Rising incomes in middle-income countries will lead to a surge in demand for consumer durables, leading to rapid increases in the demand for electricity and energy. Increasing access to consumer durables, electricity, and energy are important for improving living standards. At the same time, the growth of large developing nations could significantly increase global carbon dioxide emissions and this raises the spectre of extreme climate change.

Environmentalists have been deeply concerned about the trade-off between poverty alleviation and the exacerbation of the global warming externality. Back in 2008, the bestselling author Jared Diamond prioritised slowing climate change over increasing living standards in developing nations. He wrote in the New York Times in 2008:

“The average rates at which people consume resources like oil and metals, and produce wastes like plastics and greenhouse gases, are about 32 times higher in North America, Western Europe, Japan and Australia than they are in the developing world.” He continues: “Per capita consumption rates in China are still about 11 times below ours, but let’s suppose they rise to our level. Let’s also make things easy by imagining that nothing else happens to increase world consumption that is, no other country increases its consumption, all national populations (including China’s) remain unchanged and immigration ceases. China’s catching up alone would roughly double world consumption rates. Oil consumption would increase by 106 percent, for instance, and world metal consumption by 94 percent. If India as well as China were to catch up, world consumption rates would triple.” (Diamond 2008)

Can the planet accommodate development of middle-income countries? Research on the environmental Kuznets curve has posited that as nations achieve middle incomes, they begin to prioritise environmental protection (Grossman and Krueger 1995, Dasgputa et al. 2002, Hilton and Levinson 1998). This hypothesis is more likely to hold for local public bads such as air pollution and water pollution where the bulk of the damage is experienced locally. In the case of climate change, the global free rider problem still lurks (Schmalensee et al. 1998).

Three facts about the current carbon dioxide production challenge

Fact 1: A nation’s carbon emissions per-person and its average income per-person are strongly correlated

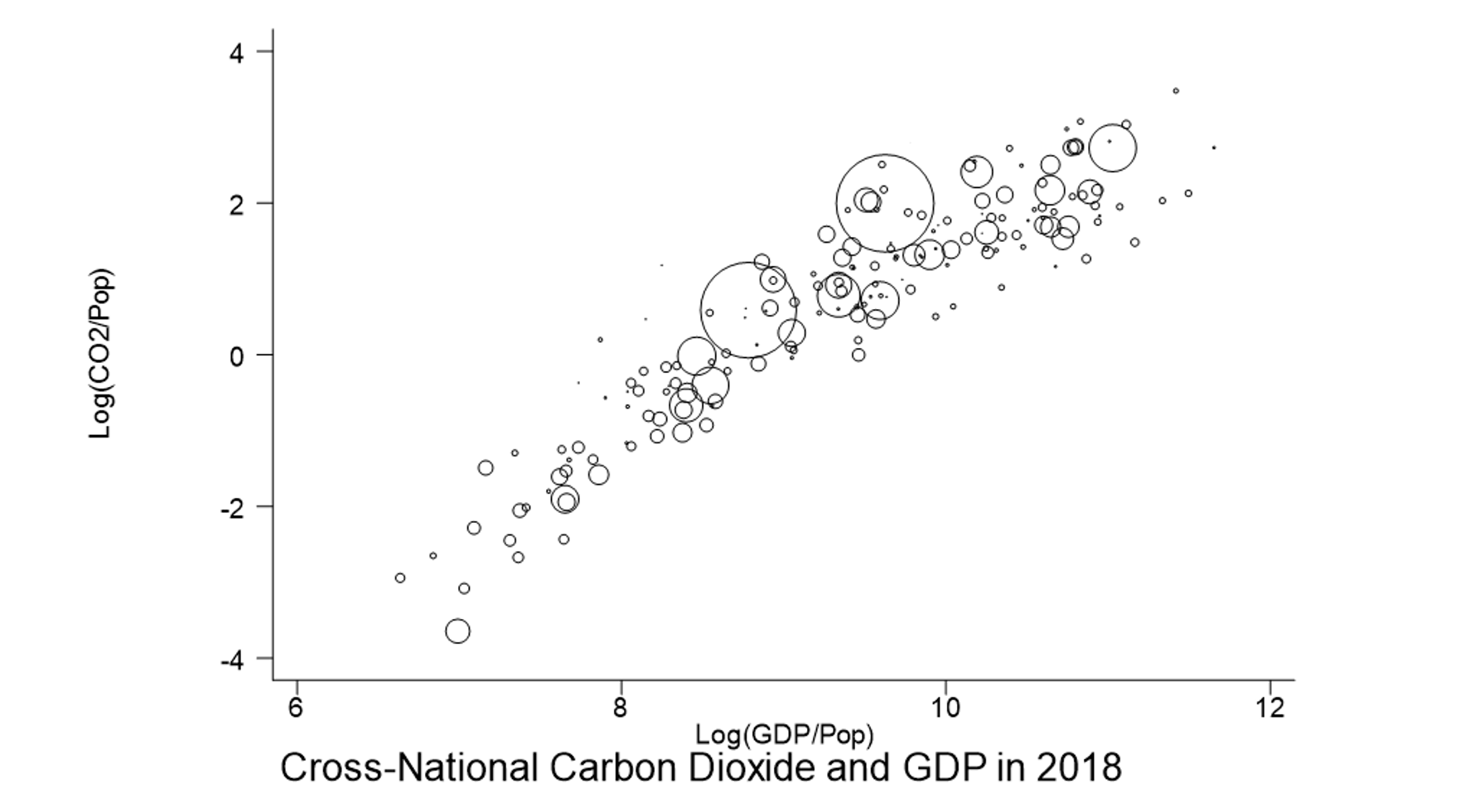

While countries around the world have made ambitious commitments through their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), developing nations sharply increase their carbon dioxide emissions as they grow richer. In Figure 1, we use data from the 2018 World Development Indicators to document a strong correlation between a nation’s carbon emissions per-person and its average income per-person. In the figure, a larger circle represents a larger country. This graph highlights that under ‘business as usual’, global greenhouse gas emissions would soar as middle-income nations, particularly large ones such as China and India, grow richer.

Figure 1 Carbon emissions per person and national GDP, 2018

Fact 2: Rising incomes in developing nations increases demand for energy-intensive durables

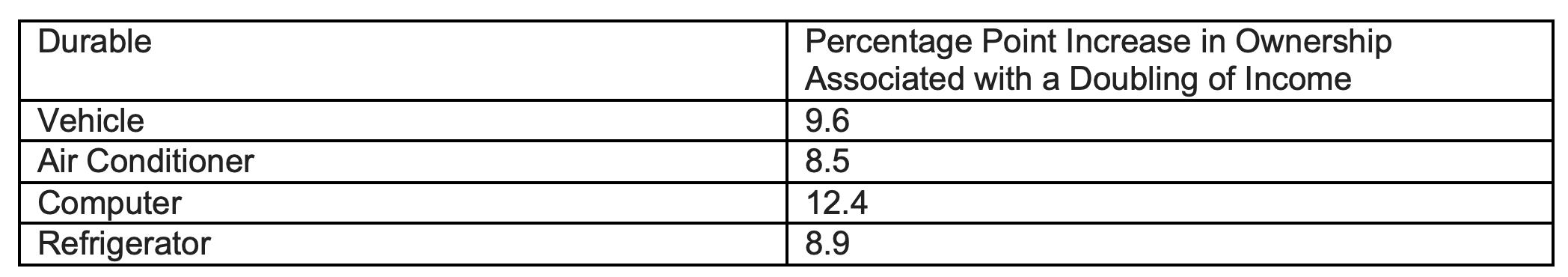

In our research, we use the World Bank’s global monitoring database to estimate how economic development is associated with ownership of key energy-intensive durables. A doubling of personal real income increases the probability of owning a vehicle by 9.6 percentage points (Kahn and Lall 2022). We find similar magnitude income effects for air conditioners and refrigerators, washing machines, cell phones, computers, and televisions.

Table 1 Durable ownership increase with incomes in developing nations

Source: Kahn and Lall (2022).

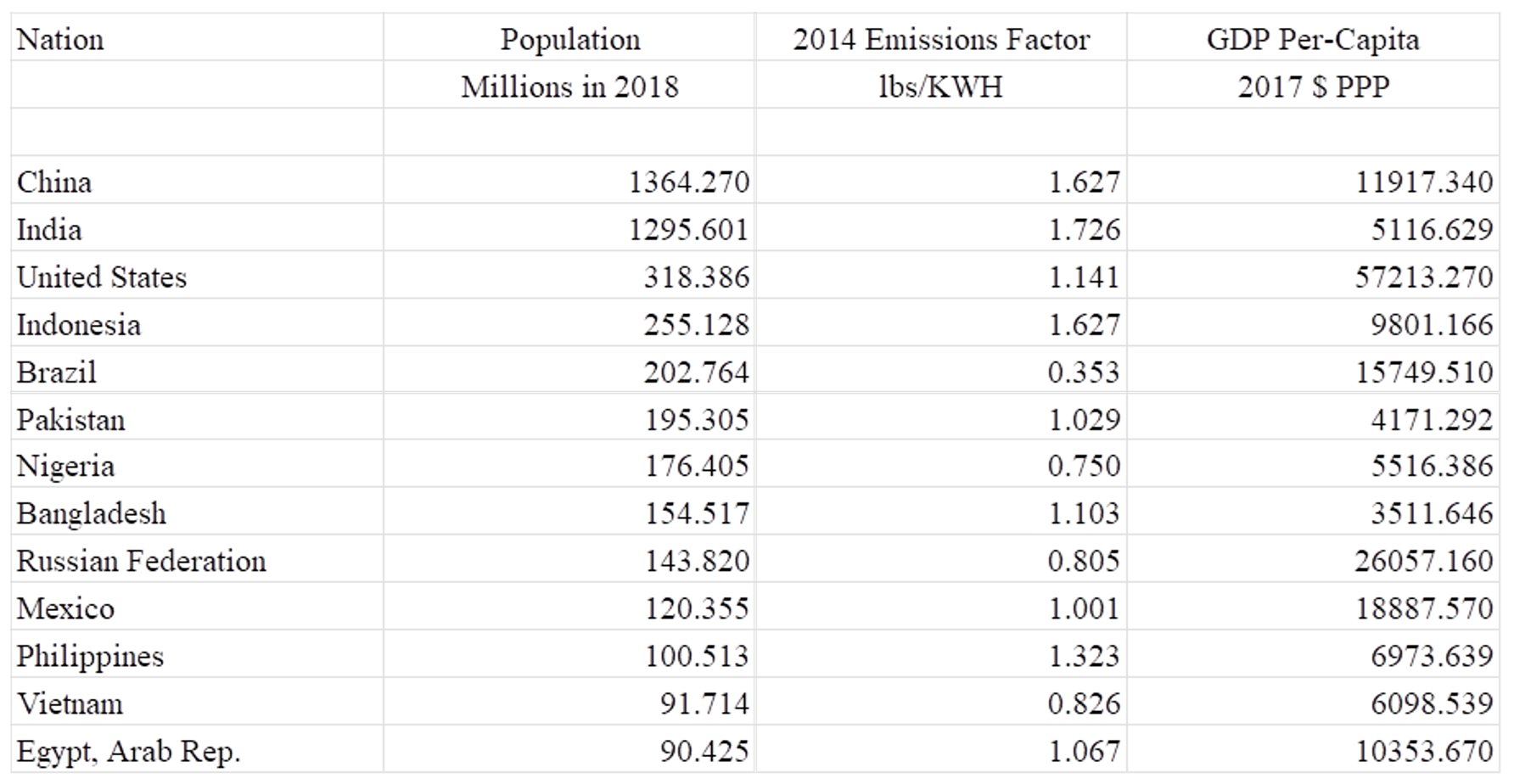

Fact 3: The grid is dirty in some of the world’s largest developing nations

The ultimate impact on global greenhouse gas emissions hinges on the nation’s electricity grid. To provide some insights about the grid in major nations, we use data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database for some of the world’s most populated nations.

Table 2 Fossil fuel reliance in electricity grid

Source: Kahn and Lall (2022)

Large middle-income nations such as China, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines feature a grid that relies on fossil fuels for generating power (Table 2). As more people in these nations grow richer and buy the durable goods according to Table 1, this exacerbates the climate change externality.

Accommodating middle-income development

If the planet is to accommodate middle-income country development, these nations will need to pivot from burning fossil fuels towards increased reliance on green power for generating electricity and transportation services. For centuries, fossil fuels have provided cheap power and this has helped to accelerate prosperity growth in developing nations.

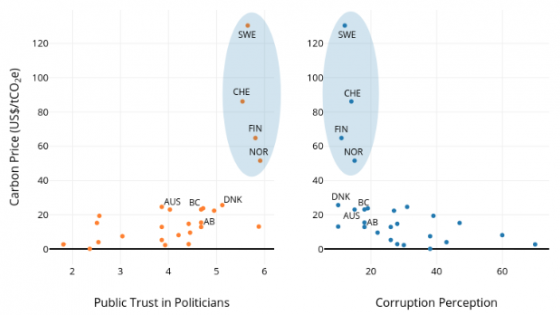

Climate economists and public finance experts have sought to dampen the reliance on fossil fuels by advocating for a carbon tax that internalises the social costs of consumption (Persaud 2021). Most economists endorse adopting a carbon tax as an incentive to economise on fossil fuel consumption. Economists continue to devise creative schemes to encourage decarbonisation and reduce political backlash (Furceri et al. 2021, Klenert and Hepburn 2018, Lemoine 2021).

A carbon tax is effective because it raises energy prices. Careful design of carbon taxes and recycling of tax revenues back to the public could alleviate losses by energy consumers. Nevertheless, governments in middle-income countries remain wary of large-scale carbon pricing schemes, given the potential for political opposition from the growing and politically influential middle class. Even in high-income France, the 2017 Yellow Vest protests highlight the populist discontent that often arises when energy prices spike. There is an emerging literature that documents that voters respond negatively to salient price increases (Douenne and Fabre 2022). Sallee (2019) emphasises the lack of precision in targeting and compensating losers as a rational choice explanation for why Pigouvian policy reforms are difficult to implement. Even in the progressive Washington state, the introduction of a carbon tax has failed to be enacted (Anderson et al. 2019).

In our ongoing research, we document evidence based on the World Values Survey that as incomes and education increase, people also become more supportive of environmental protection, and more willing to trade private consumption for a cleaner environment (Kahn and Lall 2022, Besley and Persson 2019). However, even in high-income countries, there appears to be limited support for carbon pricing schemes. In environmentally conscious Europe, we document that there are many sub-national regions featuring high carbon footprints, where elected officials are likely to oppose carbon pricing – pockets of ‘green resistance’.

While carbon-intensive development can be weakened by carbon pricing, several challenges remain. First, consider path dependence. Economic agents who have gained experience with one technology will not spontaneously switch to a new technology. Second, trade and technology transfer. Lam and Mercure (2022) show that cooperation between the US, China, and the EU is critical to create the tipping points for shifting the market durably towards the adoption of electric vehicles. China is also among the leaders in green energy, producing around 70% of the world’s solar panels, having 50% of wind turbine suppliers, and the largest production capacity for lithium-ion batteries for vehicles with 90% of global manufacturing capacity in battery storage in 2021. China would have a major role in reducing global decarbonisation costs.

In the US, the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act introduces large subsidies to accelerate the pace of endogenous green innovation. Whether these subsidies will quickly yield a new generation of affordable electric vehicles and cheaper green power that can be exported to developing nations remains an open question.

At the end of the day, the planet can accommodate middle-income development if there is progress in changing behaviours, addressing path dependence, and enabling global trade and technology transfers.

References

Anderson, S T, I Marinescu and B Shor (2019), “Can Pigou at the polls stop us melting the poles?”, NBER Working Paper No. w26146.

Besley, T and T Persson (2019), "JEEA-FBBVA lecture 2017: The dynamics of environmental politics and values", Journal of the European Economic Association 17(4): 993-1024.

Dasgupta, S, B Laplante, H Wang and D Wheeler (2002), "Confronting the environmental Kuznets curve", Journal of Economic Perspectives 16(1): 147-168.

Diamond, J (2008), "What’s your consumption factor?", New York Times, 2 January.

Douenne, T and A Fabre (2020), "Yellow vests, pessimistic beliefs, and carbon tax aversion", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Furceri, D, M Ganslmeier and J D Ostry (2021), "Design of climate change policies needs to internalise political realities", VoxEU.org, 7 September.

Grossman, G M and A B Krueger (1995), "Economic growth and the environment", The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(2): 353-377.

Hilton, F G H and A Levinson (1998), "Factoring the environmental Kuznets curve: evidence from automotive lead emissions", Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 35(2): 126-141.

Kahn, M E and S Lall (2022), “Will the Developing World’s Growing Middle Class Support Low Carbon Policies?”, NBER Working Paper No. w30238.

Klenert, D and C Hepburn (2018), “Making carbon pricing work for citizens”, VoxEU.org, 31 July.

Lam, A and J F Mercure (2022), “Evidence for a global electric vehicle tipping point”, University of Exeter working paper series number.

Lemoine, D (2021), “A Framework for Achieving Negative Emissions”, VoxEU.org, 28 July.

Persaud, A (2021), “Saving Paris: An economically efficient and equitable rescue plan”, VoxEU.org, 2 November.

Sallee, J M (2019), “Pigou creates losers: On the implausibility of achieving pareto improvements from efficiency-enhancing policies”, NBER Working Paper No. w25831.

Schmalensee, R, T M Stoker and R A Judson (1998), "World carbon dioxide emissions: 1950–2050", Review of Economics and Statistics 80(1): 15-27.