Editor's note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the Vox eBook, The Long Economic and Political Shadow of History, Volume 2, available to download here.

When economists debate the long-lasting legacies of colonisation, the discussion usually revolves around the establishment of those ‘extractive’ colonial institutions that outlasted independence (e.g. Acemoglu et al. 2001), the underinvestment in infrastructure (e.g. Jedwab and Moradi 2016), the identity of colonial power (e.g. La Porta et al. 2008) and the coloniser’s influence on early human capital (Easterly and Levine 2016).1 Following the influential work of Nunn (2008), recent works have explored the deleterious long-lasting consequences of Africa’s slave trades (see Nunn 2016, for an overview). Yet, between the slave-trade period (1400-1800) and the arrival of the colonisers at the end of the 19th century, the Scramble for Africa stands out as a watershed event in the continent’s history. The partitioning of Africa by Europeans starts, roughly, in the 1860s and is completed by the early 1900s. The colonial powers signed hundreds of treaties, which involved drawing on maps the boundaries of colonies, protectorates, and ‘free-trade’ areas of a largely unexplored and mysterious continent (see Wesseling 1996 for a thorough discussion).2 In this context it is perhaps not surprising that many influential scholars of the African historiography (e.g. Asiwaju 1985, Wesseling 1996, Herbst 2000) and a plethora of case studies suggest that the most consequential aspect of European involvement in Africa was not colonisation per se, but the erratic border designation that took place in European capitals in the late 19th century.

At the time of the Scramble for Africa, Europeans had limited knowledge of the local political, economic and geographic conditions. Furthermore, they were in a rush to partition the continent, in order to finance industrialisation in Europe and the Americas. As such, they did not even wait for reports from the great explorers who were then mapping the continent.3 Whilst conspiracy theories abound, A. I. Asiwaju (1985) summarises the consensus view of the African historiography: “the study of European archives supports the accidental rather than a conspiratorial theory of the marking of African boundaries.”4 A key objective shared by the colonisers, with memories of the Napoleonic Wars fresh in their minds, was to prevent conflict amongst themselves over African territory. As British Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, famously put it:

“We have engaged in drawing lines upon maps where no white man’s feet have ever trod. We have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, only hindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where the mountains and rivers and lakes were.”

While, upon African independence, policymakers, scholars, and development experts argued for the need to redraw borders, departing colonisers did not want to open this perceived ‘Pandora’s box’; and many of the leaders of African independence harboured a firm belief that nation-building policies, industrialisation, and a notion of Pan-Africanism would eventually attenuate ethnic differences and animosity.5

Jeffrey Herbst (2000) summarises: “for the first time in Africa’s history [at independence], territorial boundaries acquired salience...The boundaries were, in many ways, the most consequential part of the colonial state.”

Recent research shows that the Scramble for Africa has contributed to economic, social and political underdevelopment, via several channels. First, by partitioning numerous ethnic groups into more than one contemporary country,6 it has spurred ethnic-tainted civil conflict and also promoted repression and ethnic-based discrimination (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2016). Second, the Scramble for Africa crucially shaped the ethnic composition of the newly independent states (leading to ethnic polarisation, fractionalisation, and inequality), which, in turn, has influenced institutional and economic development, public goods provision, and conflict. Third, the Scramble resulted in Africa having a large share of landlocked countries, a situation which crucially inhibits their access to global markets (Collier 2007). Fourth, as a consequence of the artificial colony/protectorate design, many African countries are either tiny or absurdly large, while others have peculiar shapes (Herbst 2000); these features limit the reach of a state beyond its capital, and thus weaken the enforcement of laws, which, in turn, impedes development (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2014).

In this column, we summarise the key findings of recent empirical works that use high- resolution geo-referenced data and econometric methods to estimate the long-lasting impact of the various aspects of the Scramble for Africa.

Ethnic partitioning and civil conflict

Identifying partitioned ethnicities

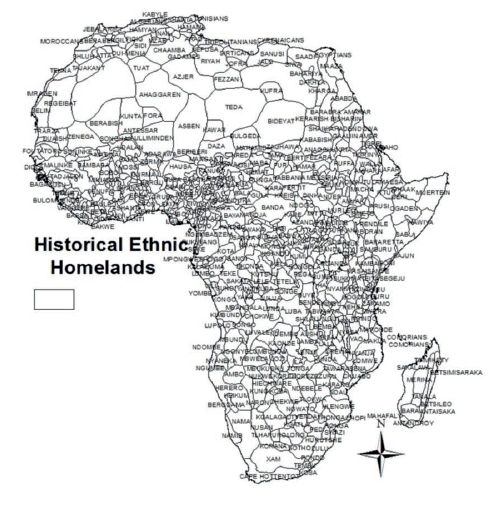

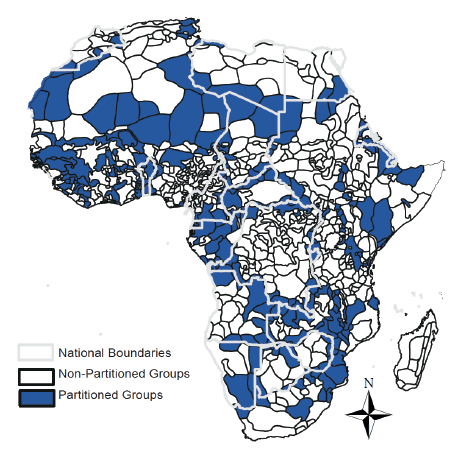

Quantifying the impact of the Scramble for Africa requires the identification of partitioned groups in a systematic manner. In Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016), we project contemporary country borders onto George Peter Murdock’s Ethnolinguistic Map (1959), which depicts the spatial distribution of African ethnicities at the time of colonisation, during the late 19th and early 20th century (Figure 1a).

We classify as partitioned those ethnicities with at least 10% of their ancestral landmass belonging to more than one country. As a result, out of the 825 mapped groups, 229 are classified as partitioned (Figure 1b). There is clearly noise in Murdock’s map and the map does not allow for ethnic overlapping, something that obviously was the case; moreover, Africans evidently could, and did, move. Yet, although not perfect, this simple and transparent procedure identifies most major partitioned ethnic groups, based on both qualitative evidence (Asiwaju 1985) and casual empiricism. For example, the Maasai have been split between Kenya and Tanzania, the Anyi between Ghana and the Ivory Coast, and the Chewa between Mozambique, Malawi, and Zimbabwe.

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

A primer on border artificiality

The African historiography provides ample case-study evidence on the artificial nature of colonial borders; but in some cases Europeans did try to accommodate local conditions. Hence, we examine whether partitioned and non-split homelands differ with respect to various geographic, ecological, political, and other historical features, since this may shed light on whether these traits influenced the colonisers’ map making. With the exception of the land mass of the historical ethnic homeland and (weakly) the presence of lakes, there are no major differences in the regions of split and non-split groups across dozens of geographic-ecological aspects (e.g. soil quality, elevation, prevalence of malaria).

There are also no systematic differences across several pre-colonial, ethnic-specific, institutional, cultural, and economic features, such as the size of settlements, the type of subsistence economy, and proxies of pre-colonial conflict.

Ethnic partitioning and conflict

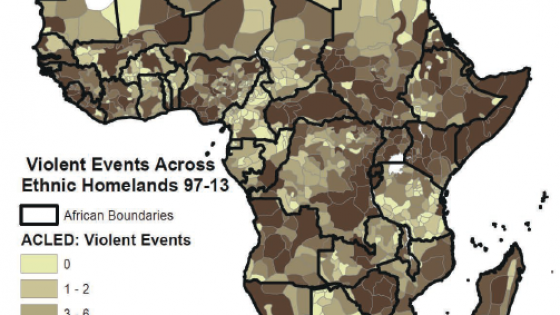

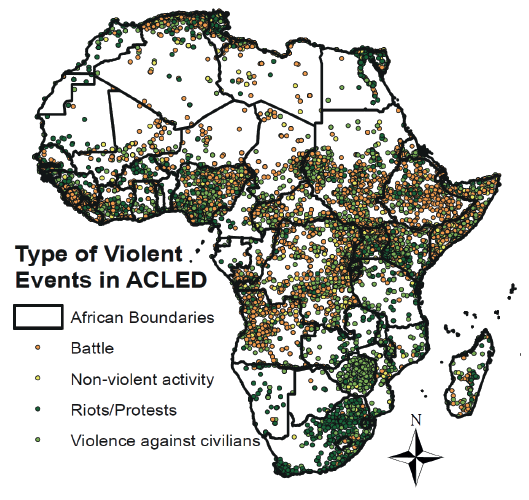

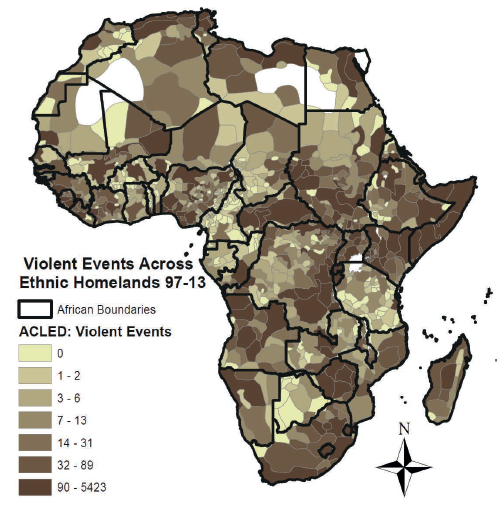

We then quantify the impact of ethnic partitioning on civil conflict, using data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) This dataset reports georeferenced information on battles between government forces, rebels and militias; violence against civilians; foreign interventions; conflict between non-state actors; and riots/protests.

Figure 2a portrays the spatial distribution of violence in Africa over the period 1997-2013 (coverage increases considerably after 2010, but this does not much affect the results). The map plots 64,650 high-precision georeferenced conflicts. There is noteworthy heterogeneity. There are numerous events in Central Africa, mostly in Eastern Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda. In Western Africa, conflict and political violence are concentrated in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. In Eastern Africa, violence is pervasive in Somalia. There is also considerable variation within countries. For example, while conflict in Tanzania is low, there are several violent events along the border with Kenya and Rwanda. Most of the conflict in Angola is close to the northern border with DRC and in the oil-rich Cabinda enclave.

Both early works, examining the long-run effects of historical factors on economic development, and the voluminous academic literature on the correlates of civil conflict, have relied on cross-country comparisons (Blattman and Miguel 2010); yet this approach, while naturally the first step, is prone to various conceptual and econometric shortcomings, as countries differ along many dimensions, the features shaping warfare and underdevelopment are correlated and there are not that many observations. We thus conduct the analysis at the historic-ethnic-homeland level, comparing conflict intensity across ethnic regions in the same country. By doing so, we effectively account for national politics, colonial and post-independence country-wide institutions, and other country features that may affect conflict. Moreover, since we examine ethnic regions in the same country, unobserved heterogeneity is less of a concern. Figure 2b portrays the spatial distribution of all conflict events at the country-ethnic homeland level.

Figure 2a

Figure 2b

The econometric analysis reveals that civil conflict is significantly higher in the ethnic regions of partitioned, as compared to non-split, groups. This applies to conflict intensity (number of conflict events), the duration (in years) of conflict, fatalities, and the likelihood of conflict. The significant association between ethnic partitioning and conflict is present, when we restrict estimation to ethnic homelands close to the national borders, so as to account for any border effects (which nonetheless may be driven by partitioning). The estimates suggest that conflict intensity is approximately 40% higher and conflict lasts on average 55% longer in the homelands of partitioned ethnicities. Moreover, the likelihood of conflict is approximately 8% higher in the homelands of split ethnicities.

The econometric analysis reveals sizable spillovers – conflict intensity is approximately 30% higher and the likelihood of conflict increases by 7% in the homelands of groups where 50% of surrounding groups are split (as compared to groups whose neighbours are not partitioned).

We then examine what type of conflict is more likely to occur in partitioned ethnic homelands. First, we document that military interventions from adjacent countries are more common in the homelands of partitioned groups than in nearby border areas where non-split groups reside. Second, we find that partitioning is a key factor for conflict between government troops and rebel groups “whose goal is to counter an established national governing regime by violent acts” and, to a lesser extent, for one-sided violence against civilians. These patterns are corroborated using a different georeferenced conflict database (the Uppsala Conflict Data Program Georeferenced Event Dataset) that records only deadly events associated with major civil wars. There is no link between ethnic partitioning and riots/protests, which are predominantly an urban phenomenon; and there is no association between partitioning and conflict between non-state actors.

Ethnic partitioning and political violence

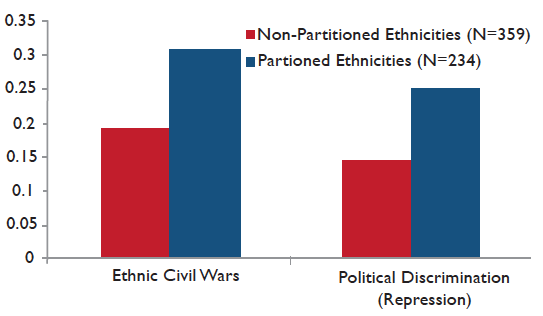

We then dig deeper regarding the partitioning-repression-civil war nexus, using the Ethnic Power Relations (EPR) dataset (Wimmer et al. 2009), which offers an assessment of ethnic-specific political participation and discrimination since independence. This dataset also gives a classification of ethnic-based civil wars.

The within-country analysis reveals three key findings. First, partitioned ethnicities are significantly more likely (an 11%-14% higher likelihood) to engage in civil wars that have an explicit ethnic dimension. Out of the 234 split groups, 72 (31%) have participated in an ethnic civil war – with the corresponding statistic for non-split groups being 69 out of the 359 (19%) (Figure 3). Second, the likelihood that split ethnicities are subject to political discrimination from the national government is approximately seven percentage points higher when compared to non-split groups. Of split groups, 25% (58 of the 234) have been subject to discrimination by the government, while the respective likelihood for non-split groups is ten percentage points lower (Figure 3).

Third, when we examine the impact of ethnic partitioning, jointly on one-sided violence (repression) and two-sided violence (civil war), we find that, in the weakly institutionalised African countries, ethnic partitioning leads much more often to major two-sided conflict, than to discrimination.

Figure 3

We complement the group-based analysis with results linking individual-level access to public goods and education to the location and the ethnicity of roughly 85,000 households across 20 African countries (using the Demographic and Health Surveys, DHS). The econometric analysis reveals that individuals who identify with partitioned groups have fewer household assets, poorer access to utilities, and worse educational outcomes, as compared to individuals from non-split groups in the same country (and even residing in the same town/village). This pattern is not due to a generalised decline in the standards of living for all households residing in split homelands; rather, it is driven by the poorer economic performance of members of split ethnicities, irrespective of their residence.

The evidence from the EPR and DHS shows that the consequences of ethnic partitioning are not circumscribed by the contours of ancestral ethnic homelands, but have significant repercussions for the members of partitioned groups, irrespective of their whereabouts.

Country level characteristics shaped by the Scramble and contemporary development

Besides ethnic partitioning, scholars have emphasised the negative impact of various country-wide aspects stemming from the Scramble for Africa.

Access to the coast

The Scramble for Africa and the administrative splits within colonial powers led, upon independence, to the creation of many landlocked countries, with no access to the global shipping lanes. Out of 49 countries, 16 are landlocked: Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Ethiopia, Central African Republic, Chad, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and South Sudan. And the largest country (in terms of land area), the Democratic Republic of Congo (the former Congo Free State), only has access to the sea (Atlantic Ocean) via a tiny 30-kilometre strip of land between the mainland of Angola (in the South) and the Cabinda enclave (which is part of Angola, in the North). Close to 300 million Africans (400 million if we add DRC) live in landlocked countries. Collier (2007) argued that being landlocked increases the likelihood that the country will be subject to ‘poverty trap’ dynamics, since it is associated with various costs.7 First, transportation costs are higher and trade with the rest of the world is limited for landlocked countries (Storeygard 2015). The costs of being landlocked are higher for those African countries that depend heavily on export proceeds from agriculture (e.g. Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda) or minerals (e.g. Chad, Zambia, Zimbabwe). Second, landlocked countries depend extensively on their neighbours for both exports and imports. Since the neighbours are themselves often unstable, African landlocked countries face serious challenges. For example, Zimbabwe exports to the rest of the world via the Beira corridor and port in Mozambique in the Indian Ocean. During the Mozambican civil war (1977-1992), access to Beira was severely limited or shut down altogether, impeding Zimbabwean exports from reaching world markets.

Likewise, almost all of Ugandan exports are channelled via the port of Mombasa in Kenya. The railroad connecting Mombasa to Uganda, the so-called Lunatic Express, has been blocked on many occasions by protests, or has stopped functioning because of conflict, harming Ugandan producers.

Country shapes and sizes

Herbst (2000) has argued that, by creating states with peculiar sizes and shapes, the Scramble for Africa has had sizable adverse long-run impacts. He also emphasises the ‘inappropriate’ location of capitals. Upon independence, the newly-minted entities, particularly the inefficiently large ones, found it difficult to broadcast power outside their capital centres. African countries have very low levels of state (fiscal and legal) capacity (Besley and Persson 2011). Because of the limited presence of courts and state authorities outside the capitals, many Africans settle disputes (especially over rural land) in tribal courts and seek the advice of traditional leaders and chiefs (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2015). Quite often the state cannot monopolise violence. In Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2014), we provide indirect evidence along these lines; showing that differences in country-wide institutions, across the national border, map into differences in regional development across the border, only when we look at (ethnic) areas close to the respective capitals. Using survey level data, we further show that proxies of state capacity, related to tax collection and policing, rapidly decay as one moves away from the capitals. In line with this, Campante et al. (2016) show that countries with isolated capital cities have lower quality institutions.

Ethnic composition (fractionalisation, polarisation, and inequality)

The Scramble for Africa has also inadvertently shaped the ethnic composition of the newly independent states. While the link between ethnic fractionalisation (the likelihood that two randomly drawn individuals of a country do not come from the same ethnic group) and development and/or conflict is weak, there is a tight relationship between ethnic polarisation (which takes the maximum value when there are two groups of equal proportions) and conflict (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol 2005, Esteban et al. 2012).

Alesina et al. (2016) show that ethnic-specific differences in economic prosperity and geographic endowments, which are highest in Africa, map into overall underdevelopment (see also Huber and Mayoral 2015). Alesina and Zhuravskaya (2012) show that ethnic segregation, which again tends to be higher in Africa than elsewhere, is linked to low levels of institutional development.

Conclusion

Research quantifying the impact of ethnic partitioning, state artificiality, and other features of the Scramble for Africa with formal econometric techniques and theory, is still in its infancy. The preliminary empirical findings of the economics literature bode well, however, with the case-studies and narratives of the African historiography highlighting the multi-faceted consequences of the Scramble for Africa. More research is needed to better understand how those colonial borders and colonial artefacts that survived decolonisation affect the present. And, since border artificiality and ethnic partitioning are not phenomena exclusive to the African continent, subsequent works could focus on other parts of the world, such as the Middle East.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J A. Robinson (2001), “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation”, American Economic Review, 91 (5), 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J A Robinson (2015), “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth”, in The Handbook of Economic Growth, edited by Philippe Aghion, and Steven. N. Durlauf, pp. 109.139. Elsevier North- Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Acemoglu, D, T Reed, and J A Robinson (2014), “Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone”, Journal of Political Economy, 122(2): 319–68.

Alesina, A, W Easterly, and J Matuszeski (2011), “Artificial States”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(2): 246-277.

Alesina, A, S Michalopoulos and E Papaioannou (2016), “Ethnic Inequality”, Journal of Political Economy, 124(2): 428-488.

Alesina, A and E Zhuravskaya (2011), “Segregation and the Quality of Government in a Cross-Section of Countries”, American Economic Review, 101(6): 1872-1911.

Asiwaju, A I (1985), Partitioned Africans. The Conceptual Framework, St. Martin Press, New York.

Besley, T and T Persson, (2011), “The Logic of Political Violence”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3): 1411-1445.

Blattman, C and E Miguel (2010), “Civil War”, Journal of Economic Literature, 48(1): 3-57.

Bluin, A (2016), Who Still Uses Pre-colonial Institutions? The Role of Colonial Policy and (Mis)Trust among Hutu and Tutsi, Working Paper, University of Toronto.

Bolt, J (2013), “The Partitioning of Africa”, in The History of African Development, edited by Ewout Frankema and Ellen Hillboom.

Campante, F R, Q-A Do, and B Guimaraes, (2016), “Capital Cities, Conflict, and Misgovernance”, Working Paper, Harvard University, Kennedy School of Government.

Collier, P (2007), The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Easterly, W and R Levine (2016) “The European Origins of Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Growth, 21(3): 225-257.

Esteban, J, L Mayoral, and D Ray (2012), “Ethnicity and Conflict: Theory and Facts”, Science, 336,858.

Frankema, E, J Williamson, and P Woljer (2015), An Economic Rationale for the African Scramble: The Commercial Transition and the Commodity Price Boom of 1845-1885, NBER WP 21213.

Herbst, J (2000), States and Power in Africa, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Huber, J D and L Mayoral (2014), Inequality, Ethnicity, and Civil Conflict, Working Paper, Columbia University, Department of Political Science

Jedwab, R and A Moradi (2016), “The Permanent Effects of Transportation Revolutions in Poor Countries: Evidence from Africa”, Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

La Porta, R, F Lopez-de-Silanes, and A Shleifer (2008), “The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins”, Journal of Economic Literature 46(2): 285-332.

Lowes, S and E Montero (2016), Blood Rubber: The Effects of Labour Coercion on Institutions and Culture in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Working Paper, Harvard University, Department of Economics.

Michalopoulos, S and E Papaioannou (2014), “National Institutions and Subnational Development in Africa”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1): 151.213.

Michalopoulos, S and E Papaioannou (2016), “The Long-Run Effects of the Scramble for Africa”, American Economic Review, 106(7): 1802-1848.

Michalopoulos, S and E Papaioannou (2017), “The Scramble for Africa and its Legacy”, New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, forthcoming.

Nunn, N (2008), “The Long Term Effects of Africa’s Slave Trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(1), 139-176.

Nunn, N (2016), “Understanding the Long-Run Effects of Africa’s Slave Trades”, In The Long Economic Shadow of History, Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou (eds.), VoxEU.

Nunn, N, and D Puga (2012), “Ruggedness: The Blessing of Bad Geography in Africa”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1): 20-36.

Mamdani, M (1996), Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Montalvo, J G and M Reynal-Querol. 2005. “Ethnic Polarization, Potential Conflict, and Civil Wars.” American Economic Review, 95(3): 796-816.

Murdock, G P (1959), Africa: Its Peoples and their Culture History, McGraw- Hill.

Pakenham, T (1991), The Scramble for Africa. Abacus, London, UK.

Storeygard, A (2015), “Farther Down the Road: Transport Costs, Trade, and Urban Growth”, Review of Economic Studies, 83(3): 1263-1295.

Wantchekon, L and O Garcia Ponce (2014), Critical Junctures: Independence Movements and Democracy in Africa, Working Paper, Princeton University, Department of Politics.

Wesseling, H L (1996), Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880-1914, Praeger, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Wimmer, A, L-E Cederman, and B Min (2009), “Ethnic Politics and Armed Conflict. A Configurational Analysis of a New Global Dataset”, American Sociological Review, 74(2): 316-337.

Endnotes

1 In the African context, Europeans applied forced-labour practices in Congo (Lowes and Montero 2016), Rwanda (Blouin 2016), and other countries; and in many cases they established extractive indirect-rule colonies and protectorates, where small ethnic minorities and local chiefs controlled the interior using brutal methods (e.g. Acemoglu et al. (2014), Mamdani 1996).

2 In Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016, 2017) we provide a detailed overview of the key events surrounding the Scramble for Africa. Pakenman (1991) offers a comprehensive account.

3 Frankema et al. (2015) point to the global developments during the Scramble for Africa, including the commodity price boom in the decades before the Berlin Conference of 1885 (the latter has come to symbolise the partitioning of the continent). Bolt (2013) discusses the key driving forces of the Scramble and the role of the steam boat, medical innovations, iron metallurgy, etc.

4 In line with this, Alesina, et al. (2011) estimate that around 80% of African borders follow latitudinal and longitudinal lines, more so than in any other part of the world.

5 Wantchekon and Garcia-Ponce (2016) discuss how differences in the type of independence movements have shaped subsequent political, institutional, and economic developments.

6 Alesina et al. (2011) estimate that partitioned groups constitute, on average, 40% of a country’s population.

7 Nunn and Puga (2012) show that distance to the coast correlates negatively with GDP per capita. Within Africa, this correlation is statistically indistinguishable from zero, most likely because landlocked countries were shielded from the ‘slave trades’.