Official statistics on national product and income per person are not enough to describe the economic life of a nation in full. Such figures need to be assessed in a broader context. No sane investor would consider valuing a security solely in terms of its expected yield. Securities need to be evaluated in two dimensions: in terms of risk as well as return. The same logic needs to be applied to the national product. It is not enough to know the volume of national output, we also need to know how it is distributed across the population.

Consider two countries with the same output per person but a grossly dissimilar distribution of income and wealth. Suppose that in one country a small group of people gathers almost all the income and owns almost all the assets, while in the other one income and assets are much more evenly distributed. Which of the two countries would you rather live in? In which one do you think most voters would rather live? The second question answers itself.

The distribution of income and wealth was off the beaten path of most economists until recently, when inequality finally made its way into the mainstream of economics, where it belongs. Official statistics on the distribution of income, and especially wealth, are still incomplete, in part because a lot of money remains hidden away in tax havens. Assets equivalent to perhaps 10% of annual world output are unaccounted for (Zucman 2015).

Many rooms, many dimensions

Two dimensions are not enough. We need to know the national product and how it is divided among the population, true, and we also need to know and understand whether the economic and social foundation on which the production rests is gaining or losing ground.

Consider two countries with the same national product per person and the same distribution of income and wealth, but grossly dissimilar treatment of the environment. Suppose that in one country the forests, fishing grounds, and other resources are being depleted, education is in decline, and pollution is spoiling the natural environment, while the other country’s resources are managed sustainably, education is in good shape and environmental protection as well. Which country would be a better place to live in? This question also answers itself.

We can ask similar questions about transparency, trust, health, democracy, and so on. In the house of economics, there are many rooms, many dimensions, just as in physics where string theorists need no fewer than 26 dimensions to tell some of their stories, but I digress.

Democracy

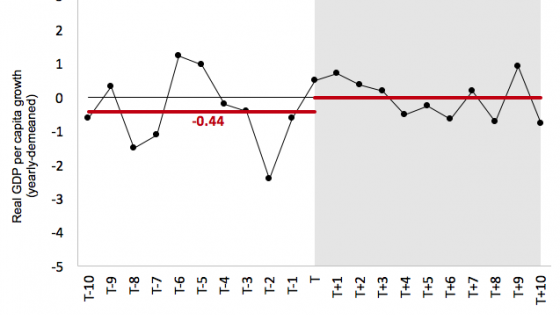

Let us consider one of these quasi-economic dimensions – democracy. It wasn’t until recently that economists began to pay due attention to democracy as an economic variable of sorts. It happened when economists finally realised that long-run economic growth is governed by economic laws and not just technological progress. We now think we know that high inflation and bad economic management generally undermine economic growth regardless of technology, as elementary logic suggests, and experience has demonstrated. The same applies to several other factors, not just economic variables in the traditional sense, but also political variables (e.g. democracy) and social indicators (e.g. longevity) (Gylfason 2019).

The value of longevity is self-explanatory. Long lives and good health are desirable in themselves, and as promoters of productivity and growth. The revolution in living standards across the globe since 1960 is sometimes even better described by improved public health and longer lives than by rising incomes. Since 1960, China and India have each year added nine and five months, respectively, to the average life expectancy of their citizens.

Democracy is a bit more complicated. For a long time, social scientists had difficulty coming to grips with the linkages between democracy and economics because, until the 1990s, most economists thought they knew that long-run economic growth was immune to all but technological progress, as improbable as that must sound to modern ears. Therefore, many did not take full account of the empirical finding of political scientists that per capita national product and democracy tended to go hand in hand from one country to another. Then, like thunder, came the discovery that economic growth does – but of course! – depend on many other things: investment, education, trade, and infrastructure (good governance, independent judiciaries, free press), and more.

And then, at last, we were bound to ask: What can we say about the relationship between production and democracy?

Even before the data processing got into full swing, two points of view were raised. Some said: Democracy plays into the hands of insistent, greedy interest groups, thus reducing efficiency and undermining economic growth. Others said: Democracy allows all voices to be heard and, to cite Mao, a thousand flowers to bloom, facilitates peaceful changes of government, and thus promotes efficiency and growth.

Statistical studies of the relationship between democracy and growth have not yet removed all doubts about which of these two opposing viewpoints appears to have stronger merits. One source of the uncertainty is that dictators tend to falsify national accounts to make their economic performance appear more impressive than it is. In some autocracies, including China, the national product may, in truth, be only half the size reported in national accounts if satellite images of night lights on earth are anything to go by (Martínez 2022). Therefore, official statistics showing high incomes and rapid growth under authoritarianism need to be taken with a grain of salt.

A key metric of democracy, the Freedom House Democracy Index, divides countries into three categories: free, partly free, and unfree based on the scores awarded to them for political and civil rights. Martínez shows that in free countries, official figures on the national product go hand in hand with the night lights on earth shown in satellite images, without significant deviations. In unfree countries, on the other hand, the night lights are much dimmer than the official output figures would suggest. Autocracies typically exaggerate their national product by a factor of two or more. We knew this about China, from studies that report that the annual growth of the national product has been 2% less than the official figures indicate. Now we need to take a fresh look at the national accounts of Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and more.

The anocracies, midway between democracies and autocracies and described by Freedom House as partly free, also tend to exaggerate their national output, typically adding 28% to their national output figures to make them look better, not 104% like in autocracies, not to mention 2% like in democracies.

Recent research seems to support the hypothesis that democracy encourages economic growth and vice versa (Acemoglu et al. 2019). Like other human rights, democracy is like public health in that they are all desirable in themselves, so much so that human rights are universal in the sense of the law, and therefore trump other legal provisions according to international human rights treaties. Thus, the United Nations Human Rights Convention stipulates that individuals can be held legally responsible for violating human rights, albeit not for keeping people in poverty if this is done without human rights violations.

Be that as it may, economists have awakened to the crucial question about the relationship between production and democracy around the world. Thanks to long experience with such measurements, production is easy to gauge, however imperfectly as stated before and subject to appropriate corrections due to falsification of data. Democracy, multifaceted as it is, is more difficult to deal with. Social scientists rely on three main sources of data on democracy around the world.

Maryland

One of the main democracy metrics in use was initially compiled by political scientists at the University of Maryland (Polity5 Project, Center for Systemic Peace). It covers the period from 1800, when democracy saw the light of day again, until 2018 when the data collection was paused. The index is woven together from many threads of democracy, which revolves round more than free elections at regular intervals. The democracy index ranges from -10 in hardcore dictatorships (e.g. Saudi Arabia) to +10 in unfettered democracies (e.g. Sweden). The number of democracies has increased from zero in 1800 to 100 in 2018, while the number of autocracies rose from 10 in 1900 to 90 in 1990, before falling back to 20 in 2018.

Thus, the situation in 2018 was this: 100 democracies, 50 anocracies, and 20 autocracies. There were more democracies in 2018 than ever before, but democracy has been in retreat for most of the years since 2006 (Diamond 2020). Even the US no longer qualifies for the top rating of +10 for democracy; its rating was lowered to +8 in 2016 and remained there in 2017 and 2018. Figures for the years 2019-2023 will be published in 2024. It has been reported that the US dropped out of the democracy category with a score of +6 in 2020 and was classified as anarchist (+5) towards the end of 2020, but its score was raised again to the democratic category in 2021 (+8).

Washington, DC

Freedom House has also compiled democracy indices for most of the world’s countries for the past half century, dividing them into three categories: free, partly free, and unfree based, as said before, on the scores given to the countries for political and civil rights. Freedom House gradually lowered the US democracy score from 93 for 2013 to 83 for 2022.

Gothenburg

In recent years, the University of Gothenburg’s Institute for Democracy (V-Dem Institute) has developed a new composite democracy index for most of the world’s countries along the same lines as the other two data banks. On the Gothenburg list, the US ranks 29th out of 179 countries. Sweden and Denmark occupy the top two places. Russia is in 151st place and China in 172nd place.

The political scientists in Gothenburg divide democracy into four categories: liberal democracies, electoral democracies, electoral autocracies, and closed autocracies. The figures confirm the decrease in the number of open democracies since 2006. The decline of democracy can thus be seen in two ways: via lower scores for countries that are still classified as democracies, such as those in Maryland, as well as via the drop in the number of democracies, as in Gothenburg. There is no inconsistency here, only different emphases and definitions.

In conclusion

Democracy is one of the greatest inventions of humankind, next to fire, the wheel, and marriage as I see it, and has produced great results across the board.

The main benefit of democracy is not that it always delivers the best possible result and best possible governance. No, the main benefit of democracy is that it entails that we, the people, must accept the rules of the game of democracy, including election results, whether we like them or not.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Naidu, P Restrepo, and J A Robinson (2019), “Democracy Does Cause Growth,” Journal of Political Economy 127(1): 47-101.

Diamond, L (2020). “Breaking Out of the Democratic Slump,” Journal of Democracy 31(1): 36-50.

Gylfason, T (2016). “Economic Performance in Two Dimensions: How Europe Beats the US”, VoxEU.org, 22 August.

Gylfason, T (2019) “From Equality, Democracy, and Public Health to Economic Prosperity”, ifo.

Institute for Democracy, Gothenburg University (2022). V-Dem Institute.

Martínez, L R (2022), “How Much Should We Trust the Dictator’s GDP Growth Estimates?”, Journal of Political Economy 130(10): 2731-2769.

Zucman, G (2015), The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens, University of Chicago Press.