Community engagement and responsible use of profits are issues of increasing concern to contemporary businesses. While interest in these issues is often seen as a recent phenomenon, in fact it has medieval origins.

Profit and community were reconciled in the Middle Ages in a way that we can learn from today. Medieval merchants believed that their pursuit of profit should promote the common good of the communities where they lived and worked. They re-invested profits from their business activities into philanthropic projects.

England in the late 13th century

England in the late 13th century had a dynamic economy (Britnell 1993). Manufacturing and service sectors existed alongside agriculture (Hatcher and Bailey 2001). National and international trade was conducted by enterprising merchants, aided by new institutions that lowered transaction costs. Legal advances created a lively property market and commodity trade while improvements in water management and bridge-building aided transport and infrastructure.

Towns grew dramatically, both in number and size. The period from around 1200 to around 1350 is now recognised as a period of commercial growth that was as significant as the later Industrial Revolution (Britnell and Campbell 1995).

Individualistic capitalism was not the basis for this 13th century expansion, however. In contrast, family ties and community loyalty were strong. Successful entrepreneurs used their new-found wealth to support their local community. They invested in new infrastructure to improve transport links and security and financed hospitals to care for the poor and infirm (Casson and Casson 2013, 2014).

New evidence on medieval Cambridge

Using recently discovered documents on medieval Cambridge, we have investigated how money was made through property speculation and how the profits of successful speculation were spent. Our analysis is based on over one thousand properties recorded in the so-called ‘Second Domesday’ – the Hundred Rolls of 1279 (Maitland 1898, Raban 2004).

Property markets developed in medieval England as burgage plots were laid out in new or expanding towns by local landowners (‘lords’), with the king’s permission. To acquire a plot, a burgess had to pay a perpetual rent and erect a building conforming to local plans. He could bequeath or sell his plot. Capital gains could be taken as lump sum payments or as an additional perpetual rent paid to the seller (Goddard 2004). Plots returned to the rent-recipient (e.g. the lord) if rent was not paid (Holt 2010, Keene 1985).

While the operation of commodity markets and local trade during the commercial expansion of the 13th century has been explored by economic historians, the operation of the property market has been under-researched in comparison. Our research combines statistical analysis of medieval records with detailed analysis of the backgrounds of the individuals and institutions that developed property portfolios. We identify patterns in rents, highlight strategies used to assemble property portfolios and examine how the profits of property speculation were spent (Rubin 1987).

Cambridge in the 13th century was not yet a famous university town, but rather an inland port whose merchants specialised in wholesale agricultural trade (Lee 2005). The town had origins dating from at least the 10th century, and in 1068 a castle was constructed there, followed by three religious houses in around 1092, 1133, and 1203. The River Cam provided a navigable network of waterways to Ely, Peterborough, and Huntingdon, and to ports at Wisbech and Lynn.

At the time of the Hundred Rolls, visitors from London would enter through the Trumpington Gate, with the King’s Mill to the left and the King’s Ditch on the right. Heading north, the visitor would enter the business district, with the market to the right, just behind Great St Mary’s church – one of 14 churches in the town. On the left would be buildings later demolished to make way for King’s College Chapel.

Continuing up the High Street past the Jewry would bring the visitor to the Round Church. On the left would be Hospital of St John the Evangelist, later re-founded as St John’s College (Lineham 2011). Continuing to the Great Bridge (now Magdalene Bridge) the visitor would pass St Clement’s Church, through the area where the wealthiest people resided. Passing over the bridge would provide a view up the River Cam of the great stone house (now called the School of Pythagoras) where the influential Dunning family lived.

The visitor would then ascend the Huntingdon Road, with the castle (now a mound near Shire Hall) to the right and views over the grounds of St Radegund’s Nunnery (now Jesus College) towards Barnwell Priory. A walk up the Newmarket Road would lead to hospital of St Mary Magdalene with its chapel (still standing today), and the site of Stourbridge Fair (Zutshi 1993).

Property hotspots in medieval Cambridge

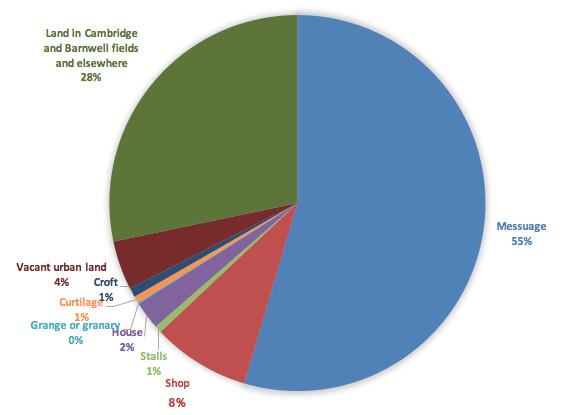

Property was a desirable asset in medieval Cambridge, much as it is today. Medieval speculators invested in a variety of properties (Figure 1). Land was popular, including fields, curtilages (the area of land around a building), vacant urban land and crofts (land adjoining dwellings, often used for agricultural purposes).

Buildings were also invested in, both residential (messuages – houses with land and often outbuildings – and houses) and commercial (shops and stalls – usually temporary structures in marketplaces). Statistical analysis of the levels of rent shows that messuages and shops were the most valuable properties.

Figure 1 Types or property

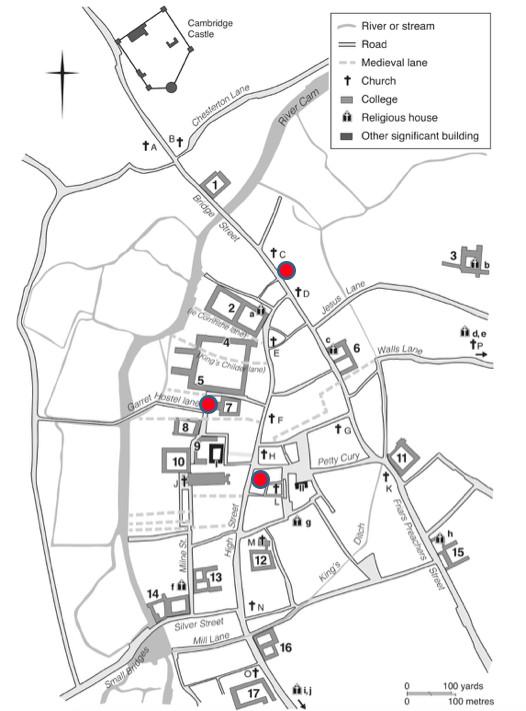

Property hotspots with high-rents can be identified in three parts of medieval Cambridge: at the road junction by the hospital; west of the market; and near the river just south of the hospital (Figure 2). Areas of notably low rents were near the castle, the area of Trumpington Street, and the suburb of Barnwell.

Figure 2 Map of medieval Cambridge showing property hotspots

Source: Adapted from Lee (2005).

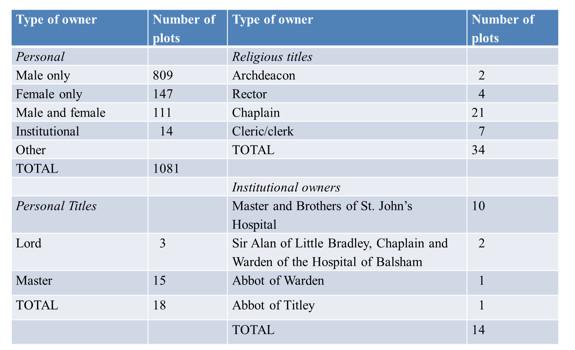

Individuals and institutions both owned property (Table 1). Family bonds often underpinned ownership. Cambridge was home to several families who had acquired property through the military service of their Norman ancestors, including the Dunning family who owned 12 plots in 1279. Property was passed down through generations. The Wombe family benefitted in 1279 from a portfolio amassed by an ancestor (Hundred Rolls, Roll 1, folio 3). The commercial revolution posed some challenges for this ‘old money’. The Dunnings mismanaged their assets and eventually left Cambridge (Gray 1932).

Table 1 Types of (rent-paying) owners

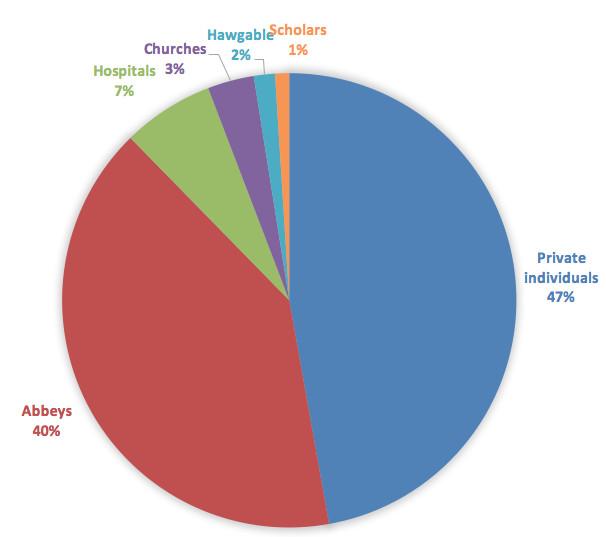

Profits from the property market were recycled back into the community through donations to religious houses, hospitals and churches. Owners allocated more rental income to charitable giving (51%) than to private individuals (Figure 3). The Barton family, for example, were important patrons of The Crutched Friars and the Nuns of St Radegund’s while the Dunnings gave land to Barnwell Priory, the Hospital of St John and St Radegund (Gray 1898; Miller 1948; Underwood 2008).

Figure 3 Types of recipients of rental income

The Black Death and its aftermath

The 14th and 15th centuries brought new challenges. The catastrophic outbreak of plague in 1348-9, known as the Black Death, probably halved the population. Major Cambridge landowners, including Barnwell Priory and Corpus Christi College, were attacked during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Properties were cleared and streets obliterated to create a new site for King’s College Chapel during the 1440s.

Yet the townspeople continued to make gifts to the monasteries, friaries, and the hospital of St John, and increasingly to new institutions, the religious guilds and the colleges. New academic colleges were founded and the university grew in size and stature, helping Cambridge to weather the economic storms of the later Middle Ages, and laying the foundations for the town’s later prosperity (Lee 2005).

Profits from property speculation benefitted individuals, family dynasties and the urban community as a whole. Compassionate capitalism involved high levels of charitable giving to hospitals, monasteries, churches, and colleges, which helped to disseminate the economic benefits of the ‘winners’ of the commercial revolution.

This self-sustaining system, however, faced challenges due to social upheaval after the Black Death, and the increased financial burdens placed on merchants and towns in order to fund warfare in France. When prosperity returned in the Tudor period a more ruthless form of capitalism took root, whose legacy remains with us today.

References

Britnell, R H (1993), The Commercialisation of English Society 1000-1500, Cambridge University Press.

Britnell, R H and B M S Campbell (1995), A Commercialising Economy: England 1096 to c. 1300, Manchester University Press.

Cambridge Hundred Rolls (1279) TNA SC5/CAMBS/TOWER/1-3.

Casson, M and C Casson (2013), The Entrepreneur in History: From Medieval Merchant to Modern Business Leader, Palgrave Macmillan.

Casson, M and C Casson (2014), “The history of entrepreneurship: Medieval origins to a modern phenomenon?”, Business History 56(8): 1223-1242.

Goddard, R (2004), Lordship and Medieval Urbanisation: Coventry, 1043-1355, Boydell Press.

Gray, J M (1932), The School of Pythagoras (Merton Hall), Cambridge Antiquarian Society.

Gray, A (1898), The Priory of St. Radegund, Deighton Bell for the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.

Hatcher, J and M Bailey (2011), Modelling the Middle Ages: The History and Theory of England’s Economic Development, Oxford University Press.

Holt, R (2010), “The urban transformation in England, 900-1100”, in C Lewis (ed.), Anglo-Norman Studies 32, Boydell and Brewer, pp. 57-78.

Keene, D (1985), Survey of Medieval Winchester, Volume 2, Part I, Clarendon Press.

Lee, J S (2005), Cambridge and its Economic Region 1450-1560, University of Hertfordshire Press.

Lineham, P (ed.) (2011), St John's College Cambridge: A History, Boydell and Brewer.

Maitland, F W (1898), Township and Borough, Cambridge University Press.

Miller, E (1948), “Baldwin Blancgernun and his family: Early benefactors of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist in Cambridge”, The Eagle 324(53): 73-79.

Raban, S (2004), A Second Domesday: The Hundred Rolls of 1279-80, Oxford University Press.

Rubin, M (1987), Charity and Community in Medieval Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Underwood, M (ed.) (2008), Cartulary of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist, Cambridge Records Society.

Zutshi, P. (ed.) (1993), Medieval Cambridge: Essays on the Pre-Reformation University (Woodbridge, Boydell and Brewer).