There are growing concerns about how to induce companies to do business ‘responsibly’ (Liang and Renneboog 2017). This call is particularly strong for environmental concerns, where ‘responsibility’ usually means any of the following three elements: (i) preventive decisions in day-to-day operations to avoid disasters, (ii) compliance with regulatory standards, and (iii) consideration for long-term impact, potentially at the cost of short-term profit.

In a recent paper (Vuillemey 2020), I study how firms use a key feature of corporate law – limited liability – to evade these corporate responsibilities. I focus on the shipping industry, which is the backbone of globalisation, as it carries 80% to 90% of all goods globally. Furthermore, this industry faces both large risks in day-to-day operations (oil or chemical spills) and for the long run (recycling of large and dirty tankers or containerships). My main finding is that shipping firms are being structured almost systematically over the past four decades to minimise their responsibility.

Liability evasion using one-ship subsidiaries

The first dimension of corporate responsibility is the ability to avoid, and eventually face the consequences of, disasters – that is, rare events with extremely negative consequences. Increasingly over the past decades, shipping companies are being structured to minimise potential tort liabilities. Indeed, ships are almost always owned by limited-liability subsidiaries of corporate groups. In other words, legal ownership and ultimate ownership are dissociated. This means that, in case of a disaster, the subsidiary is held liable while the parent company is in principle insulated.

Evasion from potential liabilities is further achieved by minimising the size of assets in each subsidiary; typically, a group creates one different subsidiary for each ship. In 2020, 89.97% of all registered owners of ships globally are one-ship subsidiaries. This means that for groups holding multiple ships, damages caused by one ship cannot be paid for using resources generated by the operation or sale of other ships.

This structure explains why, in some famous cases of oil spills, establishing liability proves so difficult. Consistent with the view that liability evasion is a dominant force, I show that older and riskier ships are more likely to be owned by one-ship subsidiaries.

Evasion of regulatory standards using flags of convenience

The second dimension of corporate responsibility is compliance with regulatory standards, such as safety or environmental standards. While such standards exist, they can be evaded by registering ships with flags of convenience – that is, by using flags of jurisdictions that sell the right to use their flag but do not verify the compliance of ships with international standards.

Theoretically, the issue of flags of convenience is closely related to limited liability: the possibility to dissociate a corporate group into many subsidiaries also allows a group to choose where to locate the subsidiaries and, thus, which regulatory framework to subject to.

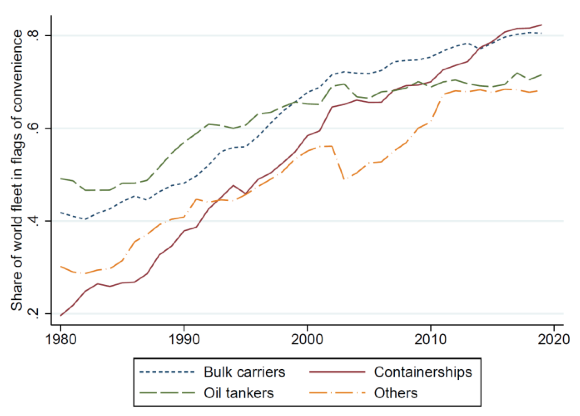

The use of flags of convenience has been booming over the past four decades (Figure 1). For example, among containerships, flags of convenience represent 82.3% of the global tonnage in 2019, as opposed to only 19.6% in 1980.

Figure 1 The growth of flags of convenience

The widespread use of flags of convenience implies that the world fleet is composed of older and riskier ships, which are more likely to be lost at sea. Consistent with the idea that global competition pushes firms to cut costs and seek regulatory evasion, I find that the adoption of flags of convenience is more likely when freight rates are low, and for shipping companies that are financially constrained.

Evasion of long-term responsibilities with last-voyage flags

The third dimension of corporate responsibility is consideration for long-term impact. Long-term responsibility is key in the shipping industry since old ships are large and often dangerous waste.

I show two trends in the decisions related to end-of-life ships. First, globally almost all ships are dismantled in poor environmental conditions after being ‘beached’ on the shores of Bangladesh, India, or Pakistan.

Second, a fast-growing number of shipping companies use ‘last-voyage flags’, most likely in an attempt to hide such dirty practices: ships are sold to a third party just for the last voyage to a beaching yard. In doing so, shipping companies get paid for the value of a ship’s raw materials but do not assume any of the responsibilities associated with toxic wastes or oil residuals (which end up at sea).

While last-voyage flags were close to non-existent in the early 2000s, they represented 55.2% of all end-of-life ships globally in 2019 (Figure 2). This practice is again related to limited liability: in this case, shipping companies evade responsibilities by outsourcing dirty decisions to small, limited-liability third parties.

Figure 2 The growth of last-voyage flags

Some implications

These findings highlight a downside of globalisation: the drop in transportation costs over the past decades was partly achieved via the evasion of shipowners’ responsibilities, including environmental liabilities. Importers and exporters may not have been paying the true cost of their activity. Using the terminology by Rodrik (1997), globalisation may have gone ‘too far’.

My results also raise questions about the use of limited liability in parent-subsidiary relationships, particularly for tort liabilities. Indeed, limited liability enables group owners to externalise damages to society. The associated costs are more severe than those generated by standard risk-shifting (Jensen and Meckling 1976) since tort creditors are not contractual creditors and so cannot take action to protect themselves. Based on similar reasoning, some legal scholars have challenged the use of limited liability for torts (Hansmann and Kraakman 1991) or for fully-owned subsidiaries (Blumberg 1986). In general, limited liability and corporate responsibility may be much more closely linked than previously thought.

References

Blumberg, P I (1986), “Limited liability and corporate groups”, Journal of Corporation Law 11: 573–631.

Hansmann, H, and R Kraakman (1991), “Toward unlimited shareholder liability for corporate torts”, Yale Law Journal 100: 1879–934.

Jensen, M C, and W H Meckling (1976), “Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–36.

Liang, H, and L Renneboog (2017), “On the foundations of corporate social responsibility”, Journal of Finance 72: 853–910.

Rodrik, D (1997), Has globalization gone too far? Washington DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Vuillemey, G (2020), “Evading corporate liabilities: Evidence from the shipping industry”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15291.