Corporate ownership matters, even in China. There is a well-established difference of behavior between private-sector firms and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), if only because the former are driven to a much greater extent by the objective of profit maximization, resulting in greater productivity gains (Lardy 2014, Lardy 2019). The pervasive presence of the Chinese Communist Party, and its determination to control some aspects of the behavior of even private-sector companies – for example, in terms of censorship and access of the security services to data – does not offset the significance of that divide. It is thus important to seek an accurate picture of the respective shares of the private and of the state sector in China, as it is in other jurisdictions (Büge et al 2013, Abate 2020).

In our research on the largest companies in China (Huang and Véron 2022), we collected and analyzed data on the changing shares of the state sector and the private sector among China's largest companies for more than a decade. The data show that China's private sector has grown not only in absolute terms but also as a proportion of the country's largest companies, measured by revenue or (for listed ones) by market value, from a very low level when President Xi was confirmed as the next top leader in 2010 to a significant share today. SOEs still dominate among the largest companies by revenue, but their preeminence is eroding. The Chinese idiom "the state advances, the private sector retreats," which has been widely used to describe China's economic trends does not, therefore, represent the main picture of what has been going on under President Xi in China's business world so far, even in recent years.

Rapid rise of private sector among China's largest companies

Unlike in many other countries, China's largest companies are often not listed on a stock exchange. That is the case for both the state sector and the private sector, even though many unlisted SOEs have much of their activity conducted in majority-owned listed subsidiaries. Thus, we examine both listed and unlisted companies, using two partly overlapping rankings of China's largest companies.

The first sample is ranked by revenue, a proxy for a company's activity. We use data compiled by the business magazine Fortune for its yearly Fortune Global 500 ranking, from which the paper extracts the companies from mainland China. This group has grown fast, from 15 companies in the 2005 ranking (based on 2004 revenue) to 130 in the 2021 ranking (based on 2020 revenue). Their aggregate revenue grew from $2.8 trillion in 2010 to $8.8 trillion in 2020. Their aggregate headcount was 21 million in 2020, slightly under a twentieth of China's total urban employment, a ratio that has been fairly stable over the past decade.

The second sample is limited to mainland Chinese companies whose shares are listed on a stock exchange, whether in Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and/or New York, including companies like Alibaba and Tencent that have adopted variable-interest-entity arrangements to circumvent China's onerous regulations on foreign ownership in certain sectors such as internet services. We constructed yearly rankings of the top 100 Chinese listed companies by year-end market capitalization, from 2010 through 2021. Their aggregate headcount and revenue levels are significantly lower than those of the first sample, as would be expected since they do not include some gigantic yet unprofitable unlisted SOEs, and conversely they include some high-growth young companies that hold much promise but are still relatively small. Together, these largest 100 listed companies represent about two-fifths of the entire market capitalization of all Chinese listed companies.

The ownership of these largest Chinese companies involves a range of investor categories. These include, among others, the Chinese state at the central and local levels, directly through government ministries or departments (such as the Ministry of Finance of the central government) or indirectly through specialized agencies (such as the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission or SASAC at the central and local levels), state investment entities (such as Central Huijin Company, China Securities Finance Corporation, and the National Integrated Circuit Industry Fund), or SOEs that mix commercial and investment activities (such as China National Tobacco Corporation); founders and/or their relatives, management, and corporate pension funds of private-sector companies; private-sector companies like Alibaba and Tencent acting as venture capitalists (The Economist 2018); and foreign investors, e.g., diversified entities like Japan's Softbank or Thailand's Charoen Pokphand, and global asset managers like BlackRock or Canadian pension funds.

For the purposes of our study, the private sector is defined conservatively as those companies, which we label "nonpublic enterprises", in which state entities hold less than 10 percent of equity capital. Within the state sector, a distinction is drawn between those we label SOEs, in which the state owns a majority stake, on the one hand, and those we call "mixed-ownership enterprises," in which the state holds an equity stake between 10 and 50 percent, on the other hand.

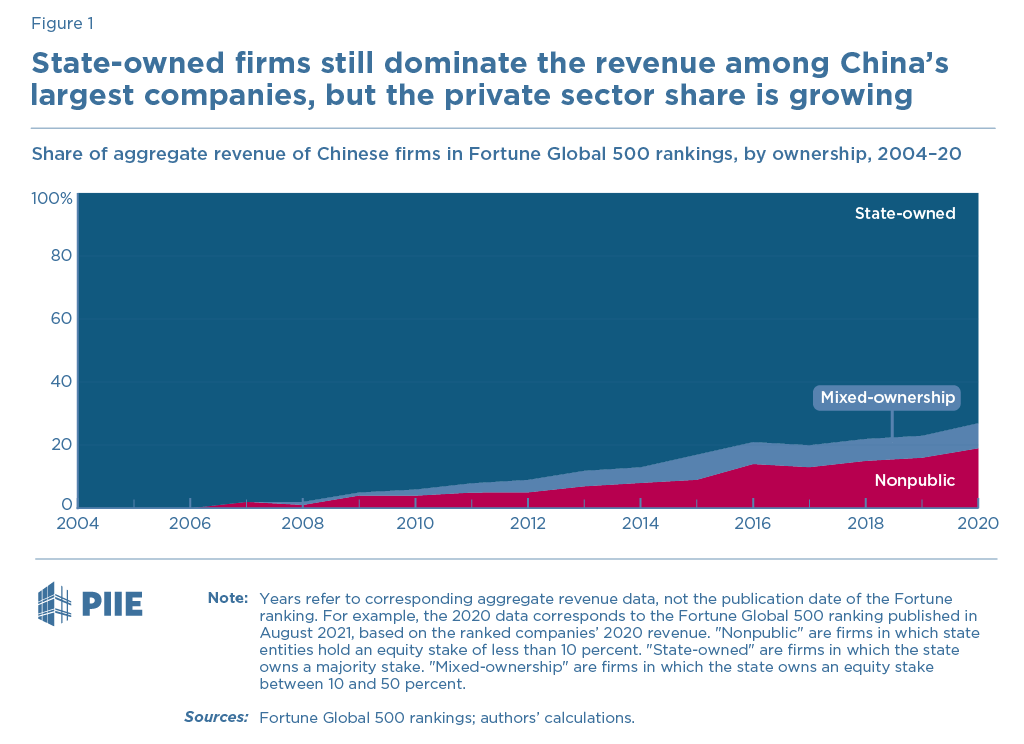

With these definitions in mind, figures 1 and 2 illustrate the rise of the private sector among China's largest companies, measured, respectively, by revenue (all companies) and market value (listed companies). As is clear in figure 1, SOEs still dominate by revenue among the largest companies, much more so than in the Chinese economy as a whole. But the share of the private sector has been steadily rising, from zero in the mid-2000s to 19 percent of the total in Fortune's 2021 ranking, based on 2020 revenue.

Figure 1 Share of aggregate revenue of Chinese firms in Fortune Global 500 rankings, by ownership, 2004-20

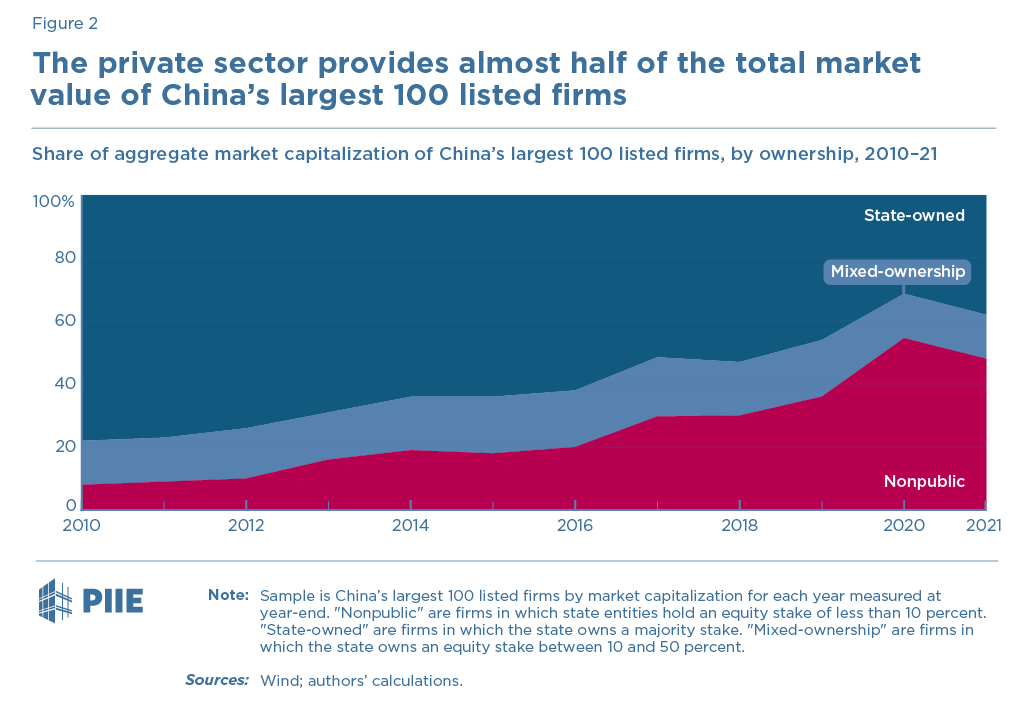

As for market value of the largest listed firms (figure 2), the private sector represented merely 8 percent in 2010 but soared above the 50 percent threshold in 2020, retreating only slightly in 2021 (to 48 percent) despite that year’s major crackdown on certain private-sector-dominated industries, such as internet platforms and after-school tutoring. Thus, the regulatory storm of last summer has stopped well short of reversing the prior advance of the private sector using the market value indicator. In fact, it has not even offset the rise of the private sector’s share in the previous year alone, with the level at end-2021 well above that at end-2019.

Figure 2 Share of aggregate market capitalization of China’s largest 100 listed firms, by ownership, 2010-21

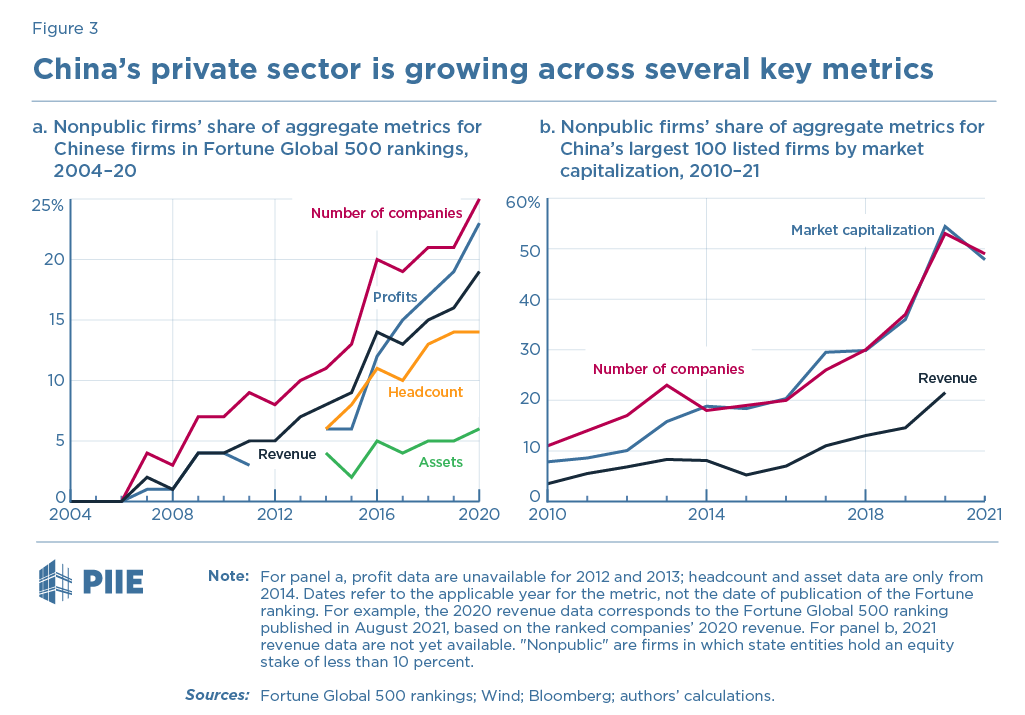

Figure 3 shows similar rising trends for other metrics, based on the same respective samples of companies.

Figure 3 China's private sector is growing across several key metrics

Not privatisation, but displacement of SOEs by better-performing private firms

The advance of the private sector among China's largest companies does not appear to result from long-term planning or top-down decisions, but rather from bottom-up dynamics. Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader who was the main architect of China's embrace of markets starting in 1978, had got it wrong when predicting in 1980 that "whatever the proportion of the private investment will be, this will cover only a small percentage of the Chinese economy. It will by no means affect the socialist public ownership of the means of production." In the 1990s, facing the need to restructure the loss-making state sector, China under Premier Zhu Rongji made a deliberate choice to keep the largest concerns under state control, even as many smaller SOEs were liquidated or privatized. That policy became widely known by the four-character idiom "grasp the large, let go of the small," preserving "public ownership as the mainstay" of China's economic model. In line with these choices, the first large Chinese companies to enter global corporate rankings, whether by revenue or by market value, were all from the state sector until the late 2000s.

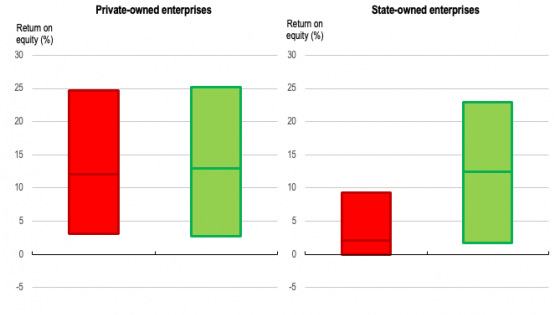

Privatization has been virtually nonexistent among China's largest companies, and has had mixed results when it has happened (Harrison et al 2019). Nor has the state gone out of its way to confer a comparative advantage on the private sector. On the contrary, President Xi declared in 2016 that SOEs must become "stronger, better and bigger." What explains the observed trend, rather than national policies, appears to be that private-sector companies have been more dynamic and profitable than those in the state sector. What China scholar Nicholas R. Lardy has described as the "displacement of SOEs" by private-sector companies has occurred despite a policy environment that clearly does not favor them (Lardy 2019).

The emergence of private-sector champions reflects the spectacular growth of internet content and e-commerce platforms, but is not limited to these. We find a number of other areas where the private sector has become strong, including manufacturing (e.g., electronics, electric cars, batteries, steel, and chemicals), consumer products and services, pharmaceuticals, and life-science companies. The share of platforms in the aggregate market value of China’s large listed private-sector companies in our sample reached a peak about five years ago, and has been declining since then (well before the regulatory storm) as large private-sector companies in other industries grew even faster. By contrast, financial services, telecoms, energy, and transportation remain dominated by SOEs.

Of course, the structural trend of private-sector advance, which has characterized the past decade of development of China's largest companies, is not a failsafe predictor of what will happen next. But claims of a pivot back to state-sector dominance have been made multiple times in the past, and China's private sector has kept advancing in the meantime. There is no compelling indication that this time is different.

References

Abate C, A Elgouacem, T Kozluk, J Stráský and C Vitale (2020), “State ownership will gain importance as a result of COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 7 July.

Büge, M, M Egeland, P Kowalski and M Sztajerowska (2013), “State-owned enterprises in the global economy: Reason for concern?”, VoxEU.org, 2 May.

Harrison, A, MW Meyer, W Wang, L Zhao, M Zhao (2019), “Changing the tiger's stripes: Reform of Chinese state-owned enterprises in the penumbra of the state”, VoxEU.org, 7 April.

Huang, T and N Véron (2022), “The Private Sector Advances in China: The Evolving Ownership Structures of the Largest Companies in the Xi Jinping Era”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 22-3.

Lardy, N (2014), Markets Over Mao: The Rise of Private Business in China, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC.

Lardy, N (2019), The State Strikes Back: The End of Economic Reform in China?, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC.

Lardy, N (2018), “Private sector development”, in R Garnaut, L Song and C Fang (2018), China’s 40 Years of Reform and Development 1978-2018, ANU Press.

The Economist (2018), “Alibaba and Tencent have become China’s most formidable investors”, 2 August.