policy response on the part of the EU as a whole with Union control and responsibility for both spending/revenue generation and financing. Moreover, and very importantly, the EU is failing (so far) to produce a robust EU public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic for the Union as a whole, with meagre resources backing any Union-level actions. Instead, individual member states are left to improvise and struggle to contain the pandemic more or less on their own devices, potentially even undercutting each other’s efforts and undermining basic elements of the union.

And these are only some of the possible examples of the testing of the European Union that is under way.

Certainly, there are some counterarguments that can and will be made with regard to the above bleak picture. Some would point to individual events or acts that may qualify as coordination and collective action, such as the actions announced by the ECB with applicability to those EU member states that have adopted the euro. But most actions taken in the EU are simply not of the type, comprehensiveness and scale that befit the term ‘Union action’ for the critical issues noted above; they are not meeting the criterion of the production of EU-level public goods that provide an important raison d’ être for the European Union. Instead, with its lack of true ‘EU national’ bond, central organisation, and robust and disciplined collective action, the EU is like a ‘sack of potatoes’, to borrow a phrase from Marx’s 1851 Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

The 2020 constellation of challenges for the EU and its member states is a critical one and the dislocations that are already taking place, and will probably be intensified in the period ahead, are going to make more onerous the ongoing test for the European Union. The test has the potential to provide ‘20/20 clarity’ on whether the European Union is a union, functions as a union, and should be called a union. In the end, unless there is a fundamental change of tack and the European Union starts behaving as a union, living up to its responsibilities and offering benefits to its entire population as a union should, the EU may not survive. And that would be a great pity.