Views on Africa’s growth prospects have jumped from utter pessimism to extreme enthusiasm. The latter has been centre-stage with the US–Africa Summit hosted in Washington DC from 4–6 August 2014, with the participation of top political and business leaders. My coauthors Todd Johnson and Shlomi Kramer and I have tried to take a sober assessment of Africa’s progress and prospects, looking beyond the current hype and the inevitable frustration that doing business in the region still generates (Annunziata et al. 2014).

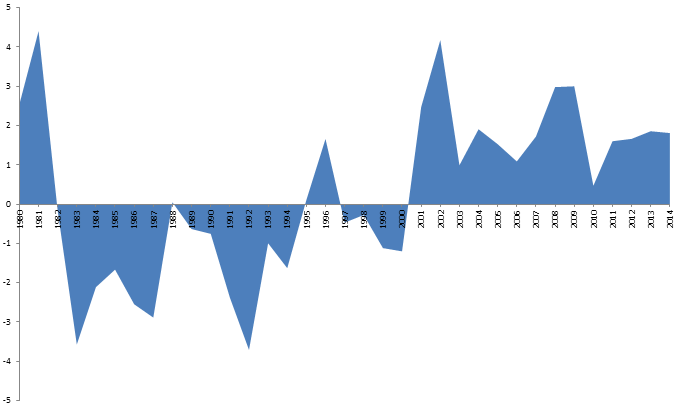

There is no doubt that Sub-Saharan Africa has earned attention through an impressive growth spurt. After two decades of underperformance, starting in 2001 Sub-Saharan Africa has exceeded global growth by two percentage points per year; since the Global Crisis it has emerged as the second fastest-growing region, with an average annual growth of 5%, closing in on emerging Asia. It is now seen as the new most promising growth market.

Figure 1. Sub-Saharan African growth vs. global growth

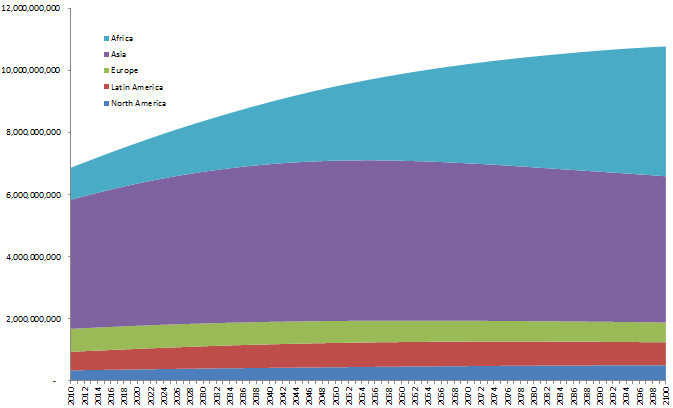

Add to this a sizeable, young, and growing population. According to UN projections, Africa’s population will rise rapidly from today’s 1.1 billion, adding another 200 million people by 2020; it will double by 2050 and quadruple by 2100. At that point, it will be on a par with Asia’s, each at 40% of the world total. If these demographic projections hold, and economic growth remains robust, Africa will become home to a very large middle class. You can see why global corporations as well as financial investors are looking with such interest at a region that today still accounts for only 2% of the global economy.

Figure 2. Long-term population growth projections

But will this growth performance be sustained? Commodities have played a big role – Sub-Saharan Africa’s fortunes began turning when the commodity cycle picked up steam in the late 1990s.

Figure 3. Commodity prices and Sub-Saharan African growth

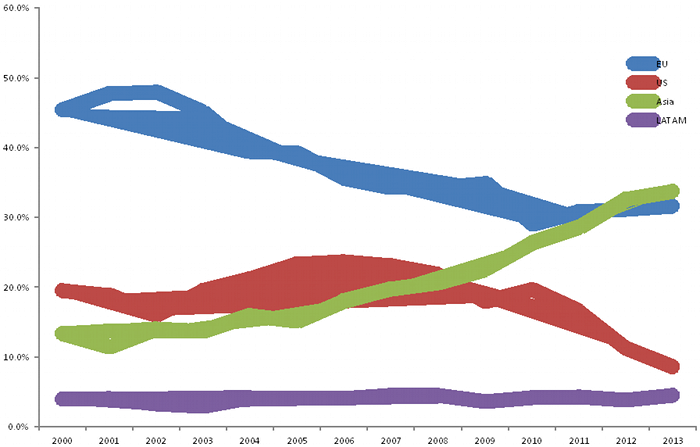

Investment in commodities was accelerated by the rapid development of other emerging markets, and in particular by the rise of China. Sub-Saharan Africa’s trade with Asia has grown much faster than with any other region, overtaking trade with Europe and reaching over a third of the region’s total trade in 2013 (China accounts for roughly half).

Figure 4. Sub-Saharan Africa’s shares of international trade by destination region (% of total)

There is more to the story than commodities, however. A number of African countries have put in place meaningful improvements in governance and institutions as well as economic policymaking. The approach has been gradual, in line with the ‘just enough governance’, second best approach recommended by Fukuyama and Levy (2010) and Rodrik (2004, 2008) – instead of trying to improve all aspects of policymaking at once, focus on addressing the biggest distortions and the most binding capacity and institutional constraints. The business environment has improved, with most African countries getting closer to the best practice frontier in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings. Botswana, Ghana, Rwanda, South Africa, and Zambia now rank ahead of all the BRICs.

There is open debate on whether the ‘just enough’ approach is preferable to a ‘big bang’ effort. In Africa, this gradual and pragmatic strategy has helped score some quick wins on the economic front, but a lot remains to be done. Doing business in Africa is still very challenging, and the overall state of infrastructure remains poor across the continent – Sub-Saharan Africa lags behind other developing regions in almost all measures of infrastructure coverage, with particularly large gaps for electricity supply, access to water, and road transport. This has so far impeded the development of a stronger and more broad-based manufacturing sector – even in countries not facing the Dutch-disease challenge of commodities (with South Africa being the only exception).

Macroeconomic vulnerability indicators reveal a mixed picture. Government debt levels are fairly low, with all major countries below the benchmark 60% threshold. Improved policymaking has helped reduce inflation rates across the region. A number of countries, however, run large current-account deficits. Even with a high coverage in foreign direct investment, these are a source of concern, particularly as the gradual correction in US monetary policy is likely to trigger renewed volatility in international capital flows. Ghana has recently turned to the IMF for help, following a very sharp exchange-rate depreciation; Zambia and South Africa also stand out as vulnerable.

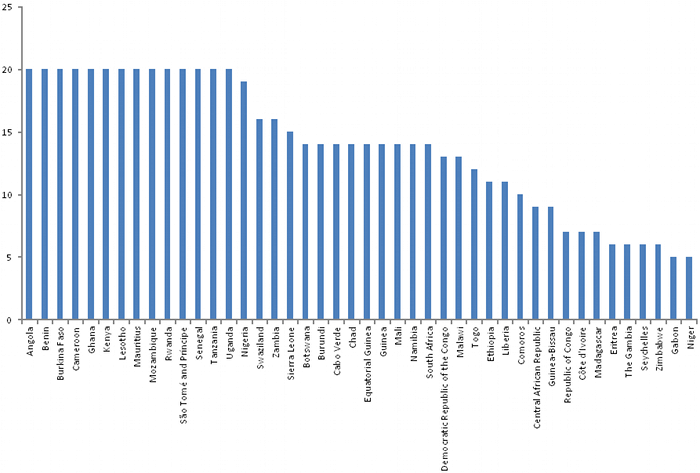

Overall, though, Africa has made huge progress, and it shows. Since 1995, about two-thirds of the countries in the region have recorded positive economic growth for at least 10 consecutive years, and about one-quarter have enjoyed 20 years of uninterrupted economic expansion. In the process, they have weathered the Global Crisis and the slowdown in the commodity cycle of the last two years. This is tangible evidence that there is more to the story than a commodity boom. In the process, the region has attracted strategic investments from China, India, and a number of multinational corporations.

Figure 5. Years of uninterrupted positive growth since 1995

The risk of backsliding, however, is still present. Economic growth has not yet translated into a sufficiently broad-based increase in living standards, leaving many of the region’s citizens dissatisfied with their governments and frustrated with still-high levels of inefficiency and corruption. Unless this changes, the risk of social and political instability cannot be ignored. A lot more progress is needed in strengthening political and social institutions and in pushing market-oriented economic reforms. This would help to broaden the base of growth beyond commodities and to develop a stronger manufacturing sector, which in turn would provide jobs and incomes on the scale needed to bolster the size of the middle class. In short, more progress is needed before reforms become self-sustaining.

Further efforts will need to focus in four key areas:

(1) Infrastructure.

Dense and efficient transportation networks would facilitate trade and communications, allowing economic development to spread into rural areas. More reliable and distributed power would facilitate manufacturing activities. Better access to power, together with portable cost-effective healthcare, would ensure better living conditions and health standards – making it easier for citizens to be more engaged in the political process and supporting a further improvement in governance.

(2) Trade integration, within the region and globally.

The creation of a common African market underpinned by a joint infrastructure strategy would make it easier for African companies to achieve scale and gain competitiveness on the global scene, boosting growth, employment, and productivity.

(3) Human capital.

If strong growth continues and spreads to a wider range of sectors, the limited availability of a qualified local workforce will become a serious constraint. Company-sponsored training programs could play an important role in filling the gap, creating the skills needed by fast-developing industries. Governments and companies should cooperate in the development of professional schools closely aligned to industry, to match the supply of skills with demand.

(4) Innovation

In our latest GE Global Innovation Barometer (GE 2014), about 80% of business executives in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa see innovation as a positive force that has already helped raise living standards in their countries. The viral success of M-Pesa, the mobile-banking and micro-financing system that quickly bypassed the relative under-development of traditional banking, shows that Africa is ready to be an early adopter of new technologies that can help by-pass structural weaknesses.

Africa is at a crossroads. The opportunities are huge, but the road ahead is long, and will require persistent and patient effort from policymakers as well as business. We are optimistic.

References

Annunziata, Marco, Todd Johnson, and Shlomi Kramer (2014), “Growth and Governance in Africa: Towards a Sustainable Success Story”, GE Ideas Lab.

Francis Fukuyama and Brian Levy (2010), “Development Strategies: Integrating Governance and Growth”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

GE (2014), “GE Global Innovation Barometer 2014 – Insight on Disruption, Collaboration and the Future of Work”.

Rodrik, Dani (2004), “Getting Institutions Right”, Harvard University Weatherford Center for International Affairs.

Rodrik, Dani (2008), “Second best institutions”, Harvard University Kennedy School of Government.