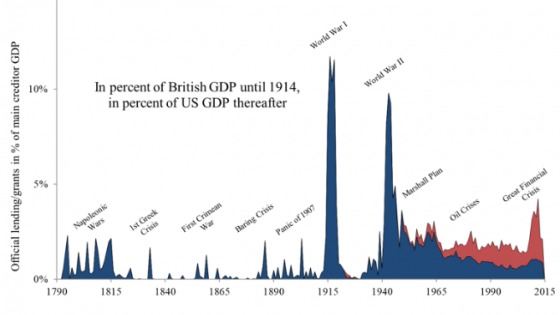

Global crises, like the unfolding one, have been repeatedly times of official, state-driven finance, including at the international level (Kindleberger 1984, Bordo and Schwartz 1998, Eichengreen 1995). As we document here, during wars and other major shocks, governments have been willing to transfer significant sums of loans and grants to their allies and other states in need. This was particularly true during the two world wars, when the US and the UK extended unprecedented amounts of international loans and grants to other sovereigns. The total international bailout packages of 2008-2012 were small compared to the scale of the international transfers during wartime (Figure 1).

For example, during 1940-1944 governments mobilised international grants and loans on the order of 10% of US GDP (per year). This was at a time when advanced economies were recording double-digit fiscal deficits. Today, these magnitudes correspond to about $2,000 billion in annual flows. Those are enormous sums.

A panoramic view of two centuries of government-to-government lending

Our evidence comes from a multi-year research project on international official lending, which we define as credits granted between the official sector (governments and between central banks) of different nations. The growing role of multilateral official institutions is also included. Our data indicate that, over the past two centuries, official creditors have played an important (and occasionally dominant) role in international finance. While some episodes of official international lending and assistance are well known (the Marshall Plan, IMF/EU bailouts during the Global Financial Crisis), the broader trajectory of official lending remains largely obscure. Existing datasets on official international lending and grants typically have a narrow focus on development aid, i.e. concessionary lending, or they have limited coverage, usually starting in the 1980s. The history of official (sovereign-to-sovereign) lending remains mostly forgotten.

Our forthcoming research paper (Horn et al. 2020) shows that official lending by governments, central banks, and multilateral institutions is much larger than commonly known. Since 1800, official capital flows have frequently exceeded total private cross-border flows. This is especially true during times of war, economic crises, and natural disasters, when private flows decline often abruptly. In many such instances, official actors are the only ones engaged in international lending.

Based on a rich new loan-level dataset that spans more than two centuries, our analysis explores trends and cycles in official lending with a particular focus on periods of global turmoil. Our data cover the international lending transactions of 134 creditor countries and 56 international and regional financial organisations. The database builds on hundreds of sources, including international treaties, budget accounts, the World Bank, and archival material. In total, we identify more than 230,000 official loans, grants and guarantees from 1790 to 2015, with total commitments amounting to more than $15 trillion (in constant 2015 terms), which is similar to the total outstanding US government debt as of 2015.

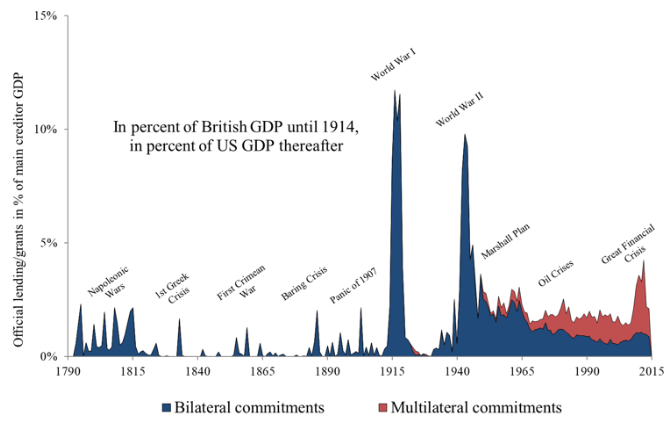

Figure 1 Official international lending, 1790–2015 (bilateral and multilateral)

Note: Gross aggregate official commitments by multilateral (in red) and by bilateral creditors (in blue) in percent of the main creditor’s GDP. The data includes commitments through grants, loans, and guarantees, but excludes official portfolio investments and central bank swap credit.

Source: Horn et al. (2020).

As Figure 1 highlights, the major surges in official lending occurred during international wars, in particular the Napoleonic wars and the two world wars of the 20th century. Lending during these global conflicts by far exceeded lending during global financial crises or major natural disasters. This feature speaks to some of today’s debates on the international financial system. We typically think of official finance as a complementary type of capital flows in the context of development aid and financial crisis bailouts or support. But this modern view largely a reflects the fact that most advanced economies have enjoyed 70 years of relative peace, unencumbered by major global catastrophes (Harari 2011) – at least not until 2020. This also helps explain why most of the official lending of the past decades has gone to emerging economies or developing countries. Historically, however, today’s advanced economies were the main recipients of international official loans (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Official international lending: Advanced vs developing country recipients

Note: Total gross official international loan and grant flows (government to government, including bilateral and multilateral institutions). Includes commitments through grants, loans and guarantees, but excludes official portfolio investments and central bank swap credit.

Source: Horn et al. (2020).

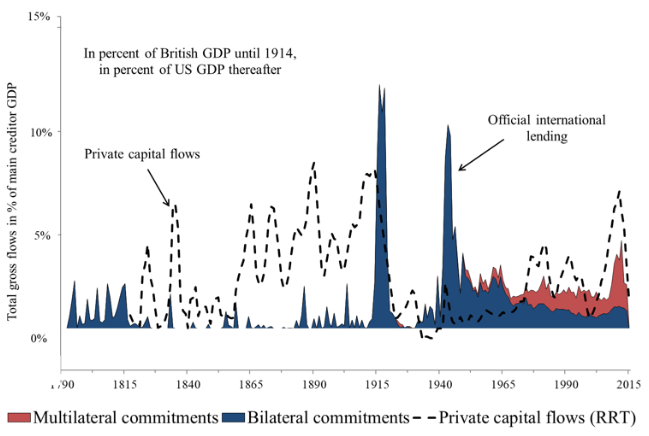

When private capital flows retrench, official capital flows surge

By comparing our novel data on official flows with previously assembled long-run data on private international capital flows (Reinhart et al. 2016, 2020), we show that both series are negatively correlated. Figure 3 shows that official capital flows are highest when private capital flows dry out.

Four different types of episode are played out in the figure, depending on whether the official or the private sector is the prime mover.

As for governments, for one, wars grind private capital flows to a halt by rendering former destinations unreachable, as they are now potential either enemy combatants or blockaded allies. It can also make them unattractive investments because of the risk of confiscation or loss as governments direct or confiscate resources for the war effort. Official lending steps up to fund allies in the pursuit of a common goal, to keep potential enemies on the side lines, or to offer humanitarian assistance to the vanquished.

A second class of government interventions follow disasters other than wars. National or man-made calamities may block the physical flow of funds or make the afflicted economies uninvestable. Governments or quasi-official institutions step in to provide humanitarian assistance either out of generosity or the real-political desire to keep the nation within a sphere of influence. Wars and other disasters produce a negative correlation, but the former are associated with shifts of higher magnitude in the figure.

Third, a more routine form of government intervention comes when private capital flows are forbidden or steeply limited, as in the Bretton Woods arrangement after WWII or in China in the early years of its WTO accession. In this case, official flows are the only game in town, usually in the pursuit of economic or geopolitical aims.

Fourth, it is sometimes the decisions of private investors to stop funding that puts official capital in motion, again resulting in a negative correlation between official and private flows. A sudden stop of capital prompting an exchange rate or banking crisis may trigger action to assist trading partners, as with bilateral US aid to Mexico in 1995, regional loans during the euro crisis, or multilateral lending (e.g. IMF programmes). Self-interest may lurk behind these interventions. Official loans and grants to troubled nations can be means by which the providing government assures that their domestic institutions, exporters and investors are repaid and as a way to reduce the negative spillovers to their own economy (Tirole 2015, Gourinchas et al. 2019).

Figure 3 Official versus private capital flows, 1790–2015

Note: The blue/red areas correspond to total official commitments (see Figure 1). In comparison, the dashed black line shows the magnitude of global private cross-border capital flows as measured by Reinhart, Reinhart and Trebesch (2016, 2020). All series are scaled by main creditor GDP.

Source: Horn et al. (2020) and Reinhart et al. (2016, 2020)

The return of official lending: New creditor powers, new safety nets, and central bank swap lines

It is not widely appreciated that we are witnessing a pronounced comeback of official lending in recent decades. China’s rise as an international creditor, in particular, has been underestimated due to a lack of data and transparency (see also Horn et al. 2019). But China’s official lending boom has been part of a general rise of new creditor powers, especially emerging markets such as the Russia, India, Brazil or the Arab oil states. In addition, dozens of new official lending institutions were founded since WWII, including a range of regional development banks and regional financial arrangements in Asia, Africa and South America. The result has been a notable increase in “South-South” official sovereign lending. It remains to be seen whether this trend continues given today’s developments. What is clear from the data: the vehicles for bilateral, regional and multilateral official lending have never been so plentiful and diverse as today. The global financial safety net is large and diverse (Scheubel and Stracca 2016).

Crucial, in the current context, is that we are also seeing a resurgence of official cross-border financing via central banks. Since the financial crisis of 2008 the Federal Reserve Bank, the ECB and the Bank of Japan have granted record amounts of ‘swap lines’ via a network of standing credit lines that allow drawing overnight foreign currency loans (Bahaj and Reis 2019). These developments are reminiscent of the frequent cross-border central bank lending during the gold standard era pre-WW1 and in the interwar years. It is unsurprising that swap lines have now been reactivated on a large scale.

Concluding remarks

Pandemics have been a part of history since ancient times. The current global and abrupt dislocation, however, makes this situation very hard to compare historically. The parallels to the world wars are limited, but we have shown that, over the past 200 years, countries have been willing to mobilize substantial amounts in cross-border lending during times of disaster. Time will tell whether this time will be different or not.

References

Bahaj, S and R Reis (2018), “Central bank swap lines”, VoxEU.org, 25 September.

Bordo, M D and A J Schwartz (1998), "Under what circumstances, past and present, have international rescues of countries in financial distress been successful?", NBER Working Paper 6824.

Eichengreen, B (1995), Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression 1919-1939. Oxford University Press.

Gourinchas, P-O, P Martin and T Messer (2019), “The Economics of Sovereign Debt, Bailouts and the Eurozone Crisis”.

Harari, Y (2015), Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Vintage Books.

Horn, S, C M Reinhart, and C Trebesch (2019), “China’s Overseas Lending”, NBER Working Paper No. 26050.

Horn, S, C M Reinhart, and C Trebesch (2020), “Coping with Disaster: Two Centuries of International Official Lending”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14902.

Kindleberger, C P (1984), A Financial History of Western Europe, Routledge.

Reinhart, C M, V Reinhart, and C Trebesch (2016),” Global Cycles: Capital Flows, Commodities, and Sovereign Defaults, 1815-2015”, American Economic Review 106(5): 574–80.

Reinhart, C M, V Reinhart, and C Trebesch (2020), “Capital Flow Cycles: A Long, Global View”, mimeo.

Scheubel, B, and L Stracca (2016), “What do we really know about the global financial safety net?” Vox Column, 4 October.

Tirole, J (2014), "Country Solidarity in Sovereign Crises", American Economic Review 105(8): 2333–63.