Cartels are a clear and ever-present violation of market economics (see Verboven and van Dijk 2007). Catching cartels is a key function of governments around the world. But to catch them, it helps to understand them. To understand how cartels work, it is of first-order importance to analyse which issues cartels aim to solve and how. Our understanding of cartel organisation and operation remains inadequate even though it has improved during the recent years through both in-depth analyses of individual cartels, game-theoretic modeling of cartel contracts and qualitative analyses of cartel contracts.

Cartel contracts

A key factor inhibiting further progress has been lack of data that would allow a quantitative analysis of the nature of horizontal agreements that the firms seeking collusive arrangements enter: that is, how do the cartel contracts look like? Are they very similar, or not? Which contracting features are used most often? Do some features of contracts appear together often?

In Hyytinen, Steen and Toivanen (2013), we use detailed data on 18 different contract clauses of 109 legal Finnish manufacturing cartels, all operating in a shared institutional environment to provide an anatomy of cartel contracts, i.e., a list of their stylised facts. While legal, these cartels seem to have not used the legal system to enforce their contracts, quite similarly to the US Sugar Institute analysed by Genesove and Mullin (2001).

Understanding the anatomy of cartel contracts is important in two ways:

- First, it provides information on how cartels operate.

Such knowledge helps, for example, competition authorities to decide where to allocate resources for the detection of cartels and courts and legal scholars to determine the nature of cartel agreements and concerted actions (e.g. Kaplow 2011a,b). It also may help policymakers to understand the consequences and limits of competition and regulation (Shleifer 2004, 2012).

- Second, it adds to the existing literature on cartels (e.g., Levenstein and Suslow 2006, 2011; Harrington 2006) to provide a basis for further development of cartel theory towards models that are in line with stylised facts.

Such models are instrumental in pushing our understanding further on how cartels operate, and what types of policies are likely to be effective against them.

Cartels have to solve two fundamental issues: how to raise profits, and how to deal with the inherent instability of the cartel agreement. One third of the 18 different contract clauses that we study relate to raising profits; the rest deal with instability through incentive compatibility, cartel organisation, or external threats.

Main findings

First, we find – consistent with the prior literature – that cartels coordinate on pricing, allocate the market and/or coordinate on the positioning in the product space (i.e., who specialises on what). We also find that many, but not all, cartels contract on the incentive compatibility constraint, some aspect of their internal organisation as well as on how to deal with external threats.

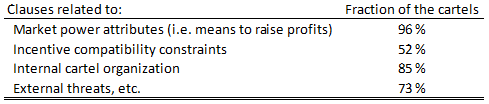

Table 1 provides basic descriptive statistics for our sample. It shows, for example, that out of the cartel contracts in our sample, 52% has at least one clause that deals with or is related to the incentive compatibility constraints.

Table 1. Prevalence of various contract clauses

Source: Hyytinen, Steen and Toivanen (2013).

Scrutinising the contracting patterns closer we find that cartels appear to use three main approaches: to raise profits, they either fix prices, allocate markets or specialise in some way. These appear to be substitutes. Moreover, choosing one of these approaches has implications on how cartels deal with instability.

We also look closer on how the cartel contracts relate to the size of the cartel in terms of the number of members and to whether the industry produces homogenous or differentiated products. We find that:

- The size of the cartel is associated with how the cartel seeks to raise profits: the number of cartel members is positively correlated with agreeing on prices, and negatively correlated with using the non-competition/specialisation clause. Cartel size is also positively associated with the use of instability clauses.

- Cartels in homogenous goods industries are more likely to use market allocation to raise profits.

Clauses relating to the incentive compatibility constraint and external threats are also more likely to be used by cartels in these industries.

- Furthermore, the relationship between how a cartel raises profits and how it deals with instability are to some extent explained by the number of members and homogeneity of products.

The contract data allow us to provide an exploratory analysis of the complexity and stability of cartel contracts. The prior literature is largely silent about them, but they are potentially important in informing policy (e.g., can relatively simple and short contracts sustain collusion?) as well as in furthering the economic theory of cartel contracts (e.g., how often are contracts updated?). We find some evidence that larger cartels use more complex contracts (measured by the number of pages and the number of clauses), as do cartels in industries with product differentiation. While both pricing and market-allocation cartels seem to have more complex contracts, pricing cartels also change them more often.

The cartels in our sample were legal, but apparently they hardly ever used the legal system to enforce their cartel contracts. Thus, there were few reasons at the initial contracting stage to consider the degree of verifiability of the various clauses in the court of law. Had there been such reasons, it could have led to endogenous contract (in)completeness (Kvaløy and Olsen 2009).

It seems clear that the need of illegal cartels to conceal their agreements and behavior will lead to further endogenous incompleteness of contracts. From this point of view one could think that the contracts we’ve studied are the type of contracts illegal cartels would like to write, had that no legal consequences. This means that observed differences between contracts of legal and illegal cartels are likely to be due to the competition law regime that the latter face: The profit, incentive and organisational issues illegal cartel meet, as well as those relating to changes in the external environment, are similar to those faced by the legal cartels that we have studied.

Conclusions

Our findings provide information on the types of concerted action and horizontal agreements that competition authorities and courts should expect and to search for. This complements the prior research that has shown which markets and industries are more prone to collusion and cartels (e.g. Symeonidis 2003). Taken together, this cumulating knowledge should ultimately increase the likelihood of cartel detection and also the probability that courts are able to make a proper ruling in cases involving prohibited horizontal agreements (Kaplow 2011a,b).

References

Genesove, David and Mullin, Wallace (2001), “Rules, Communication, and Collusion: Narrative Evidence from the Sugar Institute Case”, The American Economic Review 91(3), 379-398.

Harrington, Joseph E, Jr (2006), “How Do Cartels Operate? Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics” 2(1), 1-105.

Hyytinen, Ari, Steen, Frode, and Toivanen, Otto (2013), “Anatomy of Cartel Contracts”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9362.

Kvaløy, Ola and Olsen, Trond E (2009), “Endogenous Verifiability and Relational Contracting”, The American Economic Review 99(5), 2193-2208.

Kaplow, Louis (2011a), “On the Meaning of Horizontal Agreements in Competition Law”, California Law Review 99(3), 683-818.

Kaplow, Louis (2011b), “Direct versus Communications-Based Prohibitions on Price Fixing”, Journal of Legal Analysis, 3(2), 449-538.

Levenstein, Margaret C and Suslow, Valerie Y (2006), “What Determines Cartel Success?”, Journal of Economic Literature XLIV, March, 43-95.

Levenstein, Margaret C and Suslow, Valerie Y (2011), “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do: Determinants of Cartel Duration", Journal of Law and Economics 54(2), 455-492.

Shleifer, Andrei (2005), “Does Competition Destroy Ethical Behavior?”, The American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 94(2), 414-418.

Shleifer, Andrei (2012), The Failure of Judges and the Rise of Regulators, MIT Press.

Symeonidis, George (2003), “In Which Industries is Collusion More Likely? Evidence from the UK”, Journal of Industrial Economics LI, No. 1, 45-74.

Verboven, Frank and Theon van Dijk (2007), "Designing the rules for private enforcement of EC competition law”, VoxEU.org, 24 July.