The share of firms in Japan adopting teleworking (working from home) has been low, in spite of the prevalence of long commutes. According to a firm survey conducted by RIETI, fewer than 10% of Japanese firms adopted teleworking in 2019. However, it has increased suddenly with the COVID-19 shock. The rapid diffusion of teleworking is not limited to Japan; it is a worldwide phenomenon.

In this respect, particularly if we consider the possibility of a prolonged or recurring COVID-19 outbreak, improving productivity at home is important to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic on the economy. However, evidence on the productivity of teleworking is limited. In this column, I present new evidence from Japan and discuss its policy implications.

Teleworking and productivity

There have been some studies on the impact of teleworking on productivity for specific occupations. Bloom et al. (2015), for example, present evidence from a field experiment with call centre employees in China that teleworking enhanced total factor productivity (TFP) of the organisation. The positive effect on productivity arises from both improvements in individual workers’ performance and from reductions in office space. In contrast, Battiston et al. (2017), exploiting a natural experiment with a public sector organisation in the UK, find that productivity is higher when teammates are in the same room and that the effect is stronger for urgent and complex tasks. They suggest that teleworking is unsuitable for tasks requiring face-to-face communication. Dutcher (2012), based on an experimental approach, indicates that telecommuting may have a positive impact on the productivity of creative tasks but a negative impact on the productivity of dull tasks.

These studies suggest that productivity from teleworking depends on the characteristics of occupations and specific tasks undertaken. As an extreme case, for service jobs requiring physical contact with customers – such as doctors, nurses, hairdressers, and restaurant waiting staff –productivity from teleworking is prohibitively low. Therefore, the current increase in teleworkers is mainly limited to ordinary white-collar workers. These workers are important drivers of economic performance in advanced economies, but causal evidence of teleworking productivity for such workers has been scant.

An interview survey at RIETI

In response to the outbreak of COVID-19, RIETI, the economic research institute where I work, is strongly urging its employees to work from home. On typical weekdays in March, about half of employees – including managers, staff, and researchers (fellows) – work from home. Exploiting this quasi-natural experiment, I conducted an interview survey in the middle of March of full-time employees and executives at RIETI about their productivity at home. Although the sample size is small, about 95% of full-time people responded to the survey.

The specific question is: “Suppose your productivity in the office to be 100, how do you evaluate your working productivity at home?” In addition, I asked for specific reasons for higher/lower productivity at home. Although the productivity measure is subjective in nature, the results obtained from the unexpected event can be interpreted as causal evidence.

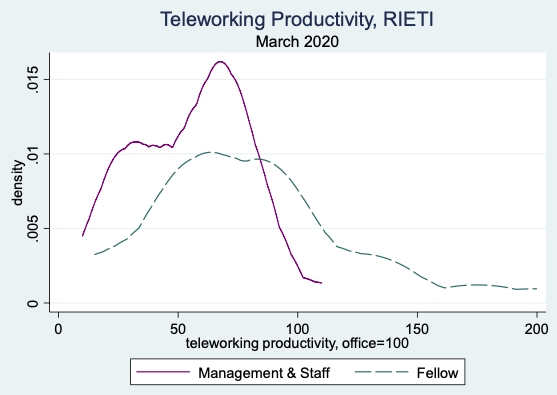

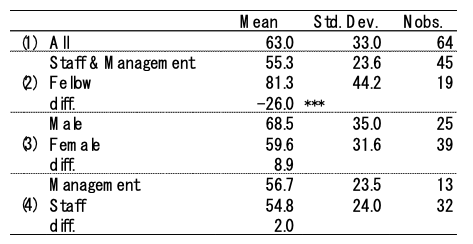

The productivity distribution of teleworking is indicated in Figure 1. The means and standard deviations by individual characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The figure depicts the productivity of managers and staff (solid line) and that of researchers (dashed line) separately. The main findings from the figure and table are as follows. First, productivity of teleworking relative to working in the office is low (63 at the mean). Second, researchers’ relative teleworking productivity (81 at the mean) is, on average, better than that of managers and staff (55 at the mean) and the difference is statistically significant at the 1% level. Third, the dispersion of productivity is very large even within the same occupation. A small number of people answered that their productivity at home is higher than in the office, but a non-negligible number of people indicate that it is lower than half when at home.

Figure 1 Distribution of productivity at home

Note: Horizontal axis indicates the subjective assessment of teleworking productivity relative to office work (=100). N=64.

Table 1 Mean and dispersion of teleworking productivity by individual characteristics

Note: The figures indicate subjective assessment of teleworking productivity relative to office work (=100). ***: p<0.01.

What determines teleworking productivity?

A natural next question is why there is such a large variation in productivity at home. Differences by gender or job-ranking are small and statistically insignificant (rows (3) and (4) of Table 1). To summarise the qualitative comments obtained from the interviews, there are four major factors affecting teleworking productivity.

First, many people stressed the lack of user friendliness of both software and hardware used to gain remote access to the office IT system. Some of this effect seems to reflect switching costs arising from different keyboards and a lack of experience in using the software. In this respect, productivity at home will be improved gradually through a learning effect, particularly for those at the lower end of the productivity distribution.

Second, some tasks must be conducted in the office (in some cases, for security reasons). Many people commented that they separated tasks conducted in the office and those at home for this reason, suggesting that full teleworking (i.e. five days a week) may substantially reduce overall productivity performance. In order to deal with this constraint, internal rules and regulations could be modified, but a trade-off between productivity and security is inevitable. Introduction of secured ICT system applicable to working from home may mitigate this trade-off to some extent.

Third, some people emphasised the loss of the valuable, quick communication that is only possible through face-to-face interactions with their colleagues, consistent with the result in Battiston et al. (2017). This reason was raised not only by managers and staff, but also by some researchers.

Fourth, a poor working environment at home – in particular, lack of a private room specifically designed for work – is a serious constraint on teleworking for many people. In addition, some people stated that it is difficult to efficiently work at home because of the presence of small children. These constraints cannot be removed in the short or medium term.

Consider these factors together, I conjecture that the productivity when teleworking is expected to converge towards productivity in the office, but the difference cannot be removed completely mainly because of the third and fourth factors above, at least on average.

Policy implications

Although there are limits to how much productivity at home can be improved, when considering the risk of COVID-19 infection from long, daily commutes and the significant possibility of transmission in office environments due to the long incubation period, the expansion of teleworking will help reduce costs to the economy and society.

The COVID-19 shock is affecting both the demand side and the supply side of the economy. Preventive measures against the spread of infection as well as speedy developments in effective therapeutic agents and vaccines will be effective for both sides. Apart from these policies that directly decrease the magnitude of the shock itself, policy measures that are effective both for demand creation and improving productivity are valuable. In this respect, subsidising firms’ or individuals’ ICT investments related to teleworking can be considered wise spending. It immediately creates a demand for ICT equipment and software ,as well as improving productivity at home.

References

Bloom, N, J Liang, J Roberts, and Z Jenny Ying (2015), “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(1): 165-218.

Battiston, D, J Blanes I Vidal, and T Kirchmaier (2017), “Is Distance Dead? Face-to-Face Communication and Productivity in Teams.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11924.

Dutcher, E G (2012), “The Effects of Telecommuting on Productivity: An Experimental Examination. The Role of Dull and Creative Tasks.”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 84(1): 55-363.

Morikawa, M (2018). “Long Commuting Time and the Benefits of Telecommuting.” RIETI Discussion Paper, 18-E-025.