The pandemic spurred extraordinary government efforts to protect lives and livelihoods. In OECD countries, these efforts have included a historic expansion of welfare states, a massive distribution of vaccines, and broad requests – sometimes demands – to restrict movement and activities to prevent the spread of the virus. The extensive reach of the state during the pandemic has led to media pronouncements on trust in government that range from ‘rally around the flag’ explanations for periods of high trust

to ‘trust is in crisis’ proclamations when governments are seen as performing poorly.

But looking beyond the headlines, trust between citizens and their government has proven to be a critical factor in addressing the COVID-19 crisis (Algan et al. 2022, Bargain and Aminjonov 2020a, 2020b). Trust in government depends on many factors, both at the individual and societal levels. A long-standing literature looks at the performance and reputation of institutions as important and independent factors contributing to trust (Bouckaert 2012, Van de Walle and Migchelbrink 2020) and, similarly, OECD work has focused on measuring to what degree, and how, governments’ reliability, responsiveness, openness, integrity, and fairness affect people’s confidence (OECD 2017).

Understanding these drivers of trust became even more important as the pandemic occurred against a backdrop of ongoing concerns about the ability of democratic governments to address globalisation and digitalisation, steer the needed green transformation of our societies, and maintain social cohesion in the face of growing political polarisation. Our more recent work therefore contributes to unpacking the links between public trust and democratic governance, to help countries identify effective responses to shocks and strengthen their democratic governance models to tackle major challenges.

The inaugural OECD Survey on Trust in Public Institutions (‘Trust Survey’) helped us take a big step in our understanding of how trust works. This nationally representative survey interviewed over 50,000 respondents in 22 OECD countries in late 2021 to understand what drives public trust in democracy government (OECD 2022).

Results vary across countries, as expected, due to different survey timings but also because of different cultural, institutional, and economic factors. Yet, some general results hold for all OECD countries and reveal common public governance challenges that countries face as they try to strengthen trust and democracy.

What did we find?

People in OECD countries have confidence in government reliability

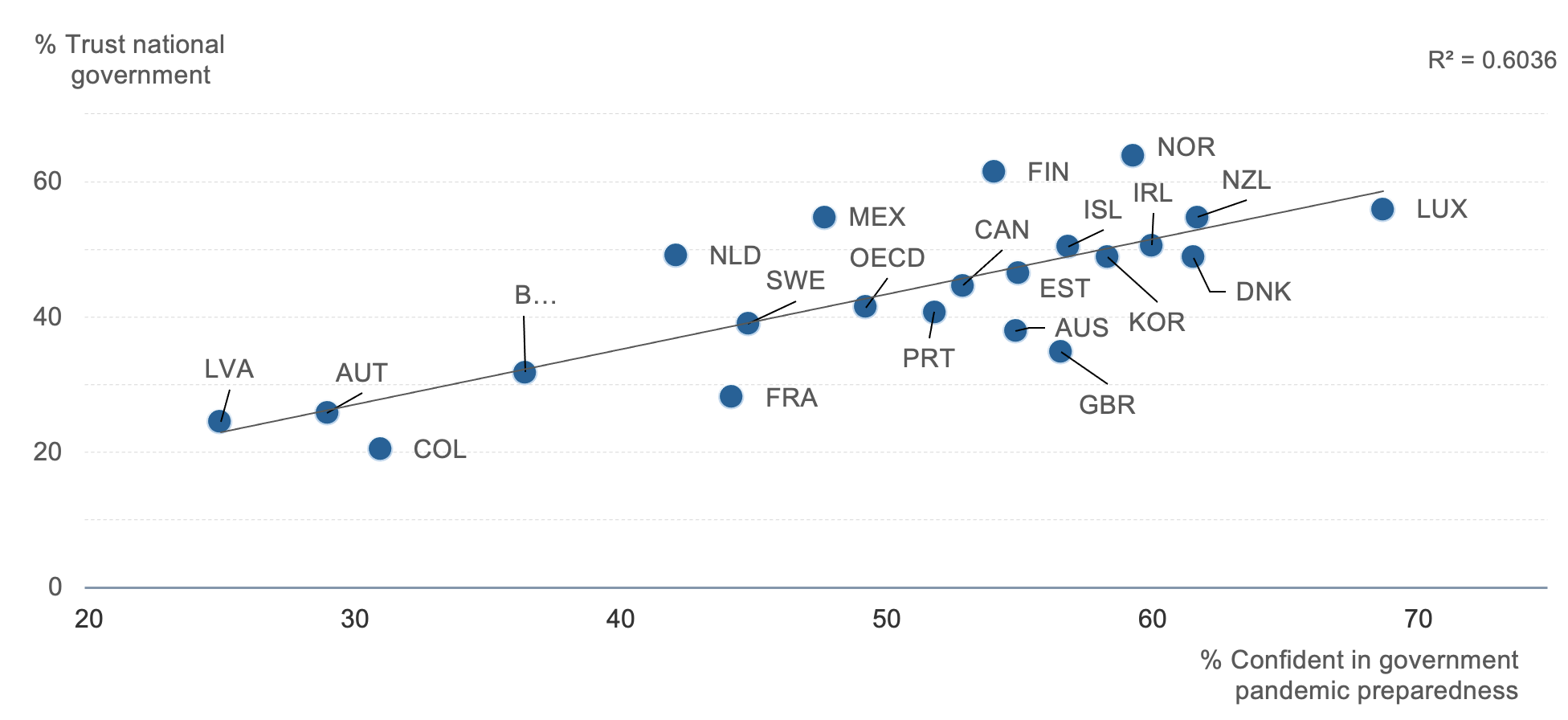

People have reasonably high confidence that their government will be prepared for a future pandemic, and confidence in pandemic preparedness is positively associated with trusting the national government (Figure 1). On average across countries, 49% of respondents express confidence that their government would be prepared to protect people’s lives in the event of a new pandemic, and only about one-third (33%) say their government is unlikely to be prepared. Given the enduring human and economic costs of the pandemic, and the amount of information a typical person acquired about public health over the past two years, this positive expectation is a noteworthy outcome. It suggests that people see governments as having learned from the information gained during this experience.

Figure 1 Positive perceptions of preparedness for a future pandemic are associated with higher trust in the national government – and vice versa

Share of respondents reporting high trust in national government and share of respondents who consider it likely that the government institutions will be prepared to protect people’s lives in the event of a future pandemic, 2021

Note: For Mexico and New Zealand, trust in civil servants is used in lieu of trust in the national government as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government. For more information on the survey method see Nguyen et al. (2022).

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust).

We also see fairly high satisfaction with national healthcare, educational systems, and administrative services, even after two years of strain induced by the health crisis.

But respondents are more sceptical of governments’ reliability to address long-term challenges, such as climate change

The survey finds a discrepancy between public attitudes towards climate policies and confidence in the success of these policies. On average in the OECD, about half of respondents (50.4%) think that the governments should prioritise actions related to climate change, while only about a third (35.5%) are confident that governments will succeed in reducing their country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Concerns about the effectiveness of policies may explain this result (Stantcheva et al. 2022), as well perceived reliability of policy commitments to tackle global and intergenerational challenges.

The role of trust in building public support for long-term policies with intergenerational trade-offs has been documented and investigated empirically (Fairbrother et al. 2021, Brezzi et al. 2021). Analysis from the trust survey finds that investing in public governance to deliver more effective policies to fight climate change may pay off in securing more credibility and trust in government. Those who are confident that their country will succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions are more likely to trust the government. This relationship holds also at the country level, with a strong and positive relationship between confidence in reducing climate change and trust in the national government and, to a less extent, local government, and civil servants.

People view government as not responsive enough, with opportunities for representation and participation in decision-making as falling short of their expectations

We also find, across various survey questions, widespread scepticism that government responds to public feedback. Only about four in ten respondents, on average across countries, say that their government would improve a poorly performing service, implement an innovative idea, or change a national policy in response to public demands. And fewer than one-third of respondents believe that the government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation (Figure 2). There are also concerns that political officials are captured by special interests. Almost half of respondents (48%), on average across countries, say it is likely that a high-level political official would grant a political favour in exchange for the offer of the prospect of a well-paid job in the private sector.

Perceptions of low responsiveness and real opportunities for engagement are two factors that appear consistently across countries to explain why trust is under strain.

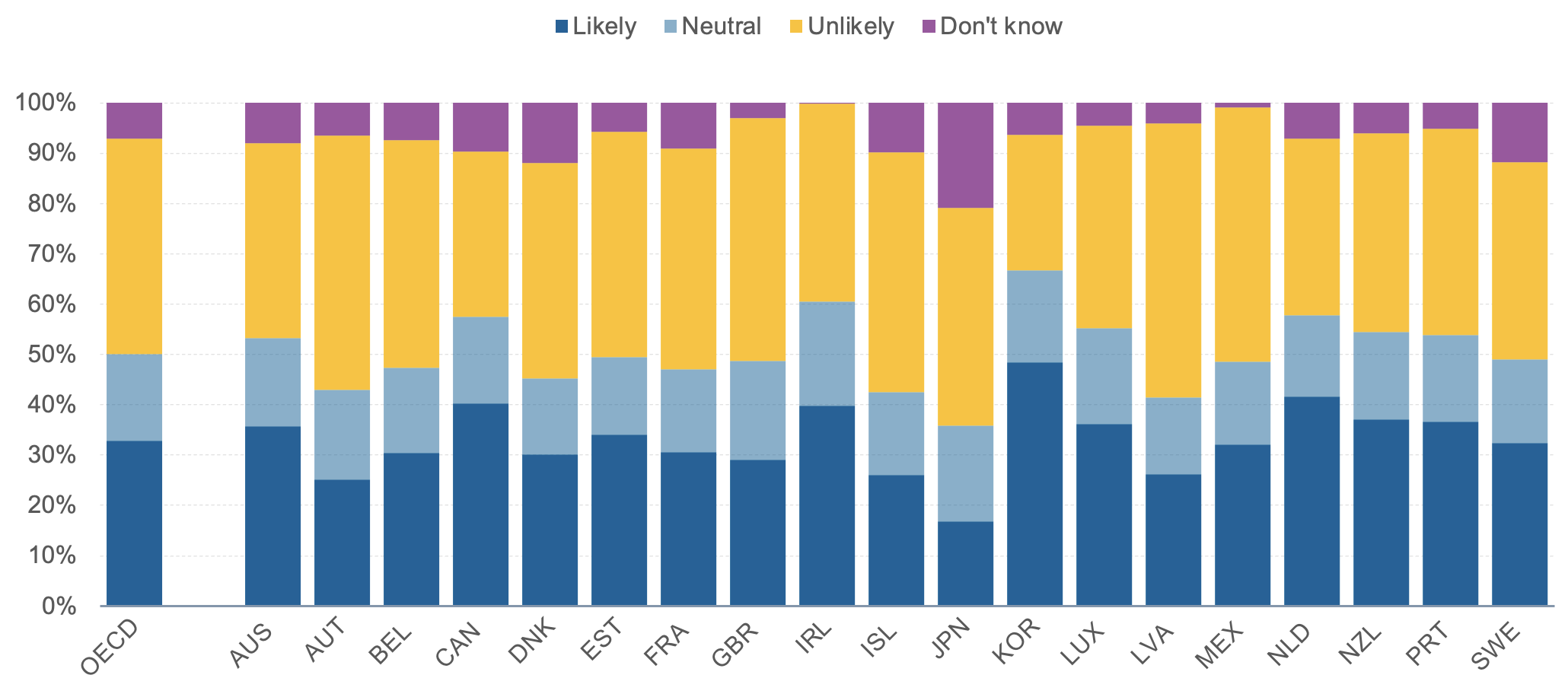

Figure 2 Very few think that the government would adopt views expressed in a public consultation

Share of respondents who indicate different levels of perceived likelihood that a government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation (on a 0-10 scale), 2021

Note: In Mexico, the question was formulated in a slightly different way. Finland and Norway are excluded from the figure as the data are not available. For more information on the survey method see Nguyen et al. (2022).

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Vulnerable groups have less trust in government, and most people worry about equal opportunities

Reflecting inequalities that preceded the pandemic, the Trust Survey finds that young respondents with low levels of education, and those with low incomes report markedly lower levels of trust in government than other groups. Perceptions matter, too – trust in government is noticeably lower for people who feel financially insecure, or who feel that they have a low social status (Figure 3).

Many people worry about equal treatment by government and equal opportunities to participate in politics. Few feel they have a way to participate meaningfully in democratic political processes. For example, on average across countries, 50% of people say the political system in their country does not allow people like them to have a say in what government does. Lack of political voice, feelings of inability to participate in politics, and political polarisation matter to explain much lower levels of trust (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Feelings of insecurity correspond with lower trust in government

Share of respondents that report trusting the national government by level of respondents’ vulnerability, socioeconomic and demographic factors, 2021

Note: OECD unweighted proportion of respondents that report to trust the national government (response categories 6-10) by whether they feel they have a say in what the government does, they voted for parties currently in power, self-reported social status, own ability to participate in politics, self-reported financial security, education attainment, levels of income (top and bottom 20% of national income distribution), and age (less than 30 years old and more than 50 years old). For more information on the survey method see Nguyen et al. (2022).

Source: http://oe.cd/trust

So, what can governments do?

It is time to move beyond the headline numbers and focus on what governance factors matter most for building trust in government and reinforcing democratic institutions. Trust Survey data can help.

Analyses of the OECD Trust Survey data suggest that governments must continue improving their reliability and preparedness to future crises, designing policies and public services with and for people, and enhancing transparency and communications to citizens around promises and results. These factors matter for trust, and there is room for improvement and learning across and within countries in these areas. Governments must also recommit to engaging with citizens in policy design, delivery, and reform; safeguard and enhance people’s ability to exercise their effective political voices; ensure the integrity of elected officials; continuously measure and improve public service delivery; and do more to ensure the inclusion of vulnerable and marginalised groups.

The future of effective governance – and trust in government – depends on doing this better.

References

Algan, Y, D Cohen and M Péron (2022) “Trust: The other factor in the Covid-19 crisis”, VoxEU.org, 2 February.

Bargain, O and U Aminjonov (2020a), “Trust and compliance to public health policies in the time of COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 23 October.

Bargain, O and U Aminjonov (2020b), “Trust and compliance to public health policies in the time of COVID-19”, Journal of Public Economics 192: 104316.

Bouckaert, G (2012), “Trust and public administration”, Administration 60(1): 91-115.

Brezzi, M, S González, D Nguyen and M Prats (2021), "An updated OECD framework on drivers of trust in public institutions to meet current and future challenges", OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Fairbrother, M, G Arrhenius, K Bykvist and T Campbell (2021), “Governing for Future Generations: How Political Trust Shapes Attitudes Towards Climate and Debt Policies”, Frontiers in Political Science 3.

Nguyen, D, V Frey, S González and M Brezzi (2022), "Survey design and technical documentation supporting the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions", OECD Working Papers on Public Governance,OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Stantcheva S, A Dechezlepretre, A Fabre, B Planterose and A Sanchez Chico (2022) “Fighting Climate Change: International Attitudes Toward Climate Policies”, NBER Working Paper 30265.

Van de Walle, S and K Migchelbrink (2020), “Institutional quality, corruption, and impartiality: the role of process and outcome for citizen trust in public administration in 173 European regions”, Journal of Economic Policy Reform 25(1): 1-19.