First posted on:

modelsandrisk.org, 10 February 2018

As the financial press had it, the financial markets had quite a dramatic week.

Put in context, how dramatic was the week that ended on 9 February?

When I was at university, one of the professors had his students subscribe to the Wall Street Journal and collect explanations for financial news. Roughly half the time, the Journal explained interest rate increases by exchange rates appreciating, while the rest of the time, rate increases were caused by exchange rates falling. It was the same with other events. Fake news, or should I say random news, is not a modern phenomenon.

Stock prices reflect future profits, so when the discount rate increases or we find we have been too optimistic, prices drop. And it doesn’t take all that much in terms of changes in discount rates or expectation to get last week’s outcomes.

So someone tasked with explaining market turbulence just needs to find some indication that discount rates or expectations of the future changed. The easiest is to pick the biggest news of the day and say “that is the reason”. But there is a large number of different news items that can have the same impact on prices.

Therefore, attributing last week turbulence to inflation, or whatever, is a bit disingenuous.

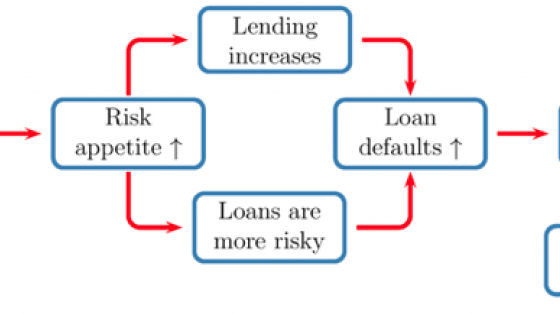

The lesson from our work on perceived risk and actual risk is that there is an almost infinite number of triggers and a very small number of mechanisms. Focus on the mechanisms not the triggers.

The main crash day was Monday, and I discussed that the next day.

Now that the week is over, I can look at volatility, in this case realised volatility. The following figure shows the weekly volatility from 1929, with a red line drawn through the data the level of last week’s volatility.

It was certainly one of the higher data points, but by zooming into this decade, it becomes clearer. It doesn’t look all that extreme.

So how big was last week’s volatility in a historical context? Let’s look at the biggest weekly volatilities in my history, and plot them sorted, identifying the four biggest as well as yesterday’s:

Not surprisingly, the worst is in the 1987 crash, followed by two observations from the Great Depression and October 2008.

By comparison, last week's is relatively minuscule, the 103th highest volatility. The history is 88 years, so last week’s volatility shock was a once-every-10-month shock. Not all that extreme, was it.

So, last week looks not nearly as dramatic as the financial press would have it.

An attack by a toothless dragon...

We generally get volatility wrong. It has been low for some time. However, volatility does not capture risk or uncertainty in the way most people think. Volatility goes up when our opinion of the world changes. If it doesn’t, volatility is low, regardless of whether the news is good or bad.

So, sound and fury signifying little beyond newspaper headlines.