While numerous studies have analysed the effect of central bank communication and transparency on the financial markets (for example Altavilla et al. 2020), less effort has been placed on the analysis of their effect on the public at large (Blinder et al. 2008). Recent strands of literature address aspects of communication with the general public. Using Dutch survey data, Van der Cruijsen et al. (2015) report that the public’s knowledge of monetary policy objectives is far from perfect and varies widely across respondents. Binder (2017) documents gaps in households’ ‘informedness’ that may limit receptiveness to central bank communications. Some potential listeners may not be interested in what is communicated to them (Blinder 2018) and others may be overwhelmed by the complexity of content and language. Haldane and McMahon (2018) note that despite a rapid growth in central bank communication, the general public has largely remained a blind spot for these communications. Ter Ellen et al. (2020) show how central bank communication reaches the general public via news media coverage on topics relevant for monetary policy decisions.

In recent work (Hwang et al. forthcoming), we investigate the effect central bank speeches have on business executives’ opinions of their central banks’ impact on the economy. The panel includes 61 countries and covers the period from 1998 to 2016.

The importance of managers’ perceptions

Managers’ perceptions of the economic impact of their central banks are important for several reasons. First, a central bank considered to have a positive effect on the economy will have support for its decisions necessary for fulfilling its mandates. Second, the establishment of trust and credibility are the preconditions of central bank independence. After all, only a successful central bank will enjoy support of its independence. Third, since such a central bank will be more credible, it will more successfully steer agents’ expectations (Duca-Radu et al. 2021). Fourth, knowing how the public perceives policymakers’ decisions allows them to identify associated problems and take adequate remedies.

The IMD survey

Our panel analysis uses as an endogenous variable the survey conducted by the Institute for Management Development (IMD), a Swiss-based international business school. The specific item of the survey on which we relied is “Central bank policy has a positive impact on economic development.” A major advantage of the survey that is particularly appropriate for tackling our research question is that it is addressed to respondents with higher and comparable education levels for whom individual socioeconomic characteristics are less relevant. As can be inferred from Figure 1, the average value (the thick red line) exhibits a gradual declining trend until 2016, with drops occurring in 2001 and 2008, coinciding with the collapse of the dotcom bubble and the Global Crisis.

Figure 1 IMD Survey: “Central bank policy has a positive impact on economic development.”

Notes: The IMD survey collects responses by business managers to the statement “Central bank policy has a positive impact on economic development.” A value of 10 means “agree”, while 0 indicates that the respondent “disagrees” with the statement. Each grey line represents a country’s average values over time. The orange line shows the cross-country median, and the red line shows the cross-country average of the 61 countries in our sample.

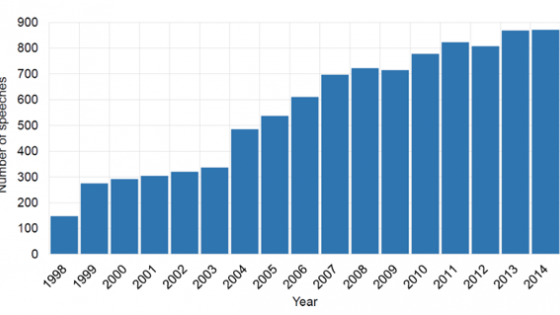

Figure 2 plots the number of speeches given by the central banks included in our country sample during the period 1997 to 2018, distinguished by governors and other board members. As the figure suggests, central banks began to intensify their speaking activities before the Global Crisis. We further observe that speaking activities do not increase at particular times, such as periods of heightened uncertainty (measured by the VIX). Figure 2 also shows that the share of speeches given by governors has decreased over the years.

Figure 2 Number of speeches per year (all central banks) and uncertainty

Quantity of speeches

We find compelling evidence that intensive central bank communication, as measured by the quantity of speeches, worsens the central bank’s economic impact as perceived by managers from FE panel and GMM estimation results. During the Global Crisis, the negative effect even strengthened. This is surprising given that more communication is especially important to informing the public, and business executives in particular, in times of uncertainty.

Speakers’ identity

However, it is not just the quantity of speeches that matters but, crucially, also the identity of the speakers. A closer inspection revealed that the negative effect on executives’ assessments is generally attributable to speeches by board members other than the governor. During the Global Crisis the negative impact of non-governor speeches on managers’ opinion even worsened. In contrast, governors’ speeches had a favourable effect.

Heterogeneity across countries: Exchange rate regime and policy mandates

Next to speakers’ identity, the exchange rate regime also plays a role. While the effect is negative under a free-floating exchange regime, it is positive under a crawling peg and a managed floating regime. Central bank mandates also make a difference. In countries with an explicit employment objective, making more speeches influences executives’ opinion of central bank policy more negatively than elsewhere. One possible explanation is that more communication under a more complex mandate may confuse the audience. In contrast, an array of institutional, macroeconomic, and financial variables exhibit no effect. Particularly worth mentioning is that the level of inflation, central bank independence and transparency – which in both theory and in practice are considered to be primordial for the credibility and the success of a central bank – turned out to be unimportant. Further, financial crises, the effective lower bound constraint, forward guidance, the performance of the stock market, and the volatility of the exchange rate are also irrelevant. The only significant variables (besides speeches) are economic growth and a positive output gap. As expected, both improve the opinion executives have of their central bank’s impact on the economy.

Conclusions

A good understanding of how central bank speeches affect the perception executives have of their central banks’ policies adds an important dimension to the literature on central bank communication. What policy conclusions do we draw from our analysis? As our results suggest, the challenge to central bank communication is not only in addressing the cohorts that are currently out of reach of central banks, such as the young and the less well-off; it seems to be deeper than that. Business managers are listening and, given their education, arguably coping well with the elevated level of central bank speeches. However, what they hear does not seem to increase, but rather to downgrade, the effect on the economy they attribute to their central banks. While important for informing managers about central bank policies, there may be too many speeches, especially from board members other than governors. One hypothesis in line with the evidence found in our study is that governors provide a consistent message over time, whereas other board members are more likely to convey diverging messages that confuse the receivers. This appears to be particularly critical in times of elevated uncertainty. The results echo the cacophony problem ventilated in Lustenberger and Rossi (2018) and Lustenberger and Rossi (2020) that may need fixing. This is all the more called for, if, as Blinder et al. (2017) hypothesise, central banks in the future will communicate more.

Authors note: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this column are strictly those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Korea, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) or the Swiss National Bank (SNB). The Bank of Korea, FINMA and the SNB take no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in this column.

References

Altavilla, C, R Gürkaynak, R Motto, G Ragusa (2020), “Financial market reactions to monetary policy signals”, VoxEU.org, 03 August.

Binder, C (2017), “Fed speak on main street: Central bank communication and household expectations”, Journal of Macroeconomics, 52, 238–251.

Blinder, A S (2018), “Through a crystal ball darkly: The future of monetary policy communication”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108, 567–571.

Blinder, A S, M Ehrmann, M Fratzscher, J De Haan, and D-J Jansen (2008), “What we know and what we would like to know about central bank communication”, VoxEU.org, 15 May.

Blinder, A S, M Ehrmann, J De Haan, and D-J Jansen (2017), “Necessity as the mother of invention: Monetary policy after the crisis”, Economic Policy, 32 (92), 707–755.

Duca-Radu, I, G Kenny, and A Reuter (2021), “Macroeconomic stabilisation, the lower bound, and inflation: Expectations matter”, VoxEU.org, 09 February.

Haldane, A, and M McMahon (2018), “Central bank communications and the general public”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108, 578–583.

Hwang, I D, T Lustenberger, and E Rossi, “Does communication influence executives’ opinion of central bank policy?”, Journal of International Money and Finance, forthcoming.

Lustenberger, T, and E Rossi (2018), “More frequent central bank communication worsens financial and macroeconomic forecasts”, VoxEU.org, 04 March.

Lustenberger, T, and E Rossi (2020), “Does central bank transparency and communication affect financial and macroeconomic forecasts?”, International Journal of Central Banking, 16 (2), 152–201.

Ellen, ter S, V H Larsen, L A Thorsrud (2020), “Narrative monetary policy surprises and the media: How central banks reach the general public”, VoxEU.org, 08 December.

Van der Cruijsen, C A B, D-J Jansen, and J de Haan (2015), “What the general public knows about monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 23 August.