There are substantial social costs from the excess consumption of alcohol, including the healthcare costs of treating diseases such as liver cirrhosis, as well as the costs of anti-social behaviour and drink driving. In a simple textbook setting, a Pigouvian tax levied on the source of an externality – ethanol, in this case – is the best policy. However, the assumptions underpinning this result often break down in practice – for example, when the marginal externality of some forms of consumption is higher than others. There is evidence to suggest that this is true for alcohol, with the consumption of heavier drinkers being considerably more costly than that of lighter drinkers. When this is the case, a single tax rate must trade off price rises that are too low for the most socially costly consumers and too high for others (Diamond 1973).

Recently, price floors have been advocated as an effective policy to tackle problem drinking. Price floors are common in labour markets to redistribute to workers and agricultural markets to protect small upstream producers from monopsony power; however, they are banned in most other settings to protect consumers. Price floors can lower socially costly consumption by raising prices, but, unlike higher taxes, they can create windfall profits for firms instead of raising tax revenue, so have not been favoured by economists.

What effect did the introduction of a price floor in Scotland have on prices and quantity purchased?

In a recent paper (Griffith et al. 2020a), we study the impact of a price floor for alcohol on prices and quantities, and compare its welfare effects with those of a tax levied on ethanol. We exploit the introduction of a price floor for alcohol in Scotland but not in other parts of the UK. The policy came into effect in May 2018 and made it illegal to sell alcoholic drinks for less than £0.50 per unit of alcohol. A unit of alcohol is 10ml of ethanol and is the standard metric in the UK. The UK government advises people not to drink more than 14 units per week.

We use longitudinal micro data on the alcohol purchases from supermarkets and off-licenses (liquor stores) of over 30,000 Scottish and English households before and after the reform.

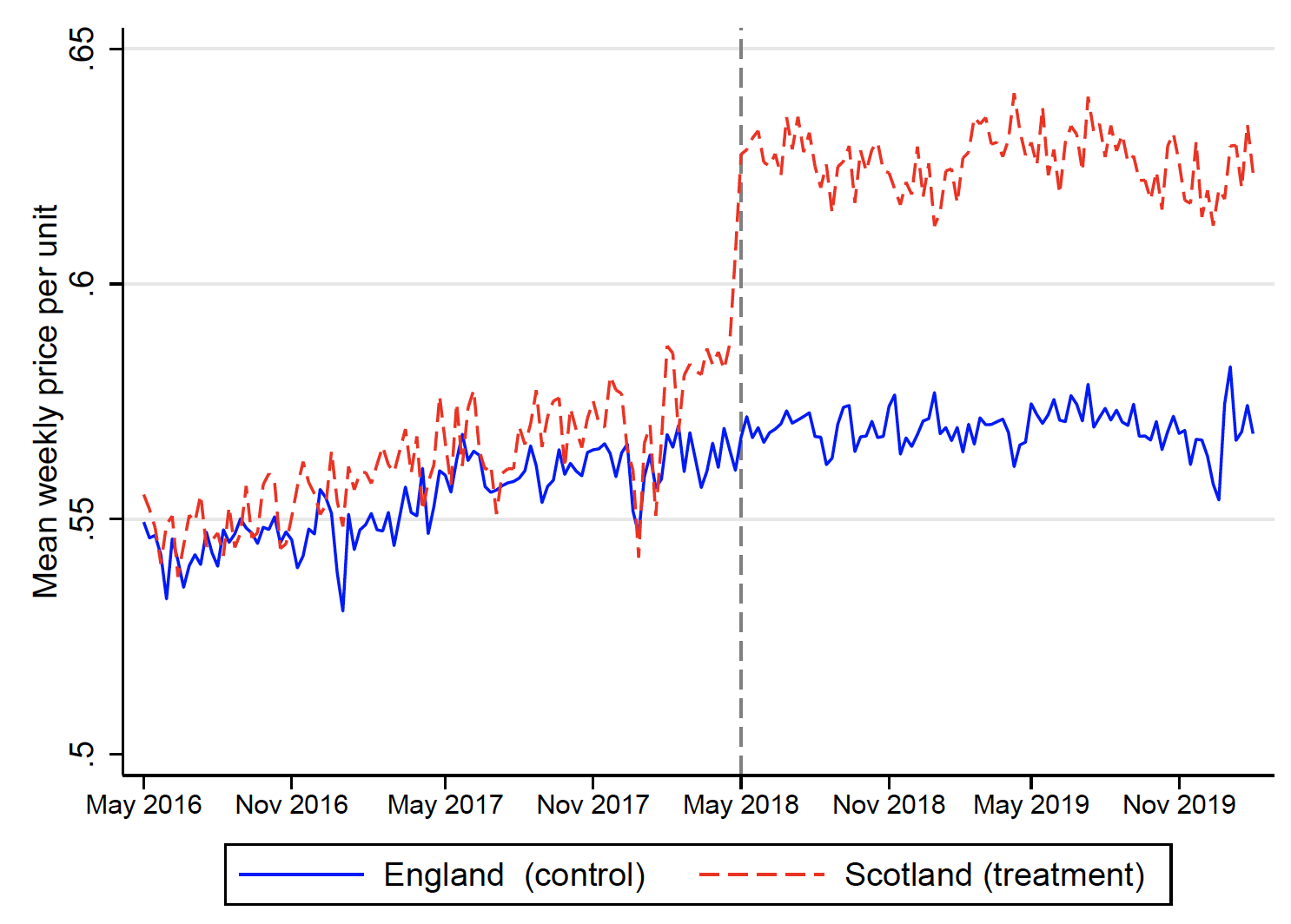

Figure 1 shows that average prices and purchases moved similarly in Scotland and England prior to the reform, and that average prices rose sharply and the quantity of alcohol purchased declined in Scotland following the introduction of the price floor. We use a difference-in-differences estimator, controlling for time, product and household fixed effects, to show that the policy led to a 5% rise in average price per unit of alcohol across products, and an average reduction of 11% in quantity purchased.

Figure 1 Average alcohol prices and purchases in England and Scotland, 2016-20

(a) Price per unit

(b) Units per adult per week

Notes: The top panel shows the mean price paid per unit of alcohol, and the bottom panel the mean units purchased per adult per week across households relative to the first week in May 2016, in England and Scotland in each week from May 2016 to January 2020. We remove country-specific week effects from all series. The dashed vertical line shows the introduction of the Scottish price floor on 1 May 2018. 1 unit of alcohol = 10ml of ethanol.

Source: Griffith et al. (2020a).

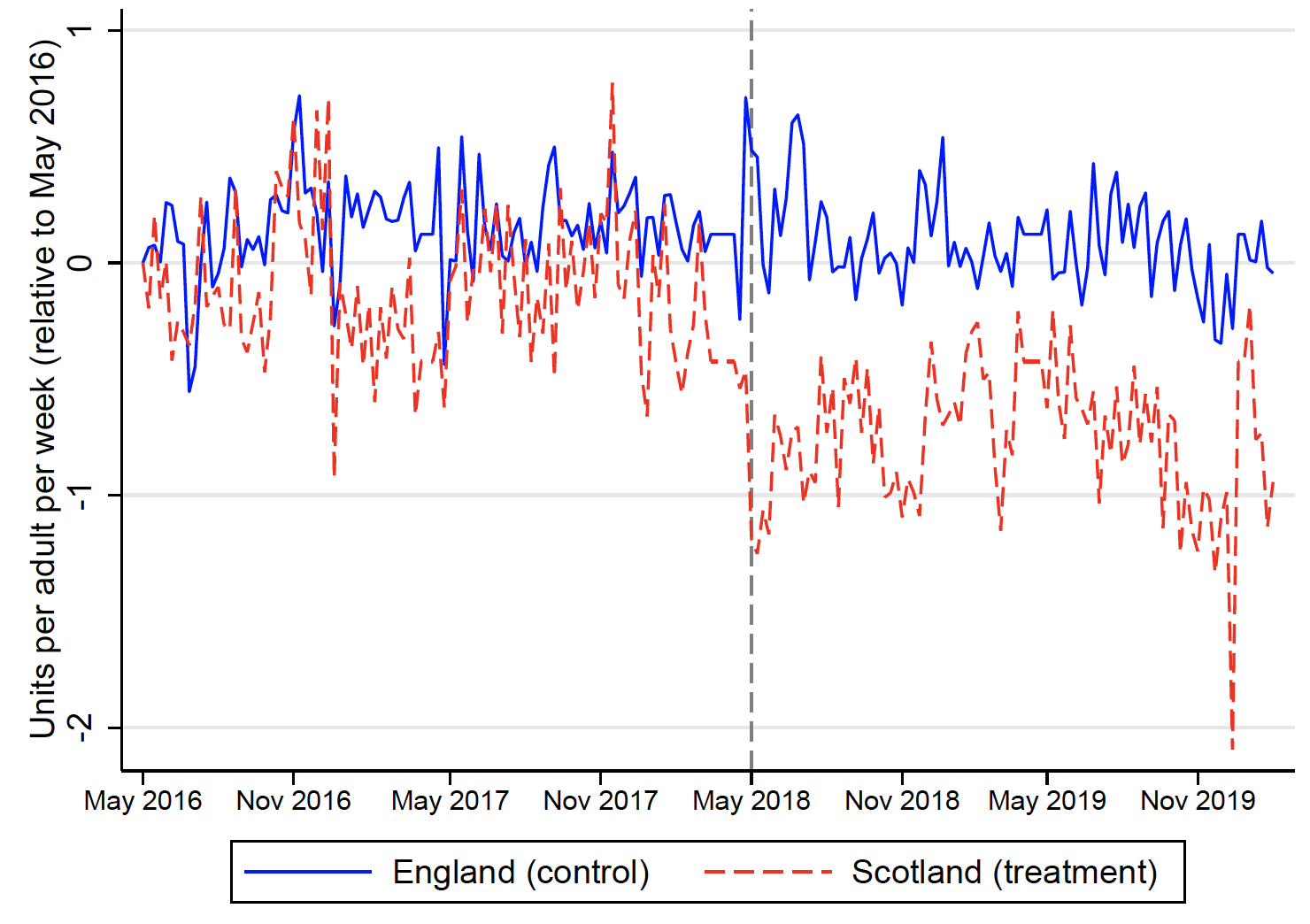

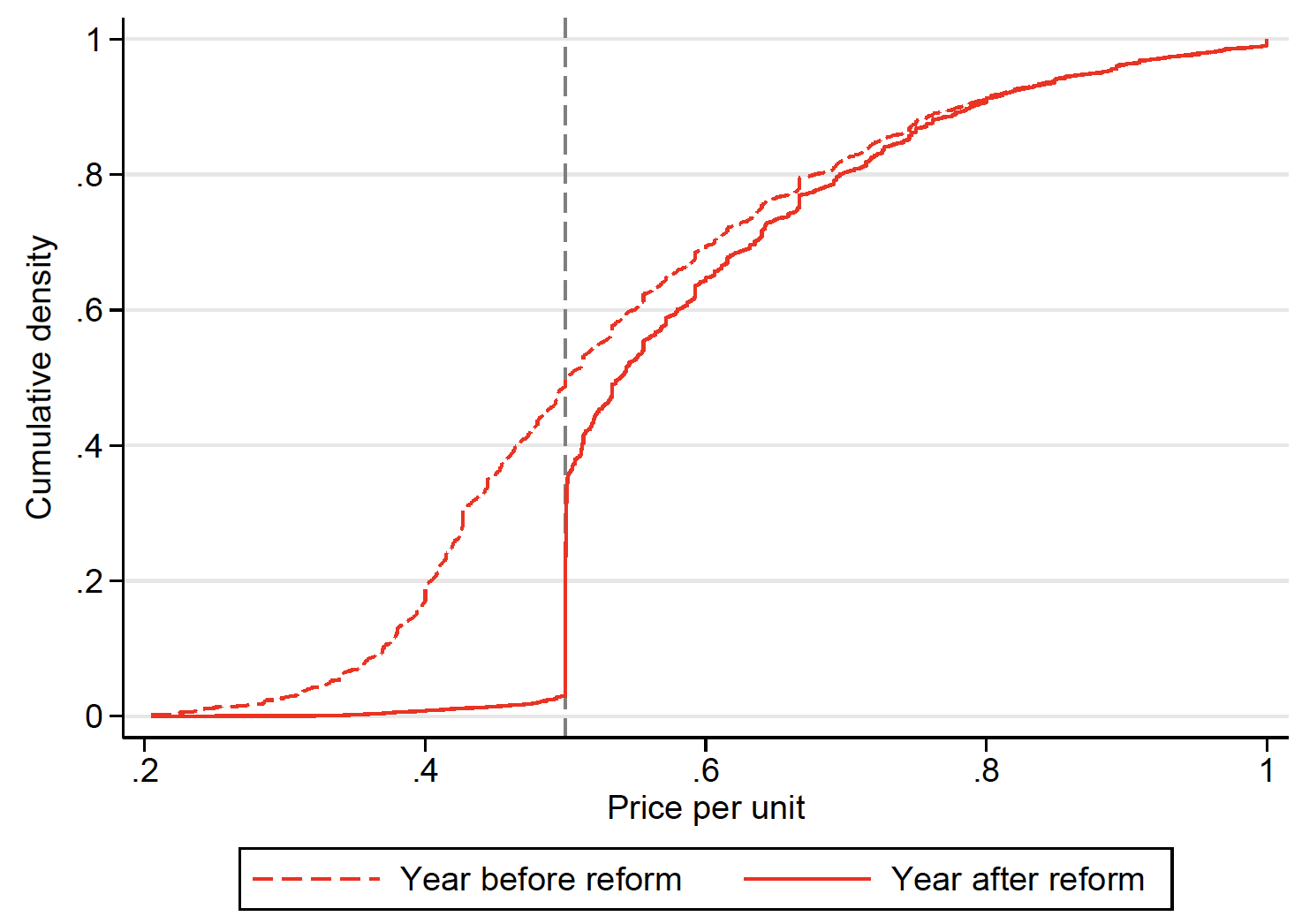

This average price increase masks a great deal of variation in the price changes experienced by different products. Figure 2a shows that prior to the reform close to 50% of transactions in Scotland in the year before the reform were below the floor. Figure 2b shows the distribution of prices before and after the introduction of the reform, and the average price change conditional on the product’s price in the year prior to the reform. Some very cheap products experienced price increases in excess of 100%, while products that were previously priced above the floor exhibit very little change in price.

Figure 2 Effect of the price floor across the price distribution in Scotland

(a) Price distribution

(b) Mean price changes

Notes: The top panel shows the distribution of price paid per unit across transactions in the year before and the year after the introduction of the price floor in Scotland. The bottom panel shows, for the set of products that are recorded as purchased in the year before and after (which account for 80% of spending across the two years), the average change in price per unit, conditional on the product's average price in the year preceding the reform.

Source: Griffith et al. (2020a).

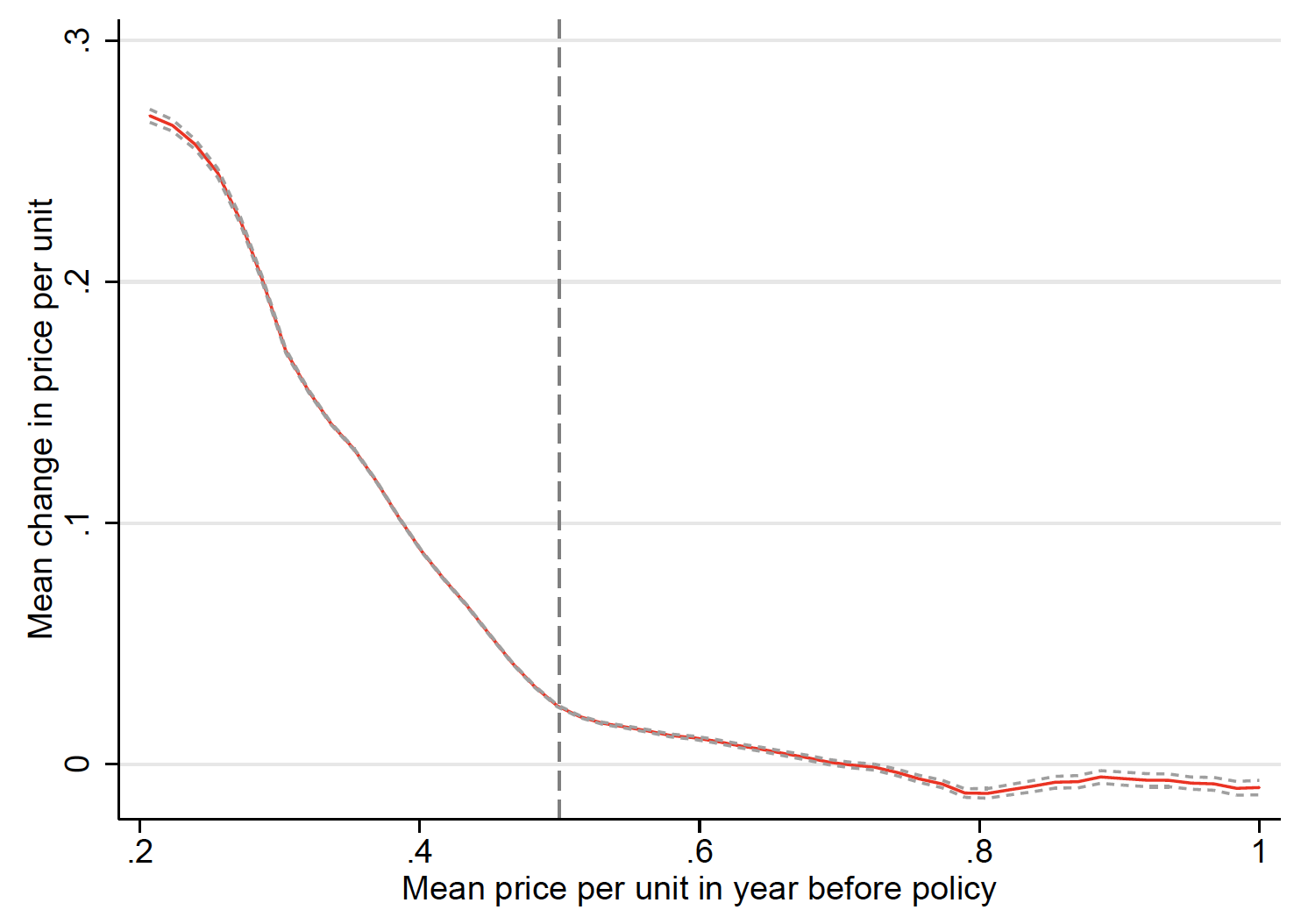

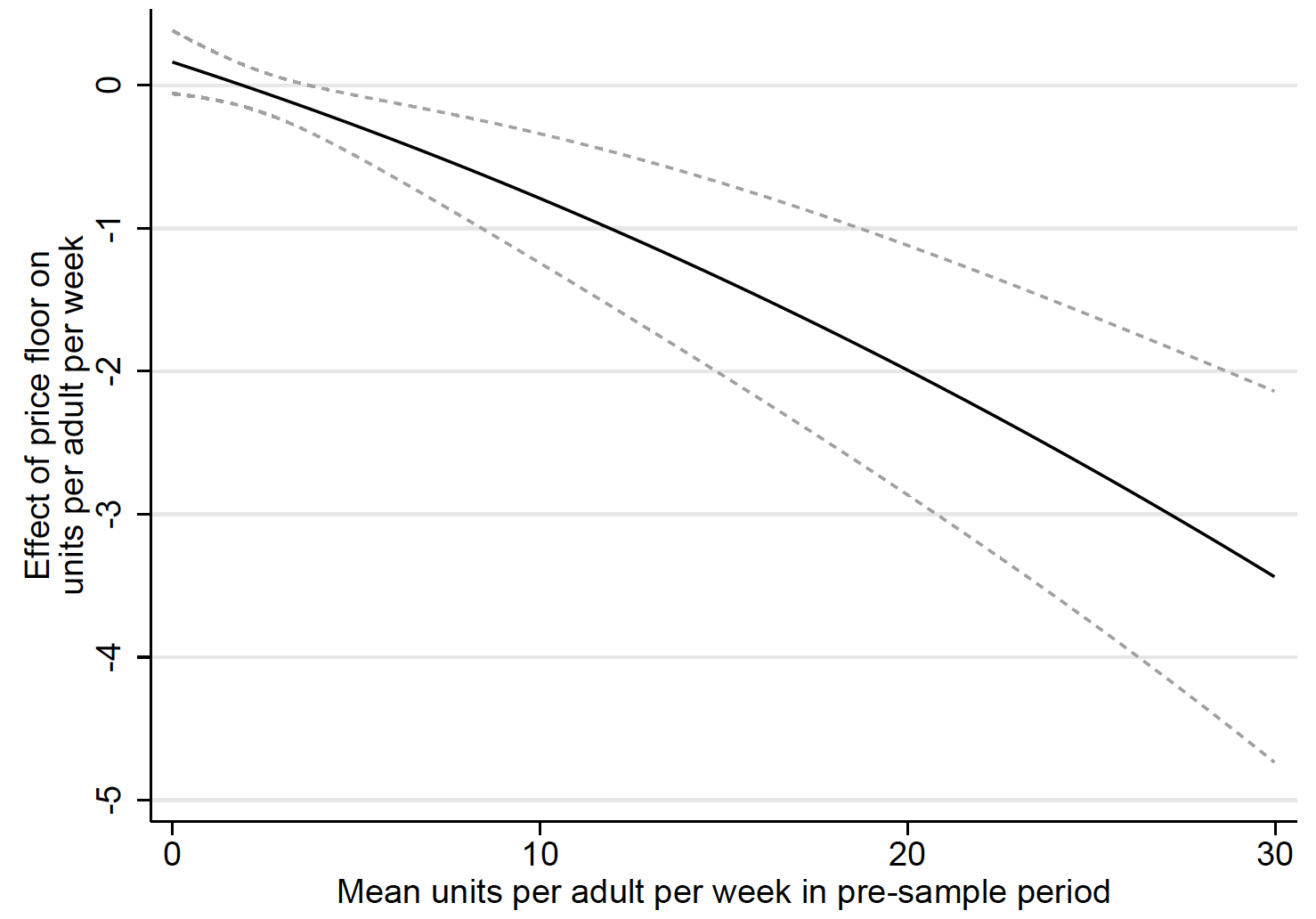

The policy led to much larger increases in the price of cheap (per unit of alcohol) products. This makes it relatively well targeted at the alcohol purchases of heavy drinkers, because they disproportionally buy relatively cheap alcohol products. Households that bought, on average, less than five units per adult per week got around 40% of their alcohol from products priced below the floor in 2017. This rises to well over 60% for households that bought more than 20 units per adult per week on average. Figure 3 shows the impact of the price floor on the alcohol purchases of households across the drinking distribution. We estimate that the policy led to an average decline in units purchased of 0.63 (11%), with larger falls for more heavily drinking households.

Figure 3 Effect of the price floor across the distribution of drinkers

Notes: The solid line plots the estimated treatment effect of the price floor as a function of the household’s mean units purchased per adult per week over May 2016 to April 2017.

Source: Griffith et al. (2020a).

How does a price floor compare to an ethanol tax?

In order to compare the welfare impact of price floor to that of a simple Pigouvian-style tax on ethanol, we estimate a model of demand for alcohol products using data from a period well before the introduction of the price floor in Scotland. We build on the discrete choice demand model in Griffith et al. (2019), which models the consumer’s decision over whether to buy alcohol, what type to buy, and how much. We allow for variation in preferences across light, moderate and heavy drinkers, and by household income. This allows us to assess how the policies affect those whose consumption is likely to create differing levels of externalities, in addition to evaluating the distributional implications of the reform.

We estimate that the heaviest drinking households have higher own-price elasticities for individual alcohol varieties, but they are also the most willing to switch between varieties when the price of one changes (and less likely to switch away from alcohol altogether). As a result, their total demand for alcohol is substantially less elastic than the lightest drinkers.

Our demand model embeds a number of identification and functional form assumptions. We therefore assess the validity of the model by comparing its out-of-sample predictions of the impact of the price floor with those estimated using the difference-in-differences approach. We find that the model does a good job of predicting the average effect on quantity purchased, as well as variation across light and heavy drinkers and by different alcohol types.

We use the model to compare the welfare impact of the price floor with that of an ethanol tax that achieves the same aggregate reduction in alcohol as the price floor. When the externality associated with each unit of alcohol consumed is constant, the ethanol tax out-performs the price floor, increasing welfare by more than the price floor. However, when the alcohol consumption of heavy drinkers creates even moderately larger externalities than that of lighter drinkers, the price floor leads to larger welfare gains than the ethanol tax. This is because the price floor is much better targeted at heavy drinkers, and thus leads to a larger reduction in external costs, which more than offsets the fact it leads to losses in tax revenue.

However, reforms to the tax system that tax stronger drinks more heavily can achieve similar welfare gains to the price floor. This is because they increase the price of stronger alcohol products by more, which are also consumed disproportionately by heavy drinkers. In Griffith et al. (2020b), we show that a simple two-rate tax system that taxes drinks in proportion to their ethanol content, with a higher rate on strong spirits, is almost as well targeted at heavy drinkers as a price floor, but leads to an increase in tax revenue. Until now, EU regulations have constrained the UK's ability to reform alcohol taxes in this way, but this type of reform may now be possible.

Negative consumption externalities are common and often do not fit the textbook setting that would make a Pigouvian-style tax the most appropriate policy. Our findings suggest that a price floor can be a useful policy instrument, particularly when those whose consumption is the mostly socially costly tend to buy particularly cheap variants and are price sensitive. A similar idea of ‘targeting’ socially costly consumption by raising taxes on products preferred by high externality consumers underpins the results in Griffith et al. (2019). A benefit to using a price floor is that it sidesteps the problems associated with ‘line drawing’ (Gilitzer et al. 2015) that may hamper the implementation of increasingly complex systems of excise taxes. Nonetheless, it is important to consider how the price floors interact with the system of alcohol duties – the extent of revenue losses under a price floor can be mitigated by a sensibly designed tax system.

References

Diamond, P A (1973), “Consumption externalities and corrective imperfect pricing”, The Bell Journal of Economics 4(2): 526–538.

Gillitzer, C, H J Kleven, and J Slemrod (2015), “A Characteristics Approach to Optimal Taxation: Line Drawing and Tax-Driven Product Innovation”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics.

Griffith, R, M O’Connell, and K Smith (2019), “Tax design in the alcohol market”, Journal of Public Economics 172: 20–35 (see also the Vox column here).

Griffith, R, M O’Connell, and K Smith (2020a), “Price floors and externality correction”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15476.

Griffith, R, M O’Connell, and K Smith (2020b), “Tackling heavy drinking through tax reform and minimum unit pricing”, IFS Briefing Note BN 311.