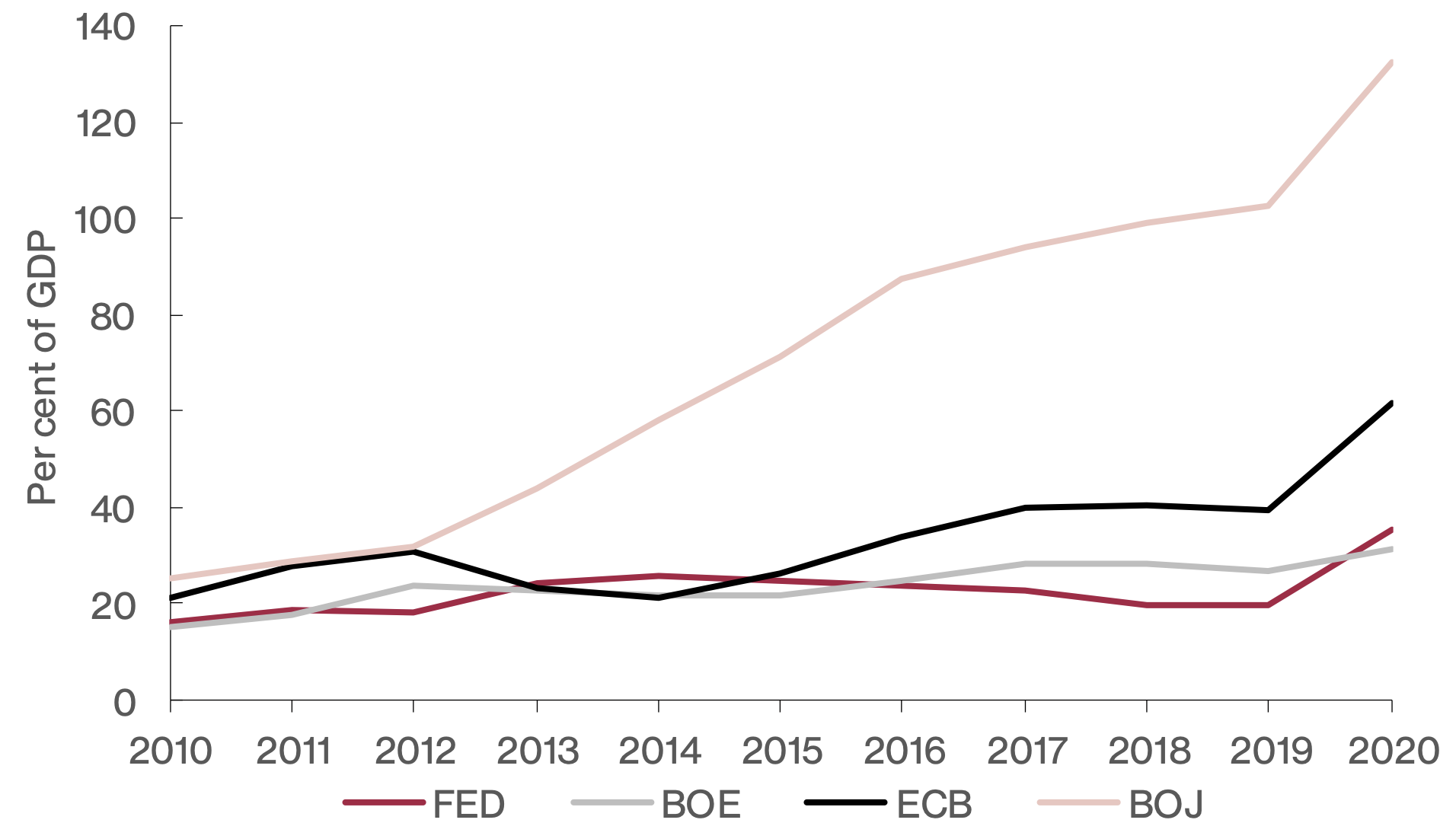

Since the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, monetary, regulatory and fiscal policies have deepened the interconnections between the balance sheets of the central bank, the commercial banks and the government. Quantitative easing (QE), in which central banks buy long-term government bonds (to lower long-term interest rates), has created a rapid escalation in commercial bank reserve balances with the central bank. In addition, liquidity rules introduced after the global financial crisis have required commercial banks to increase their liquid asset holdings, including both reserve balances with the central bank and government securities (see Chadha et al. 2021a).

Figure 1 Major central bank balance sheets, 2010-20

A threat to central bank independence

These developments threaten central bank independence and budgetary sustainability. Monetary policy now has large fiscal implications. When, for example, central banks begin to tighten monetary policy and raise rates (or when international long-term interest rates increase), there will be substantive implications for fiscal sustainability (Allen 2021 and Landau 2020). In the UK, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR 2021a) has underlined that even a modest rise in Bank rate with parallel moves along the yield curve might make it harder to stabilise the government debt-to-GDP ratio. In the United Kingdom, the independent Office for Budget Responsibility has carried out such an examination (2021b), and has identified plausible scenarios in which the public finances become unsustainable.

In this environment, there is a risk of central banks being put under pressure to keep interest rates low to manage government debt service costs. In other words, there is an unusually serious threat to central bank independence. Even the appearance that independence has been compromised would be dangerous. And because of the inter-connections among policy instruments, the transition to higher interest rates may be especially difficult. Achieving the transition while maintaining the independence of the central bank is crucial.

Reducing the interdependence between central banks and Treasuries

The central bank and the Treasury should consider how adjustments in their respective balance sheets could reduce the risk that fiscal considerations might inhibit a future tightening of monetary policy. Central banks may not be able to sell their large holdings of government bonds as quickly as they bought them, or as quickly as they might want to, for fear of damaging the structure of bond markets. The risk of disruption is more serious for long-dated than short-dated bonds, because long-dated markets are typically less liquid.

We argue that, once we enter the exit phase, these sales would be better managed by the Ministries of Finance, in the UK this means H M Treasury. It is the Treasury, not the central bank, that is responsible for the domestic policies which affect bond markets – that is, the medium-term fiscal framework and the sequence of current and expected government budget decisions. Moreover, it is responsible for the programme of bond sales that finance budget deficits and the redemption of maturing debt.

We propose limiting even the appearance of conflicts between the Treasury and the central bank when macroeconomic policies have to tighten. We do not discuss changing the monetary-fiscal policy mix. But our proposals would clear the decks for a future policy tightening by providing the central bank with securities that would be easier to sell. That would make it easier to conduct monetary policy, and it would mean that monetary policy actions were less consequential for fiscal policy. The roles of monetary and fiscal policy would be disentangled, so that each could be managed separately in pursuit of its own objective (analogous to the analysis of Mundell 1962).

The central bank balance sheet

Central bank assets

We propose that the central bank and the Treasury make the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet more liquid by conducting a swap of securities with the Treasury. The central bank would exchange with the Treasury all or part of its portfolio of long-term government bonds acquired under QE for a newly created portfolio of shorter maturity bonds (short-term bills or short-medium term bonds). This would reduce present huge maturity mismatch (long-term assets with very short-term liabilities) on the central bank’s balance sheet.

The transaction would be wholly within the public sector, so that the consolidated balance sheet position of the public sector vis-à-vis the outside world would not change. The central bank would continue to roll over its holdings of government debt and banks’ reserve balances would remain unaltered. Hence the QE monetary stimulus would remain in effect until macroeconomic conditions dictated otherwise.

Our proposal involves the transfer of interest rate risk from the central bank to the Treasury. That would make no real difference in the U.K. case because the Treasury has indemnified the Bank of England against losses on bond purchases under its QE measures, and has already received the benefit of profits. Thus far, the programme has been very profitable for the Treasury, but it is very risky. The UK’s Asset Purchase Facility, the account in which the bonds are held, has so far yielded £112 billion to the Treasury. Paying the banks for the reserves created by QE has so far proved to be much cheaper than paying bond holders. The reverse would however apply if and when interest rates rose above the levels implied by current bond yields.

If the proposed transaction were not done, and bond yields rose more sharply than current bond market prices suggest, how might politicians and the public react to the losses that would be recorded by central banks such as the Bank of England? One can imagine accusations about the central bank being bailed out by the government and accompanying damage to central bank credibility. Moreover, the terms of the indemnity have not been published, for reasons that are not clear (House of Lords 2021).

The macroeconomic logic should be that sales will be larger when monetary restraint is required and slower when the economy weakens. If used in this manner, quantitative tightening – the opposite of quantitative easing - could become a useful monetary policy tool.

This proposal would in no way impair the independence of the central bank. It would not limit its ability to decide on operations in government bond markets if needed for monetary policy purposes. Such operations used in an expansionary direction were effective in 2009-2012. Long-term interest rates were reduced by QE, with significant macroeconomic and financial stability benefits at a difficult time (Gagnon 2016, Turner 2021). More recently, the prompt and substantial response of monetary policy to the coronavirus pandemic was a vital complement to expansionary fiscal policy in limiting output and employment losses (Chadha et al. 2021a, 2021b). But it would be impossible for central banks to sell government bonds of similarly long average maturity at a similar pace when restrictive monetary policy was required. If the maturity of the central bank’s bond portfolio were to be shortened, as we have suggested, the central bank would have more flexibility in tightening policy. If it wanted to sell bonds to tighten policy, it would transfer bonds from its portfolio to the Treasury in exchange for Treasury bills, and ask the Treasury to sell them in the market over a certain period. The central bank could choose whether to retain the Treasury bills, rolling them over on maturity, or allow them to run off (or sell them) and have the commercial banks’ reserve balances fall back in parallel.

Central bank liabilities

Most central bank liabilities are the assets of private financial institutions. The main central bank liability created by QE has been bank reserves – very short-term deposits of commercial banks which have since 2009 been remunerated at Bank Rate. Currently reserves at the Bank of England are about £800 billion (36% of GDP), and are still rising. The interest-paying liabilities of the Fed are about $4.5 trillion (20% of GDP). As already noted, such large reserves have made central bank payments to banks more sensitive to changes in the policy rate.

Rather than ending or curtailing the payment of interest on reserves, we would prefer to convert some proportion of banks’ reserves into shorter maturity government bonds (Allen 2021). The conversion would have to be compulsory, since an auction of a very large amount of bonds would certainly be undersubscribed. Such a measure could be made more palatable for the banks by exempting short duration government bonds from the leverage ratio. How much to convert would depend on an assessment of the structural demand for reserves, which has greatly increased since the global financial crisis. At current yields, the interest cost to the government would be low. This policy would transfer some interest rate risk to the banks. Regulatory stress tests on banks for a sharp rise in bond yields would be needed.

The conversion would replace a bank asset of zero maturity with assets of, say, 2-year average maturity (McCauley 2021 makes a similar proposal). The banks would therefore have to sell or hedge some bonds if they wanted to keep the duration of their interest rate exposures constant. Yields on government bonds would rise. A modest first step could test the size of such an impact.

After the operation had been conducted, the maturity structure of government debt held in the market, and hence the interest rate risk exposure of the government, might not be what the Treasury wanted. It would be open to the Treasury to adjust the maturity structure over time as it saw fit.

Conclusion

Government debt/GDP ratios have risen sharply. Major central banks maintain substantial purchases of government bonds. Higher interest rates will inevitably have large effects on the balance sheets of the central bank, the government and the commercial banks. There is a strong case for considering balance sheet adjustment now when interest rates are still low. This is why the current debate on this issue is important. In order to protect the independence of the central bank there is a case for alternative arrangements which better clarify the separation between monetary policy and fiscal policy. Cautious but early action is the order of the day.

References

Allen, W A (2021), “Managing the fiscal risk of higher interest rates”, NIESR Policy Paper 25, 26 March.

Blinder, A S (2010), “Quantitative Easing: Entrance and Exit Strategies”, Federal Reserve bank of St Louis, Review, November/December.

Allen, W, J Chadha and P Turner (2021), “Commentary: Quantitative Tightening: protecting monetary policy from fiscal encroachment”, National Institute Economic Review 257: 1-8.

Chadha, J S, L Corrado, J Meaning, and T Schuler, (2021a) “Bank reserves and broad money in the global financial crisis: a quantitative evaluation”, ECB Working paper No. 2463.

Chadha, J S, L Corrado, J Meaning and T Schuler (2021b). “Monetary and fiscal complementarity in the COVID-19 pandemic”, Covid Economics 81, June.

Dale, S (2011), “QE – One Year on”, in J S Chadha and S Holly (eds), Interest Rates, Prices and Liquidity Lessons from the Financial Crisis, pp. 222 - 232

Gagnon, J E (2016), “Quantitative Easing: an under-appreciated success”, Petersen Institute for International Economics Policy Brief PB16-4.

House of Lords (2021), Quantitative easing: a dangerous addiction?, Economic Affairs Committee 1st Report of Session 2021–22.

Landau, J-P (2020), “Money and debt: paying for the crisis”, VoxEU.org, 23 June.

McCauley, R (2021), “Unstuffing banks with Fed deposits: Why and how”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Mundell, R (1962), “The appropriate use of monetary and fiscal policy under fixed exchange rates” International Monetary Fund Staff Papers 10, pp. 70-77

Office for Budget Responsibility (2021a), Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2021.

Office for Budget Responsibility (2021b), Fiscal Risks Report, July.

Turner, P (2021a), “A new monetary policy revolution” NIESR Occasional Paper no 60. February.