First posted on:

Bank of England's Bank Underground blog, 8 August 2017

Financing World War I required the UK government to borrow the equivalent of a full year’s GDP. But its first effort to raise capital in the bond market was a spectacular failure. The 1914 War Loan raised less than a third of its £350m target and attracted only a very narrow set of investors. This failure and its subsequent cover-up has only recently come to light following research analysing the Bank’s ledgers. It reveals the shortfall was secretly plugged by the Bank, with funds registered individually under the names of the Chief Cashier and his deputy to hide their true origin. Keynes, one of a handful of officials in the know at the time, described the concealment as “a masterly manipulation”.

The emergence of capital markets as a war front

War was an expensive business. Between 1913/14 and 1918/19, government spending rose more than 12-fold to £2.37bn, almost entirely attributable to military expenditures (Morgan, 1952). While tax revenue did quadruple over the same period, war debt was required to finance the remainder. As a result, UK government debt increased from around 25% of GDP to 125% in four short years, requiring bond issuance and debt build-up on a pace unlike anything seen before (or since) in peacetime.

Figure 1 UK national debt

These unprecedented costs meant that war posed a fiscal as well as a military challenge for governments. Capital raising was not ancillary to Britain’s war strategy— as the wealthiest economy by far among the Entente, and the financial centre of its day, it lay at the heart of it. As articulated by Lloyd George in 1914, (Daunton, 2002; French, 1985) Britain’s plan was to use its commercial and military naval forces to ensure a blockade of the Central Powers, to provide a limited army to support French troops on the Continent and raise the capital to provide arms and supplies for its allies.

Although the government ostensibly appealed to investors’ sense of duty, they also offered an attractive yield on the bonds. For this first wartime foray into the bond market, the government offered 4.1%, well above the 2.5% payable on other government debt at the time. Unlike almost all existing government debt, which took the form of consols, war bonds were loans where principal was to be repaid after 10 years.

As part of a project looking at the financing of World War I, the ledgers of investors who purchased the 3½% War Loan have been analysed for the first time. These reveal the startling truth about the failure of the first bond issue of the Great War and the extraordinary role of the Bank of England in covering and then concealing the shortfall in funds…

The disastrous first bond issue

Britain’s banks agreed initially to make firm offers for £60m of the new issue, representing up to 10 per cent of their deposit and credit accounts, while the Bank of England agreed to take up £39.4m. The remaining £250m was expected to be sold to the public. However, demand was so weak that only £91.1m was purchased.

And what funds were raised came from a woefully small group of financiers, companies and private individuals. These included wealthy private individuals and companies including what would become known as Bass Brewers and several shipping companies that were among businesses benefitting from surging war demand for their services (see images below).

Figure 2 Bond purchases by companies

The 1914 War Loan was sold in minimum lots of £100 to avoid drawing off deposits from Post Office Savings Banks where rates were much lower, which significantly narrowed the pool of potential investors. Just 1.2m individuals earned the £160 per year net of exemptions to require them to pay income tax (Daunton, 2002). Ranauld Michie, a historian of British investment, estimated that there were roughly 1m holders of tradable securities on the eve of World War I (Michie, 1999). The ledgers show that only 97,635 investors signed up to buy bonds, fewer than 10% of the pool of potential investors. Not only was the pool of wealth narrow and concentrated; it was heavily invested outside Britain where higher returns were found. An estimated £4bn was invested abroad in 1914, so only a fraction of these funds were voluntarily repatriated to finance the war effort.

Of those who did purchase, the modal investment was the minimum £100 and half of all investments were for £200 or less. But a small fraction of 2% of investors by number accounted for over 40% of investment by value.

Figure 3 Average value of War Loan holdings by region

Figure 4 Percentage of households purchasing War Loans by region

These were disproportionately based in what was unquestionably the world’s financial capital, the City of London, suggesting the vulnerability of Britain’s economy as a whole to the exigencies of war.

The highest percentage of households buying War Loan was concentrated in London, with the second highest in the wealthy South East of England. However, in the rapidly industrialising West Midlands, a smaller percentage of households bought the bonds, but those households had deeper pockets; sums raised there were higher than in the South East.

The great cover up

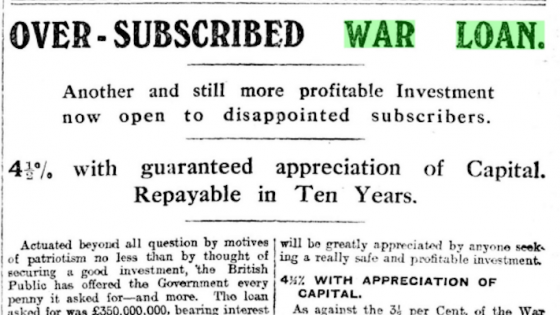

The general public could be forgiven for believing that the first War Loan was an unbridled success, given the overwhelmingly positive coverage. The Financial Times, for example, reported on 23 November 1914, that the Loan had been over-subscribed by £250,000,000. “And still the applications are pouring in,” it gushed.

Figure 5 Financial Times cutting

Source: Financial Times, 23 November 1914. Reproduced by kind permission of the Financial Times

Disclosure of the failed fund raising would have been “disastrous” in the words of John Osborne, a part-time secretary to Governor Montagu Norman, in a history of the war years written in 1926. Copies of this account were only given to the Bank’s top three officials and it was decades before the full version emerged. Revealing the truth would doubtless have led to the collapse of all outstanding War Loan prices, endangering any future capital raising. Apart from the need to plug the funding shortfall, any failure would have been a propaganda coup for Germany.

So to cover its tracks, the Bank made advances to its chief cashier, Gordon Nairn, and his deputy, Ernest Harvey, who then purchased the securities in their own names with the bonds then held by the Bank of England on its balance sheet. To hide the fact that the Bank was forced to step in, the bonds were classified as holdings of ‘Other Securities’ in the Bank of England’s balance sheet rather than as holdings of Government Securities (Wormell, 2000).

John Maynard Keynes, in a 1915 memo to Treasury Secretary John Bradbury (below), which was stamped ‘Secret’ -, praised the ‘masterful manipulation’ of the Bank’s balance sheet as means of hiding what would have been a damning admission of failure. But he also warned that Bank financing of the war should not be allowed to go on and that funds must be found elsewhere.

Figure 6 Keynes memo

Source: The National Archive (T170/72)

The longer term consequences

Faced with the possibility of catastrophic defeat, Britain threw overboard its centuries-long embrace of free market principles in several areas. It demonstrated a previously unseen willingness to interfere in private ownership of industry and property. It demanded that industries produce required goods, imposed rent freezes on private property, rationed imports and ultimately confiscated its own citizens’ foreign securities (Archive: 8A240/1).

Finance was no exception. Evidence from this sample of early investors in the War Loan illustrates that ‘sacrifice’ alone was not sufficient to attract the required funds. Subsequent war financings l would pay investors an even higher premium— including the mammoth War Loan of 1917 which raised £2bn by offering a hefty return of 5.4%.

But even this wasn’t enough. In January 1915, the Treasury prohibited the issue of any new private securities without clearance, and UK investors were banned from buying most new securities (Morgan (1952)). As the war dragged on, and capital became increasingly crucial to the Allies, the net would tighten further. And this episode was to be the first of several instances during the war where the Bank used its own reserves to provide needed capital.

The long-held laissez-faire principles of the Liberal and Conservative parties were thus sacrificed to raise the capital upon which the War’s outcome depended. Later on this would become a source of controversy. As the war unfolded, ministers were pilloried for rewarding investors far too generously for surrendering capital which should have been sacrificed gladly as a matter of patriotic principle (Hirst and Allen, 1926) . And during the 1920s, as debt service rose to nearly 40% of tax receipts, investors were cast as profiteers, idly collecting rents on War Loans while others toiled.

For the Bank of England and economic policymakers more generally, this early failure led to the realisation that managing the national debt was a complex and, in war times, perhaps Herculean task. The episode marked an important step on the Bank’s transformation from private institution to a central bank.. A decade after the Armistice, the altered role of the Bank prompted creation of a Parliamentary commission to examine its functions, ultimately setting it on a path to nationalisation (Sayers 1975).

Authors' note: We are grateful to the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council for supporting our research (Award Number AH/M006891/1).

References

Bank of England Archive – file 8A240/1

Daunton, M. (2002) Just Taxes: The Politics of Taxation in Britain 1914-1979, Cambridge University Press, p40, Table 2.2 p42

French, D. (1986), British Strategy and War Aims 1914-1916, (RLE First World War), Routledge

Hirst, F.W., Allen, J.E. (1926) British War Budgets, Humphrey, Milford, London, for Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,

Michie, R.C. (1999), The London Stock Exchange: A History, Oxford University Press, p 71

Morgan, E.V. (1952) Studies in British Financial Policy 1914-25, Macmillan & Co, London p104 Table 9

Wormell, J. (2002), The Management of the Debt of the United Kingdom: 1900-1932, Routledge, London.

Sayers, R.S. (1975) The Bank of England 1891-1944, Vol. I., p66