First posted on:

PIIE Trade & Investment Watch, 30 July 2018

The Trump administration’s trade wars, which President Donald Trump has said are “easy to win,” encountered a setback in July in what might be called the Battle of the Soybeans. Suddenly the administration was scrambling to find new markets for soybeans in Europe, a dubious proposition, and to spend federal funds to protect American farmers from the retaliation provoked by the administration’s reckless tariffs. The soybean skirmish illustrates the utter wrongheadedness of the president’s approach to trade.

Two policy wrongs illustrate the point. First, on 24 July, the administration announced plans to subsidise American farmers for up to $12 billion for their suffering of lost export sales resulting from the president’s own escalating tariff actions. Trump’s 2018 tariffs-to-date on steel, aluminium, and China have caused the EU and five other major trading partners to implement retaliatory actions affecting $27 billion of US agricultural sales to the world. Trump’s tariffs suddenly put 20% of total American agricultural exports at risk.

Second, on 25 July, Trump made an unexpected insert at a press conference with European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker, proclaiming a truce in the European trade confrontation and announcing renewed trade negotiations. There, Trump took great pains to highlight American soybeans now largely shut out of the Chinese market. Without any mention of how, he stated “soybeans is [sic] a big deal and the European Union is going to start almost immediately to buy a lot of soybeans…from our farmers in the Midwest primarily.”

There was more than grammar that was wrong with Trump’s statements. The potential “truce” involved no pullback on trade by either side. More specifically, it did not lead to the lifting of Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminium imports from Europe. Neither did the EU lift its newly imposed tariffs on $968 million of American agricultural exports. And how Trump expects the EU to suddenly sop up all of those American soybean exports shut out of the Chinese market is unclear. European countries are market economies. That means that purchasing decisions are mostly made by businesses and consumers and are not directed by heavy-handed, central-planning governments.

Soybeans are indeed a “big deal.” They are widely consumed around the world by humans and livestock. Lost soybean sales to China may be the biggest blow to American farmers, but they are far from the only agricultural product caught up in Trump’s trade war. His policy has led to retaliatory tariffs against $13 billion of other agricultural exports covering dozens of other farm and fishery products. Besides China and Europe, four other partners are also retaliating against his steel and aluminium tariffs. And tens of billions of dollars of additional retaliation loom if the administration follows through with threats to slap additional trade restrictions on automobiles, whose “national security threat” investigation continues.

American agricultural exports subject to foreign retaliation thus far

To date, six different trading partners are retaliating against US agricultural exports in response to Trump’s 2018 binge of tariffs imposed on steel, aluminium, and China. A total of $27 billion of American agriculture exports are being affected. While farm exports to China account for nearly 75% of the total, Canada, the EU, Mexico, India, and Turkey have also whacked a combined $7 billion of American agricultural exports in response to Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminium.

Figure 1 begins by tallying up the status of the major animal-based export products. Newly imposed foreign trade restrictions are now hitting a significant share of total American exports of dairy ($812 million), fish and shellfish ($1.3 billion), as well as pork ($2.4 billion). Importantly, not all meats have been targeted yet – few of the retaliatory tariffs have hit poultry or beef, for example. There is therefore ample scope for other agricultural products to get caught up in the fray of Trump’s trade war.

Figure 1 US exports of major animal-based products, 2017

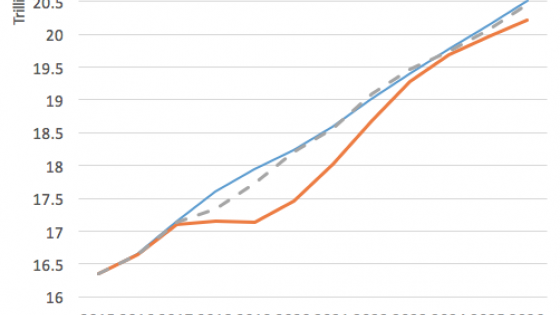

Figure 2 indicates a similar story for major crop exports. American exports of soybeans were $21.7 billion in 2017, and 64% ($13.9 billion) have been targeted with retaliation thus far.

Figure 2 US exports of major crops, 2017

But nearly $1 billion each of annual exports of nuts, sorghum, and fruits have also been impacted by the tariffs arising in response to Trump’s policies. This is particularly problematic for a product like sorghum, where 89% of foreign sales have been hit with tariffs. It has developed few other foreign markets to send its lost exports.

And there is still scope for more pain. Other major export crops such as corn, wheat, and rice have been less directly caught up in the tariff war – they also could be hit if Trump continues on his trade offensive.

The table here provides a longer list of major American agricultural exports, many of which are also caught up in the retaliation. Take apples, orange juice, coffee, ketchup, and mineral water. More than a third of each products’ exports to the world are now caught up in foreign tariff actions.

Particularly illustrative is the challenge facing a product like whiskey, frequently tagged with Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader from Kentucky. Four different partners have targeted whiskies with their tariffs, thereby hitting more than half of American exports of the product. Whiskey being shut out of multiple foreign markets all at once makes it even more difficult for it to find viable alternative destinations for its sales.

US law Trump is using to grant the subsidies

Trump’s $12 billion subsidy to help soybean farmers at home invoked a 1933 law devised to assist farmers hit by the Great Depression. While potentially troubling, the move was not unexpected. The president had instructed Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue to come up with such a plan on 5April, shortly after China announced it would retaliate against US agricultural exports in response to Trump’s 3 April statement that he would impose tariffs on $50 billion of US imports from China.

On 25 July, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) released a statement indicating its plans for a three-pronged programme intended to provide support for American farmers under the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) Charter Act, the 1933 policy created by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

At this stage, details remain thin on how the Trump administration plans to implement the subsidy scheme. But the most economically significant part of the plan is likely to involve direct payments to producers – the announcement indicates only to soybean, sorghum, corn, wheat, cotton, dairy, and hog farmers – under the CCC’s Market Facilitation Program. The timeframe and mechanism are still unknown, as is whether direct payments would flow to other farmers cut up in the tariff retaliation.

The announcement describes two other actions that are likely more minor. One is a potential food purchase programme to buy up unexpected surplus of affected commodities – e.g. fruits, nuts, rice, legumes, beef, pork, and milk – for distribution to food banks. Another is additional spending on foreign sales offices and fairs. This last step is probably the most misguided of all – a feckless attempt to open foreign markets that have been willfully and deliberately shut off as a policy choice because of Trump’s actions. Paying bureaucrats to promote sales of farm products would be an incredibly inefficient means of immediately compensating the American farmers whose incomes are suffering because of lost export sales.

Are these subsidies illegal under international trade rules? They could be. Under the WTO, the US has agreed to limit trade-distorting farm-sector support – as measured by the aggregate measurement of support (AMS) – to $19.1 billion per year. While it may be possible for the USDA to carefully construct a subsidy scheme that is decoupled from market signals – and so is not trade-distorting – Trump’s subsidies will generate scepticism by trading partners and could be challenged under WTO dispute settlement. At the least, Trump’s short-sighted actions will make it more difficult for future American negotiators to convince trading partners – like India or China – to reign in their own agricultural subsidies.

There is the potential for further escalation. Countries could respond with more tariffs – or even subsidies of their own – if they perceive that the new subsidy policies of Trump’s widening trade war pose an additional threat to their farm sectors.

Trump’s bad policy choices are piling up

There is no end in sight for Trump’s trade war.

President Trump’s reckless tariff actions of 2018 have been the direct cause of considerable economic hardship now looming for American farmers. The political problem that this creates has caused his efforts to buy them off by providing payments funded by the American taxpayer.

Two wrong policies don’t make a right. The farmers are being hurt, and they surely prefer to get their old markets back. But the only way for that to happen will be for President Trump to ultimately remove his 2018 tariffs.