One of the key targets at COP27 is to make “finance flows a reality”. “Providing, mobilising and deliver climate finance for developing countries is an urgent priority [..].”

The importance of scaling up sustainable finance is underscored by Dursun-de Neef et al. (2022) and Schoenmaker and Voltz (2022). At the COP27 debates, there will be demands for more climate aid from wealthy countries. Financing is set to be the make-or-break issue for this COP. Wealthy nations pledged to mobilise $100 billion a year by 2020, but are still about $17 billion short. Progress on delivery of the annual $100 billion will build more trust between developed and developing countries and make progress towards tackling the global climate change problem more probable.

Equity considerations have been a core rationale behind the pledge to provide $100 billion a year in climate finance to developing countries. The argument typically runs as follows: (1) developed countries have historically emitted more carbon, so bear a larger responsibility for the adverse impacts of climate change; and (2) developed countries are wealthier than developing countries, so must help poor countries with climate mitigation and adaptation. In the run-up to COP27, the call to offer compensation finance for “loss and damage’’ has become especially prominent. “Loss and damage” has become shorthand for the call for funding by wealthy countries for poor countries suffering the consequences of climate change. The matter has grown more urgent this year, marked by a succession of extreme weather events including the recent widespread flooding in Pakistan.

As UN Secretary-General António Guterres put it at the opening of COP27: “Loss and damage can no longer be swept under the rug. It is a moral imperative.”

While such equity considerations matter profoundly, they have so far, however, not proved to be a strong impetus for action, as the difficulties of garnering a mere $100 billion a year in climate finance for developing countries have demonstrated. Once one takes account of the benefits to each country from emission reductions brought about by replacing fossil fuels with renewables anywhere in the world, there is a much more direct impetus for action: self-interest! Indeed, the Coase theorem states that it is in the economic interests of a country A to pay a polluting country B to stop polluting if that makes country A better off. From a Coasian perspective, it is thus sound economic logic to pay polluters for the costs of replacing fossil fuels with renewables, if the benefits exceed the cost. Indeed, Coase provides a new perspective on and rationale for (foreign transfers of) climate finance. Tangible net benefits can be reaped even if only a coalition of the willing (e.g. a region) strikes a Coasian deal to phase out of fossil fuels. The larger the climate club in terms of the emissions it can avoid, the closer the net benefits of such a deal get to the large net benefits in a global deal to get rid of fossil fuels.

Looking back at COP26, two distinct discussions took place: (1) ending coal; and (2) providing $100 billion in climate finance a year for developing countries. Looking forward, at COP27 these distinct discussions should be merged. Climate finance to help build renewables should be made conditional on the commitment to end coal (and fossil fuels more generally). Indeed, only if climate finance for phasing in renewables happens concurrently with phasing out coal is energy supply maintained and the risk of carbon leakage (a salient concern if only a subset of the world strikes a deal to phase out coal) limited. Building conditionality into climate finance is key to achieve emission reductions and thus the benefits of providing climate finance. To be equitable, such conditionality must come with compensation for the opportunity costs of coal. Indeed, coal owners and coal workers must be compensated for their missed income. Retraining programmes must be funded to make workers qualified for employment in the replacement renewable industry.

The Great Carbon Arbitrage

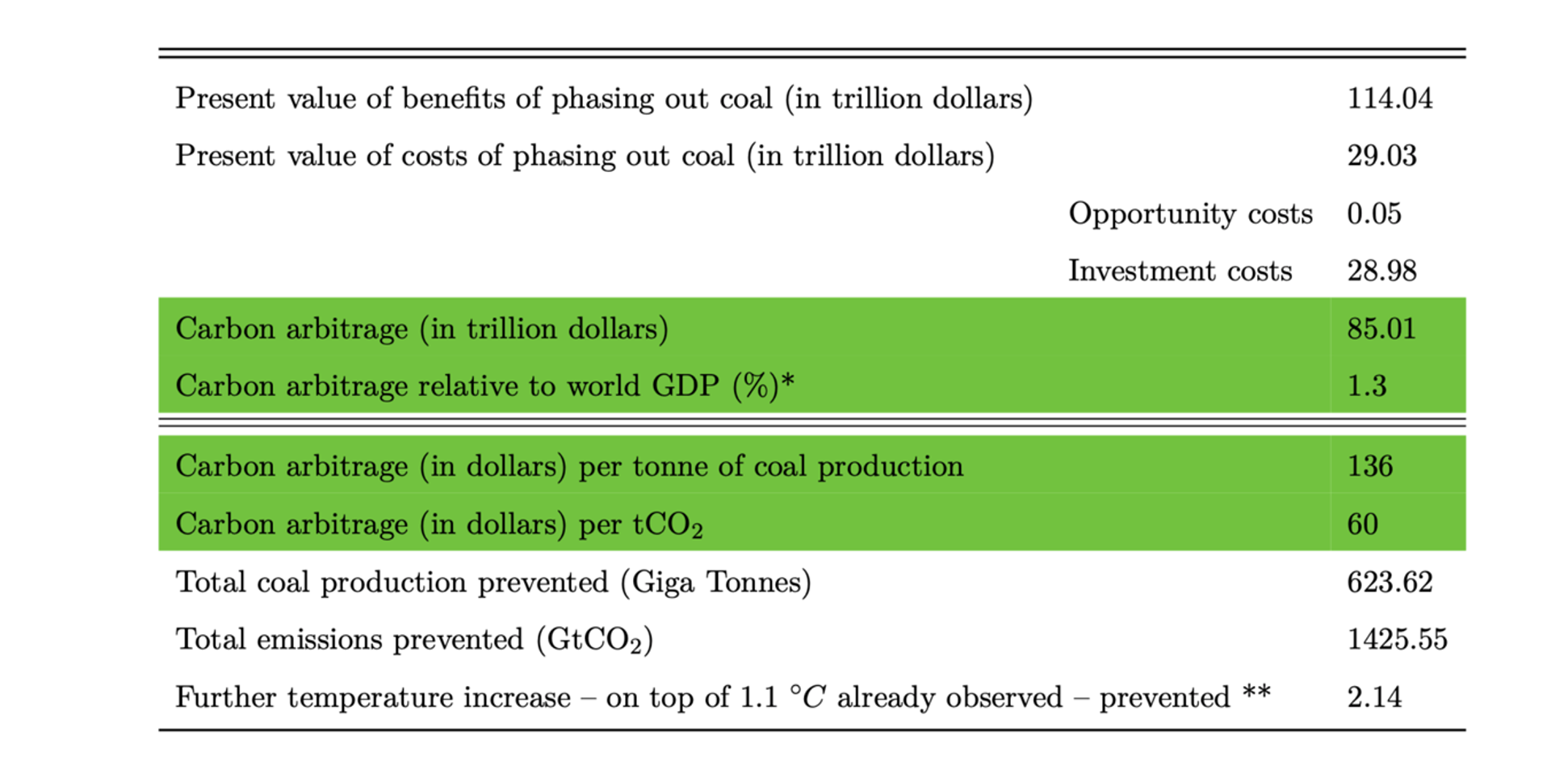

In a recent paper (Adrian et al. 2022), we study the net benefits from phasing out coal and replacing it with renewables. Our quantitative analysis makes a simple but important observation: phasing out coal and replacing it with renewables is not just a matter of urgent necessity to limit global warming. When its costs and benefits are considered, it also turns out to be a source of considerable net economic and social gain – the economic gain is around $85 trillion under a conservative estimate (see Table 1). Faced with the prospect of such an enormous gain, it is puzzling for any economist inculcated with the tenets of “there is no such thing as a free lunch” and “no money left on the table” how the world could indeed leave so much money on the table. Even faced with “high transaction costs” and “poorly defined property rights”, to use the main notions behind the Coase Theorem (Coase 1960), it is astonishing that a Coasian bargain of such proportions could be left untouched. One plausible explanation could be that the countries involved in working out a global agreement to phase out coal are not aware of the size of the benefits from such a phase-out, even taking into account the costs of replacing coal with renewables and the cost of compensating coal businesses and workers.

Benefits consist of the avoided climate damages from reduced emissions by shutting coal mines down early, and are under our baseline conservatively priced at an average social cost of carbon (SCC) of $80/tCO2. Costs consist of investment costs to build replacement renewable energy and compensate for opportunity costs of coal. We observe that the lion share of costs consists of the investment costs in renewables (at $29 trillion),

while only a small part consists of costs to compensate for the opportunity costs of coal (at $50 billion).

The quantified global opportunity costs of coal remain small even when we consider a broader definition of opportunity costs that includes not only missed revenues to coal owners from shutting mines down early, but also compensation for missed wages of coal workers losing their jobs in the coal phase out (for the duration of five years while they seek employment in other industries or retire early) and compensation for retraining costs to qualify for employment in other industries (e.g. the renewable industry). These broader opportunity costs bring our baseline estimate of the global opportunity costs of coal from $50 billion up to $331 billion (of which $275 billion is for lost wages and $7 billion for retraining). To our knowledge, this is the first valuation of the net global benefits from replacing coal with renewable energy.

Table 1 Net benefits of a global phase out of coal

In practice, obstacles to bargaining or poorly defined property rights can prevent Coasian bargaining to strike a global agreement on climate finance to replace coal with renewables, but our point is that in light of the large net gains we identify there should be renewed efforts to lift these obstacles. We point to promising avenues to overcome such obstacles and discuss how to make the funding to replace coal with renewables in the economic interests of all key stakeholders involved (i.e. governments, investors, and coal communities). In particular, we identify blended climate finance as a promising avenue to catalyse public investments.

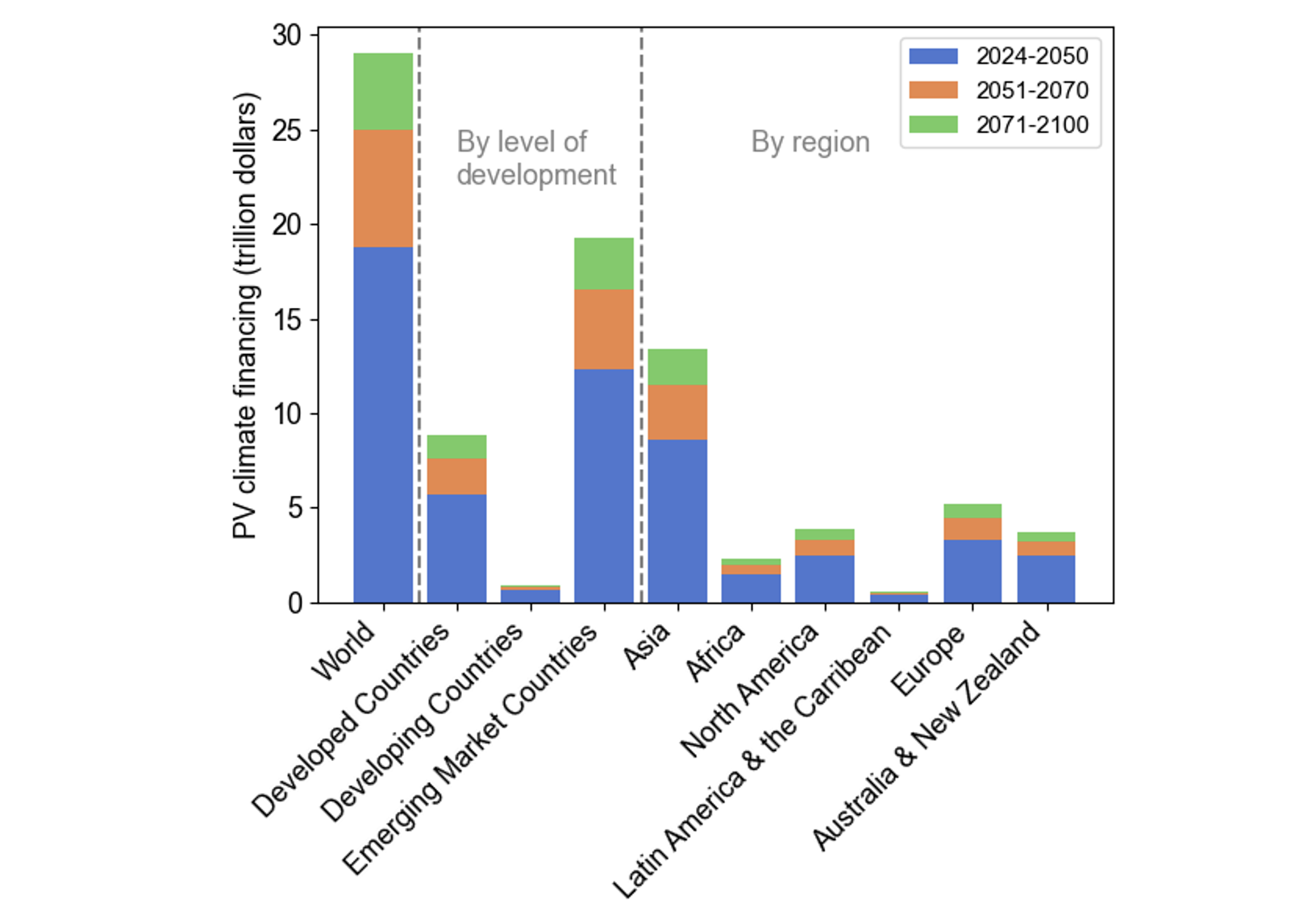

“Here is why blended finance matters – enormously. The beauty of this concept is leverage: if a small pot of multi-lateral development banks or western aid provides the first-loss tranche for investments to replace coal with renewables, it could attract a much larger dollop of private sector capital” (Tett 2022). With a 1:9 ratio of catalytic public to private funding, $26 trillion out of the $29 trillion could thus be raised via capital markets, while governments would only have to invest by around $2.9 trillion to enhance the capacity of MDBs to invest in the equity tranches. In our paper, we quantify climate financing needs for replacing coal with renewables across countries in the world.

Figure 1 Climate finance needs to replace coal with renewables (present value)

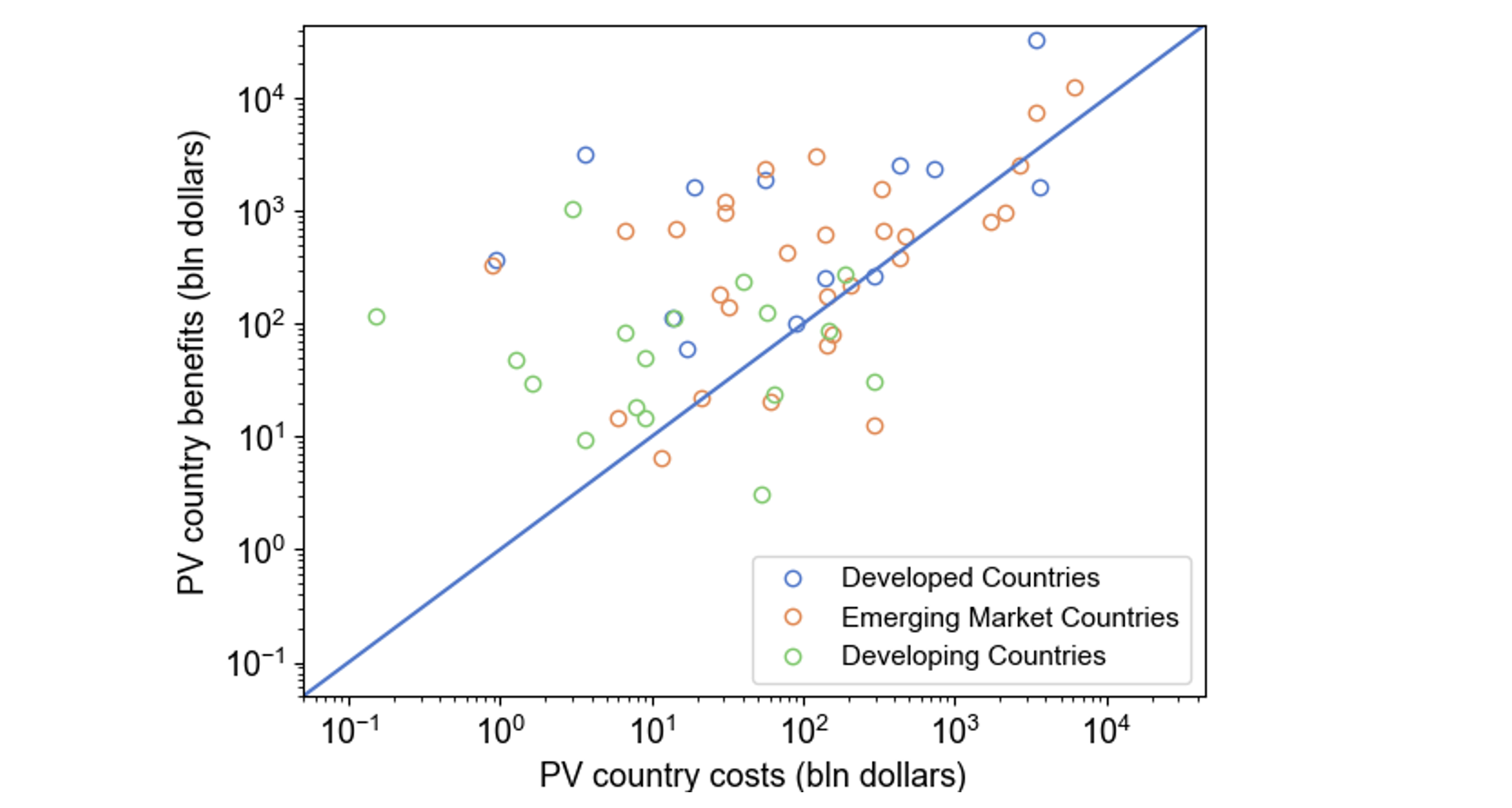

It seems a reasonable baseline under Coasian bargaining that each country cover its own costs to domestically replace coal with renewables. We find that it is in the economic interest of most countries to participate in a global deal to end coal, even in absence of cross-country compensatory transfers (see Figure 2). The benefits for each country from a global deal to phase out coal are given by the quantity of avoided emissions times the country-level SCC (estimated by Ricke et al. 2018).

This multiplication tells what share of the global benefits of avoided climate damages accrues to each country, capturing that impacts of climate change are unevenly felt across countries.

Figure 2 Country-level costs and benefits in a global deal to phase out coal (present value)

As noted, contributions to help cover foreign climate finance needs may be called for based on equity considerations. Such equity considerations have so far not proved to be a strong impetus for action, however. Once one takes account of the benefits to each country from emission reductions brought about by replacing coal with renewables anywhere in the world, there is a much more direct impetus for action: self interest. Indeed, the Coase theorem states that it is in the economic interests of a region A to pay a polluting region B to stop polluting if that makes region A better off. Take America as an example of region A and Africa as an example of region B (see Figure 3), to illustrate how climate financing from rich regions to poor regions is, in fact, enlightened self-interest!

We observe that the present value of investments Africa would need to make to replace its coal with renewables is $231 trillion (of which 90% could be drawn from capital markets if a successful blended finance arrangement is in place). The benefit to Africa in a global deal to phase out coal is given by $3.1 trillion dollars in avoided climate damages, while the benefit to Africa from in a deal that sees its own coal being phased out is $0.2 trillion in avoided damages. In both cases, benefits are computed by taking the collective SCC of Africa and multiplying that by the size of avoided emissions, which then gives an estimate of avoided losses (due to climate change) to Africa’s GDP. Africa may not be able to afford to spend $2.3 trillion to end coal – as recent foreign climate finance offered by rich countries to help South Africa phase out coal indicates (Pilling 2022). Given the greater historical emissions of rich countries, it may also not be fair for Africa to pay for its own coal phase out. The left panel of Figure 3 shows that rich regions, such as North America and Europe, stand to benefit enormously if Africa were to phase out coal. The orange circle with the green dot inside shows the benefits to North America of Africa's coal phase out are around $7.2 trillion; the benefits to Europe of Africa’s phase out are around $1.6 trillion. Hence, it is squarely in rich countries’ interest to offer climate finance to help Africa with its coal phase out. With blended finance, these rich countries would only have to pay 10% of $2.3 trillion ($0.23 trillion) in present value terms to do so.

Critical for benefits to materialise is that rich countries offer finance to build out renewables, as well as funding to compensate for the opportunity costs of coal of developing countries, conditional on the commitment to end coal. Otherwise, no emission reductions may take place and benefits to rich countries in terms of avoided climate damages are not realised. Phasing in renewables and phasing out coal concurrently is moreover critical to ensure sufficient energy supply for Africa.

Figure 3 Present value of costs to phase out coal in one region and present value of benefits this brings both to the region that is phasing out coal (right part), as well as other regions in the world (left part)

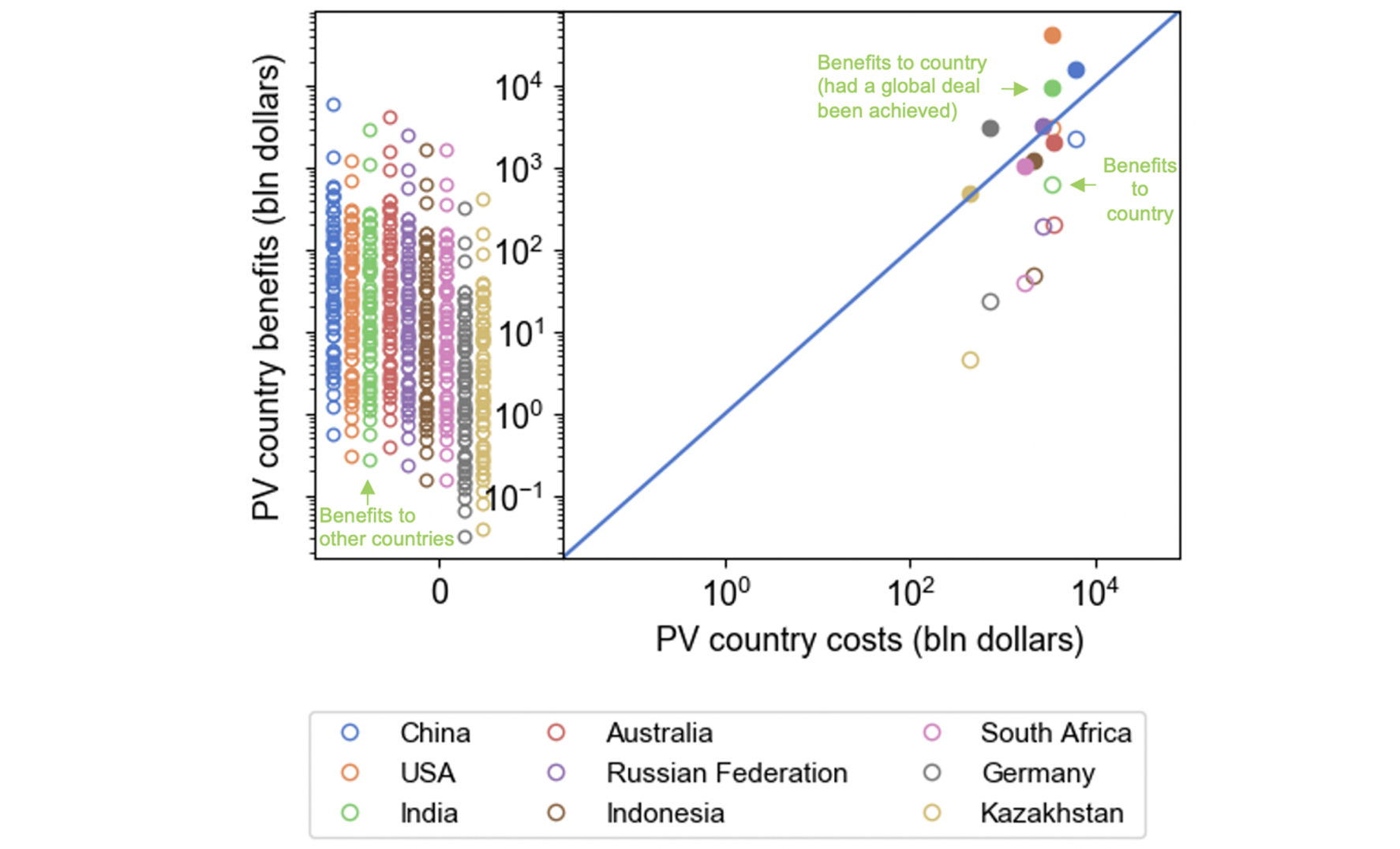

Similarly, it can be in the economic interest of rich countries to help pay for the costs of replacing coal with renewables in the most coal-reliant countries (see Figure 4), such as India, South Africa, and Indonesia.

Figure 4 Present value of costs to phase out coal in one of the top-9 coal countries and present value of benefits this brings both to the country that is phasing out coal (right part), as well as other countries in the world (left part)

Big picture, our conceptual contribution is that paying the polluter – via climate finance – to stop polluting (as is happening now, for example, in South Africa and Indonesia) results in a Coasian bargain. Coase won the Nobel prize for his insight that paying the polluter to stop polluting may make you better off. But, to the best of our knowledge, no work has linked his theory to the idea that the provision of climate finance could result in a Coasian bargain. No work has quantified whether such a bargain exists. Our empirical contribution it to provide the first quantification of the costs of climate finance to end coal and the net benefits this brings to different countries.

Conclusion

While the rationale for climate finance for developing countries has so far focused on equity considerations, we identify a new rationale: self-interest. Rich countries are made better off by helping poor countries phase out coal. For climate finance to be effective, financing for renewables, as well as compensation for the opportunity cost of coal, should be made conditional on the phase out of coal, such that substantive emission reductions take place and tangible benefits are felt in terms of avoided GDP losses (from climate damages) for rich countries. It seems to us that the most probable way to make “finance flows a reality” at COP27 is to make countries aware of the net gain they can reap from financing the phase out of coal.

By highlighting the net gain countries obtain by providing climate finance, while also still emphasising equity considerations, we stand the best chance to make finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development (Article 2c of the Paris Agreement).

References

Adrian, T, P Bolton, and A Kleinnijenhuis (2022), “The great carbon arbitrage”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17654.

Coase, R H (1960), “The problem of social cost”, The Journal of Law and Economics 56(4): 837– 877.

Dursun-de Neef Ö., S Ongena and G Tsonkova (2022) “Green versus sustainable loans: The impact on firms’ ESG performance”, VoxEU.org, 03 November.

Pilling, D (2022), “The costs of getting South Africa to stop using coal”, Financial Times, 1 November.

Ricke, K, L Drouet, K Caldeira and M Tavoni (2018), “Country-level social cost of carbon”, Nature Climate Change 8(10): 895-900.

Schoenmaker D and U Volz (2022), “Scaling up sustainable finance and investment in the Global South”, VoxEU.org, 1 November.

Tett, G (2022), “The Flood of Green Finance must be diverted from the West”, Financial Times, 27 October 27.