Before the recent anniversary of the Dayton Peace Accords signed in Paris 14 December 1995, Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt expressed regret that Bosnia and Herzegovina had accomplished so little in the intervening 15 years. He compared Bosnia’s achievements with those of West Germany in the 15 years prior to 1960 and suggested that this comparison should give the Balkan state’s newly elected politicians cause for serious reflection.

Fifteen years ago, the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina ended with a peace treaty imposed by outsiders on the aggressor. War-time political leaders were still in power and had elevated ethnic enmities to national animosities, making Dayton appear more like a cease-fire than a peace treaty. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the pent-up conflicts that had torn the Yugoslav Federation apart remained unresolved, indeed concentrated, after the war. One consequence of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s “frozen conflict” is that, of the Balkan countries, Bosnia and Herzegovina has made the least progress both in terms of integration into European trade flows and in terms of economic recovery.The two are interdependent.

Bosnia and Herzegovina lags behind most other Balkan countries as reflected in its track record in fulfilling its obligations under the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), in its Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU, and in terms of potential candidacy for EU membership (Gylfason and Wijkman 2011). In its latest assessment of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Commission document appears to be at a loss for synonyms to describe the little progress made by Bosnia and Herzegovina on key SAA issues. Bosnia and Herzegovina may require five more years to implement the SAA fully.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the few Balkan states not to have submitted an application for EU membership. To do this it must first accede to the WTO, revise its Constitution, and abolish the Office of the High Representative. This may take five years or more. Accession to the WTO is a time-consuming process. The Constitution enacted by the Dayton Accords was designed to prevent any of three ethnic groups from dominating, or being dominated by, the others. It created several, often competing levels of government (State, Entity, District, and Cantonal), a tripartite Presidency (requiring a consensus between the three ethnic groups), and finally a Parliament with two Chambers (with built-in ethnic vetoes). Since Bosnia and Herzegovina politicians lack a shared vision for the country, these different levels of government have resulted in political deadlocks that prevent enactment of necessary legislation. For instance, the SAA calls for setting up a national state aid agency, but politicians cannot agree on which level to set it up. A study by the World Bank in 1997 predicted that fiscal federalism of Dayton would render decision-making inefficient if the ethnic groups lacked sufficiently common interests (Fox and Wallich 1997). This has now proved to be the case. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s public sector has Europe’s third largest share of employment (after France and Belgium), and dictates wages that have eroded competitiveness of the private sector (IMF 2010).

The Office of the High Representative, created by the international community and empowered to veto laws, reflects foreign distrust of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s ability to govern itself in an initial phase. After 15 years Bosnia and Herzegovina has been unable to fulfil the conditions for abolishing the Office of the High Representative. Prolonged foreign tutelage is conducive to dependency and irresponsibility.

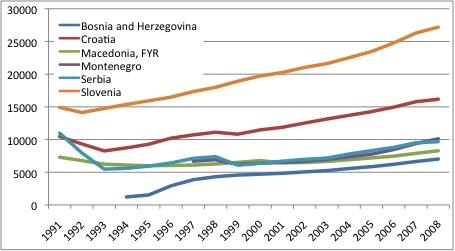

Frequent political deadlocks have stunted per capita income growth in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although pre-war statistics are uncertain, per capita GDP fell sharply during the war 1992-1995, and remains below its neighbours. Bosnia and Herzegovina is heavily dependent on remittances from abroad. Few refugees have returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina and foreign direct investment is low. By contrast, after the Second World War, per capita GDP in the major belligerents in Western Europe had returned to pre-war levels after five years (Baldwin and Wyplosz 2006). Other Balkan countries continue to show modest growth, especially Serbia and Montenegro where the Kosovo war had long-lasting consequences. Only Croatia, which opened EU membership negotiations in 2005, recovered quickly and continues to grow rapidly. Slovenia, an EU member from 2004, recovered quickly.

Figure 1. GDP per capita 1991-2008 (PPP, constant 2005 international $)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2010.

Is breakup imminent?

If the vicious circle of economic stagnation and political deadlock continues, it is likely to lead to a breakup of Bosnia and Herzegovina. To remain a viable state, a process of reconciliation between Croats, Serbs, and Bosnians is essential. But only in the last year or so have political leaders made statements signalling the possible initiation of such a process. Representatives of Republika Srpska continue to express a wish to break out of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The prospect that the centre will not hold and the confederation fall apart will prolong economic stagnation by discouraging both foreign and domestic trade and investments. Dayton was intended to prevent a breakup of Bosnia and Herzegovina into ethnically homogenous states involving massive population exchanges. But it may lead to precisely that outcome through the current constitution if Bosnia and Herzegovina is unable to eliminate the elements of ethnic discrimination which it contains.

If Bosnia and Herzegovina breaks up, its possible successor states are unlikely to qualify for membership in the EU. After the genocide committed at Srebrenica, the brutal siege of Sarajevo, and a breakup of Bosnia and Herzegovina, bloody or not, several EU member states would oppose the entry of Republika Srpska whether as a single entity or as a part of Serbia. Because of EU member states’ own bitter history, the principle of human and minority rights cannot be compromised. Bosnia and Herzegovina may do well to recall the problems Turkey faces in acceding to the EU (Gylfason and Wijkman 2010). The expulsion of up to 1.4 million Greeks (albeit formally a ‘population exchange’) and the fate of up to 1.5 million Armenians during the Ottoman Empire, cast their shadows 90 years later.

Condemned to stay together?

Can Bosnia and Herzegovina stay together and transform into a viable state with a vision of a common future? Perhaps if the entities cease to believe they have another option. Croatia and Serbia as part of their accession process must solemnly declare to the EU that they respect the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina and will abstain from interfering in its internal affairs. Deprived of the prospect of outside support, the entities in Bosnia and Herzegovina may finally revise the Constitution to provide for more effective decision making and remove the ethnic discrimination that is incompatible with EU principles. While necessary, this is far from sufficient to become a candidate country.

The EU and the US must also use their considerable soft and hard power to ensure that the parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina resolve their differences. The EU has to convince all parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina that membership is only possible subject to specific political conditions and establish an agreed road map and timetable for fulfilment of these conditions. The soft power of the prospect of membership (“European perspective”) has worked for some countries with internal conflicts, such as the Baltic countries. But resolving Bosnia and Herzegovina’s more serious internal conflicts will require the use of hard power as well. Nothing less than a major programme of financial assistance for economic reconstruction and return of refugees may be necessary.

The peace and prosperity of the EU today stem from Western Europe having embarked on a course of economic and political integration 65 years ago. It has learnt that diversity enriches community and that community must also protect diversity. Restoration of the once rich diversity of Bosnia and Herzegovina is a quintessentially European task. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s population ultimately needs EU institutions to guarantee its human rights and minority rights. This is likely to be true of several countries in the Eastern Partnership, such as Moldova, with far-reaching implications concerning the scope of hard power and supra-national enforcement of legal commitments.

References

Baldwin, Richard, and Charles Wyplosz (2006), The Economics of European Integration, McGraw-Hill.

Bildt, Carl (2010), “Femton år efter Dayton”, 21 November.

European Commission (2010), Bosnia and Herzegovina 2010 Progress Report, SEC (2010) 1331.

Fox, William, and Christine Wallich (1997), “Fiscal Federalism in Bosnia-Herzegovina: The Dayton Challenge”, World Bank Report No. 1714.

Gylfason, Thorvaldur, and Eduard Hochreiter (2008), “Governance and growth: Why does Georgia lag behind Estonia?”, VoxEU.org, 2 August.

Gylfason, Thorvaldur, and Eduard Hochreiter (2010), “Growing together: Croatia and Latvia”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Gylfason, Thorvaldur, and Per Wijkman (2010), “Turkey’s road to Europe”, VoxEU.org, 24 April.

Gylfason, Thorvaldur, and Per Wijkman (2011), “Economic integration as a Balkan peace project”, VoxEU.org, 1 January.

IMF (2010), “Bosnia and Herzegovina: Selected Issues”, November, IMF Country Report No. 10/347.

Wijkman, Per Magnus (2009), “Frihandel för fred: Exemplet Balkan (Free Trade for Peace: The Balkan Example)”, SNS Förlag, Stockholm.