The Fed’s monetary policy actions affect inflation and unemployment with a lag typically thought to be around two years in duration. Of course, given the possibility of shocks, it cannot ensure that either inflation or unemployment will be exactly at their long-run levels within that two-year time frame. Both academic and policy economists typically model the Fed as viewing downward inflation (or unemployment) misses as being just as costly as upward misses. In this column, I argue that the Fed’s objective is actually asymmetric, in that it derives material costs (benefits) from overshoots (undershoots).

The resulting trade-off between downward tilts in inflation and unemployment has played a key role in monetary policymaking over the past 14 years.

In a classic 2006 paper, the Norwegian central bank governor Jan Qvigstad offered a simple way to evaluate the appropriateness of the monetary policy decisions in light of possibly competing central bank objectives. Qvigstad argued that monetary policy could only be said to be appropriate if the two-year-ahead forecasts for unemployment and inflation were either both too high or both too low (relative to their longer-run objectives).

What is the logic behind this criterion? Suppose the Fed expected inflation after two years to be too low and unemployment to be too high. Then its policy choices are too hawkish, as easing would facilitate a faster forecasted return of both unemployment and inflation to their long-run levels. Alternatively, if the Fed expected unemployment after two years to be too low and inflation to be too high, then its policy choices were too dovish. (Notice that this logic does not mention forecast errors! We shall see in what follows that this omission is an important one.)

Does the Fed follow Qvigstad’s criterion? To address that question, we can turn to the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).

The SEP is a survey of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting participants (the governors of the Federal Reserve System and the 12 Reserve Bank presidents). It collects their forecasts of the evolution of inflation and unemployment over the next two to three years, and (beginning in April 2009) their long-run forecasts for inflation and unemployment. But these are not forecasts in the usual sense of the word, as they are not conditioned on the policymaker’s outlook for how the FOMC will choose monetary policy. Rather, each participant is asked to base their submission to the SEP on their own individual assessment of appropriate monetary policy. As a result, each participant’s projections for inflation and unemployment can be seen as describing the medium-run and long-run targets for those variables that they are aiming to achieve using the tools of monetary policy.

In a recent working paper (Kocherlakota 2023), I classify the (median) FOMC’s two-year-ahead projections from April 2009 through December 2022 into five color-coded categories.

Purple projection: The projected unemployment rate (UR) is too high and the projected inflation rate is too low. Policy is too hawkish according to Qvigstad’s criterion.

Blue projection: The projected unemployment rate is too high and the projected inflation rate is also too high. This policy stance satisfies Qvigstad’s criterion.

Green projection: Both variables are expected to return to target within two years. This policy stance satisfies Qvigstad’s criterion.

Orange projection: The projected unemployment rate is too low and the projected inflation rate is also too low. This policy stance satisfies Qvigstad’s criterion.

Red projection: The projected unemployment rate is too low and the projected inflation rate is too high. Policy is too dovish according to Qvigstad’s criterion.

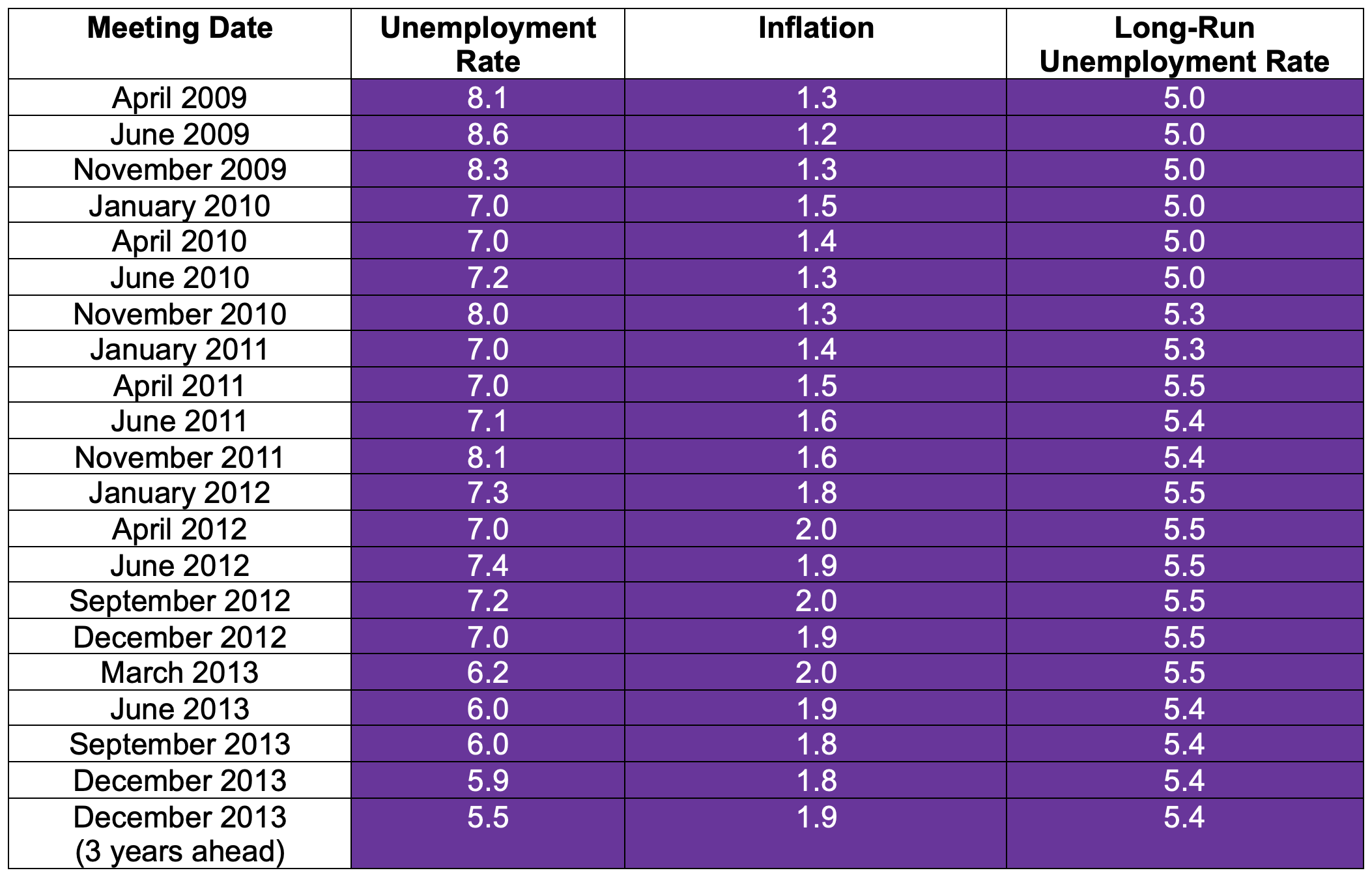

The results of these classifications are depicted in Tables 1-3, where the Tables are distinguished by the relevant chair of the Board of Governors. The Tables and Figure 1 are taken from Kocherlakota (2023). The Bernanke projections are all purple, meaning that they are too hawkish according to Qvigstad’s criterion.

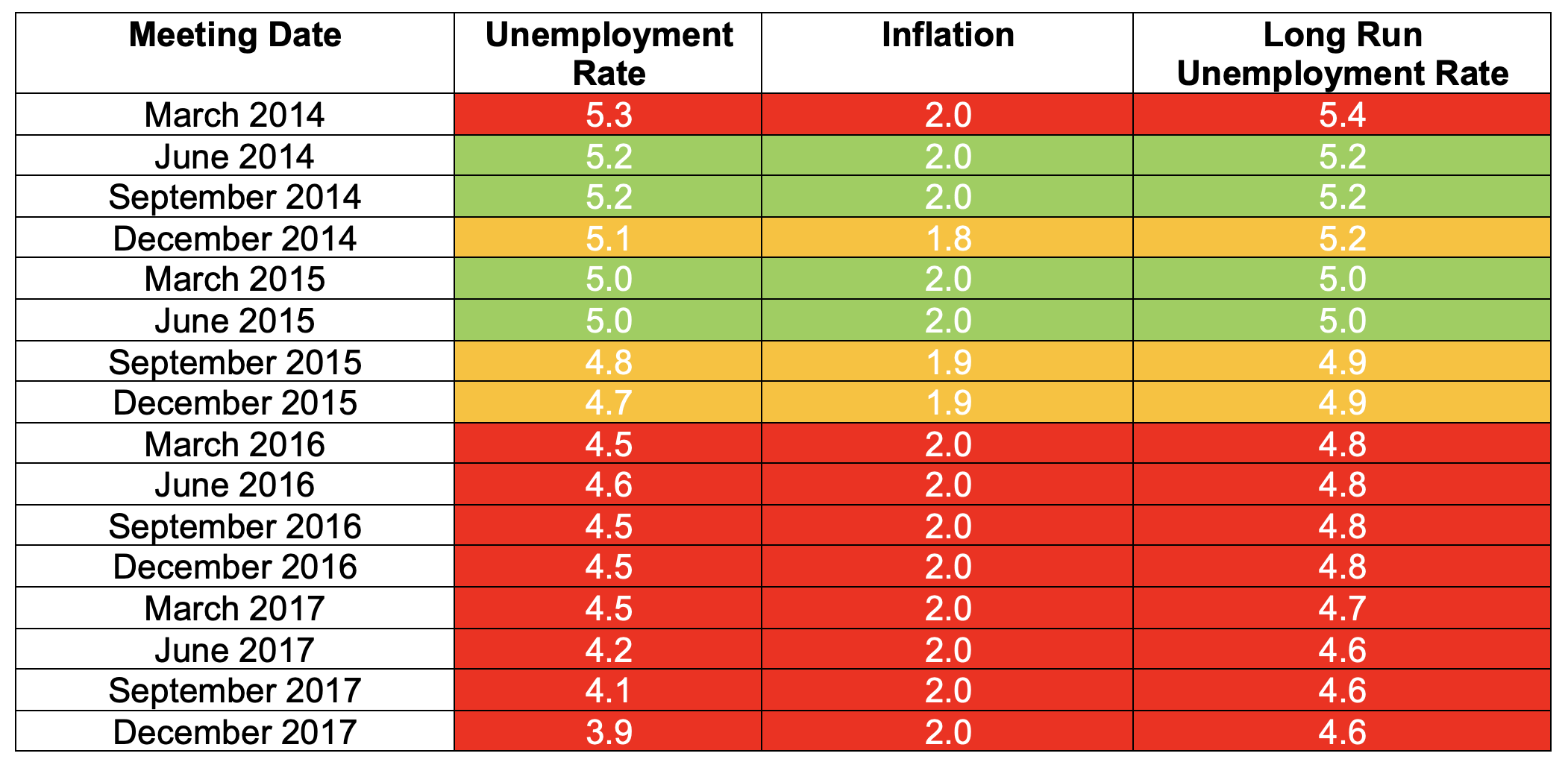

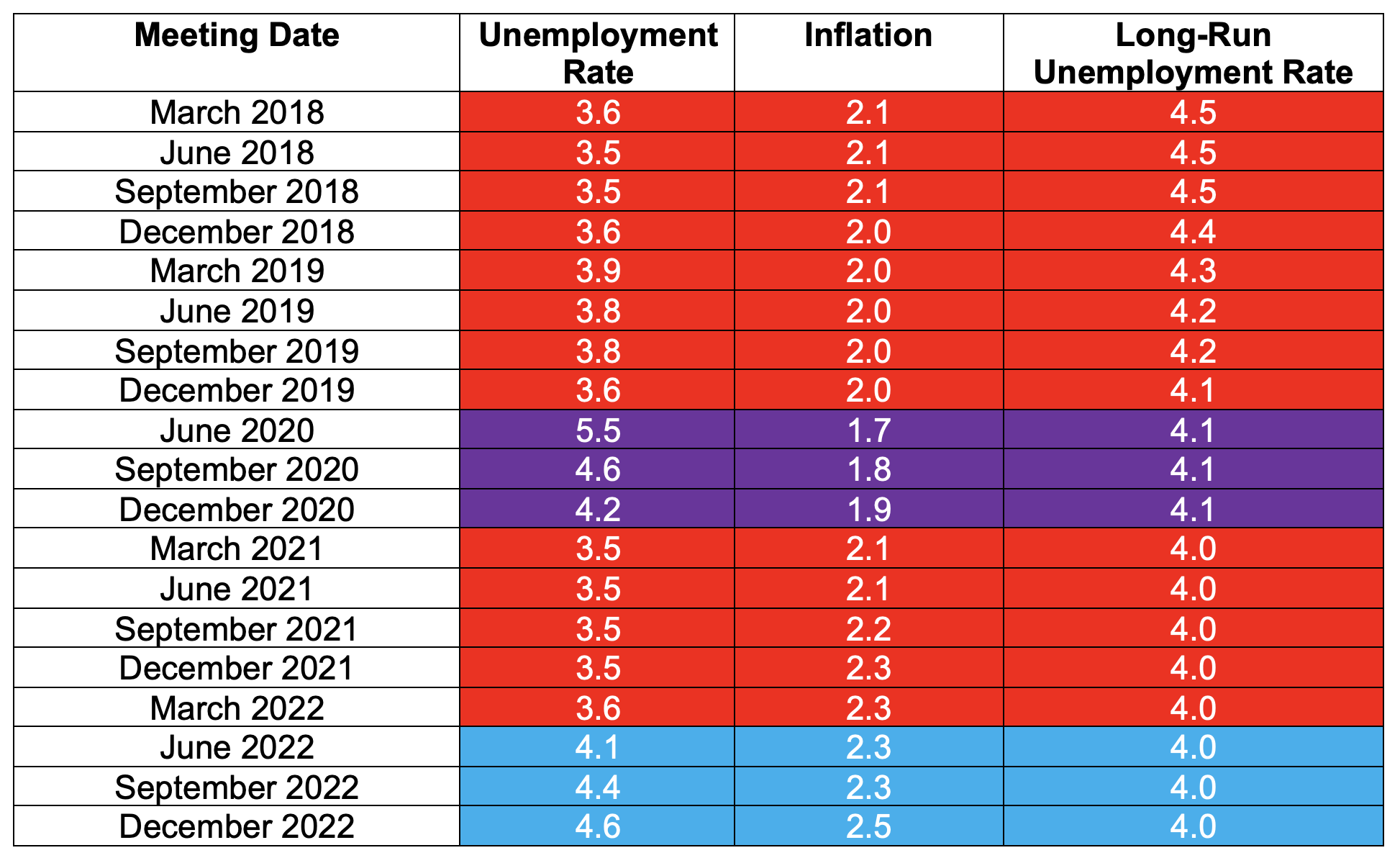

The Yellen projections are often red, meaning that they are too dovish relative to Qvigstad’s criterion. The Powell projections have at times been too dovish (pre-Covid and toward the end of the Covid pandemic) and too hawkish (during the beginning of the Covid pandemic).

Table 1 Median projections from the Bernanke Fed

Notes: These are median projection (from the Survey of Economic Projections) for the fourth quarter unemployment rate (UR) two years ahead, the fourth quarter-to-fourth quarter PCE core inflation rate (inflation) two years ahead, and the long-run unemployment rate (long-run UR). (The median projection for the long-run core PCE inflation rate is 2% at every meeting.) All entries are coded purple, as discussed in the text, meaning that they are more hawkish than the Qvigstad criterion. All medians are based on author’s calculations.

Table 2 Median projections from the Yellen Fed

Notes: These are median projections (from the SEP) for the fourth quarter unemployment rate (UR) two years ahead, the fourth quarter-to-fourth quarter PCE core inflation rate (inflation) two years ahead, and the long-run unemployment rate (long-run UR). (The median projection for the long-run core PCE inflation rate is 2% at every meeting.) They are color-coded as described in the text, so that “red” projections are more dovish than prescribed by the Qvigstad criterion. The medians are based on the author’s calculations for meetings through December 2015 and are included in the post-meetings thereafter.

Table 3 Median projections from the Powell Fed

Notes: These are median projections (from the SEP) for the fourth quarter unemployment rate (UR) two years ahead, the fourth quarter-to-fourth quarter PCE core inflation rate (inflation) two years ahead, and the long-run unemployment rate (long-run UR). (The median projection for the long-run core PCE inflation rate is 2% at every meeting.) They are color-coded as described in the text, so that red projections are more dovish than the Qvigstad criterion and the purple projections are more hawkish than the Qvigstad criterion.

Why does the Fed not adhere to Qvigstad’s criterion? As is standard, the logic behind the criterion (as described above) assumes that the Fed sees unemployment and inflation misses relative to its long-run target as being equally costly whether they are overshoots or undershoots. But the Fed’s choices suggest that it does, in fact, perceive higher costs with respect to inflation overshoots and larger benefits with respect to unemployment undershoots. Under Bernanke’s leadership, the aversion to inflation upward misses led the Fed to aim for low inflation and high unemployment. The Powell Fed repeated that pattern early in the Covid pandemic. Under both Yellen and Powell, the desire for unemployment downward misses led the Fed to aim for (slightly) high inflation and historically low unemployment.

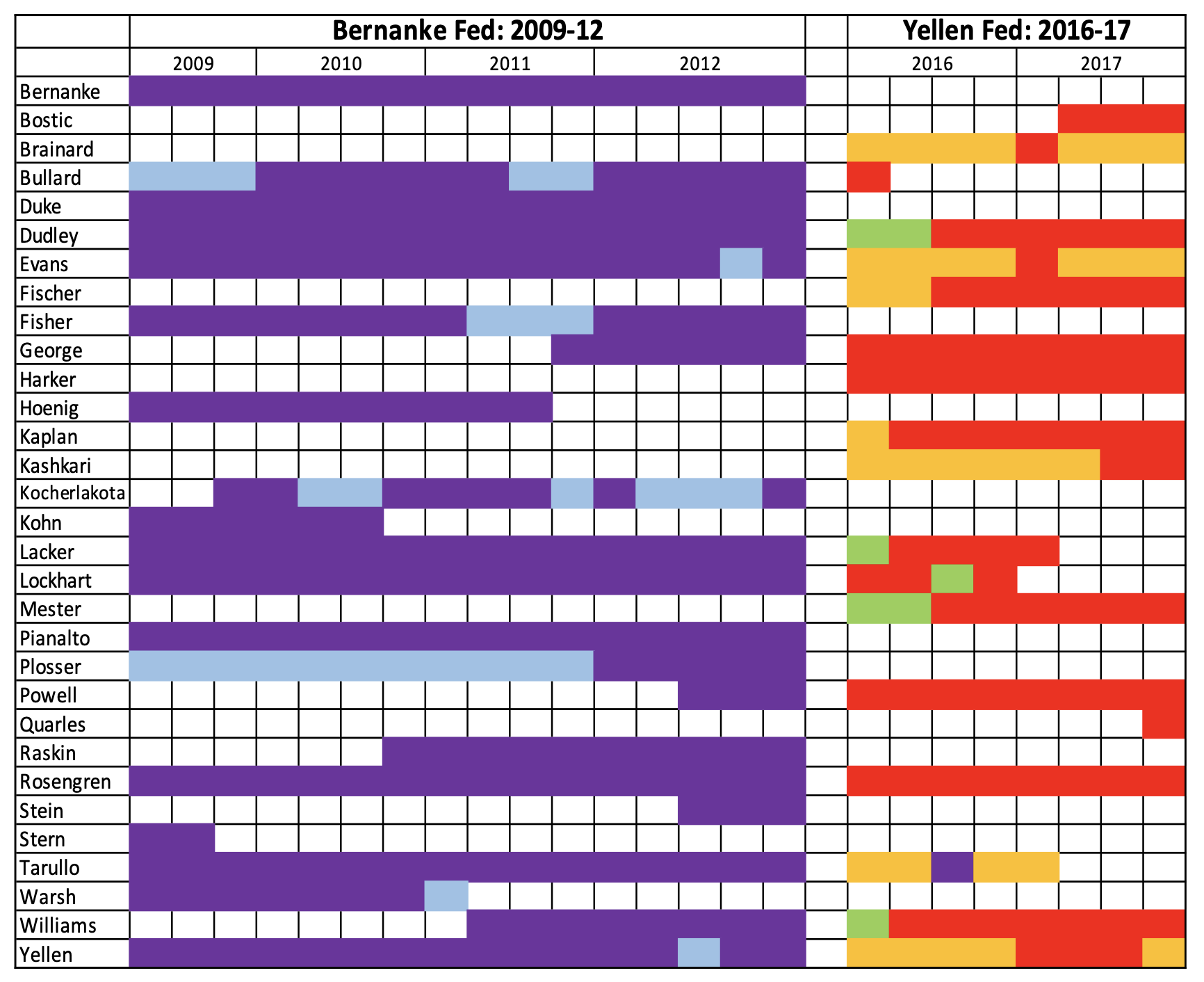

Medians are of course only summary statistics. Figure 1 uses individual-level data from the Survey of Economic Projections. (Unfortunately, the relevant data has not yet been disclosed for the years 2013-15 or the years 2018-22.) The figure documents that almost all of the 11 policymakers who served under both Bernanke and Yellen have at times exhibited aversion to high inflation (purple projections) and at other times a desire for low unemployment (red projections). It seems reasonable to conclude that policymakers are consistently trading off these downward tilts in their objectives in their determinations of appropriate monetary policy.

Figure 1 A panel of projections

Notes: For each meeting at which they submitted projections, a policymaker’s projection is coded as purple, blue, green, orange, and red (as described in the text). Blank spaces mean that the listed policymaker did not submit a full set of projections for the relevant meeting. (James Bullard attended meetings after March 2016 but did not submit long-run projections after that date.) The Fed has not yet disclosed individual-level data for 2013-15. The table omits First Vice Presidents who served temporarily as FOMC participants in the absence of a regional Bank President.

Kocherlakota (2023) discusses the possible sources of these asymmetries and their implications for future research. In terms of inflation, central bankers have expressed concerns that above-target inflation could lead “inflation to become unmoored” (Bernanke 2011) or “inflation to become entrenched” (Powell 2022). That could give rise to the follow-up need to bring down inflation expectations through a severe recession. As Bernanke (2011) says, “the cost of that in terms of employment loss in the future, as we had to respond to that, would be quite significant.” This risk is often discussed informally by both academic and policy economists but is not part of benchmark models of monetary policy. In terms of the labour market, the Federal Reserve sees low unemployment as being a way to generate potentially large gains for demographic groups (such as Black people) who face barriers to employment (Brainard 2020). To the best of my knowledge, there are no macroeconomic models in the academic world that integrate possibilities of this kind.

References

Bernanke, B (2011), “April FOMC meeting press conference”, p. 14.

Brainard, L (2020), “Bringing the statement on longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy into alignment with longer-run changes in the Economy”, 1 September.

Chang, R (2023), “Equality, monetary policy and the central bank mandate”, VoxEU.org, 25 January.

Kocherlakota, N (2023), “Asymmetries in Federal Reserve objectives”, NBER WP 31003.

Powell, J (2022), “Monetary Policy and Price Stability”, Jackson Hole speech, 26 August.

Qvigstad, J (2006), “When does an interest rate path ’look good’? Criteria for an appropriate future interest rate path”, Norges Bank working paper.

Riva, L, J Platzer, S Egiev, A Lin and G Eggertsson (2020), “The Fed’s new policy framework: A major improvement but more can be done”, VoxEU.org, 21 October.

Williams, J (2013), “Forward policy guidance at the Federal Reserve”, VoxEU.org, 16 October.