Africa is not achieving its potential in food trade.

Growing demand for food in Africa is increasingly being met by imports from the global market. This, coupled with rising global food prices, is leading to ever mounting food import bills. Clearly something has to change. Business as usual with regard to food staples in Africa is not sustainable.

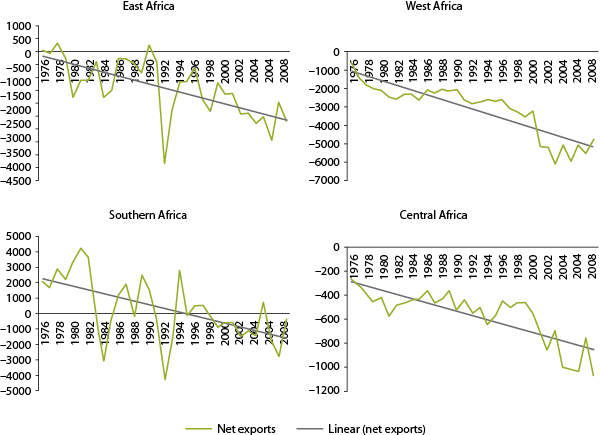

Figure 1. All regions in Africa are increasingly importing food (volume of net exports of food staples: 1,000 tons)

Source: FAOStat

Solutions exist: fertile land, seeds and trade opportunities

Fortunately, there is a solution to this problem within Africa. The potential to increase agricultural production in Africa is enormous. Yields for many crops are a fraction of what farmers elsewhere in the world are achieving, and output could easily increase twofold or threefold if farmers were to use updated seeds and technologies. Also, large swathes of fertile land in Africa remain idle. For example, 400 million hectares of the Guinea Savannah zone (an area the size of India) can be used for agriculture but less than 10% of this is being cultivated (World Bank 2009).

Open regional trade is essential because demand is becoming increasingly concentrated in cities that need to be fed from food production areas throughout the continent. Different seasons, rainfall patterns and variability in production, which will increase as the climate changes, are not conveniently confined within national borders. A model of food security in Africa based around national self-sufficiency is becoming more and more untenable. Cross-border trade in food provides farmers in Africa with the opportunity and incentives to supply the growing demand.

But the potential for Africa’s farmers to satisfy much of the rising demand for food in Africa through regional trade is not being exploited. Currently, only 5% of Africa’s imports of cereals is provided by African farmers. Farmers in Africa face more barriers in accessing the inputs they need and in getting their food to consumers in African cities, than do suppliers from the rest of the world. African smallholder farmers who sell surplus harvest typically receive less than 20% of the consumer price of their products, with the rest being eaten away by various transaction costs and post-harvest losses. This clearly limits the incentive to produce for the market.

Barriers along the value chain

Many of the key barriers to trade in food staples relate to regulatory and competition issues along the value chain. As tariffs have come down it has become increasingly apparent that a tangled web of rules, fees and high cost services are strangling regional trade in food in Africa. In some cases the policies that are restricting trade are deliberately protectionist. In many cases, however, they reflect poorly designed and/or badly implemented policies resulting from lack of broad stakeholder participation and weak capacity in government departments and agencies. Rules and regulations limit access to inputs of seeds and fertilisers and extension services that are critical if productivity potentials are to be achieved. In Ethiopia, the use of improved hybrid maize could contribute to a quadrupling of productivity and replace commercial imports (Alemu 2010). Farmers in Malawi pay three times more for fertilisers than do their counterparts in Thailand.

Logistics

Transport and logistics costs, especially for small farmers, can gobble up as much as half of the delivered price of staples. While there is plenty of need for further improvements in infrastructure ,the key reason for high transport costs is often lack of competition (USAID 2011). Transport cartels are still common in many regions of Africa, and the incentives to invest in modern trucks and logistics services are very weak.

Opaque trade policy

Opaque and unpredictable trade policies continue to raise trade costs. Trade in staples in Africa continues to be affected by measures such as export and import bans, variable import tariffs and quotas, restrictive rules of origin, and price controls. Often these are decided upon without transparency and are poorly communicated to traders. This creates uncertainty about market conditions and limits cross-border trade. Inefficient distribution services also hamper regional trade in food. Poor people in the slums of Nairobi pay more pro rata for food staples than the wealthy pay at supermarkets. This reflects that in many countries the distribution sector is not effectively linking poor farmers and poor consumers. Price controls imposed across the region and the cartels in place in several African countries represent a serious impediment to competition.

All these barriers raise costs and increase uncertainty, make regional markets smaller, and increase volatility. Indeed, the price of maize in Africa has been more volatile than the world price of maize. Policies that reduce transaction costs and increase competition in the provision of services, that affect the production and distribution of food staples, would reduce the gap between consumer and producer prices.

Current policies constrain institutions

The development of institutions that would support African farmers in reducing risks and raising productivity is compromised when the trade policy environment for staples is difficult and uncertain. Effective standards regimes depend upon private sector involvement, but in many countries the process of defining standards is often dominated by government agencies. Private investments in storage capacity, which would help reduce the enormous post-harvest losses and allow farmers to sell when prices are most favourable, are undermined when policies that influence prices, such as export bans, are uncertain and lack transparency. Commodity exchanges, which have the potential to reduce transaction costs for farmers by reducing the number of intermediaries and improving the conditions of exchange, cannot thrive without even-handed and predictable policies. Operating across borders would allow exchanges to build sufficient trading volume to exploit scale economies and be more profitable.

Institutions that can help address food security concerns and so reduce the political risk from reform will only flourish if there is a change in the way that food trade policies are defined and implemented. For example, futures and options markets provide an alternative to holding physical stocks through food security reserves, and weather-indexed insurance can mitigate the impacts of climatic shocks on farmers.

Political economy issues limit implementation of open regional trade

Despite commitments towards opening up regional trade in food, implementation has been very weak. Few governments have sought to build a constituency for reform. Opening up food staples to regional trade will lead to both winners and some losers. Where reform reduces the mark-up between producer and consumer prices, it is farmers and poor consumers who will gain while intermediaries earning rents, both in public sector agencies and in the private sector, will lose. Reform becomes particularly difficult when politicians themselves are involved in the production and distribution of food. The absence of a stable and predictable policy environment breaks down trust and constrains private-sector investment in food staples, which in turn limits production and trade. And it encourages governments to continue to hedge against the failure of the private sector to adequately supply food when shortages do arise.

Two key features can assist governments in creating constituencies for reform:

- An inclusive dialogue on food trade reform informed by timely and accurate data on global, regional, and national markets.

In many African countries decisions about food trade policies are made mainly at the highest levels of government, too often without critical analysis and consideration of options. Food trade policy is rarely subject to open discussion, and the interests and views of the broad group of stakeholders in food staples trade policies are seldom represented.

- A reform strategy that provides a clear transitional path to integrated regional markets, rather than a single but politically unfeasible jump to competitive markets.

The nature and range of the barriers to trade along the value chain, and the need to invest in market-supporting institutions, show that delivering integrated regional food markets involves more than a one-off commitment, and that reforms cannot be implemented at the stroke of a pen. Thus, for many policymakers the goal of open and competitive regional markets will not occur during their electoral terms. The reform strategy thus needs to define incremental steps that encourage investment by offering certainty to the private sector about policies. It should deliver real and visible benefits, while allowing policymakers to move at a pace consistent with their capacities and political risks.

Conclusions

With as many as 19 million people living with the threat of hunger and malnutrition in west Africa’s Sahel region, and the demand for food throughout Africa predicted to double over the next decade, governments can act now to overcome these political economy realities and remove barriers along the value chain.

A regional approach to food security in Africa will allow governments to more effectively and efficiently meet their objectives of ensuring access to food for their populations. This brings the prospect of not only benefits to farmers and consumers but also of a significant number of new jobs in activities along the value chain of staples – in producing and distributing seeds and fertilisers, in advisory services, consolidating and storing grains, transport and logistics, distribution, retailing, and processing.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the institution with which he is affiliated. This column summarises a longer report which is available, together with an accompanying film and interviews, at http://go.worldbank.org/PQ65YEGB60

References

Alemu , Dawit (2010), "The Political Economy of Ethiopian Cereal Seed Systems: State Control, Market Liberalisation and Decentralisation", Future Agricultures Working Paper, 17.

USAID (2011), "Regional Agricultural Transport and Trade Policy Study", West Africa Trade Hub Technical Report, 41, United States Agency for International Development.

World Bank (2009), Awakening Africa’s Sleeping Giant: Prospects for Commercial Agriculture in the Guinea Savannah Zone and Beyond, Washington, World Bank.