The EU, the UK, and the US have sought in recent months to discourage Russia from sending military forces into Ukraine. Diplomatic missions have been complemented by promises of military support and training for the government in Kyiv. Whether these steps persuade the Russian government to stand down their troops down remains to be seen.

Current developments have unwelcome echoes to the annexation of Crimea undertaken by Russia during the first quarter of 2014, which many have observed was the first of its kind in Western Europe since the conclusion of World War II. After that annexation, steps were taken by Western governments to offer economic support to Ukraine, often in the form of better market access.

Was that trade policy support sustained? Or was policy incoherent – with lofty diplomatic objectives undermined by below-the-radar screen trade policy interventions that impaired Ukrainian access to Western markets? The purpose of this blog is to address these questions. But first it is worth remembering the defence-related consequences of overseas market access.

Without well-equipped and sufficiently trained armed forces, a nation’s foreign adversaries are less likely to be deterred from military action. Having the tax base to afford effective national defence forces is key and export revenues that result in economic growth help in this regard.1 Improved and secure access to the markets of allies is especially important when export sales to other markets and production facilities are lost due to earlier hostile acts by neighbouring nations.

In recent years we’ve been told that economic security is national security, claims that have been rightly derided when they were advanced by Trump administration officials. However, such arguments may be of greater relevance in the Ukrainian context. For sure, Ukrainian prosperity is not the sole responsibility of Western governments, but a prosperous Ukraine that can defend itself is evidently in the Western interest.

Ukraine is no export powerhouse

At this stage it is useful to put some facts on the table. According to the latest WTO Trade Profiles, Ukraine exported just under $50 billion in 2020. Over the decade 2010 to 2020 Ukraine’s exports stagnated and its national imports actually fell on average 1% per annum. Trade as a percentage of Ukraine’s GDP is less than 45%, which is well below neighbours Belarus (65%) and Poland (53%) and slightly ahead of Moldova (42%). The amount of trade per head in Ukraine in 2020 was $1,556, a fraction of these three neighbours. The upshot: over the past decade Ukraine has not been a poster child for export-led growth.2 The implications of this missed opportunity may soon extend beyond the pocketbooks of Ukrainians.

Ukraine’s exports of agricultural goods are unusually high, amounting to 45% of national exports in 2020. Manufactured goods, which often face fewer trade restrictions, accounted for 42.5% of total exports. Over a third of Ukraine’s exports go to the EU (36.5%), followed by China (destination to 14.5%) and Russia (which despite its sustained measures against Ukrainian goods absorbs 5.5% of that nation’s exports). By 2020 the UK and the US were still not among the top five export destinations for Ukrainian goods, even though the distance from Kyiv to Washington DC is just 21% longer than that to Beijing.

EU trade policy stance towards Ukraine: A comparative perspective

The EU views its trade policy as an important lever of influence in its neighbourhood, including the pursuit of peace and regional stability. Following the annexation of Crimea, the EU implemented temporary market access improvements to certain Ukrainian exports in April 2014 as well as a programme of Macro Financial Assistance.3

Subsequently, an Association Agreement including a Comprehensive and Deep Free Trade Area with Ukraine was ratified completely by 1 September 2017. It is important to state that this “deep free trade area” did not lead to the immediate creation of a full-blown regional trade agreement in the traditional sense, although it did include a standstill provision for import tariffs imposed on goods from the other party (see Article 30).

Following ratification of the Association Agreement, on 13 September 2017, the EU unilaterally granted “autonomous trade measures” that afforded better market access to Ukraine’s exports of selected agricultural and industrial products. These measures that lasted three years and lapsed on 30 September 2020. One area of trade tension was an export ban on wood imposed by Ukraine that the EU took to an arbitration proceeding.

But what of other unilateral trade policy measures taken by the EU since the start of 2014? On net, did those trade measures open EU markets for Ukrainian exporters or did they close them? And what is the right way to benchmark the consequences of unilateral EU trade policy choice?

To answer these questions information was extracted on those commercial policy interventions in the Global Trade Alert database that involved changes in EU4 policies affecting imports5 on or after 1 January 2014 of products that Ukraine exported. Only those trade policy changes still in force on 13 February 2022 counted towards the analysis presented here. A total of 51 trade policy changes were identified, 36 of which involved some change in import tariff rates. Twenty-eight of those 51 trade policy changes improved access to EU markets for Ukrainian goods. Very few of these trade policy changes specifically singled out Ukrainian exports.

To benchmark EU trade policy changes towards Ukraine, the same exercise was repeated for Belarus (an ally of Russia) and Georgia (a nation that has witnessed the sharp end of the Russian military). This facilitates comparisons of EU trade policy across these three nations. In addition, information was extracted on the same set of trade policy changes implemented over the same time horizon by the UK, the US, and the rest of the world (ROW), the latter defined to exclude Russia, the EU, the UK, and the US. In turn, this allows readers to contrast the implications of EU unilateral trade policy choice towards Ukraine’s exports to that of other Western nations and to a global average. In what follows the implementing nations refer to the EU, the ROW, the UK, and the US and the exporting nations refer to Belarus, Georgia, and Ukraine.

To gauge the export exposure to foreign trade reforms and restrictions since the start of 2014, the most disaggregated United Nations trade data available6 was used to estimate the exports covered by each implementing nation’s trade policies that were in force on 13 February 2022.7 As each implementing nation imposed both liberalising and restrictive trade policies, the following calculations were made for each exporting nation (a) the percentage of its total exports that face liberalising measures in an implementing nation, (b) the percentage of its total exports that face import restrictions in an implementing nation and (c) the difference between (a) and (b), which we refer to as the net percentage of exports exposed to trade policy changes by an implementing nation. The latter difference provides an overall estimate of the net change in market access resulting from the implementing nation’s unilateral trade policy decisions since the annexation of Crimea.8

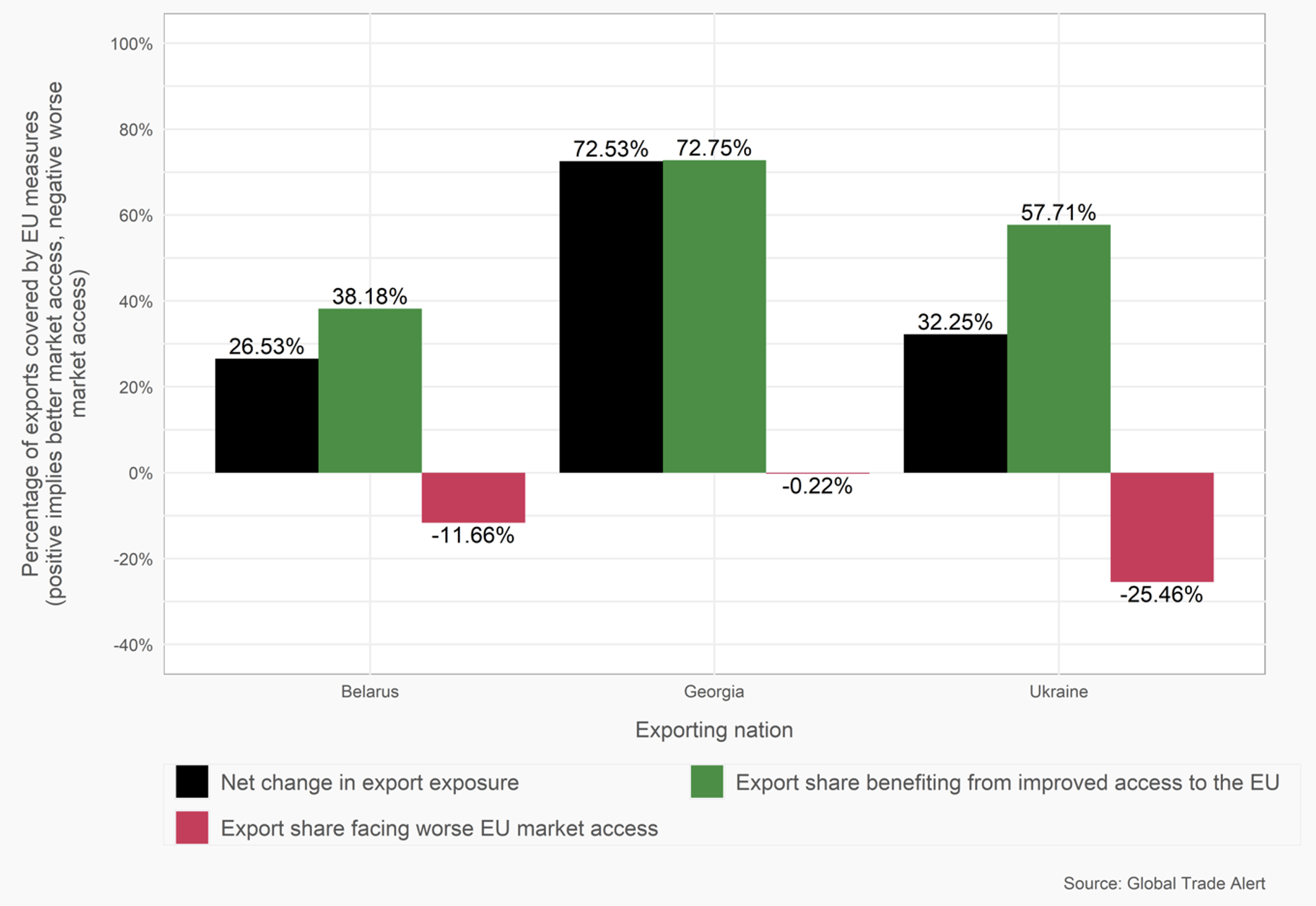

Figure 1 Since Crimea was annexed trade reforms by the EU cover 32 percentage points more of Ukrainian exports than trade restrictions

Figure 1 compares estimates of (a), (b), and (c) for Belarus, Georgia, and Ukraine, revealing these nations’ export exposure to EU import policy reforms and restrictions implemented after 1 January 2014 and still in force on 13 February 2022. In terms of (c), on net EU trade policy was supportive of Ukrainian export growth – EU trade reforms covered 57% of Ukraine’s exports, EU trade restrictions covered a quarter of Ukraine’s exports, leaving a net surplus of 32 percentage points.

EU unilateral trade policy actions affecting Ukraine are cast in a less favourable light when compared to the treatment of Belarus’ exports. Here the net favourable export exposure of Belarus to EU trade policy decisions was +26 percentage points. This implies that the Ukrainian beneficial export exposure premium over a country that is currently hosting Russian troops that threaten its sovereignty is just 6 percentage points. The contrast with Georgia is even more stark: hardly any Georgian exports are exposed to EU import restrictions imposed since 2014. Over 72% of Georgian exports are experiencing better market access on account of unilateral EU trade measures taken since the annexation of Crimea.

In sum, while more Ukrainian exporters have been exposed to EU trade reforms since 2014 than to EU import curbs, on net the improved potential market access just beats that of a Russian ally and is nowhere near the potential demonstrated by the Georgian case. In relative terms, EU commercial policy support in shoring up Ukraine has fallen short.

Soft versus hard power: The EU’s treatment of Ukraine compared to other Western nations

Western jurisdictions differ in the mix of “hard” and “soft” power they bring to bear when pursuing their foreign policy objectives. The EU does not have a tradition of deploying military forces and relies more on other instruments to advance its interests, including commercial policy. In contrast, the UK and US have deployed military forces on many occasions since World War II.9 Are these differences borne out in respect of Ukraine? The short answer is “yes”.

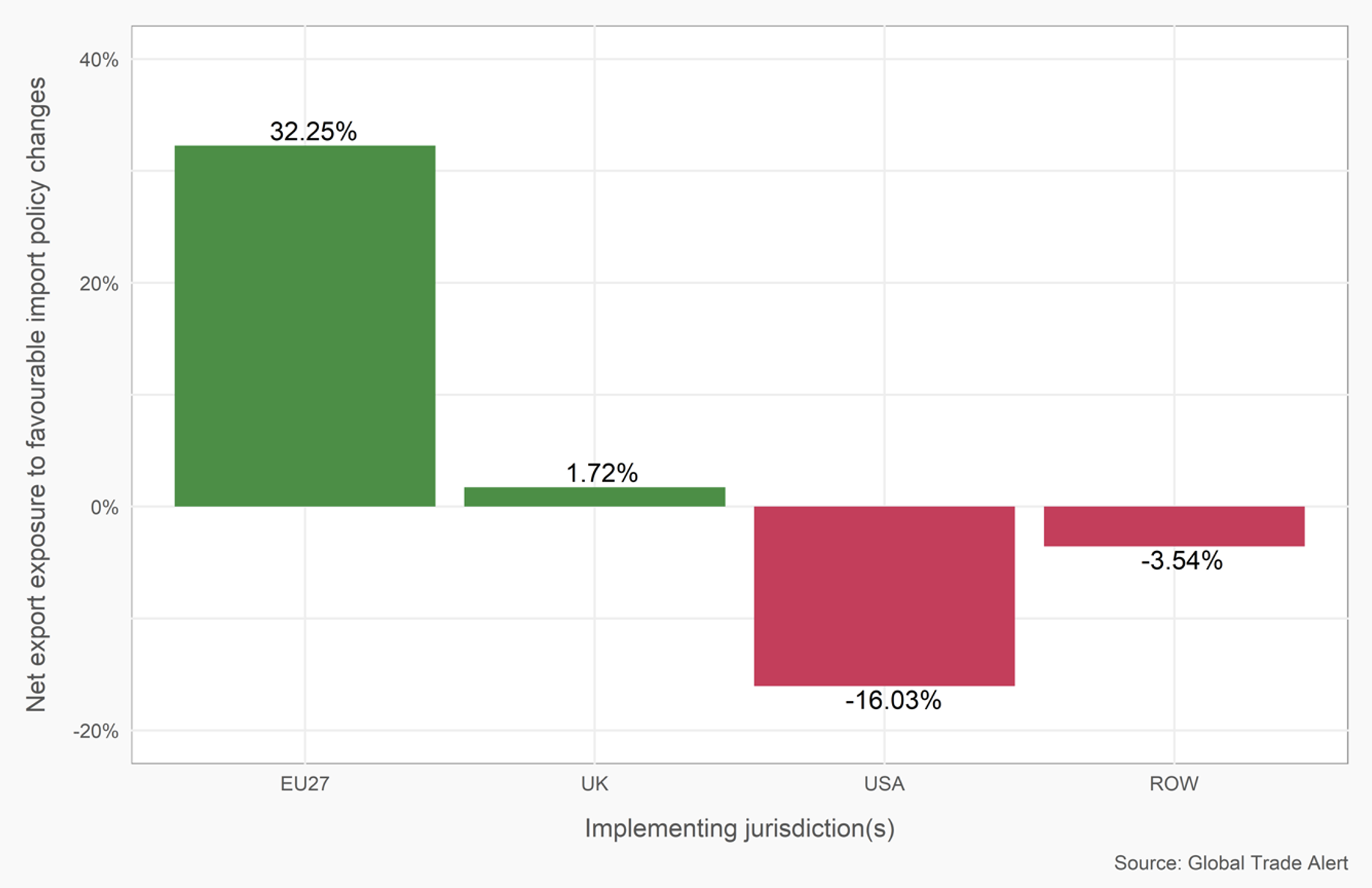

Figure 2 plots the net export exposure of Ukraine to the import policy changes of the EU, UK, US, and ROW. The rest of the world’s treatment of Ukraine’s exports deteriorated on net since 2014, with the percentage of that country’s exports facing new import restrictions exceeding that the percentage facing better market access by 3.5 percentage points. This provides a useful benchmark against which to compare the consequences of the EU, UK, and US’s unilateral import policy decisions.

The net deterioration of Ukraine’s access to the American market stands out in Figure 2. Since the invasion of Crimea new American import restrictions covered over 48% of Ukraine’s exports and less than a third (32%) of Ukrainian exports saw better access to the American market. It is worth noting that the period under analysis here (from 1 January 2014 to 13 February 2022) covers both the Trump and Biden administrations.

In contrast, EU and UK treatment of Ukrainian exports was more beneficial than the global average. The gap between better and worse treatment exceeded 5 percentage points of Ukrainian exports for British policy when benchmarked against the global average. Even more striking, however, is the degree to which EU policy was relatively more beneficial to Ukraine’s commercial interests than the Western governments used to projecting hard power.

Figure 2 Compared to other Western powers, EU trade policy has created more potential market access gains for Ukraine

Assessment

These findings should be seen in light of the longstanding cornerstone of the world trading system that international trade and peace are mutually reinforcing. Plenty of reasons have been advanced elsewhere linking these two outcomes, although inevitably there are some academic detractors. In the case of Ukraine, while only 5.5% of its exports go to Russia, even fewer of its exports go to the UK and the USA. Ukrainian exporter access to the latter markets has not improved much since the annexation of Crimea and in the case of the United States has most likely worsened.

Why does this matter in the present context? One feasible alternative to the UK and US arming the Ukraine now was to have supported that country’s economic growth over the past decade by granting better market access. In that way Ukraine’s exports would have increased, its economy grown, and greater tax revenues collected, some of which could have been devoted to higher defence spending. Of course, military and economic support need not be substitutes. However, assuming the objective was to give Ukraine the best fighting chance in the first place, this raises the question as to whether the Anglo-Saxon powers made the right strategic choices concerning their trade policies towards Ukraine once Russia revealed its hand by annexing Crimea.

In contrast to their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, EU import policy towards Ukraine has been more generous. For sure, there have been high profile EU-Ukraine initiatives, such as the Association Agreement. However, several subsequent unilateral EU commercial policy decisions have undercut this accord.

In this case, on net EU import policy changes since the annexation of Crimea favoured Ukraine’s exporters. But once unilateral policy decisions are taken into account and benchmarked against other nations in Russia’s near abroad, then the apparent EU generosity pales. The positive net change in market access conditions in the EU enjoyed by Ukraine is only slightly better than Belarus — a nation that is currently hosting Russian troops that threaten Ukraine’s sovereignty. According to Belarus’ WTO Trade Profile, 18.1% of Belarussian exports end up in the European Union. The EU may have leverage here but does not appear to have used it to any great effect.

The lesson here is that high profile bilateral accords are only one part of the trade policy landscape. A significant lesson from the Global Trade Alert’s decade long monitoring of trade policy is that unilateral policy decisions are often a critical part of the story and must be factored into overall assessments of trade policy stance. What a high-profile bilateral accord grants can be clawed back by unilateral trade policy acts,10 the cumulative impact of which is frequently overlooked and underestimated. All too often the bilateral and unilateral trade policy tracks operate in different worlds, so to speak, even in sophisticated trade policy actors such as the European Union.

The contrast in EU market access changes experienced by Ukraine and Georgia is remarkable and begs the question why the former could not have been treated as well as the latter. Here part of the answer may lie in the differences in the structure of Ukraine and Georgia’s exports. It is Ukraine’s misfortune that many of its exports are sensitive products in the West. For example, under a quarter of Georgia’s exports are agricultural goods—whereas over 45% of Ukraine’s exports are. Plus, Ukraine tries to export steel products to the West.

The deeper question, then, is how an importing nation seeking to shore up a trading partner with commercial policies can do so when the exports of the latter partner are politically sensitive in the former. Is there a limit to the degree to which traditional trade policies can deter war? Targeting market access benefits to products that are less sensitive is one answer, although multilateral trade norms probably prevent the most surgical fine-tuning. Maybe the growth of services, in particularly digitally delivered services, can be another means to shore up a trading partner.

In the absence of particularly supportive import policies, the emphasis on shoring up Ukraine may have to be on foreign direct investment and transfer of technology and managerial know-how. Development policy and initiatives by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development – in particular steps to make the national business environment more attractive — must play a role.

Should Ukraine survive its current travails in a meaningful form and should Western nations revisit the role that trade can play in deterring future conflict, then adopting a coherent mix of commercial policy support measures and sustaining that support is vital. Once the crisis passes unilateral commercial policy acts must not be allowed to undercut longer term plans to shore up a vulnerable country’s economy and its capacity to pay to defend itself. Incoherent policy by allies reduces the peace and regional stability dividend to buffer states, such as Ukraine.

In an era of growing geopolitical and regional rivalries, for the sake of buffer states around the globe future foreign policy-influenced trade policies must be better designed and executed if they are to advance the cause of peace more purposefully than was the case for Ukraine.

Endnotes

1 In this regard, it is worth noting that inflation-adjusted local currency terms, Ukraine’s total tax take did not return to 2013 levels until 2017, three years after the annexation of Crimea. Moreover, and germane to the argument developed in the main text, the real value of Ukraine’s total taxes collected peaked in 2008. As far as Ukraine’s military spending is concerned, the record is not entirely hopeless. Ukrainian military spendinggrew in real terms 8.8% per annum in the five years after the annexation of Crimea. This data was obtained from the World Development Indicators database maintained by the World Bank.

2 In fact, Ukraine hasn’t seen growth at all during the previous decade. According to the World Development Indicators database in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Ukrainian real GDP (measured in local currency terms) was 4% lower than in 2010. Real GDP in Ukraine was to fall further in 2020.

3 On 1 February 2022 the European Commission tabled another proposal for such assistance, amounting to 1,2 billion euros.

4 For the purpose of this analysis we took the EU as comprising its current 27 members.

5 Taken here to include all import tariff changes plus measures recorded in the Global Trade Alert database associated with United Nations MAST chapters D (contingent protection measures), E (non-automatic licenses, quotas, etc.), F (price control measures affecting imports and other tax measures), G (finance measures), I (trade-related investment measures), and M (government procurement restrictions). Notice that the award of subsidies to import-competing firms was not included in this analysis. The focus here is on changes in policies that reduce market access directly.

6 That is, the six-digit level of disaggregation in the COMTRADE database.

7 Consequently, trade policy measures that lapsed before 13 February 2022 do not count towards any of the totals reported here.

8 It being understood that this is only one way to assess the likely potential impact of the implementing nation’s trade policy decisions. Purists may prefer a full-blown econometric analysis of the effects of these trade policy changes. However, the counter argument is that there is likely to be little actual effect without much exporter exposure to the importing country’s reforms. In essence, net export exposure to market access improvements is likely to be a necessary condition for positive actual impact. Readers can judge whether investments in the latter are needed to make the conclusions ultimately drawn in this note.

9 That being so, no assumption is made here that the UK and USA would commit significant military resources to defense of Ukraine in the current standoff.

10 For example, in 2016 was it absolutely necessary for the European Commission to include Ukraine’s steel exports in an anti-dumping investigation against imports from that country, Brazil, Iran, Russia, and Serbia? Was the contribution of Ukraine’s steel exports really that threatening to the health of the EU steel sector?