Attitudes towards immigrants have recently been central to seismic shifts in policy and politics globally, as seen in the rise of populist and nationalist parties. Various theories have posited the cause of negative attitudes and of their centrality to political movements, relying on explanations such as economic anxiety caused by labour market competition and increased fiscal burden, prejudice, and whether the issue becomes more salient for individuals through increased coverage by politicians and the media (Ceobanu and Escandell 2010, Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014).

Despite the wealth of literature on the topic, research on attitudes towards immigrants has long lacked a global context. Studies overwhelmingly focus on a few developed countries in the Western world, leading to the generalisation of truisms and best practices on communication that may actually be context-specific. In anticipation of changes both to migration flows and in the socio-political context in many countries, our recent study (Kawasaki and Ikeda 2021) aims to expand the literature through a novel use of network science to identify and compare the major determinants of attitudes towards immigrants in regions linked through migration. The results contextualise the literature on attitudes towards immigrants by taking a global context, find generalisable and unique determinants for each region, and touch on longstanding debates about the relative importance of material economic concerns and social identities.

We find that regardless of the country, prejudice is the most central determinant of attitudes towards immigrants, especially negative attitudes towards people of another race. Moreover, our findings reinforce the cross-cultural psychological literature that shows that, on average, individuals in European countries have a more values-based approach to determining attitudes, meaning that feelings towards specific issues, like towards immigrants, are derived by more stable and general attitudes, such as the importance one places on fairness or on tradition. As such, while communicating based on value may be the best way to sway debate in Europe (Du Bled et al. 2019), these strategies may have limited effect in non-European contexts where social norms have a greater influence on individual attitudes and where respondents express more ambivalent and less decisive attitudes (Ng et al. 2012).

Finally, by modelling attitudes as a network, this methodology allows us to comment on whether prejudice is determined by perceived threats to natives’ material interests and resources, known as ‘intergroup conflict theory’ (Dustmann et al. 2007, LeVine and Campbell 1972), or whether negative attitudes towards an outgroup help solidify ingroup cohesion, i.e. ‘social identity theory’ (Tajfel and Turner 1978). This study finds that while some regions saw intergroup conflict as the primary mechanism for determining prejudice, others saw a mix of both social identity theory and intergroup theory, while still others have no evidence of either theory at work. This finding suggests that greater study is needed regarding when and why these mechanisms are activated.

Data and methodology: Why use network science?

Network science is the study of complex phenomena through the analysis of the connections (edges) between entities (nodes). The advantages of this approach to the study of attitudes are as follows: first, a network of attitudes mirrors the network structure suggested by psychological and neurological literature which posits that attitudes are determined by people’s attitudes towards other relevant objects (Monroe and Read 2008); second, this approach allows for the synthesis of a large amount of data by identifying determinants of attitudes, showing the relationships amongst determinants, and finally showing the sub-community structure of determinants, i.e. which features are shaping determinants.

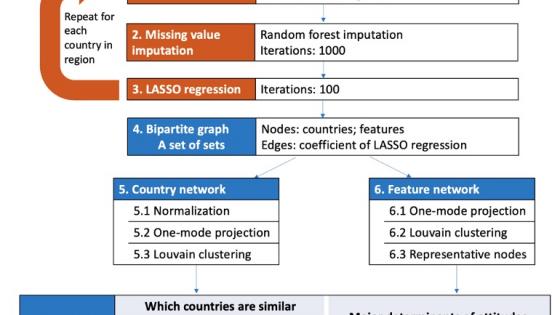

First, countries were divided into four regional networks. Using the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) bilateral matrix of migrant stock, clusters of countries with high amounts of migration among them were clustered together using a Walktrap algorithm. The four regional networks, depicted in Figure 1 are named (i) the Africa, Americas, and Asia network (AfAmAs), (ii) the Eastern Europe and Central Asia network (EE/CA), (iii) the Middle East and Southeast Asia network (ME/SEA), and (iv) the Western Europe and North Africa network (WE/NA).

Figure 1 Map of regional networks

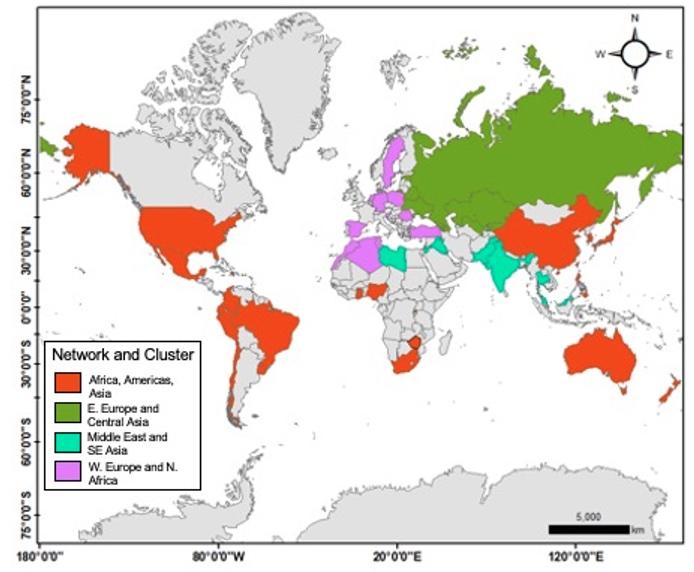

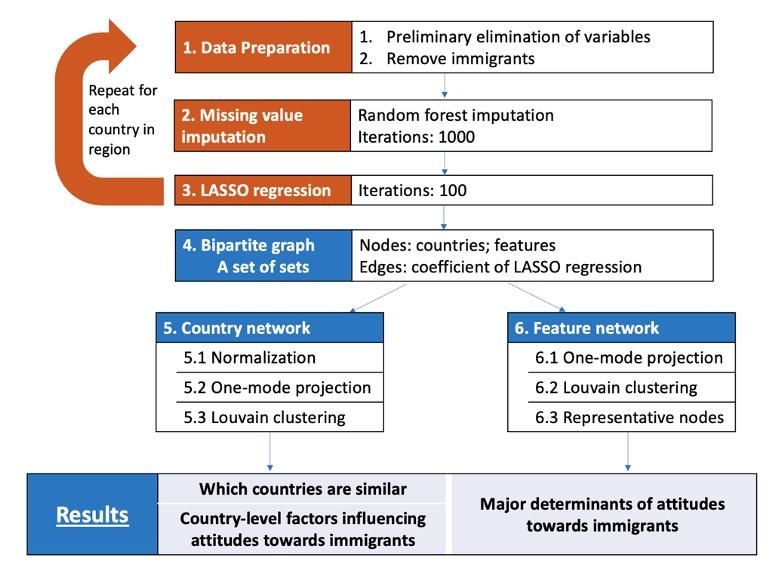

Having divided countries into regional networks, the determinants of attitudes towards immigrants were analysed in each country, according to the methodology outlined in Figure 2 Data on attitudes is taken from the sixth wave of the World Values Survey (WVS) conducted between 2010 and 2014. WVS conducts nationally representative surveys in over 50 countries using a common questionnaire regarding participants’ values, attitudes towards specific issues, and their behaviour. For this study, 56 countries were included. Attitude towards immigrants is measured by asking participants whether or not they would want to live next to immigrants or foreign workers.

Figure 2 Methodology of attitude network analysis for one regional network

A weighted adjacency matrix was then created with countries as rows and significant features as columns; elements displayed the coefficient of the LASSO regression for that feature in the country when controlling for all other significant features. From this matrix, a bipartite network was created and then projected into two one-mode networks: one representing the relative similarity/difference among countries in the same regional network (the country network), and second, the feature network, showing the correlations between features in that network.

Having created the two one-mode networks, Louvain clustering was applied in order to analyse the underlying structure of the networks. In the feature network, these clusters showed which features had higher correlations to one another than to other features in the network. These large clusters of features are called ‘determinants’, and the most centrally located node, as determined by node strength, was used to interpret its meaning, i.e. its representative node. For the country network, the Louvain clustering placed countries in groups based on the similarity of their determinants.

Results

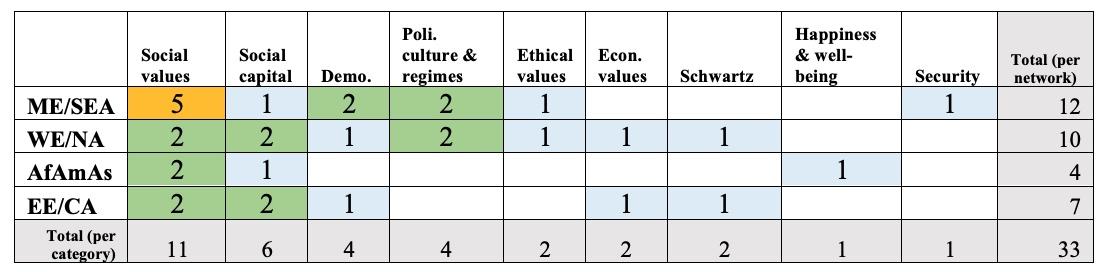

Having selected the representative nodes for each regional network, we find that some determinants remain generalisable while others appear to be distinct to their region. As can be seen in Table 1, every regional network had a high number of representative nodes in the social values category, a category that includes features related to prejudice and stigma. These features also had some of the highest node strengths, meaning they are centrally located and very influential nodes in determining attitudes. Specifically, prejudice against people of another race was the only feature to appear as a representative node in every regional network, suggesting that even in countries where migrants are the same race, racial prejudice is strongly correlated with negative attitudes towards immigrants.

Table 1 Representative nodes by category and regional network

Due to the network structure of the model, it is possible to observe the relationship between representative nodes as well as the subcommunity structure of the representative nodes – in other words, we could see how determinants influence each other and what features determine our determinants. In this way, we were able to test whether intergroup conflict theory or social identity theory was more dominant in determining prejudice by analysing the relative influence of features related to material concerns, like economic standing and concerns about economic standing, and features related to social identities, like national pride, on prejudice. From this analysis, we find that intergroup conflict theory predominates in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia network and the Western Europe and North Africa network, while both theories appear to be at work in the Middle East and Southeast Asia network. There is no evidence of either theory motivating prejudice in the Africa, Americas, and Asia networks. The inconsistency of these results suggest that these theories may be context-dependent, activated by the particularities of the country context. The exact conditions under which material resources or social identities become relevant remains an area for further study.

Finally, both the Western Europe and North Africa network and the Eastern Europe and Central Asia network contained a higher number of determinants related to values, including ethical values, economic values, and Schwartz universal human values. This finding reinforces the psychological literature which finds that cultures differ in the extent to which values determine attitudes towards specific objects, like immigrants or immigration. For policymakers and communicators on migration outside of the European context, communications that target the audience’s core values may be less effective.

Conclusion

Through this analysis, we find that generalisable determinants of attitudes towards immigrants exist, namely determinants related to prejudice towards other groups and especially negative attitudes towards people of other races. How this prejudice arises, either through perceived competition over resources or through the consolidation of an in-group identity, appears to be context-dependent and requires further research. Finally, while values-based communication may be effective in countries in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EE/CA) and Western Europe and North Africa (WE/NA) networks due to the high number of values-based determinants, these strategies may be less effective for policymakers working in countries outside of these regions. By elucidating some of the regional differences in attitudes towards immigrants, we hope that this analysis will help facilitate greater research into the country-level, causal factors of attitudes from a cross-cultural perspective.

Authors’ note: The main research on which this column is based appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Ceobanu, A M and X Escandell (2010), "Comparative analyses of public attitudes toward immigrants and immigration using multinational survey data: A review of theories and research", Annual Review of Sociology 36: 309–327, August 2010.

Du Bled, C, I Mensi and V Savazzi (2019), "What policy communication works for migration", Euromed, EU, ICMPD.

Dustmann, C, I P Preston, J Altonji, G Borjas, D Card, E Glaeser, T Hatton, H Ichimura, Z Layton-Henry, A B Satorra, C M Schmidt and F Windmeijer (2007), "Racial and Economic Factors in Attitudes to Immigration", The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 7(1): 62.

Hainmueller, J and D J Hopkins (2014), "Public attitudes toward immigration", Annual Review of Political Science 17: 225–249.

Kawasaki, R K and Y Ikeda (2021), "Network Analysis of the Determinants of Attitudes towards Immigrants across Regions", No. 21-E-097, Macro-Economy under COVID-19 Influence: Data-Intensive Analysis and the Road to Recovery.

LeVine, R A and D T Campbell (1972), Ethnocentrism: Theories of Conflict, Ethnic Attitudes, and Group Behavior, John Wiley & Sons.

Monroe, B M and S J Read (2008), "A General Connectionist Model of Attitude Structure and Change: The ACS (Attitudes as Constraint Satisfaction) Model", Psychological Review 115(3): 733–759.

Ng, A H, M Hynie and T K Macdonald (2012), "Culture Moderates the Pliability of Ambivalent Attitudes", Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 43(8): 1313–1324.

Tajfel, H and J C Turner (1978), "The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior", In H Tajfel and J C Turner (eds.), Introducing social psychology, pp. 401–466, Penguin Press.