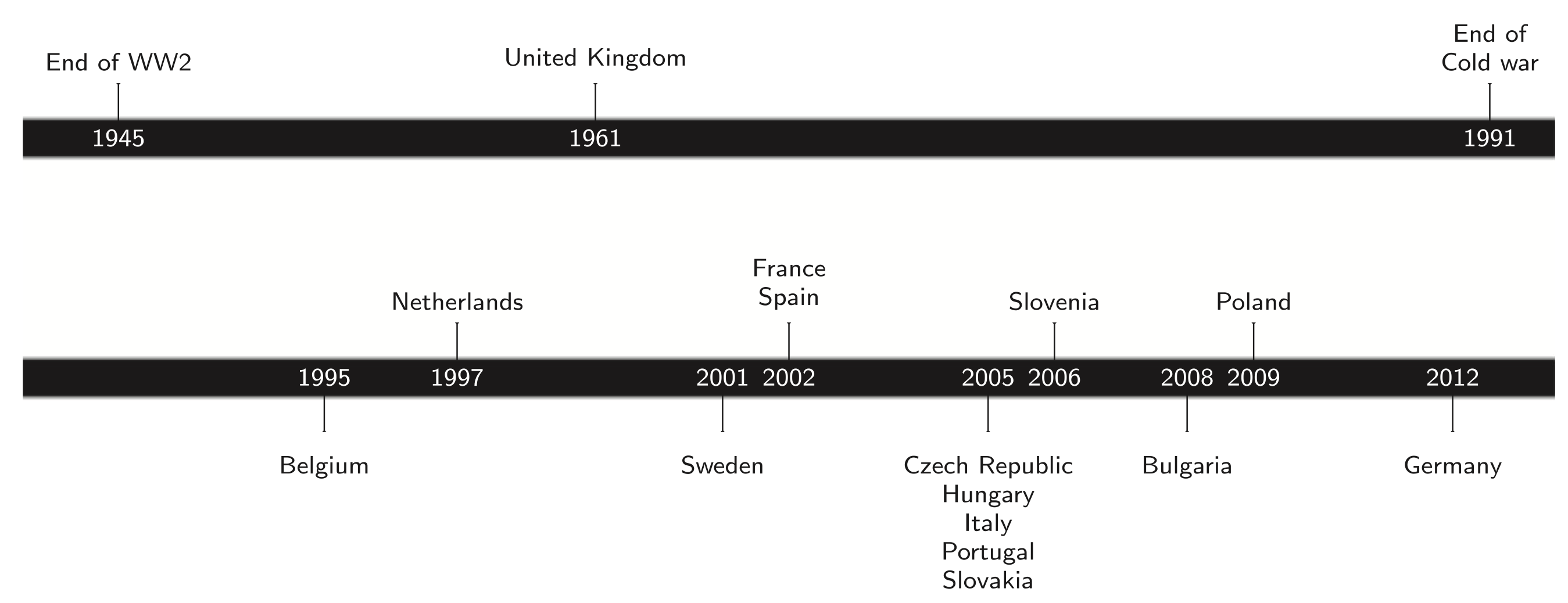

Although many expected military conscription to fall into oblivion with the end of the Cold War, the debate on its reintroduction has resurfaced cyclically in Europe (Noack 2018), despite the declining trend in military expenditure worldwide (Gupta et al. 2019). Following a major wave of reforms cancelling – or indefinitely suspending – the drafting of young citizens in the early 2000s (see Figure 1 for a timeline), only a few European countries, such as Finland and Greece, retain some form of mandatory military service to this date, mostly due to geopolitical concerns.

Figure 1 Timing of reforms across Europe

Source: Authors’ update of Toronto’s (2007) military recruitment dataset.

However, Russian expansionism, starting with the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and culminating in the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, has caused a sudden U-turn. Lithuania (BBC 2015), Sweden (Oltermann 2017), and, most recently, Latvia have re-activated their conscription programmes (Ministry of Defense, Republic of Latvia 2022), not long after first suspending them, while the Dutch government is actively considering doing so (DutchNews.nl 2022).

Even separated from their most obvious drawbacks – from the high economic cost (Poutvaara and Wagener 2007, Bove and Cavatorta 2012) and impact on the youth’s skill development (Rosolia and Cipollone 2011) to concerns of intergenerational equity (Poutvaara and Wagener 2011) – the effectiveness of conscription programmes in the realm of high-tech global contemporary warfare has been widely questioned (TheFirstNews 2022).

Border defence has been the main policy rationale behind mandatory military service. Yet, “no European people would be ready to legitimise the compulsory employment of young conscripts in missions out of national or alliance territory” (Haltiner and Tresch 2008: 172). In fact, Poland’s defence minister, Mariusz Blaszczak, withdrew a plan to reintroduce conscription, citing the country’s professional army and international alliances as sufficient for national security (TheFirstNews 2022).

Notably, the argument for reinstating mandatory military service has often diverged from national security concerns. Several European leaders appear to share a ‘romantic’ view of conscription, indebted to the state-building role this institution played in the 20th century. For instance, Emmanuel Macron launched the Service National Universel in 2017, arguing that: “At a time when the nation needs to rediscover the deep meaning of its history ... the Republic needs you to do more” (Le Monde 2022). During the 2022 electoral campaign, to-be Minister of the Interiors Matteo Salvini stated that military service would be “very useful” for Italian youth (Il Fatto Quotidiano 2022), while the president of the Italian Senate, Ignazio La Russa, re-launched his idea of a 40-day mini-draft, to teach “not only love for Italy, … but also a civic sense, the duty each of us has to help others in difficulty” (Agenzia Italia 2022).

Recently, the defence minister in Olaf Scholz’s centre-left government, Boris Pistorius, defined Germany’s decision to phase out conscription in 2011 as “a mistake” (Oltermann 2023). Interestingly, Pistorius’s argument did not rest on the threat posed by Russia’s aggressive foreign policy but rather pointed at the role of conscription in retaining “a connection to civic society at large” among the youth. Our research (Bove et al. 2022) suggests that reintroducing mandatory military service is actually unlikely to bridge the widening gap between the citizen and the state.

Although the ‘equalising’ role of conscription in society has been recently questioned (Hjalmarsson and Lindquist 2016), numerous scholars have long argued that the historical objective of the policy is to serve as a ‘school of nation’. During their months as conscripts, young peers from different regional, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds interact in isolation from ‘civil’ society. Exposure to national symbols and core military values during their impressionable years is expected to boost young people’s civic obligations towards the state, forging patriotism and loyalty, and instilling a sense of shared national mission. Indeed, research has found that military conscription contributed to the formation of a shared national identity (Cáceres-Delpiano et al. 2021), boosting loyalty to the polity (Leander 2004), and instilling patriotism (Ertola Navajas et al. 2022).

Yet, it remains unclear whether the transfer of patriotic values translates into support for the political institutions the military is instructed to serve, as many pundits claim. This link is far from obvious, as testified by the narrative of populist forces: celebrating their nation’s splendour while simultaneously bashing the state’s checks and balances. The highly structured and isolated environment of military organisations can shape civic identity along military norms, leading to a strong identification with the armed forces that may clash with loyalty towards democratic institutions.

For one, the military’s natural desire to expand its organisational scope of action, overruling the monitoring of elected bodies, may lead the young, malleable draftee to see civilian oversight and democratic institutions as a constraint to the agile, vertical decision-making style they have become accustomed to within the military. Our analysis demonstrates how this ‘civil-military gap’ results from the formation of a homogeneous community with uniform values.

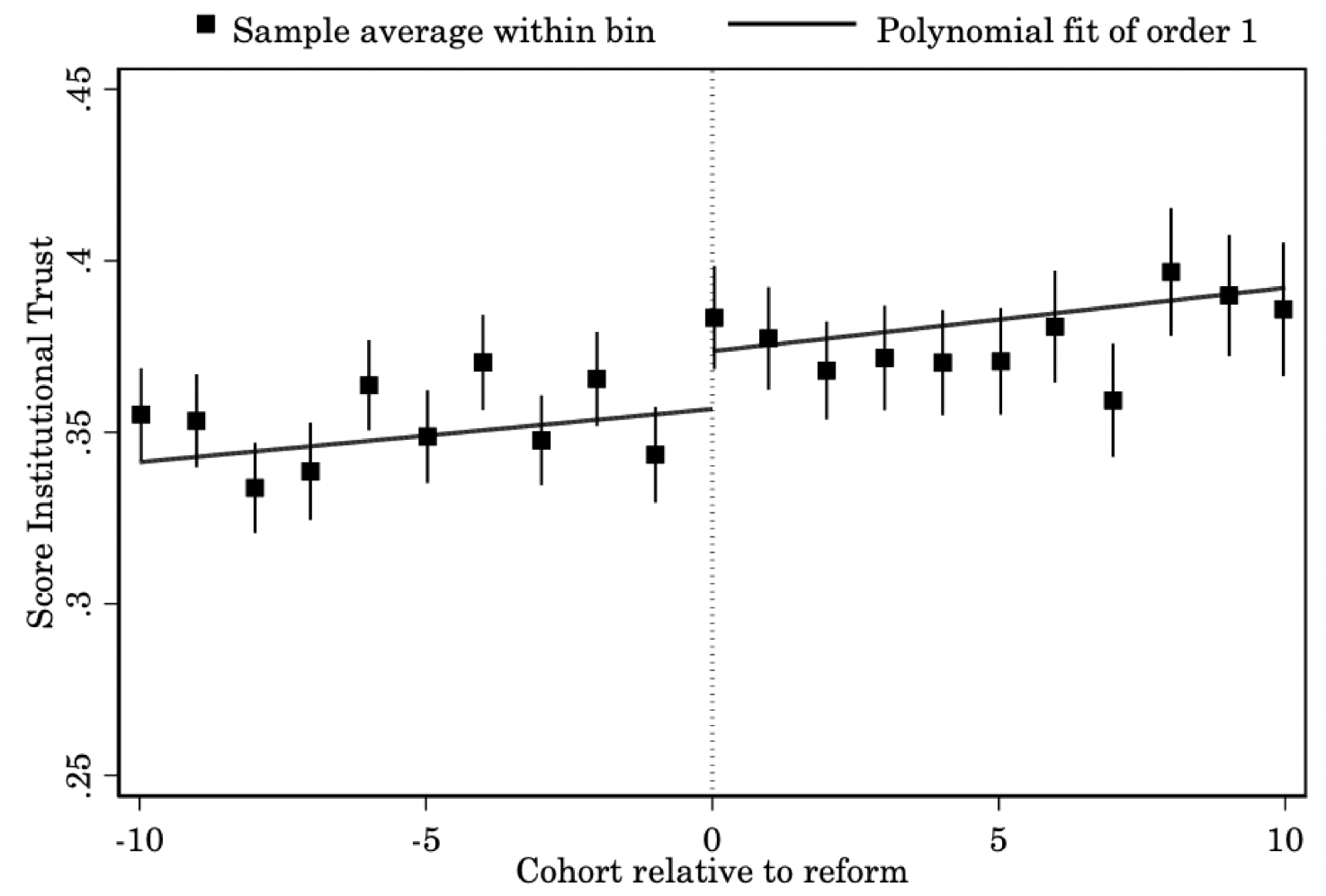

Using data from the European Social Survey, we study the political attitudes of citizens from 15 European countries which have suspended military conscription in the last century. We compare men from contiguous generations, hence exposed to the same political context throughout their life, and that those born not quite late enough to be affected by the reform display less trust in democratic institutions than those just exempted from the draft (Figure 2, Panel A).

Figure 2 End of conscription and institutional trust

(a) Men

(b) Women

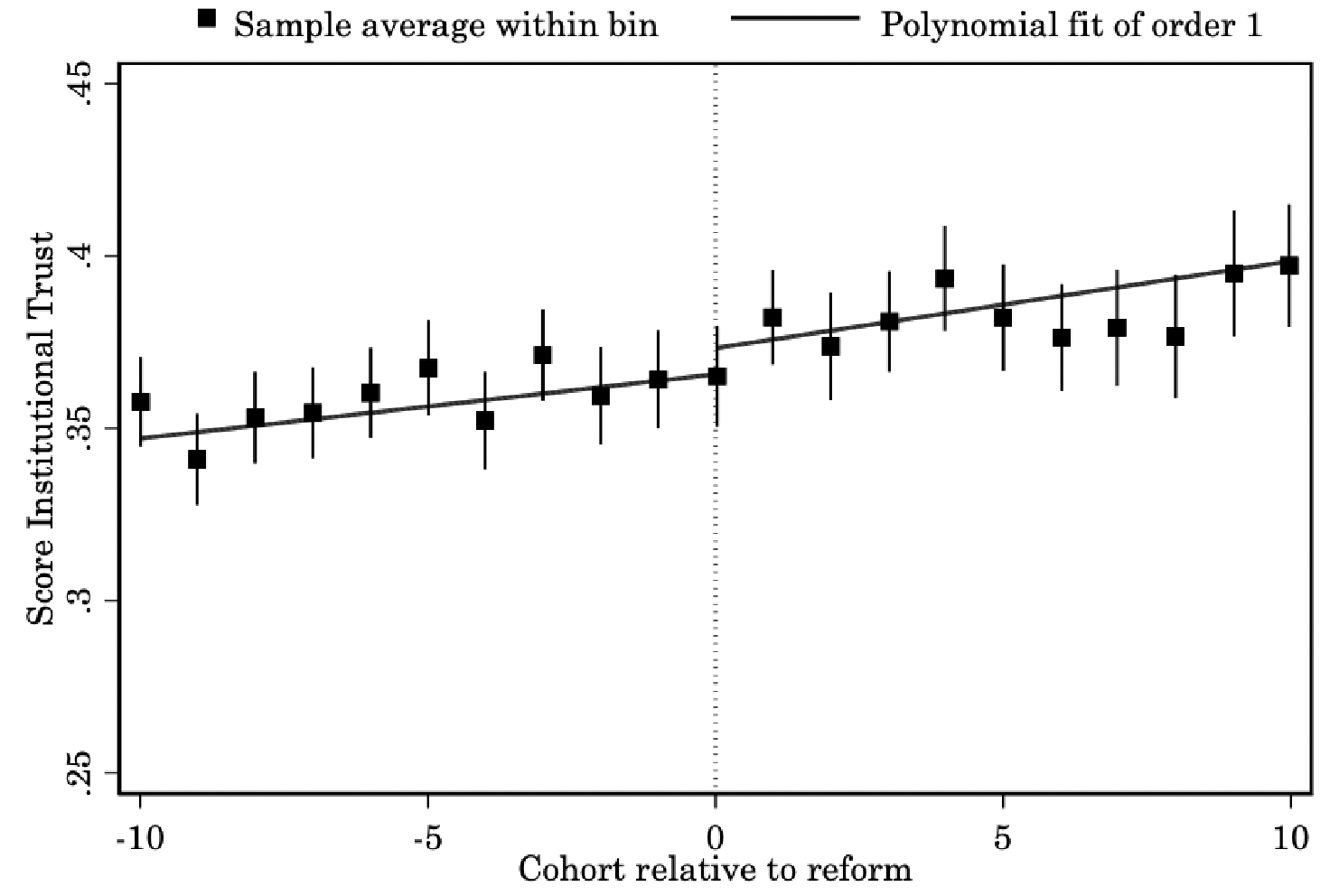

The effect is not the by-product of a generational shift in attitudes towards the state among the European public opinion: women from comparable cohorts, who were not required to serve, do not show such changes in institutional trust (Figure 2, Panel B). Furthermore, the effect ascribed to the military service is not driven by changes in the conscripts’ career and educational development, which could have enhanced their individual socioeconomic outcomes and, possibly, attitudes towards the country’s institutions (Gelepithis and Giani 2022).

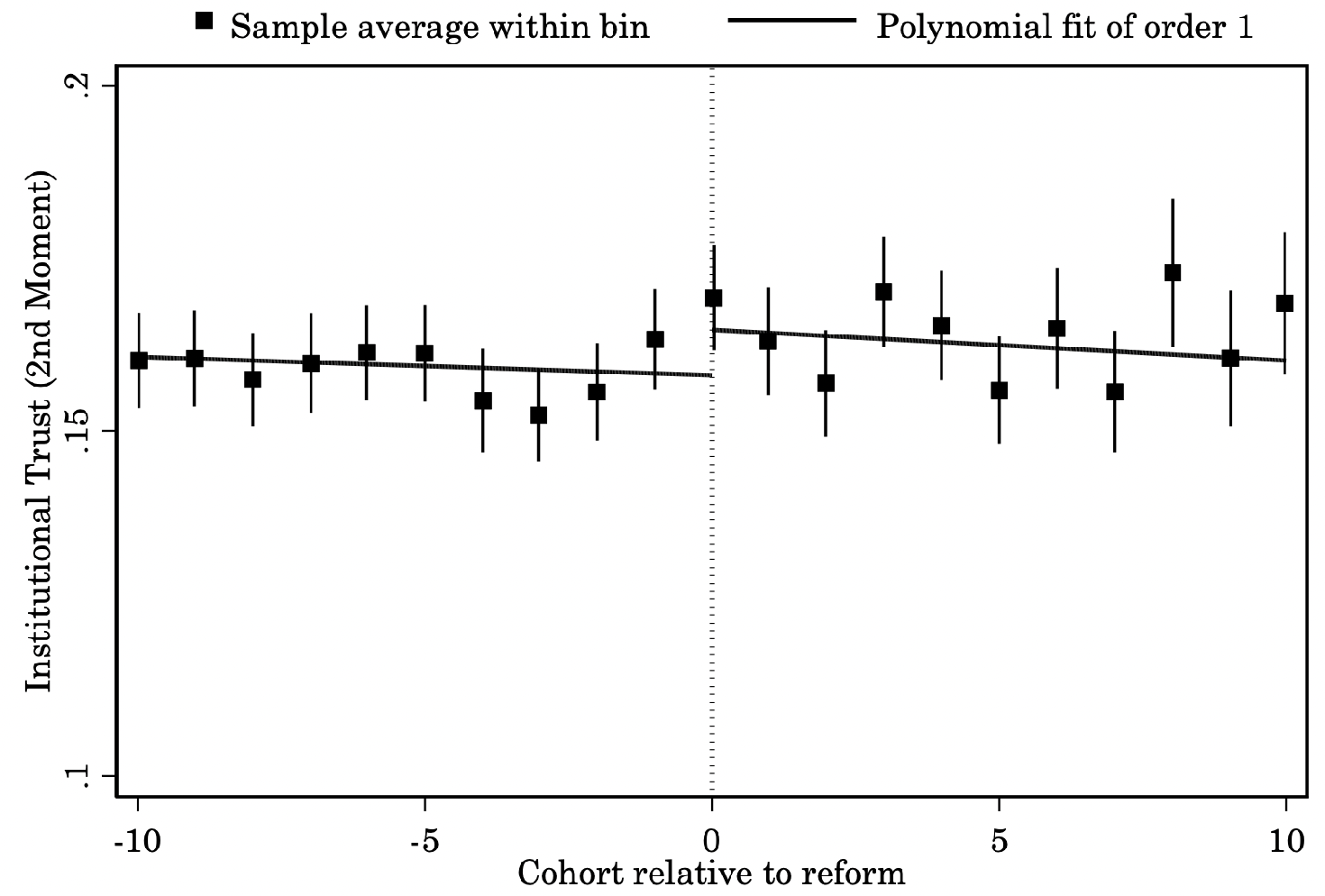

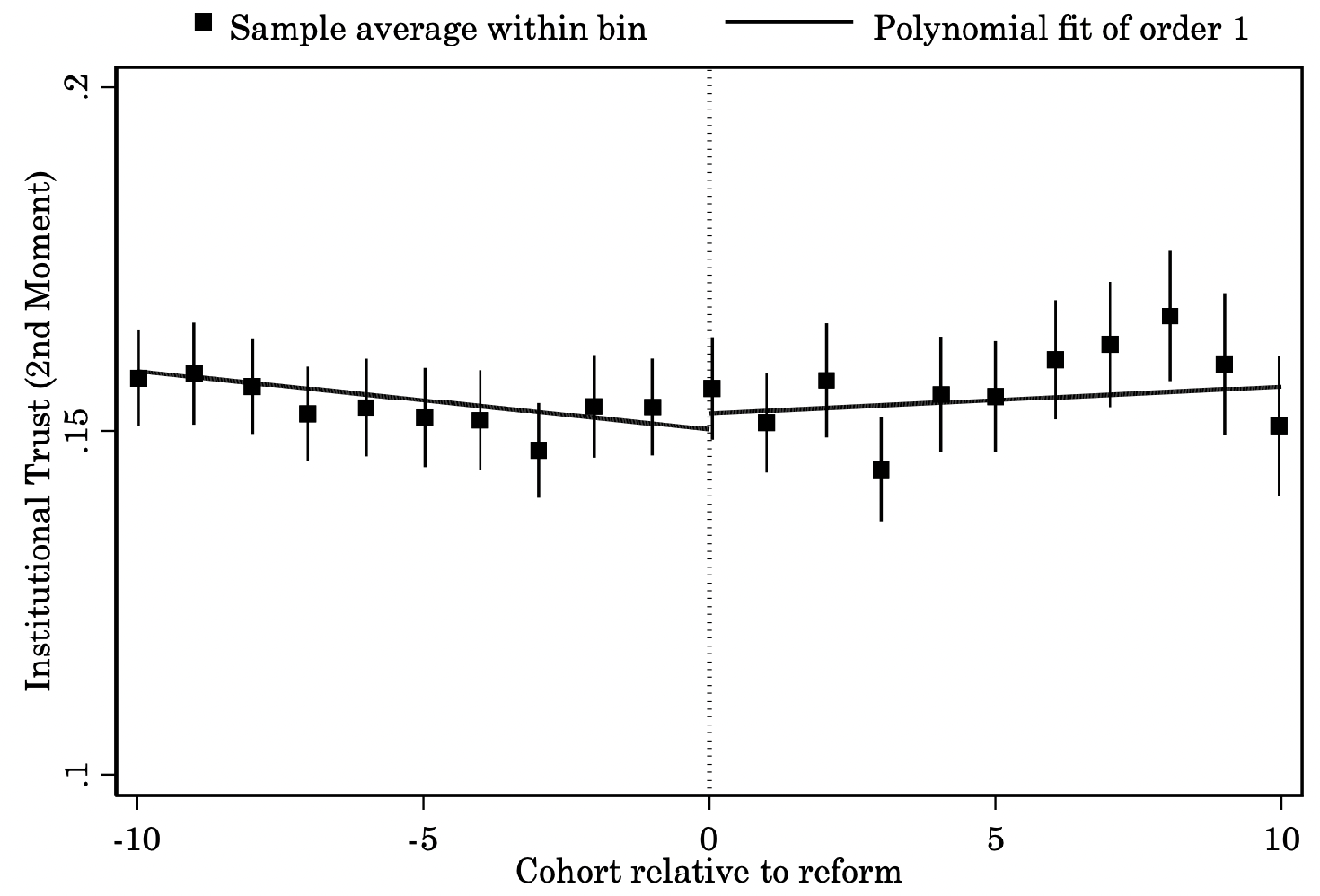

This negative effect on trust is observed for entities more prone to ideological capture, such as parties or politicians, but also for the parliament and the judicial system. On the contrary, we do not see any impact on the evaluation of the executive in charge at the time of the interview, suggesting that the effect we estimate is not contextual but rather associated with a more stable shift in attitudes. Our analysis also reveals that draftees form a community characterised by negative and more homogeneous attitudes towards their country’s institutions, consistent with the notion of a ‘civil-military gap’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Polarisation of institutional trust

(a) Men

(b) Women

That draftees display lower trust later in life holds in Western and Eastern European countries alike, although the effect is stronger in the latter. Two possible explanations for this pattern come to mind. First, when transitioning to an all-volunteer force, former members of the Warsaw Pact lagged behind Western democracies in terms of several democracy indexes, including the pervasiveness of military corruption. Second, the suspension of conscription in Eastern countries was only a piece in the complex jigsaw puzzle of post-USSR democratisation, which involved a significant reorganisation of defence policies and civil-military relations (e.g. Latawski 2013), making it difficult to isolate the effect of the suspension of conscription.

Mounting geopolitical concerns have undoubtedly played a major role in the reactivation of drafting programmes in several countries. Still, the political debate on such policy has often built upon the objective of (re-)building trust towards institutions upon the pillars of military culture: hierarchy and patriotism. Yet, as far as political attitudes are concerned, conscription appears to weaken the relationship between the citizen and the state. In the military ‘school of nation’, exposure to hierarchical chains of command and homogeneous worldviews are likely to matter more than camaraderie in shaping one’s views of how democratic institutions should operate.

Our results suggest that the military experience may lead young men to prioritise the military over (mistrusted) democratic institutions, highlighting a risk for the development of civic values. New – and perhaps more complex – approaches should be pursued by contemporary policymakers to promote civic duties and strengthen the youth’s relationship with their country’s institutions. This is particularly important in today’s atomised societies, where such values may be less consolidated than ever before.

References

Agenzia Italia (2022), “La Russa propone una ‘mini naja volontaria’ di 40 giorni”, Agenzia Italia, 11 December.

BBC (2015), “Lithuania to reintroduce conscription over security concerns”, BBC News, 24 February.

Bove, V, and E Cavatorta (2012), “From conscription to volunteers: budget shares in NATO defence spending”, Defence and Peace Economics 23(3): 273–88.

Bove, V, R Di Leo, and M Giani (2022), “Military culture and institutional trust: Evidence from conscription reforms in Europe”, American Journal of Political Science.

Cáceres-Delpiano, J, A I De Moragas, G Facchini, and I González (2021), “Intergroup contact and nation building: Evidence from military service in Spain”, Journal of Public Economics 201: 104477.

DutchNews.nl (2022), “Defense ministry is looking into Scandinavian style conscription”, DutchNews.nl, 8 April.

Ertola Navajas, G, P A López Villalba, M A Rossi, and A Vazquez (2022), “The long-term effect of military conscription on personality and beliefs”, Review of Economics and Statistics 104(1): 133–41.

Gelepithis, M, and M Giani (2022), “Inclusion without solidarity: Education, economic security, and attitudes toward redistribution”, Political Studies 70(1): 45–61.

Gupta, S, S Khamidova, and B Clements (2019), “Converging military spending and its fiscal consequences”, VoxEU.org, 6 October.

Haltiner, K W, and T S Tresch (2008), “European civil–military relations in transition: The decline of conscription”, in Armed Forces and Conflict Resolution: Sociological Perspectives, Emerald Group Publishing.

Hjalmarsson, R, and M Lindquist (2016), “The causal effect of military conscription on crime and the labor market”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP11110.

Il Fatto Quotidiano (2022), “Salvini insiste sul ritorno del servizio militare: ‘È molto utile’. Unarma: ‘Momento delicato, arruolare giovani impreparati è un rischio’”, Il Fatto Quotidiano, 26 August.

Latawski, P (2013), “The transformation of postcommunist civil-military relations in Poland”, in Civil-Military Relations in Postcommunist Europe, Routledge.

Le Monde (2022), “Emmanuel Macron exhorte les armées à développer le Service national universel”, Le Monde, 14 July.

Leander, A (2004), “Drafting community: Understanding the fate of conscription”, Armed Forces and Society 30(4): 571–99.

Ministry of Defense, Republic of Latvia (2022), “Ministry of Defence begins to work on gradual introduction of State Defence Service”, 7 November.

Noack, R (2018), “The military draft is making a comeback in Europe”, Washington Post, 19 October.

Oltermann, P (2017), “Sweden to reintroduce conscription amid rising Baltic tensions”, Guardian, 2 March.

Oltermann, P (2023), “German politicians and military chiefs suggest return of conscription”, Guardian, 9 February.

Poutvaara, P, and A Wagener (2007), “Conscription: economic costs and political allure”, Economics of Peace and Security Journal 2(1).

Poutvaara, P and A Wagener (2011), The political economy of conscription. In The handbook on the political economy of war, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rosolia, A, and P Cipollone (2011), “Schooling and youth mortality: Learning from a mass military exemption”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP8431.

TheFirstNews (2022), “Poland not to re-introduce conscription, says MoD”, 23 August.

Toronto, N (2007), “Military recruitment data set”, Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Foreign.