Financial markets, even more than other markets, run on trust and stumble in its absence (Thakor and Merton 2018). Complete contracts accounting for all conceivable contingencies are a textbook abstraction. Adjudication by courts is time consuming and unpredictable. For transactions to be sustained, counterparties must be trusted, as emphasised by Arrow (1974). This is why, historically, one observes a concentration of commercial and financial transactions among individuals with a common cultural background who share extra-economic links, values, and trust. It is plausibly why investors, despite advances in technology leading to a proliferation of hard information, still underweight culturally distant foreign markets (Anderson et al. 2011) while overweighting firms whose CEOs share a common cultural background (Grinblatt and Keloharju 2001).

These considerations apply with special force to international investments, and to investments in the bonds of foreign sovereigns in particular. Sovereign bonds are incomplete contracts, as demonstrated by the history of default, restructuring, and repudiation. Multiple countries make for multiple courts with uncertain jurisdiction. Governments enjoy a degree of sovereign immunity, casting doubt on the existence of a judicial solution to default. Such considerations heighten reliance on trust as an alternative to legal contract enforcement. Sovereign bonds tap into these cultural stereotypes in that they are directly associated with a national government and a nationality.

A bank-level measure of trust

In a new paper (Eichengreen and Saka 2022), we use hand collected data on banks’ investments in European sovereign debt to show that trust has an economically important impact on cross-border investments. Specifically, when residents of the country or countries where a bank operates have a high level of trust in residents of another country, the bank is more likely to hold claims on that other country. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of the role of trust, rooted in cultural stereotypes, in bank lending to governments. It is also the first evidence of the transmission of such cultural stereotypes via the operation of multinational bank branch networks.

Previous studies (e.g. Guiso et al. 2006, 2009) have used aggregate survey data from Eurobarometer to show that the volume of flows between pairs of countries is importantly affected by bilateral trust. A limitation of such country-level evidence is that average levels of trust are almost certainly correlated with unobserved characteristics of country pairs. To rule out confounding factors, we therefore develop a bank-specific measure of trust.

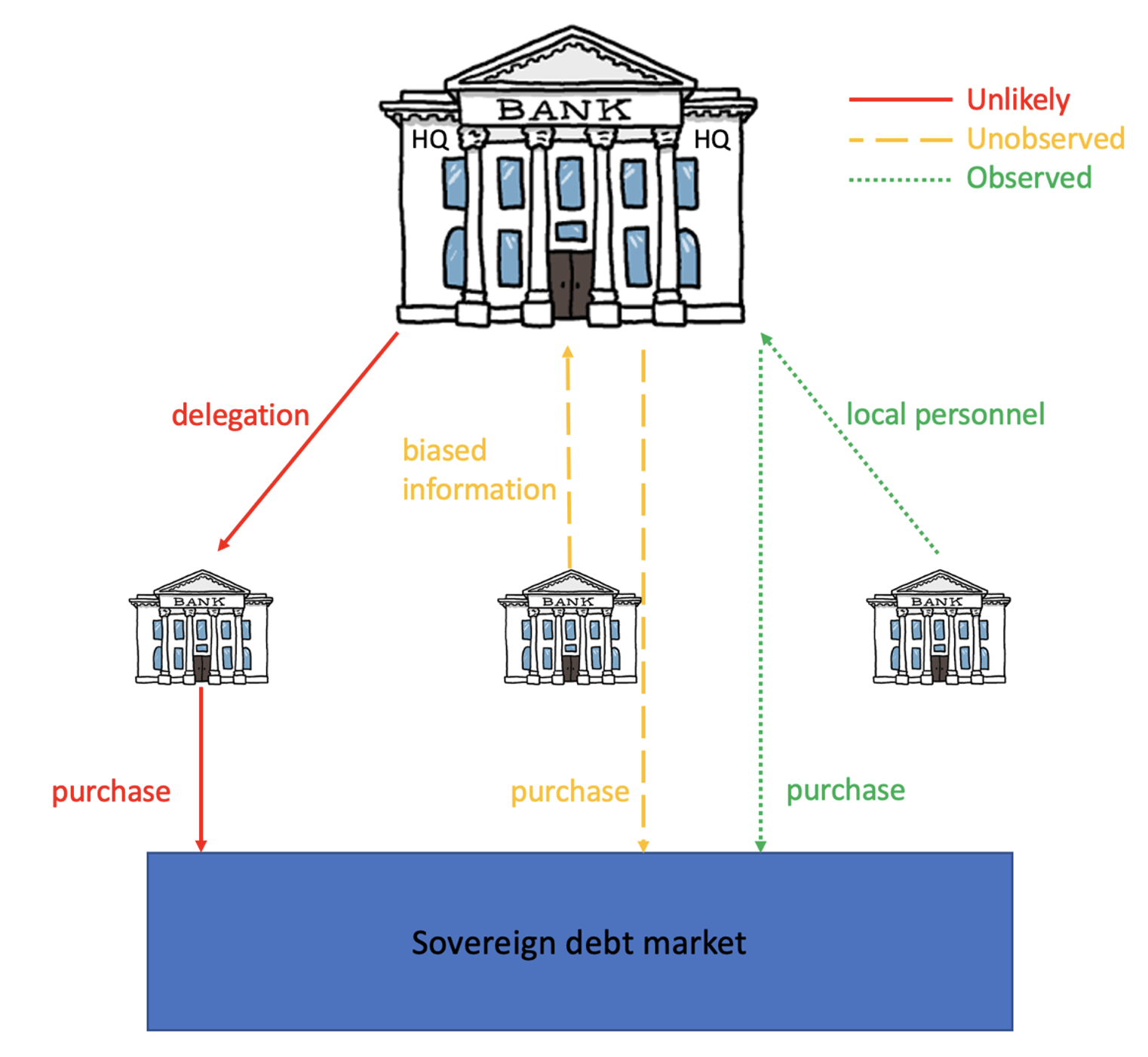

For this purpose, we model banks as hierarchies (as illustrated by Figure 1). Strategic decisions such as whether or not a bank should invest in a country are generally taken at bank headquarters. Portfolio managers working in the headquarters country or elsewhere are then responsible for implementing those decisions. Because we are concerned with investment decisions undertaken by headquarters, we focus our analysis on the extensive margin of sovereign exposures – whether or not a bank invests in the bonds of a country, as opposed to exactly how much it invests.

Figure 1 Banks as hierarchies

Notes: This figure represents the mechanisms that link foreign bank branches to multinational banks’ sovereign exposures in Eichengreen and Saka (2022).

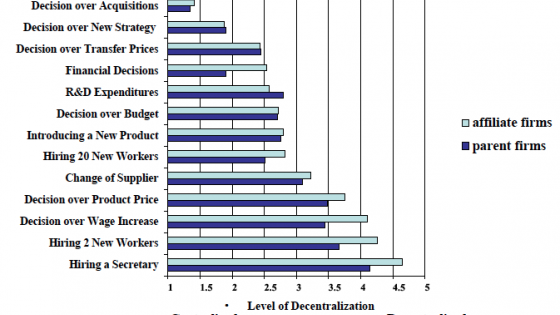

Given this framework, cultural stereotypes in subsidiaries can shape the soft information that subordinates transmit up the hierarchy to headquarters, where the broad parameters guiding portfolio investment decisions are set. They can affect how that soft information is received by directors, because the latter share the same stereotypes, reflecting the extent to which banks hire and promote internally across borders, such that the composition of bank boards and officers reflects the geography of the bank’s branch network. We provide empirical support for this framework by showing that multinational branch networks help predict the national composition of high-level managerial teams at bank headquarters.

Our central analysis focuses on banks with branches in multiple countries. We assign to branches of a bank operating in a country that country’s level of bilateral trust in other countries. We aggregate this measure by calculating a weighted average, where weights are the share of host-country branches in the network of the bank. We repeat this for each target country of potential investment, across which a bank’s bilateral trust differs. Our measure of trust is therefore specific to both the bank and the target country of potential investment.

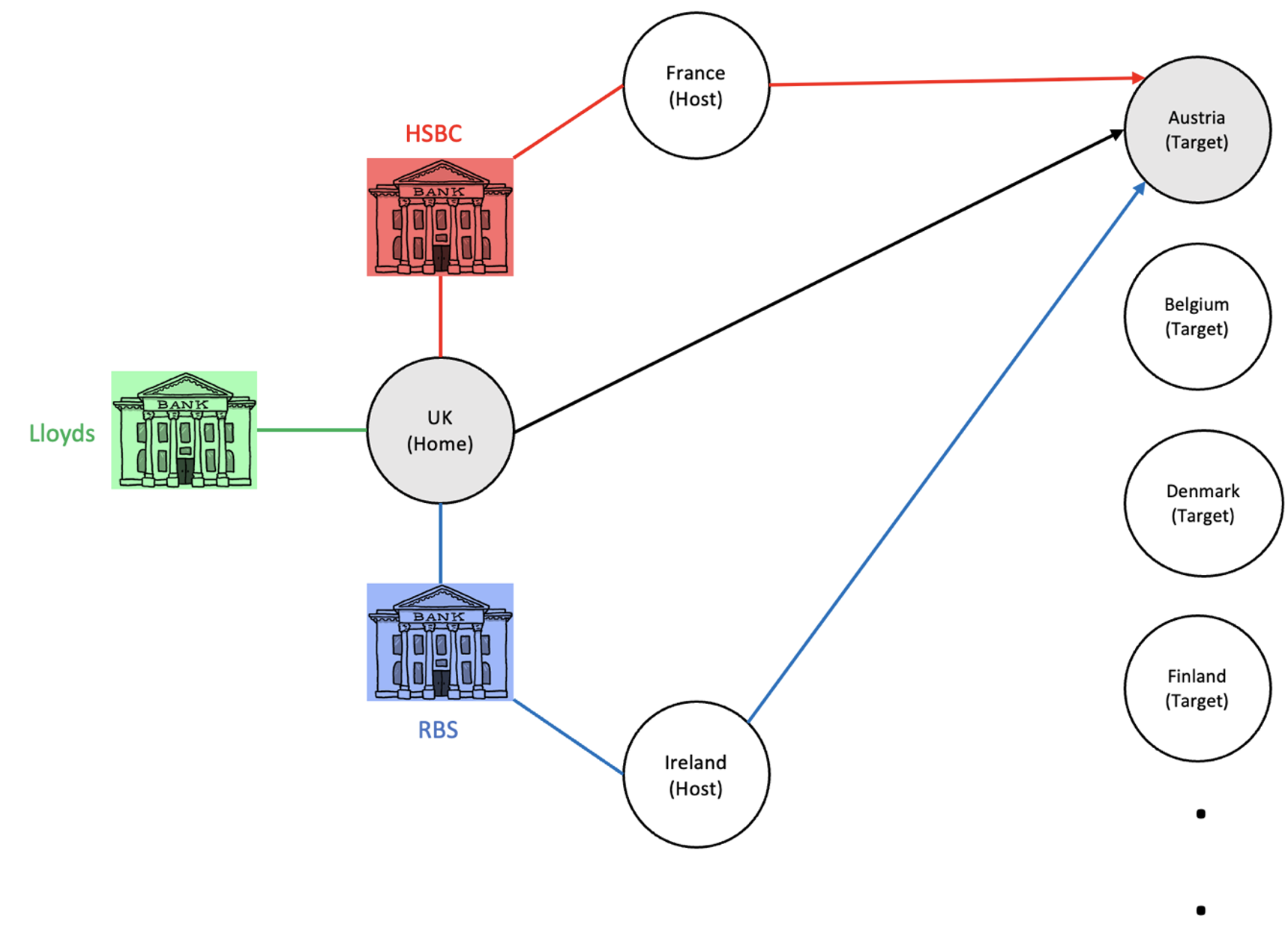

Leveraging this banks-as-hierarchies approach and focusing on multinational banks has advantages from the point of view of identification. Trust in a target country can differ across multinational banks headquartered in the same country insofar as they have branches in different foreign countries or in the same foreign countries but with different weights (see Figure 2 for an illustration). By focusing on this within-country-pair variation, we can rule out other omitted factors at the country-pair level. We can do so even when latent influences are time-varying, since our strictest specification includes country-pair * time dummies, along with bank * time and target-country * time fixed effects. We consequently compare banks headquartered in the same country with respect to the same target country at the same point in time, thereby ruling out all country-level confounding factors.

Figure 2 Identification strategy at bank level

Notes: This figure represents the identification strategy as described in Section 4 of Eichengreen and Saka (2022).

The persistence of cultural stereotypes

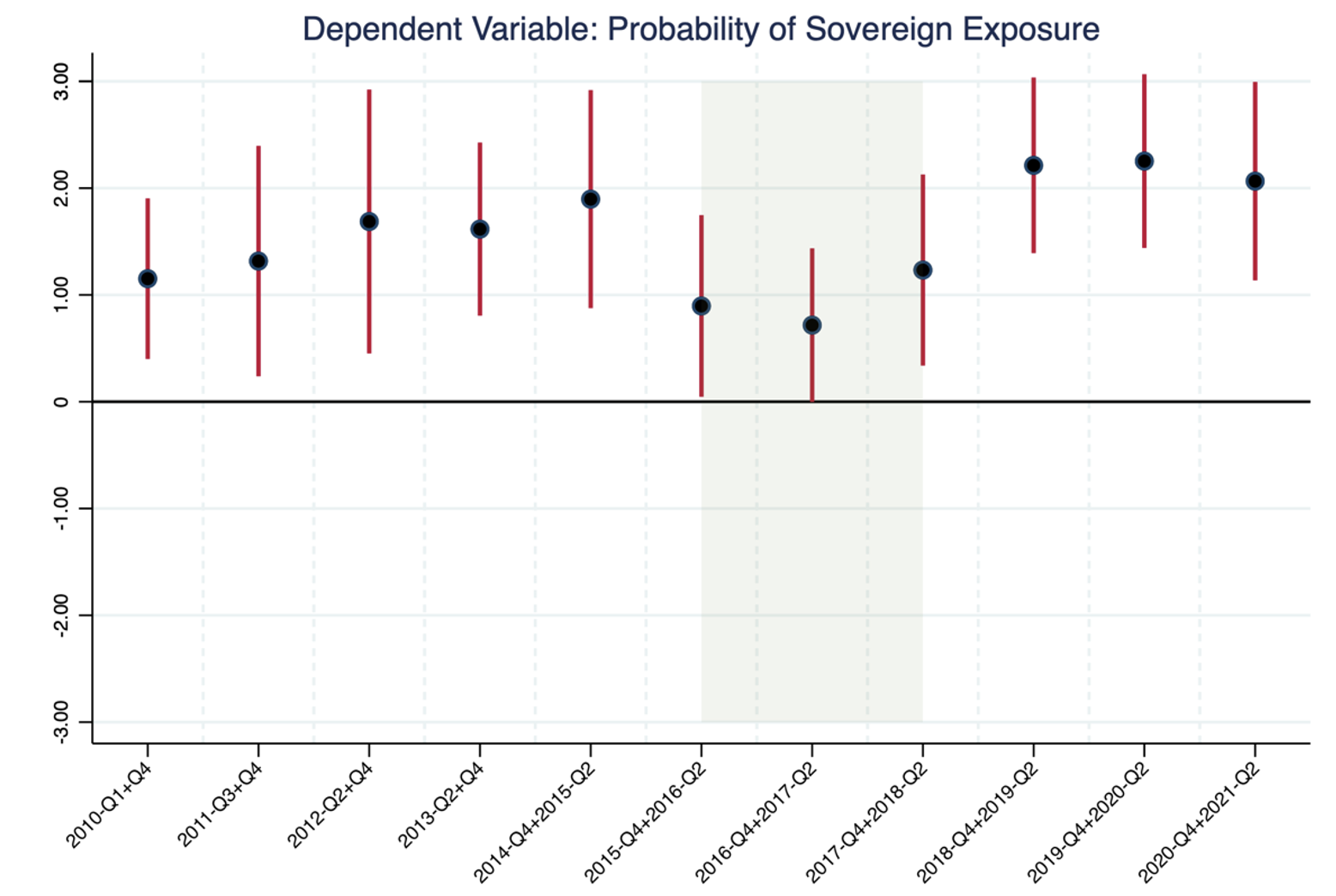

We show that our bank-level measure of trust predicts banks’ entry/exit decisions vis-a-vis sovereign debt of a country. A one standard deviation rise in bank-level trust bias increases the probability of investing in a target country by 14%. This is a large effect, accounting for one-third of the diversification gap (i.e. 42%) in banks’ sovereign exposures. Figure 3 shows that the effect is stable over a sample period spanning more than a decade. It is not only statistically significant and economically important but also persistent over time.

Figure 3 The impact of bank-level trust bias over sub-sample periods

Notes: This figure shows estimates for the coefficient of bank-level trust bias separately for 11 distinct sub-sample periods. Dependent variable is a dummy indicating any positive exposure of a bank toward a target country at a point in time. Shaded areas indicate sub-periods during which EBA reported sovereign exposures based on regulatory FINREP data that restrict the level of granularity disclosed in banks’ sovereign debt portfolios. The specification is Column 5 of Table 3 in Eichengreen and Saka (2022). Only the estimated coefficient on Bank-level Trust Bias is plotted. Confidence intervals are at 90% significance level. Source: EBA, CEBS, Eurobarometer, and SNL Financial.

We show further that well diversified, relatively sophisticated banks are less likely to lean on trust as a determinant of their sovereign lending. Moreover, investments in target countries whose bonds are not frequently found in bank portfolios, about which hard information may be relatively scant, are more likely to be influenced by cultural stereotypes. Finally, we find that the impact of trust is substantially higher for target countries experiencing a sovereign debt crisis, when cultural stereotypes – and thus the role of trust – may become particularly salient.

Our findings remain intact for alternative definitions of trust. They are not driven by domestic exposures, exchange rate fluctuations, observations for relatively weak target countries (in our setting Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain), or banks headquartered there. By flexibly controlling for the extent of branch penetration in the target country, we show that cultural stereotypes based on the geography of bank branches are not picking up the information-gathering role of branches. By controlling for a weighted-average set of characteristics at bank/target-country level, we rule out the possibility that our bank-level measure of trust is picking up other types of indirect financial, informational, or political linkages that may be operating via host countries. Finally, using data from the European Central Bank’s Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), we show that our results are not driven by the heterogeneity in local supervision of these banks.

Conclusion

Our findings have important implications for interpreting financial allocations. Because we are comparing banks from the same home country facing the same target country at the same point in time, and because we are focusing on the sovereign debt markets where lender-borrower interactions are not relational and default tends to be across the board, trust differentials lead to inefficiency in our setting. Since trust-induced changes in portfolio decisions have nothing to do with the fundamental risk of the target country but simply reflect cultural stereotypes, they are likely to represent divergences from optimal portfolio allocations.

Our results also have implications for how multilateral banks should think about the design of high-level managerial teams responsible for their cross-country investments. In particular, banks with branch networks that are geographically well-diversified and whose management teams similarly are geographically well-diversified are less likely to suffer from such biases. For a bank with a well-diversified branch network, the biases transmitted by different national branches cancel out and hence tend to zero overall. If cultural biases matter, diversity in bank management brings in a more balanced view of the potential investments and consequently more efficient portfolio allocation.

References

Anderson, C, M Fedenia, M Hirschey and H Skiba (2011), “Cultural Influences on Home Bias and International Diversification by Institutional Investors”, Journal of Banking and Finance 35: 916-934.

Arrow, K (1974), The Limits of Organization, New York: Norton & Co.

Eichengreen, B and O Saka (2022), “Cultural Stereotypes of Multinational Banks”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP17754.

Grinblatt, M and M Keloharju (2001), “How Distance, Language, and Culture Influence Stockholdings and Trades”, Journal of Finance 56: 1053-1073.

Guiso, L, P Sapienza and L Zingales (2006), “Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 20: 23-48.

Guiso, L, P Sapienza and L Zingales (2009), “Cultural Biases in Economic Exchange”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124: 1095-1131.

Thakor, R and R Merton (2018), “The Implications of Trust on the Lending Activities of Banks and Fintech Firms”, VoxEU.org, 21 August.