The incoming UK government headed by Rishi Sunak put forth its first budget in its November 17 Autumn Statement. This followed a turbulent month of failed budgets, U-turns, soaring gilt yields, and cracks showing in the UK’s financial stability. With the impression that the previous government’s crisis was triggered by irresponsible budgetary policies, the Autumn Statement naturally centred on fiscal rectitude. The budget made efforts to address head-on the ‘black hole’ in the UK’s public finances that was estimated to be as large as £50 billion. The dire state of public finances contrasts with the UK’s fiscal condition earlier this year, with the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicting that the government was on track to hit both of its fiscal targets with £30 billion of ‘headroom’ to spare in March 2022 (Joel 2022).

High fiscal spending to mitigate the effects of the cost-of-living crisis has put considerable pressure on government finances, threatening an ever-rising trajectory of underlying debt in the absence of appropriate policy action (OBR 2022). While similar problems have affected other European countries, certain UK-specific factors have raised borrowing costs relatively more than other advanced economies. These include short-term issues like the infamous September mini-budget, which is estimated to have been responsible for about £30bn of the fiscal hole, and long-term factors such as Brexit.

The Autumn Statement included a fiscal consolidation package of £55 billion of higher taxes and public spending cuts. Much of the tax revenue will be raised by freezing tax thresholds in the face of higher inflation until 2028, lowering the income threshold facing the 45% tax rate, and a windfall tax on energy companies and energy generators. All departments other than the protected health and education departments will face lower growth in their budgets than previously planned. Alongside these deficit-reduction policies, the budget loosened the UK’s fiscal rules allowing a slower pace of deficit reduction (Institute for Government 2022). Under the new rules, debt will be on course to fall in the fifth year (2027/28), rather than the three-year timeframe in previous rules. In accordance with the new rules, most of the tightening in fiscal policy is back-loaded, coming into effect in the last three years of the five-year planning period – after the next UK general election (Adam et al. 2022).

Reactions to the Autumn Statement have been mixed across experts and think tanks. The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), which first rung alarm bells by claiming that there was a £62 billion hole in the UK’s finances (IFS 2022), commended Hunt’s fiscal tightening measures as “a belated recognition of harsh realities” (Adam et al. 2022). The IFS recognised Hunt’s choice of backloading the tightening measures as the right one, given the great degree of uncertainty and high costs of a large up-front fiscal tightening. However, they questioned the credibility of the government’s plans, given that they had delayed most of the harsher tightening measures till after the next general election. The EY ITEM Club echoed these thoughts, claiming that the “threat to the economy from tighter fiscal policy isn’t as great as it could have been”, but simultaneously questioned whether some of the harsher measures would be enacted in the future. Other organisations, such as the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) (Mosley and Pabst 2022), the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS 2022), and the Policy Exchange (MacDonald 2022), also labelled Hunt’s response as sensible and prudent from a fiscal tightening perspective. However, they also stressed the need for the government to devise long-term plans to boost growth and productivity levels in the UK. The IMF also commended the budget for striking “the right balance between fiscal responsibility and protecting growth and vulnerable households” (Martin 2022).

While there is near-unanimous agreement on the precarious state of the UK economy, leading to fiscal pressures, several commentators have questioned the size, and even the existence, of the UK’s fiscal black hole. The Institute for Public Policy Research’s Centre for Economic Justice argued that reducing public spending and harming growth prospects to close a hole of the government’s own creation was a "short-sighted" move. The Adam Smith Institute and the Institute of Economic Affairs characterised the measures as a recipe for "managed decline", due to their detrimental effect on people’s after-tax income, and criticised the government for their lack of pro-growth reform.

Some economists argue that the fiscal black hole inherently depends on the set of fiscal rules that the government chooses to follow, and as such, is simply the consequence of a set of arbitrary rules (Whelan 2022). The May 2021 CfM survey found that the expert panel was nearly unanimous in agreeing that the existing EU fiscal rules required revision (Ilzetzki 2021a). Furthermore, the October 2021 CfM survey found that nearly a third of the expert panel supported the scrapping of fiscal rules, claiming that they harmed macroeconomic policy more than they helped, although the survey was held last year – well before the recent fiscal crisis (Ilzetzki 2021b). Several academics have also questioned the targets set by fiscal rules, describing them as “arbitrary”, and “relying on special ‘magic numbers’ for debt or deficit levels”. In a recent Vox column, Leandro et al. (2021) characterised the fiscal rules in the EU as “a crude and unsatisfactory assessment of debt sustainability”, and proposed replacing them with fiscal standards. Chadha et al. (2021) propose rethinking fiscal rules, emphasising the need for greater parliamentary and academic scrutiny, clear objectives and a stronger focus on social welfare and productivity. Furthermore, some organisations have criticised the government for the measure of debt used to assess the size of the hole. The Progressive Economy Forum found that small changes in forecasts for future interest rates and growth, and what is counted as government debt, dramatically alter the size of the predicted gap in the public finances.

Other criticisms included questioning the feasibility of the government’s public spending cuts, as they would require years of holding down public sector wages relative to the private sector (Bell et al. 2022). The Institute for Government also claimed that while the new set of fiscal rules introduced are “permissive”, there is only a small margin for error against the rules, meaning any further deterioration of the forecast could necessitate additional action next year. The Labour Party has also criticised the government for “ for a potential Labour government in the future, given that the new government would have to implement most of the harsh tightening measures, which would significantly affect its popularity.

This month’s CfM survey asked the members of its UK panel about the need for fiscal consolidation in the UK. They were first asked whether the UK had a fiscal gap that needed to be filled with higher taxes or spending cuts. They were then asked whether the measures taken by the government go far enough or too far in addressing the government’s financing needs. Finally, they were asked about the mix between public spending cuts and tax increases in the budget.

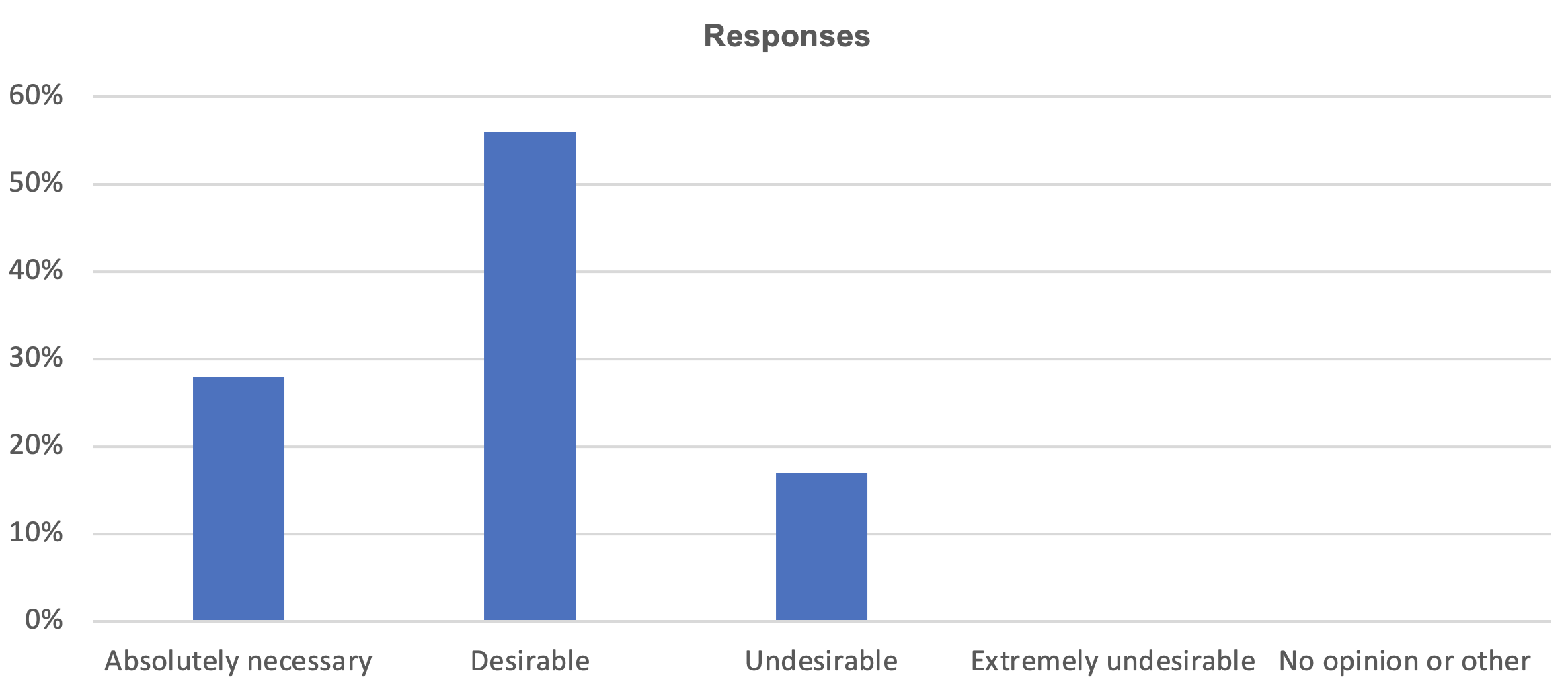

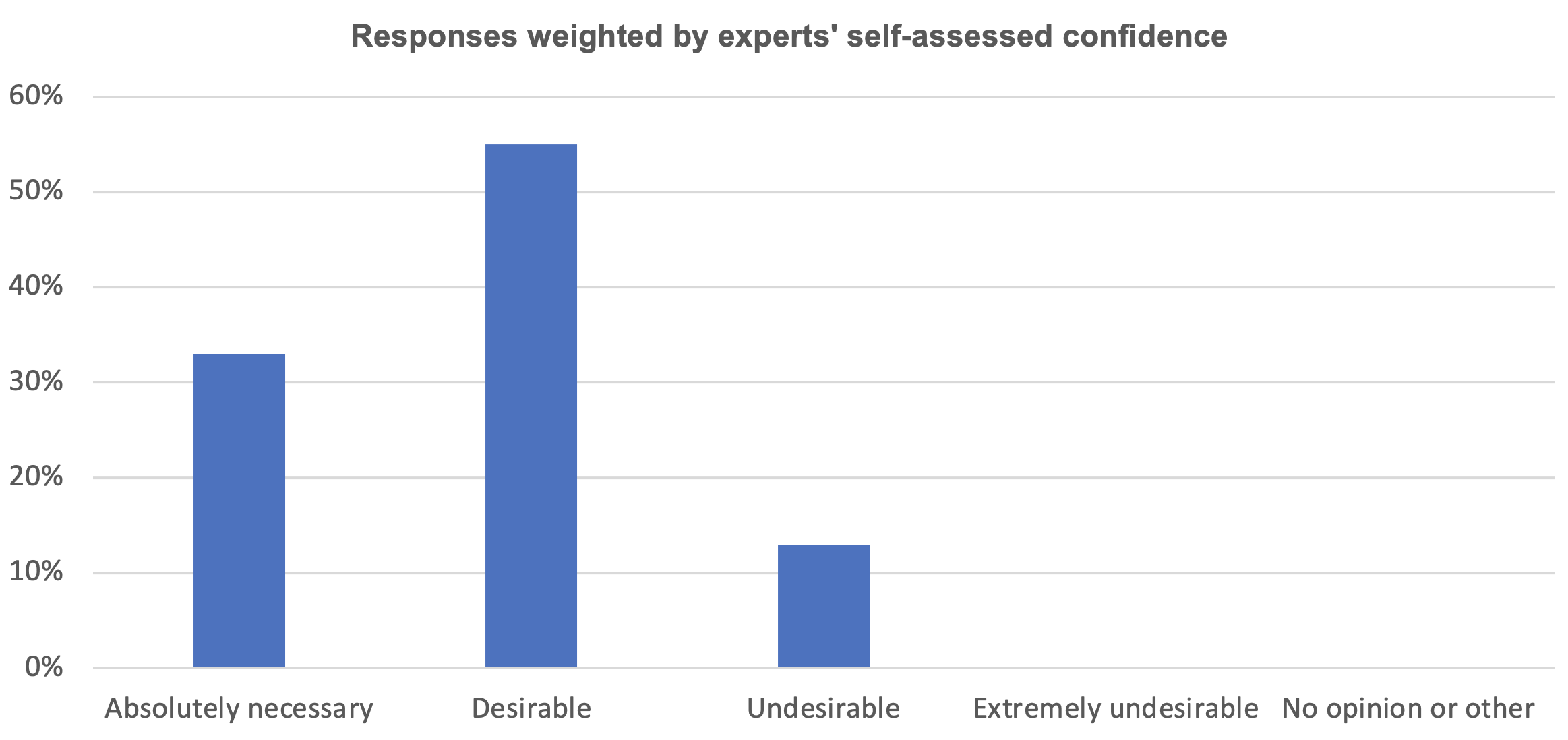

Question 1: How necessary was it for the UK government to lower its deficit through tax increases or spending cuts in November 2022?

Eighteen panel members responded to this question. There was near unanimity supporting the need for deficit reduction, with 56% believing deficit reduction was desirable and an additional 28% thinking it was absolutely necessary. Only 17% thought that deficit reductions were undesirable.

Most panellists feel that deficit reduction is important to restore the credibility of the government following the September mini-budget crisis. Martin Ellison (University of Oxford) summarised this, stating that “a show of fiscal responsibility was necessary to start the slow and painful process of rebuilding the government's reputation.” Ricardo Reis (London School of Economics) seconded this view, claiming that any “sensible fiscal reaction function [of the UK government] would have some policy change towards lowering deficits.” Panellists also stressed the need to ensure fiscal spending was sustainable in the long run, with Sir Charles Bean (London School of Economics) pointing towards the deterioration of the government’s medium-term fiscal position on account of “the global rise in short and long-term interest rates and the associated increase in debt interest.” He notes that the government needed a “a credible plan to lower its medium-term deficit in order to bring the public finances back onto a sustainable path.”

A few panellists disagreed with the government’s measures, characterising the Autumn Statement as going “too far” and “overcompensating” for the September mini-budget. Roger Farmer (University of Warwick) argued that “moderate deficits are sustainable [in the] long term and large deficits are possible in times of crisis,” adding that the current crisis did qualify as one of these instances. Some panellists were also worried about the effect of these measures on the already-stunted UK economy. Wouter Den Haan (London School of Economics) highlighted that “another round of austerity is likely to negatively affect productivity (e.g. because of insufficient NHS funding) and economic growth.”

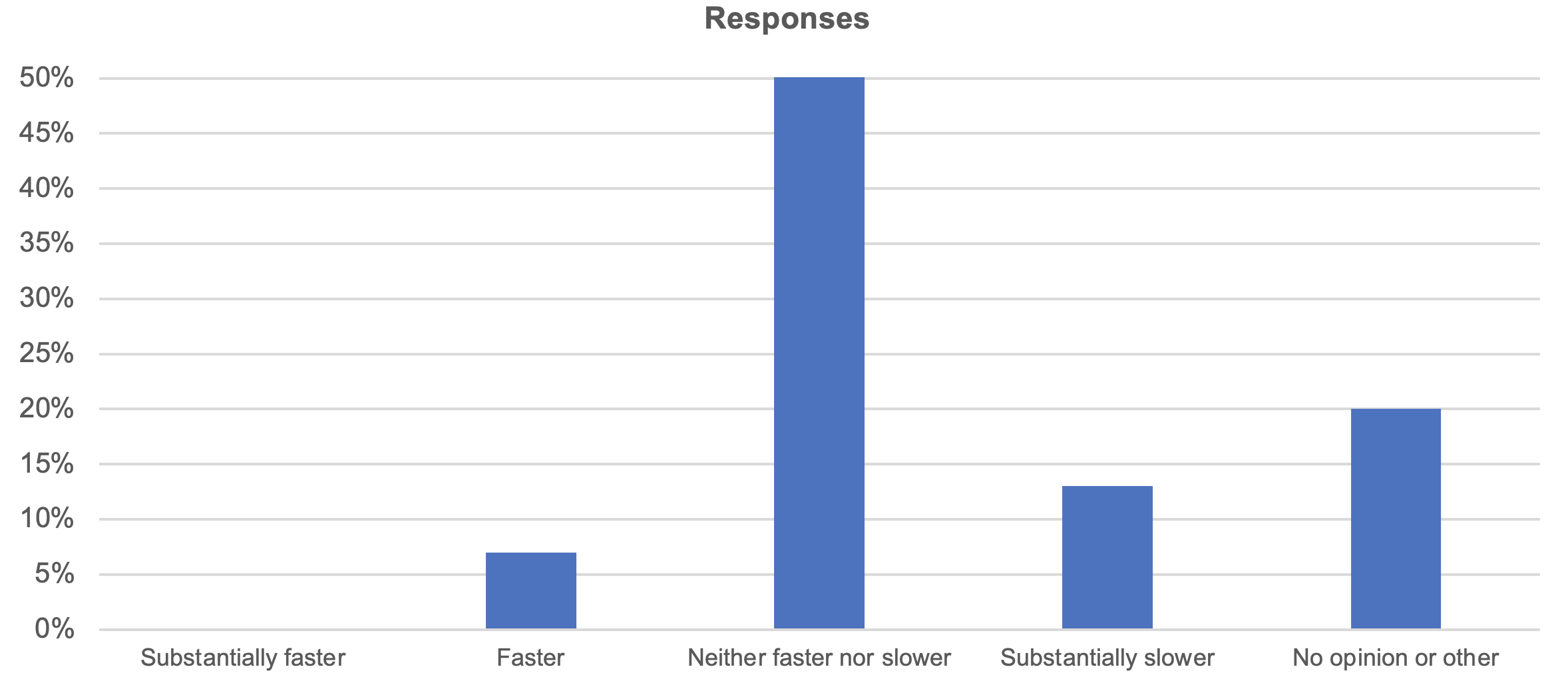

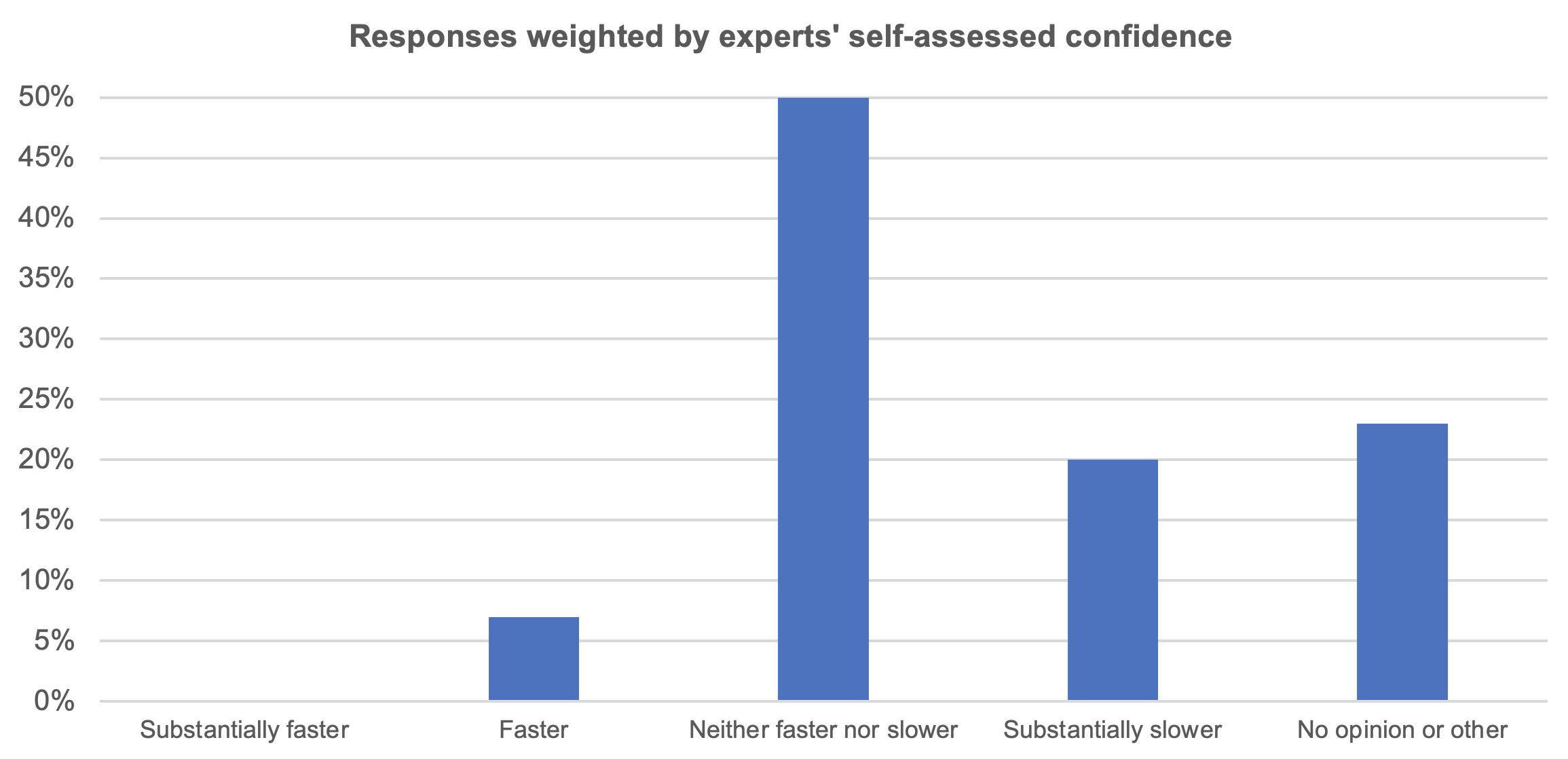

Question 2: On balance, relative to the Autumn statement, would it be better for the UK to reduce public debt faster or slower?

Fifteen panel members responded to this question. A majority of 60% of the panel endorsed the pace of deficit reduction in the budget. Thirteen percent of the panel would have liked to see a slower pace, and 7% a faster pace of deficit reduction.

Several panellists supported the current pace of deficit reduction but emphasised the potential need for adjustments in the future to ensure fiscal consolidation in a reasonable timeframe. This view is summed up by Sir Charles Bean: “The present speed of planned consolidation strikes a reasonable balance between providing near-term support to the economy and getting the public finances onto a sustainable trajectory further out.” He added that should economic conditions improve in the future, the government should “bank the surprise as a faster pace of consolidation,” instead of taxing less or spending more. Echoing these sentiments, Martin Ellison supported the “the back-loading of fiscal consolidation and an almost glacial paydown of the debt,” but urged the UK government “to demonstrate commitment to reducing the debt in a reasonable timeframe” to restore its credibility.

However, a small fraction of the panellists felt that the costs of decreased growth, productivity and economic welfare were too high to justify the proposed pace of debt reduction. Stephen Millard (National Institute of Economic and Social Research) advocated for a substantially slower pace, stressing that “the need at the moment is to loosen fiscal policy so as to help struggling households deal with the cost-of-living crisis.” Michael Wickens (Cardiff Business School & University of York) argued that given the UK’s lower debt-GDP ratio than Germany and the US, and the fact that the UK “has never defaulted on its debt”, market concerns about a slow pace of debt reduction would be unwarranted. He added that as “the debt-GDP ratio is already falling due negative real interest rates”, “fiscal austerity just reduces growth and economic welfare.”

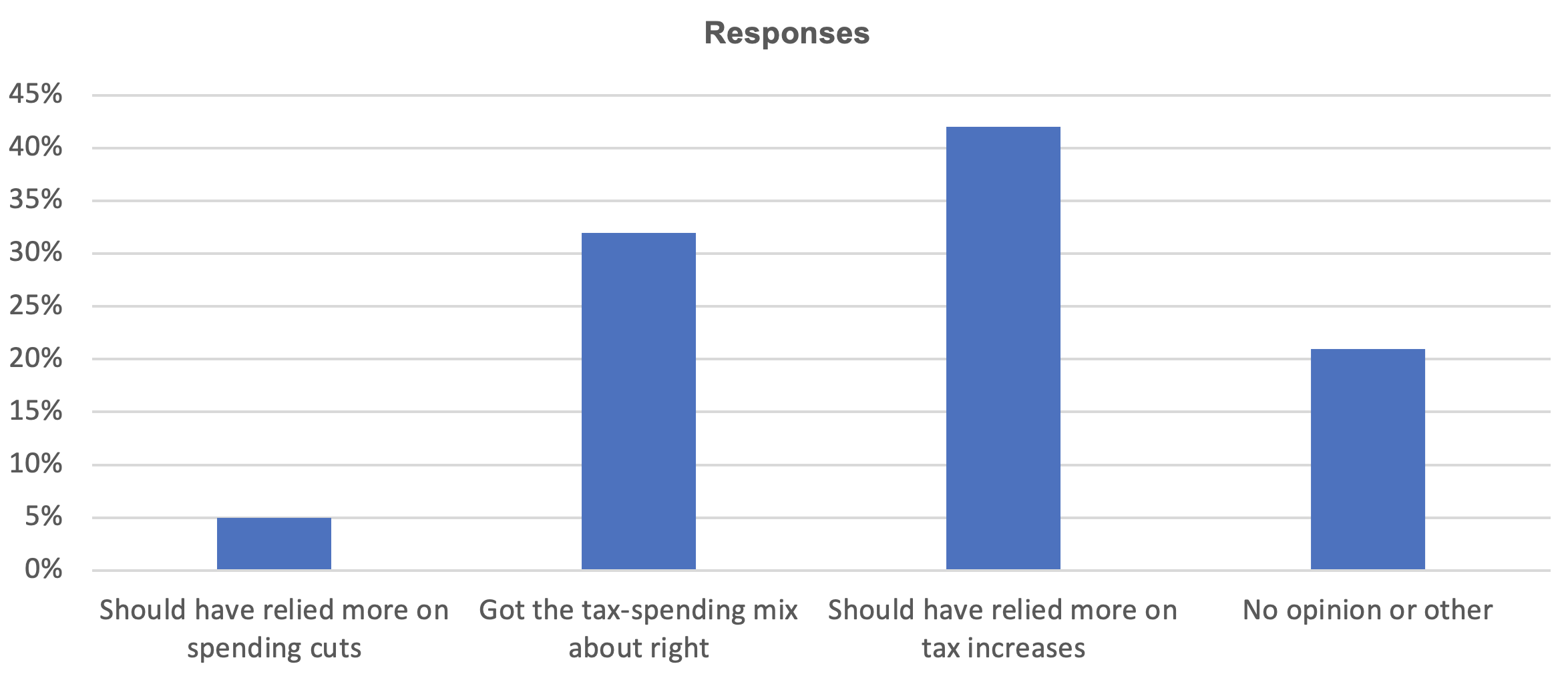

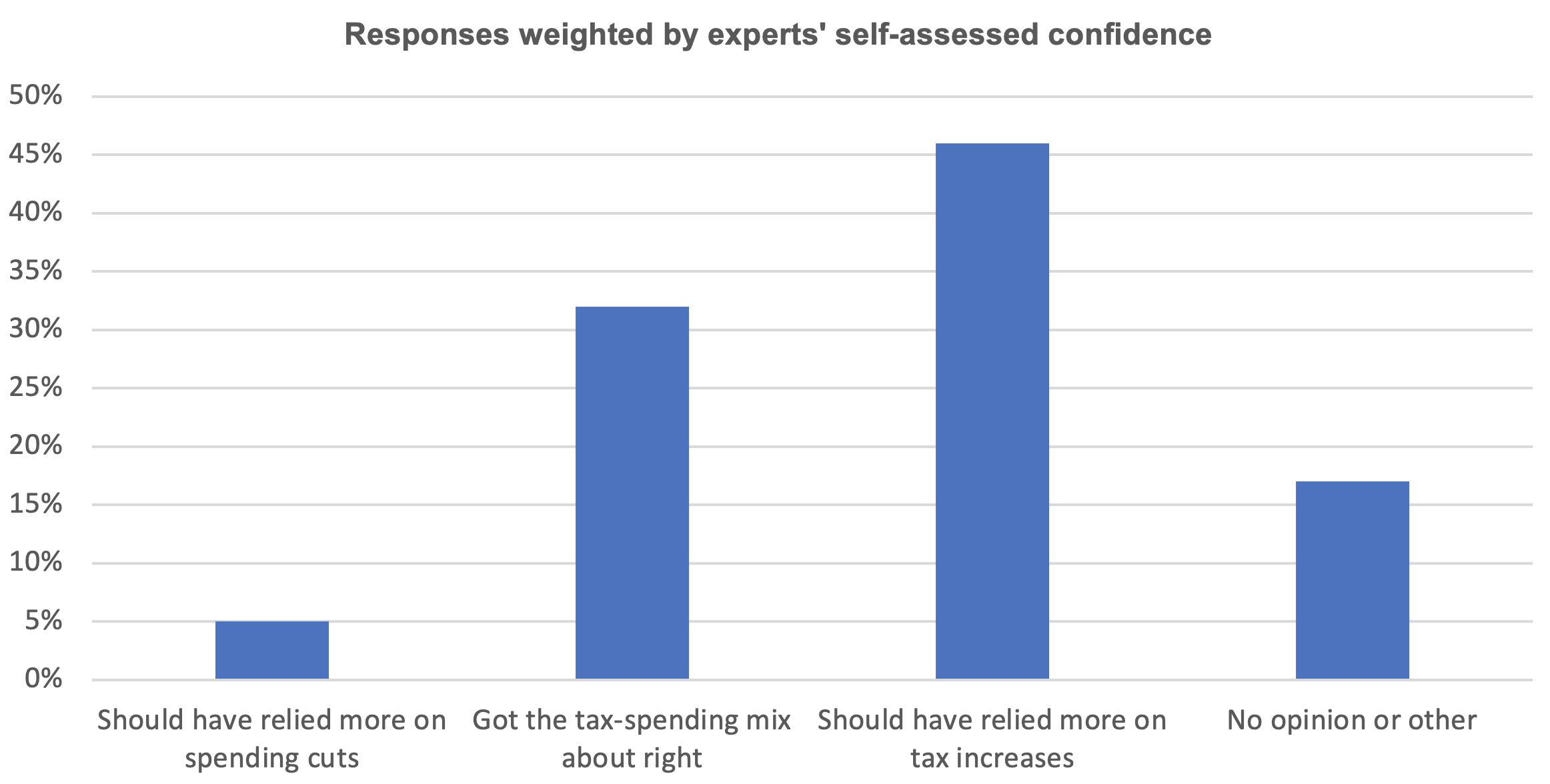

Question 3: Given the desired amount of deficit reduction, should the Autumn Statement have, on balance, relied more on a greater reduction in public spending reduction or more tax increases?

Nineteen panel members responded to this question. Forty-two percent of panellists thought the deficit reduction should have relied more on tax cuts compared to only 5% (one panellist), who would have liked to see more public spending cuts. Thirty-two percent of the panel believes the government’s tax-spending balance was about right.

A sizeable proportion of the panellists questioned the government’s greater reliance on spending cuts given that – as put by Stephen Millard – “public services have already been cut to the bone.” Martin Ellison doubted the government’s ability to deliver the proposed cuts as they “relate to essential services that people expect to be provided.” He pointed to the trade-off between the cost and quality of public services, claiming that “it is not possible to repress public sector wages without severe cuts in the quality of services provided across many government departments.” This point was reiterated by Sir Charles Bean: “The departmental spending plans require either a further reduction in the public sector pay relative to that of the private sector, which will create significant recruitment and retention problems, or an unacceptable deterioration in the quantity and quality of public services delivered.”

Ricardo Reis expressed contrary views, arguing for greater reliance on spending cuts instead of tax hikes. He advocated reducing fiscal spending rather than increasing taxation because “tax revenues/GDP already increased by 1.4% between 2020 and 2021 in the UK, versus only 0.5% in the OECD average.”

However, some panellists felt the government had got the tax-spending balance right and supported the back-loading of contractionary measures. Jumana Saleheen (Vanguard Asset Management) described the tough trade-off the government had to manage: “They had to walk the tightrope between (a) convincing markets they were fiscally prudent and (b) not hurt growth excessively through austerity at a time of rapid monetary policy tightening.” She expresses her support for the government’s plan, adding that “they did a good job at providing short-term stimulus to the economy and convincing markets of their medium-term fiscal orthodoxy.”

A few panellists also believed that the discussion surrounding the tax-spending balance should not be restricted to just the balance between the two but the type of tax hikes and spending cuts. Roger Farmer summarised this view: “It's not just a question of tax increases or spending cuts. It matters a lot which taxes are increased and which expenditures are cut.”

References

Adam, S, C Emmerson, P Johnson, R Joyce, H Karjalainen, P Levell, I Stockton, T Waters, T Wernham, X Xu and B Zaranko (2022), “An initial response to the Autumn Statement from the IFS”, IFS Report.

Bell, T, M Brewer, M Broome, N Cominetti, A Corlett, E Fry, S Hale, K Handscomb, J Leslie, J Marshall, C McCurdy, K Shah, J Smith, G Thwaites and L Try (2022), “Help today, squeeze tomorrow: Putting the 2022 Autumn Statement in context”, Resolution Foundation Briefing.

Centre for Policy Studies (2022), “Autumn Statement Response: Hunt wields the scalpel, not the axe”.

Chadha, J S, H Küçük, and A Pabst (eds), (2021), “Designing a new fiscal framework: Understanding and Confronting Uncertainty”, National Institute of Economic and Social Research Occasional Paper LXI.

Emmerson, C and I Stockton, (2021), “Outlook for the public finances”, IFS Report R220.

Ilzetzki, E, (2021a), “Fiscal rules in the European Monetary Union”, VoxEU.org, 10 June.

Ilzetzki, E, (2021b), “The UK’s post-Covid fiscal rules”, VoxEU.org, 11 November.

Institute for Fiscal Studies (2022), “IFS Green Budget 2022”, IFS Report.

Institute for Government (2022), “Five things we learnt from Jeremy Hunt's 2022 autumn statement”.

Joel Hills (2022), “The fiscal black hole: How did we end up here?”, ITVX insight.

Leandro, Á, J Zettelmeyer and O Blanchard (2021), “Ditch the EU’s fiscal rules; develop fiscal standards instead”, VoxEU.org, 22 April.

MacDonald, C (2022), “A Necessary Response to Crisis, but Not a Long-Term Vision”, Policy Exchange.

Martin, E (2022), “IMF Applauds UK’s New Fiscal Plan After Rebuking Previous One”, Bloomberg UK.

Mosley, M and A Pabst (2022), “Evaluating the 2022 Autumn Statement”, National Institute of Economic and Social Research Blogs.

Office for Budget Responsibility (2022), “November 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook Transcript of Presentation by: Richard Hughes, Chair, Office for Budget Responsibility”, 17 November.

Whelan, K, (2022), “On the UK’s Fiscal Black Hole”, karlwhelan.com, 14 November.

Wren-Lewis, S, (2022), “Missing a fiscal rule does not make a black hole, and a financial crisis after tax cuts does not mean markets want spending cuts”, mainlymacroblogspot.com, 15 November.