Trump's steel and aluminum tariffs are cascading out of control

Chad Bown explains why the 'cascading protection' of the Trump administration's move to impose tariffs on even more steel and aluminium products is worrying.

Search the site

Chad Bown explains why the 'cascading protection' of the Trump administration's move to impose tariffs on even more steel and aluminium products is worrying.

President Donald Trump's brazen move in late January to extend his previously imposed "national security" tariffs on steel and aluminium to cover even more products was greeted with a collective yawn by many weary of his unending trade wars. But this latest action was significant because, explicitly for the first time, Trump was imposing new tariffs to help an industry suffering because of his previous tariffs.

Nearly two years earlier, Paul Czachor, CEO of American Keg Company, had warned that Trump's original tariffs would hurt companies like his and result in more protection of this sort. Czachor relied on so much steel that the cost increase driven by Trump's steel tariffs meant his company would no longer be price competitive with kegs made in Germany and Mexico, let alone China. At the time, Czachor predicted, "for finished product that has a high content of steel, we're going to need to see some help on those. Some tariffs."

On 24 January 2020, Trump delivered some of those tariffs for a handful of high-content steel products, including steel nails and car bumpers. While his new tariffs did not cover kegs, Trump implicitly acknowledged Czachor's concern by motivating his tariffs because imports of these sorts of high-content steel products had increased. But the increase in imports was due at least in part to American consumers of nails and bumpers switching to foreign suppliers to avoid paying for the American versions of products that Trump's tariffs had made more costly.

Economists refer to a second round of tariffs on products hurt by earlier duties as "cascading protection." These sorts of cascading barriers are worrisome for two other reasons aside from the economic impact of Trump's new tariffs.

First, the fact that Trump's latest action does not cover Czachor's kegs is immaterial. His kegs, as well as more than a dozen other products with a high content of steel and aluminium – covering ten times the amount of trade affected by Trump's latest tariffs – have triggered cascading protection since Trump's original tariffs went into effect in March 2018. Without waiting for Trump, Czachor got protection under a different US trade law called antidumping. Because antidumping duties have been far away from Trump's Twitter feed, the arrival of such protection has mostly gone unnoticed. But new data revealing the amount of this cascading protection arising under that law is troubling because its momentum may be difficult to stop.

Second, Trump's 24 January tariffs were unabashed, legally questionable, and came as an even bigger policy surprise than most of his other acts of protection. Despite his recent ceremonies celebrating the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and deals with Japan and China, Trump's tariff days appear far from over.

Trump extended his original 25% tariffs on steel and 10% tariffs on aluminium to four products that are "derivatives" of the metals (figure 1).1 Trump's additional protection is dominated by trade in bumpers ($231 million) and steel nails ($231 million); covered imports of aluminium wire ($15 million) and body stampings ($2 million) are much smaller.

Trump's new national security tariffs mostly hit imports from allies such as Taiwan, Japan, and the EU, as well as China. In keeping with the evolving structure of Trump's protection on steel and aluminium, imports from Australia, Canada, and Mexico would be exempted.2 Economically, the country-level exemptions are important. In 2017, the US imported more bumpers from exempted countries, for example, than from those targeted by the new protection.

Given the language of the annexes to the Federal Register notice, Argentina (derivatives of steel and aluminium), as well as Brazil and South Korea (derivatives of steel only) appear subject to quotas, or volume limits, and not tariffs. That is the structure that was agreed with these countries for the protection they faced in the original set of steel and aluminium products.

In trade terms, this announcement is small: the new tariffs and quotas on derivative products cover only $479 million, or 0.02% of total US imports in 2017. The new tariffs cover less than 1% of the amount of trade that Trump targeted with his original steel and aluminium protection in 2018. And it certainly pales in comparison to Trump's tariffs on $360 billion of Chinese imports.

The policy concern is separate evidence of the arrival of what economists feared. Trump's protection on inputs begets more protection on outputs.

The only positive to come out of Trump's bald-faced extension of his national security tariffs is that it refocused public attention to concerns of cascading protection. As Czachor originally described in March 2018, this sort of trade protection was coming "not across the board but specific industries that are harmed by this and also have import competition using low-cost steel."

The only question was when and how much. By September 2018, Czachor had put together his formal request for protection from less costly steel keg imports under US antidumping law. Within months, new tariffs of up to 80% were in place.

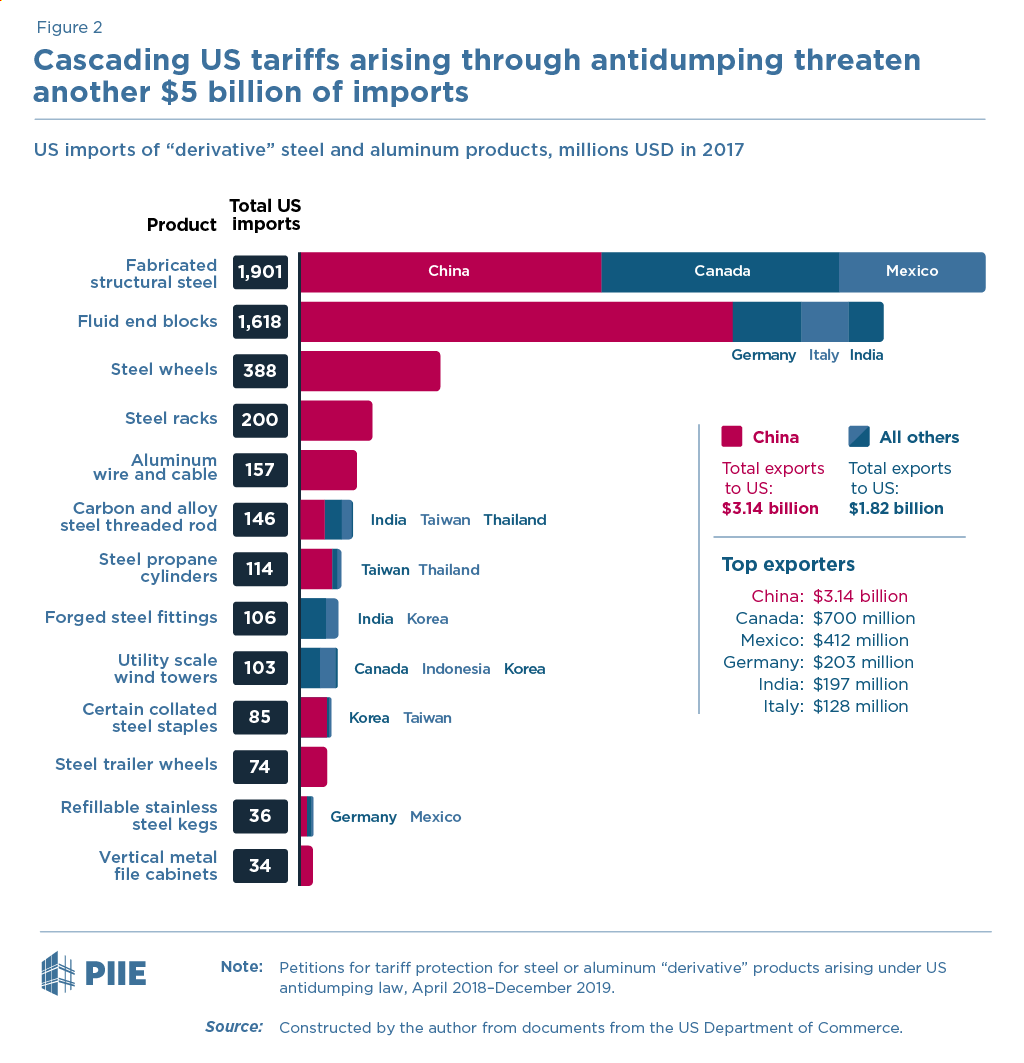

And Czachor's steel kegs were not alone. By the end of 2019, an additional $5 billion of US imports of steel and aluminium "derivative" products faced antidumping duties. In less than two years since Trump's steel and aluminium tariffs first went into effect, American manufactures of metal file cabinets, propane cylinders, wheels, wind towers, and loads of other products have all faced higher input costs and demanded new protection (figure 2).

That Trump's metal tariffs would hurt so many American companies making steel-derivative products was expected. Lydia Cox and Kadee Russ estimated 80 Americans work in the steel-using industry for every one employed in steel production. The cascade of additional protection was also not surprising, given economic research that input duties trigger knock-on tariffs on products that use those inputs.3

More worrying is that the potential antidumping duties on these additional $5 billion of imports of steel and aluminium derivative products are just the beginning. Trump's tariffs on $360 billion of imports from China also disproportionately targeted parts, components, and other inputs that American companies and workers require to remain competitive with firms in Europe, Japan, Canada, and elsewhere.

Despite Trump's phase one deal with China, all of those tariffs remain. Expect more cascading protection to arise on "derivatives" of those imported inputs from China as well.

Trump's new method of extending his steel and aluminium tariffs raises a host of separate worries.

The first is the possibility of corruption. How did the Trump administration choose these particular products for additional protection? They were not part of the original Section 232 study, and it is hard to justify imports of nails or car bumpers as legitimate threats to US national security. Did American companies ask for it? Did other companies also put in a request that was denied?

The Office of the Inspector General in the US Department of Commerce had already voiced public concern over misconduct by Trump administration officials. In October 2019, it found that "certain communications by department officials suggest improper influence in the Section 232 exclusion request review process," raising more questions about an already abstruse and ad hoc procedure for deciding which Americans get hit with tariffs.

In the lead-up to Trump's 24 January announcement, there was not even a hint that such tariffs were in the offing. No public hearing meant the administration failed to allow for possible counterarguments by those Americans who would be hurt by their protection. Even compared with the Trump administration's poor prior record on transparency for tariff actions, this time was different.

A second concern involves this policy's costs. American construction companies reliant on steel nails and automakers buying steel bumpers were hit with a sudden and unavoidable cost shock. The proclamation regarding these new products was made on 24 January, with tariffs going into effect on 8 February. Within two weeks, they would have to come up with an additional 25% of the costs of orders placed months before, some of which may have already been in transit.

This latest action is certain to reinforce the increased uncertainty that companies face in light of Trump's approach to trade policy. American companies are holding off investment, unsure whether the inputs they rely on will be available even two weeks hence – or if the foreign markets to which they export will remain profitable – due to the arbitrary nature of Trump's policy.

Third, such actions could threaten to undermine Trump's other deals. Trump's recent trade agreement with Japan included a joint statement that "both nations will refrain from taking measures against the spirit of these agreements and this Joint Statement." While Trump's tariffs certainly seem against the spirit of the deal, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe apparently decided it was not worth throwing away the entire agreement for $61 million of Japanese exports subject to new tariffs. But what if Trump's tariffs had hit an additional $1 billion of Japanese exports? Or $10 billion?

With each round of cascading tariffs, Trump has bullied more American companies into becoming protectionist. Against their will, he began by imposing tariffs that raised their costs by hitting their parts and components. When American companies were forced to beg to have their inputs excluded, his Commerce Department approved fewer than half of their requests.

For many Americans, the higher costs resulting from his tariffs mean they can no longer compete with foreign firms in either the US or global market. Aside from pulling up stakes and moving their plants abroad, there may be little they can do to remain competitive in foreign markets. But one last gasp remains for American companies seeking to survive in the US market. It will hurt American consumers, but they can switch to Trump's side, pleading that he also protect them from imports by raising costs on their foreign competitors.

The "Tariff Man" has imposed policies that are changing both the economy and America's political economy of protectionism. The worst may be yet to come.

DATA DISCLOSURE: The data underlying this analysis are available here.

1. The protection was imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which uses the terms "derivative steel articles" or "derivative aluminium articles" to refer to products that contain a lot of steel or aluminium content and thus derive from the metals that are used as a key input. Technically, the protection covers 13 Harmonized Tariff Schedule codes, but they group into four broadly defined products. To make the trade coverage statistics comparable with other trade war policy actions, the tariffs are matched with product-level US import data from 2017.

2. Australia was exempted from Trump's steel and aluminium tariffs from March 2018. Trump agreed to exempt Canada and Mexico on May 17, 2019, after they had both signed USMCA and announced they would remove the tariffs they had imposed in retaliation to his steel and aluminium duties.

3. See, for example, Aksel Erbahar and Yuan Zi, 2017, "Cascading Trade Protection: Evidence from the US," Journal of International Economics 108(C): 274–99.