The consumption of energy is associated with numerous negative externalities. Fossil fuels, specifically, cause emissions of CO2, the most prevalent greenhouse gas. With the issue of climate change far from resolved, understanding the determinants behind emission levels is necessary to improve forecasting and guide policy making.

There is ample empirical evidence that energy demand depends on per capita income. In high-income countries, a number of single-country survey-based studies find that rich households spend a smaller share of their income on energy (e.g. Dubin and McFadden 1984). Less is known about this relationship in the developing world, where most of the growth in energy demand is currently taking place. A number of studies find that energy demand also increases slower than total expenditures in middle-income countries, including in China (e.g. Cao et al. 2016). On the other hand, as large populations are just beginning to purchase energy-intensive appliances (fridges, air conditioners, cars), it is feared that energy demand in the developing world may keep growing rapidly (Auffhammer and Wolfram 2014, Gertler et al. 2016).

More generally, the structural change literature has clearly documented that consumers of different income levels prefer different sets of goods (e.g. Comin et al. 2018), generally shifting from agriculture to manufacturing to services as income grows. Yet we still do not have a clear picture of the aggregate consequences for energy consumption, and what the relationship between income, consumption patterns and CO2 emissions looks like in the aggregate. This relationship directly affects the CO2 intensity of GDP, a critical ingredient when trying to project emissions and understand the potential magnitude of climate change. A quick survey of prominent emission projection models (from academics, governments, or international agencies) also shows that these models tend to incorporate income effects in consumption in a rather crude manner, as they are typically more focused on technology assumptions.

Our recent article (Caron and Fally 2018) systematically summarises the implications of shifting consumption patterns on energy demand and emissions. We take an aggregate view across countries spanning most of the per capita income spectrum and all sectors of the economy. Our framework, an extension of the general equilibrium model described in Caron et al. (2014), links non-homothetic household preferences (i.e. with non-trivial income effects) to emissions through production and trade linkages. The model allows us to uncover patters of comparative advantage in the production of CO2-intensive goods. We can thus identify the role of income in determining energy demand, making sure that we are not confounding it for differences in the availability of energy or energy-intensive goods and services across countries.

The relationship between income elasticity and emissions intensity across sectors

Do high income consumers prefer goods which are, coincidentally, less CO2 intensive in their production?

Using different types non-homothetic preferences, we estimate the income elasticity of goods in 50 sectors of the economy. As many before us, we find a clear role for per capita income in determining consumption patterns – the income elasticity of most sectors is significantly different from one.

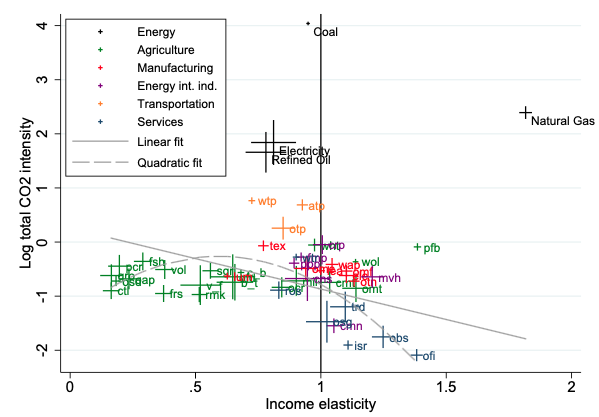

The directconsumption of energy generally increases slower than income. Figure 1 shows that the two main energy goods consumed directly by households, electricity (ely) and refined oil (p_c, mostly gasoline for transportation), have an income elasticity below one. While these estimates reflect an average across all countries, they depend on income – energy consumption is more income-elastic in low-income countries. This is consistent with scattered country-level evidence from the literature.

Figure 1 The inverted-U/negative relationship between income elasticity and (log) CO2 intensities at the sector level

Notes: Each marker represents a sector of the economy; Marker size reflects the sector's average share of final demand. Total CO2 intensity represents the total amount of CO2, in kg, associated with the consumption of a dollar of each good; grey lines represent the fit of linear and quadratic regressions;Both the negative and inverted-U relationships are significant at the 1% level. See Caron and Fally (2018) for full list of sectors.

However, just looking at direct energy consumption is misleading. It ignores the emissions embodied in the consumption of non-energy goods – think of the emissions caused by the production of the steel and leather constituting the chair you are sitting on, and so on. Tracking ‘indirect’ emissions throughout global supply chains (based on intermediate input and trade linkages), we can compute the ‘total’ emissions associated with the consumption of each good. Plotting income elasticity against total (embodied) CO2 intensity, Figure 1 reveals an ‘inverted-U’ relationship – sectors of intermediate income elasticity have, on average, the highest CO2 intensity. But it is also asymmetric and negative overall, with high-income-elasticity sectors having the lowest CO2 requirements on average.

We insist that this represents an ‘incidental’ correlation – high-income consumers do not necessarily prefer these goods becausethey are less emissions intensive.

Explaining cross-country differences in consumption-related emissions

Does this systematic relationship between income elasticity and CO2 intensity add up to important differences in CO2 emission levels across countries?

In contrast to a number of other pollutants, CO2 emissions tend to keep increasing with income. However, a number of studies have found emissions per capita, and emissions per dollar, to peak at middle-income levels (Dietz and Rosa 1997, Schmalensee et al. 1998), a variant of the ‘environmental Kuznets curve’.

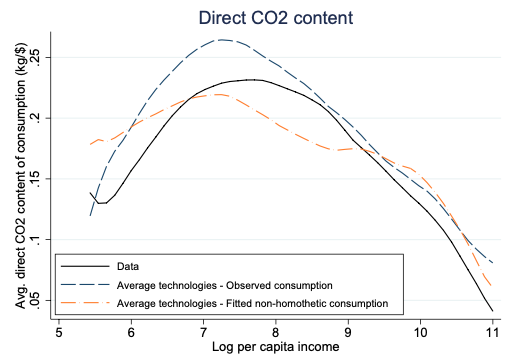

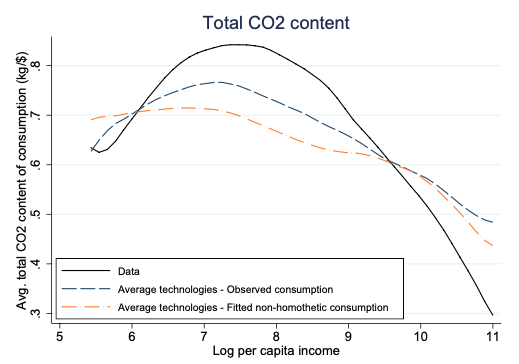

As we focus on consumption, we start by documenting a similar relationship between income and the average CO2 embodied in each dollar of consumption: the black solid lines in Figure 2 reveal a distinct asymmetric inverted-U relationship between per capita income and both the direct and total average CO2 contents of consumption. While lower-middle-income countries have the most emission-intensive consumption baskets, the relationship is also negative overall – high-income countries have the lowest intensities.Similarly to previous environmental Kuznets curve studies, though, this finding is purely descriptive and cannot be used to infer anything about how emissions will evolve as incomes grow.

Figure 2 Average CO2 content across countries

Note: lines represent local linear regression smoothing of country-specific values.

To isolate the role of differences in consumption choices, we re-calculate consumption emissions using the same (weighted average) sector-level CO2 intensity coefficients in all countries. Doing so neutralises differences in production technologies across countries, within-sector heterogeneity (types of goods, differences in quality), and the role of trade (the sourcing of goods). We find that differences in consumption patterns alone explain 33% of total cross-country variability in the total CO2 intensity of consumption baskets. They also generate a relationship in which high-income countries have the least emissions-intensive consumption (seethe blue dashed line of Figure 2).

To isolate the role of income in explaining these differences in consumption patterns, we once again re-compute consumption emissions with the estimated fitted consumption shares that come out of our model. These vary across countries only because of non-homothetic behaviour (because of income) and partially replicate observed patterns, including the fact that emissions intensities decrease with income (see the orange dashed line in Figure 2). The finding that higher income leads consumers to prefer less emission-intensive goods complements recent research from Levinson and O’Brien (2018). Using a related structural approach, they have documented for the US that the indirect consumption of criteria pollutants (local pollutants, in contrast to CO2 which is global) increases slower than income.

However, and importantly, while there is a role for income in determining both the direct and total CO2 content of consumption, it is also clear from Figure 2 that differences in income lead to proportionally smaller differences in total than in direct consumption emissions.

Income-driven changes in consumption habits are no silver bullet for the climate change problem

Having established per capita income as a determinant of CO2intensity, we estimate the scope for consumer-driven movements away from emissions-intensive sectors to decarbonise the economy, even absent any improvements in technology.

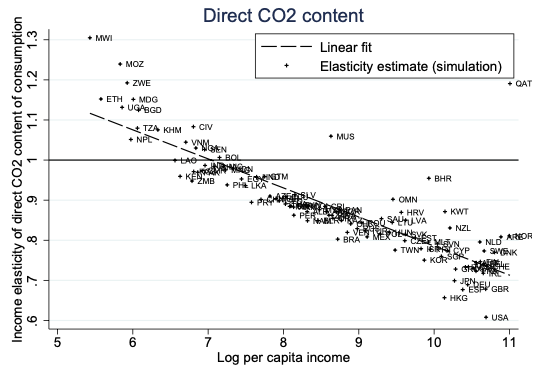

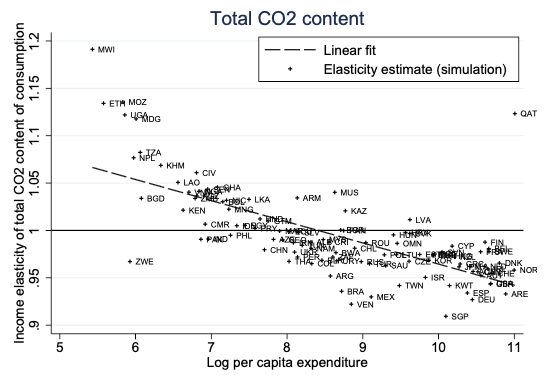

To do so, we simulate income growth in all countries. Our general equilibrium model considers not only how consumption patterns will change but also the adjustment of production and trade patterns. We do not intend this to be a projection exercise, simply one that allows us to highlight the role of consumption patterns. Figure 3 shows simulation results for each country, expressed as the income elasticity of consumption emissions. A value of 1 implies that the country’s emissions would increase proportionally to per capita income. Estimated elasticities clearly depend on income – they are lowest in high-income countries but above 1 in low-income countries. But overall, the ‘income effect’ is negative. For the direct consumption of energy (top panel), emissions decrease in all but the lowest-income countries such that in total over all countries, a 1% increase in income increases emissions by only 0.88%. This result is based on the use of a plausible but conservative value of fossil fuel supply elasticity; more elastic supply gives a stronger demand effect.

Figure 3 The simulated elasticity of the CO2 content of consumption to per capita income

Notes: general equilibrium estimates; fossil fuel supply elasticity calibrated at 0.75.

Looking at income’s effect on the total CO2 content of consumption baskets (bottom panel), however, confirms that income effects are overall weaker – even though values are once again lower for high-income countries, they are above one for a larger set of countries. We find that a 1% increase in income would increase emissions by a close-to-proportional 0.96% worldwide. This is of course the metric of interest, being closely tied to total emissions

We conclude that demand-side forces are pushing in the right direction overall. Yet their effect is modest overall, as estimates suggest a period of increasing emissions intensity in low-income countries as well as a shift from direct to indirect consumption of energy. Consumption-driven decarbonisation will not substantially contribute to solving the climate change problem in the short run.

References

Auffhammer, M and C Wolfram (2014), “Powering Up China: Income Distributions and Residential Electricity Consumption”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 104(5): 575-80.

Cao, J, M S Ho, H Liang et al. (2016), “Household energy demand in Urban China: Accounting for regional prices and rapid income change", The Energy Journal 37 (China Special Issue).

Caron, J and T Fally (2018), “Per Capita Income, Consumption Patterns, and CO2 Emissions”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13092.

Comin, D, D Lashkari and M Mestieri (2015 – updated in 2018), “Structural change with long-run income and price effects”, NBER Working Paper 21595.

Dietz, T and E A Rosa (1997), “Effects of population and affluence on CO2emissions”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94(1): 175-179.

Gertler, P J, O Shelef, C D Wolfram and A Fuchs (2016), “The Demand for Energy-Using Assets among the World's Rising Middle Classes", American Economic Review 106(6): 1366-1401.

Levinson, A and J O'Brien (2018), “Environmental Engel Curves: Indirect Emissions of Common Air Pollutants", The Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Schmalensee, R, T M Stoker, and R A Judson (1998), “World carbon dioxide emissions: 1950-2050", Review of Economics and Statistics 80(1): 15-27.