President Trump is to trade relations what Uber is to licensed taxis: a disruptive, brash force against which rules and conventional practice pale. The Trump administration’s accusations that key trading partners engage in wide-ranging unfair trade practices are difficult to reconcile with claims that the G20’s “no protectionism” pledge has worked.

For supporters of a rules-based trading system, a rogue trading power poses two threats to their world view. The first threat is that the rogue nation decides to openly violate WTO rules and G20 pledges. Only time will tell how far the Trump administration is prepared to go in this regard, although a recent analysis highlighted the potential American protectionism in the pipeline (Bown 2017).

A second, more subtle threat is that fear of US retaliation starts altering the resort to trade distortions by other nations, including other G20 members. If the protection afforded by WTO rules were so strong and fealty to the G20 pledge so entrenched, then one should not see sharp breaks in the resort to trade distortions by America’s leading trading partners. It would be embarrassing if the bluster of the Trump administration tamed G20 protectionism more effectively than established trade norms. In the latest Global Trade Alert report, we present some uncomfortable facts about this matter (Evenett and Fritz 2017).

The data on trade distortions presented here refer to policy instruments implemented between 1 January 2017 and 24 June 2017. So as to place this year’s developments in context, we compare statistics for this year with data on policy choice during the years of the second Obama administration (taken here to be 2013 to 2016). This may reveal whether there have been any sharp breaks in behaviour between this year and prior years when policymakers in Washington DC gave the appearance, at least, of wanting to “play by the rules of the game.”

US policy mix becomes more discriminatory towards the G20

Even though the Trump administration has been in office less than six months, has the abrupt change in trade rhetoric been matched by a shift towards more frequent discrimination in favour of US commercial interests? The simple answer is yes.

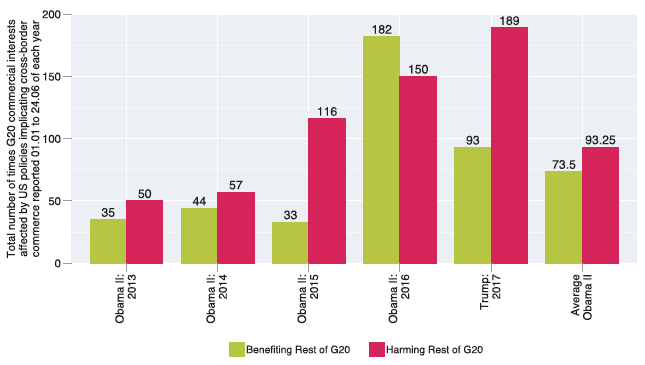

Figure 1 reports for each year since 2013 (the first year of the second Obama administration, ‘Obama II’) the total number of times that US policy interventions have harmed and have benefited the commercial interests of the other G20 members. Resort to discrimination against the commercial interests of other G20 members grew year on year through the Obama II administration, reaching 150 instances of harm implemented between 1 January and 24 June 2016. Between the same dates in 2017, however, the US implemented policy actions that harmed the commercial interests of fellow G20 members 189 times, a jump of 26%.

Figure 1 More discrimination, less liberalising policy intervention than Obama II

With the exception of 2016, during the Obama II years relatively few steps were taken by US government agencies that benefited G20 trading partners. In 2016, the number of times the G20 benefited from US actions actually exceeded the number of times they were hurt. In the year to date, however, the number of times G20 trading partners have gained from US policy intervention has halved.

A comparison between the columns in Figure 1 for 2016 and 2017 points clearly to the conclusion that US policy mix in the past six months has shifted markedly in a beggar-thy-neighbour manner. And please note this data was compiled before President Trump decides what to do about the investigations he has asked for into steel imports and trade with China.

Meanwhile, G20 hits to US commercial interests fell 29%

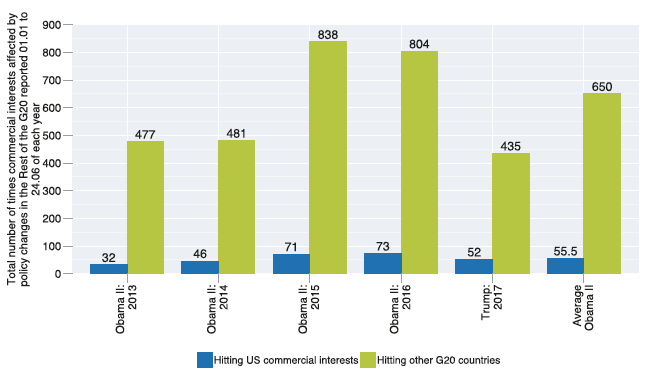

While the US was titling the commercial playing field even further against trading partners, the opposite was happening in the rest of the G20. As Figure 2 shows, the number of times that the rest of the G20 hit US commercial interests kept growing during the second Obama administration, reaching a total of 73 hits during 1 January 2014 to 24 June 2016. However, over the comparable time period this year, that total fell just over a quarter to 52 hits.

Figure 2 The rest of the G20 inflicted far fewer hits on each other’s commercial interests in 2017

The smaller number of hits to US commercial interests coincided with less resort to protectionism by the rest of the G20. So far this year, the rest of the G20 has hit the commercial interests of other members of that group (excluding the US) a total of 435 times, down 45% on the comparable period in 2016.

Are any G20 members defying Washington?

Of course, G20 members differ and so it is worth examining whether there are any interesting differences across the US’ G20 partners in the resort to protectionism during the year to date. Given the emphasis that the Trump Administration has put on bilateral trade deficits, did G20 trading partners with the largest trade surpluses with the United States cut back on protectionism the most in 2017? Or were the cuts larger in the G20 members that have imposed more measures harming US commercial interests in the years before the Trump administration and so may feel they are a bigger target for retaliation?

To explore these matters, we computed for each G20 member government (other than the US) the average number of times they implemented policy instruments harmful to US commercial interests during 1 January and 24 June of each year of the second Obama administration. This provided a benchmark for each G20 member against which their resort to protectionism harming US interests in 2017 can be compared.

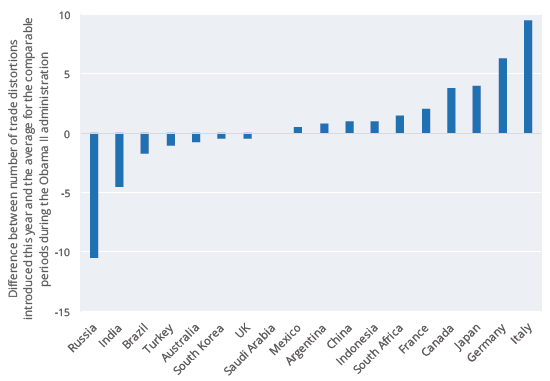

Figure 3 reports the difference between the number of times a G20 member imposed measures that harmed US interests in 2017 and during the second Obama administration. The G20 members are ranked in ascending order from left to right in terms of that difference. A negative difference implies that the G20 cut the number of policy instruments harming US interests in 2017.

Figure 3 During 2017 hits to US commercial interests from the large emerging markets fell – in contrast to Canada, Japan, Germany, and Italy

Correlation plots (that can be found in the report) show that G20 members that reduced their hits to US interests the most this year were those governments whose policies hit US firms and workers most often the during years 2008-16. Whereas G20 members with the largest trade surpluses have not tempered their resort to protectionism, if any, the reverse.

These findings are not inconsistent with the argument that some G20 members may have decided that discretion is the better part of valour. That is, knowing how vulnerable they were to criticism for past protectionism, some of the G20 may have curbed their protectionist zeal this year. This begs the awkward question: has President Trump’s bluster accomplished what the G20 pledge failed to deliver – namely, less protectionism? So far, the data can’t rule that out.

The G20’s protectionist chickens come home to roost

All too often, trade diplomats and G20 officials have denied the importance of beggar-thy-neighbour policies since the onset of the global economic crisis. This is not the place to speculate as to why they did so. Instead, the focus is on the potential consequences of this denial.

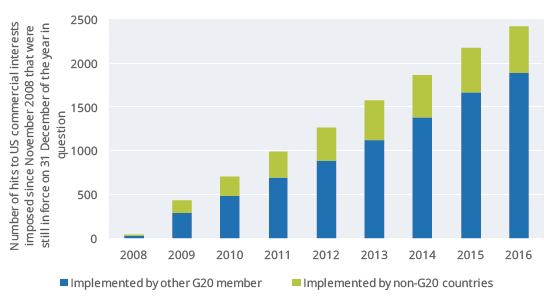

The most important of which is that, should President Trump and his team decide to wage an all-out assault on foreign trade distortions, then there is enough publicly available information to build such a case. For example, Figure 4 shows the number of foreign trade distortions in force at the end of each year since the crisis began. Those totals have risen sharply over time. At the end of 2016 the total number of crisis-era protectionist measures that harmed US commercial interests which were still in force was 2,420. The rest of the G20 was responsible for 1,883 of them.

Figure 4 The G20’s failure to curb protectionism provides President Trump with plenty of ammunition to blast trading partners

Return to a power-based trading system?

In sum, fear, it seems, trumped trade rules and G20 pledges when it came to taming protectionism in the first half of 2017. This finding will be uncomfortable to some as it could presage a return to a power-based trading system. Still, the realisation that the G20 protectionist chickens have come home to roost could spur more open and constructive discussion about the limits of “binding” trade rules and G20 pledges in defending open borders during an era of sub-par growth and geopolitical rivalry.

References

Bown (2017), “Trump Is a New Kind of Protectionist—He Operates In Stealth Mode”, Peterson Institute, 12 June.

Evenett, S and J Fritz (2017), Will Awe Trump Rules? The 21st Global Trade Alert Report, CEPR Press.