Could COVID-19 lead to a global food crisis? As the virus spreads around the world, there are concerns that global food security could come under pressure (Laborde et al. 2020, Martin and Glauber 2020, Torero 2020). Food production is currently high, but it could be negatively impacted by increased workers’ morbidity, disruption in supply chains, and containment measures. Governments’ attempts to restrict food exports to meet domestic needs could make things much worse.

In a new paper (Espitia et al. 2020a), we analyse how world trade in food could be affected by COVID-19 and escalating export restrictions. We quantify the initial shock due to the pandemic under the assumption that products that are more labour intensive in production are more affected through workers’ morbidity and containment policies. We then use the logic of the multiplier effect of trade policy to estimate how escalating export restrictions to shield domestic food markets could magnify the initial shock.

Initial conditions in global food markets are good

Back in 2006-2007 and then again in 2008-2011 a series of shocks created a gap between global demand and global supply of food, leading to sharp increases in food prices (Figure 1). Many governments intervened implementing export restrictions that contributed to reduce global supply, leading to even higher food prices. The situation today is in part different: production levels of major staples are above the average of the past five years, oil prices are low, and stock levels relative to consumption for major grains are 70-100% higher than in the late 2000s (Voegele 2020). Global food prices have been relatively stable in recent years and they have remained low in the first months of 2020.

Figure 1 Food Price Index (January 2000 – February 2020)

Source: International Monetary Fund Primary Commodity Prices (January 2000-February 2020). \

Note: Food Price Index, 2016 = 100, includes Cereal, Vegetable Oils, Meat, Seafood, Sugar, and Other Food (Apple (non-citrus fruit), Bananas, Chana (legumes), Fishmeal, Groundnuts, Milk (dairy), Tomato (vegetables)).

But COVID-19 could negatively impact the global export supply of food

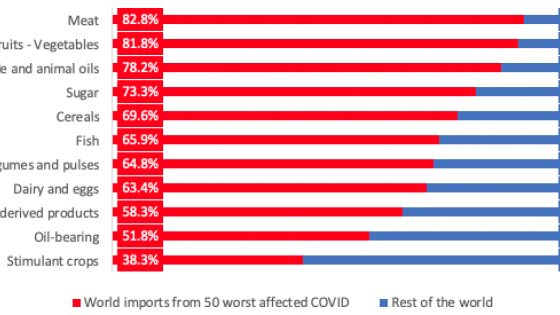

Countries most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are top exporters of food products.1 A new World Bank database (Espitia et al. 2020b) shows that top 50 countries most affected by COVID-19 represent on average 66% of world export supply of food products. Their share of world exports goes from 38% in stimulant crops to more than 75% in vegetable and animal oils, fresh fruits, and meat (Figure 2). Exports of key staples such as corn, wheat, and rice are highly concentrated among top-50 countries most affected by COVID-19.

Figure 2 World imports from top-50 countries most affected by COVID-19

Source: Espitia et al. (2020b), “Database on COVID-19 trade flows and policies”.

We provide a first assessment of the initial shock that COVID-19 could have on world food markets. We assume that the initial shock in supply proportionally increases with the weight of low skill labour in total value added in exports. Intuitively, workers’ morbidity and the need for social distancing will more strongly affect the supply of products that are more labour intensive, such as paddy rice, or the supply of products that have crucial labour-intensive stages, such as the processing of fish.3 In our baseline scenario, we use data from Chinese food exports in January and February 2020 to inform the potential shock for the 50 most affected countries.

Under these assumptions, we find that in the quarter following the outbreak of the pandemic, the global export supply of food could decrease between 6% and 20% (Figure 3). Many important staple foods, including rice, wheat and potatoes could have drops in export supplies of over 15%. Given the substantial uncertainty about the extent of the current health crisis, we also consider an upward and a downward scenario, where initial export supply shocks are respectively 10% higher and lower compared to the observed declines in China’s food exports.

Escalating export restrictions would magnify the initial shock by a factor of three

As of end of April, over 20 governments have imposed some form of restrictions on food exports – this is substantially less than the restrictions on COVID-19 relevant medical products (EUI-GTA-WB 2020). But as food prices increase due to the initial COVID-19 shock, governments may be tempted to use trade policy to stabilise domestic prices. Intuitively, although restrictions mitigate pressures on domestic food markets, they reduce supplies in the world market, thus driving prices up. In response, other governments would likely retaliate by imposing new export restrictions, leading to a multiplier effect (Giordani et al. 2020).

Figure 3 Food export supply and price effects of COVID-19 under different trade policy scenarios

Source: Espitia et al. (2020a).

Under the baseline (China-like) scenario for the initial shock, we find that escalation in export restrictions would lead to a decline in the world food export supply by 40.1% on average in the quarter following the outbreak of the pandemic while global food prices would increase by 12.9% on average. Price of key staples such as fish meat, oats, vegetables and wheat and meslin would increase by 25% or more. In the downward and upward scenarios, global export supply of food under uncooperative trade policies would decrease between 21% and 55.4% during the quarter following the outbreak of the pandemic. Food prices would increase between 6.6% and 17.9% on average (Figure 3).

Import food dependent countries would be the most affected

The negative effects of COVID-19 and export restrictions on food markets would be primarily felt by the poorest countries. We find that most affected import food dependent countries include Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Yemen, and Cuba, which would experience increases in average food prices ranging between 15% and 25.9% (Figure 4). For cereals, developing and least developed import food dependent countries would see price increases of up to 35.7%. While today several factors may contribute to mitigate food price increases (higher buffer stocks for food staples, lower oil price), poverty could rise as a result of the crisis making even smaller increases in food prices a threat to food security in developing countries.

Figure 4 Increases in food prices for import food dependent countries, retaliation scenario

Source: Espitia et al. (2020a).

Policy choices matter

Governments can avoid these negative outcomes. Restrictions to exports are inherently beggar-thy-neighbour policies, which is why they induce retaliation rather than cooperation. A first-best approach would consist of actions aimed at minimising the disruption to food supply, such as ensuring that workers in food sectors can continue producing under good and secure health conditions, removing bottlenecks that impair food supply chains, and ensuring that trade in key inputs in food production can smoothly flow across borders. This approach, by increasing the domestic supply of food, would reduce global supply shortages and mitigate price surges, thus having a positive spillover effect on other countries.

Editors' note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group.

References

Aguiar, A, M Chepeliev, E Corong, R McDougall and D van der Mensbrugghe (2019), “The GTAP Data Base: Version 10”, Journal of Global Economic Analysis 4(1): 1-27.

Espitia, A, N Rocha and M Ruta (2020a), “Covid-19 and Food Protectionism: The Impact of the Pandemic and Export Restrictions on World Food Markets”, World Bank working paper.

Espitia, A, N Rocha and M. Ruta (2020b), “Database on COVID-19 trade flows and policies”, Washington DC: World Bank.

EUI-GTA-WB (2020), “Covid-19 Trade Policy Monitoring: Food and Medical Products”.

Giordani, P, N Rocha and M Ruta (2016), “Food prices and the multiplier effect of trade policy”, Journal of International Economics 101 : 102-122.

Laborde, D, W Martin and R Vos (2020), “Poverty and food insecurity could grow dramatically as COVID-19 spreads”, International Food Policy Research Institute, April 16.

Martin W and J Glauber, (2020), “Trade policy and food security”, in R Baldwin and S Evenett (eds), COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work, London: CEPR Press.

Torero Cullen, M (2020), “Coronavirus, food supply chains under strain: what to do?”, Food and Agriculture Organization, March 24.

Voegele, J (2020), “Three imperatives to keep food moving in a time of fear and confusion”, World Bank Voices, April 3.

Endnotes

1 Most affected countries are defined based on information from the World Health Organization on total number of confirmed cases.

2 To account for these heterogenous effects across countries and products, we rely on data at the country-product level on the share of low-skill workers in the total value added in exports (Auguiar et al. 2019).