We are living through a health crisis that ranks among the worst since the Black Death in terms of its human toll and its economic disruption. The consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic have been mitigated by unprecedented policy responses (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020). On the public health front, rapid interventions and vaccines are being applied at scale. And monetary easing (English et al. 2021), fiscal support (Deb et al. 2022), and debt accumulation have all served as a cushion on the economic side.

The 24th Geneva Report on the World Economy looks at the state of debt in the world today and what it portends (Boone et al. 2022). Debt and credit are closely linked to financial crises, to the evolution and shape of the business cycle, and to the likelihood of negative tail events. Financial vulnerability is endemic in a highly leveraged world. In a time of such record-high debt, it is difficult not to be pessimistic about our future economic, financial, social, and political stability. One might even conclude that debt needs to be urgently reduced.

Download Debt: The Eye of the Storm, the 24th Geneva Report on the World Economy, here.

After a new surge in borrowing during the pandemic, everything still looks quite calm almost two years later. Is debt just the eye of the storm? Will the smooth absorption of unprecedented debt issuance endure, or will the strain of this global shock eventually make its presence felt here too? Where are the weak spots? Our report has several major themes and, while noting areas of concern as well as massive uncertainties, we conclude that there are also reasons to be optimistic.

Taking a longer view, debt was already elevated before the pandemic. Public and private sector debt in advanced and emerging market economies had surged to unprecedented highs in the past four decades, before rising further in the pandemic. However, that long-term trend played out against a backdrop of abundant funding from three main sources – the savings gluts of the old, the rich, and the rest of the world – and a context of weak investment.

The drop in real interest rates in both advanced and emerging market economies at a time when debt was surging suggests that the urge of creditors to save has far outpaced any shifts in borrowers’ desire to issue more debt. Our view is that a low real natural rate, r*, is a structural feature of the global macroeconomy – one largely beyond the control of policymakers and one that it is likely here to stay for a considerable time as the underlying forces pushing the world into saving more remain intact.

Public debt

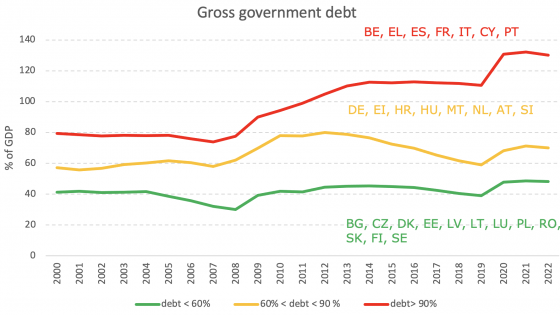

Public debt in advanced economies has surged due to the pandemic, but borrowing costs are close to an all-time low and lower than growth rates (r < g). Central banks have also helped funding conditions in the short run. While there are plenty of challenges for fiscal policy in the coming years (e.g. ageing, inequality, digitalisation, the green transition), the situation in advanced economies appears manageable for now.

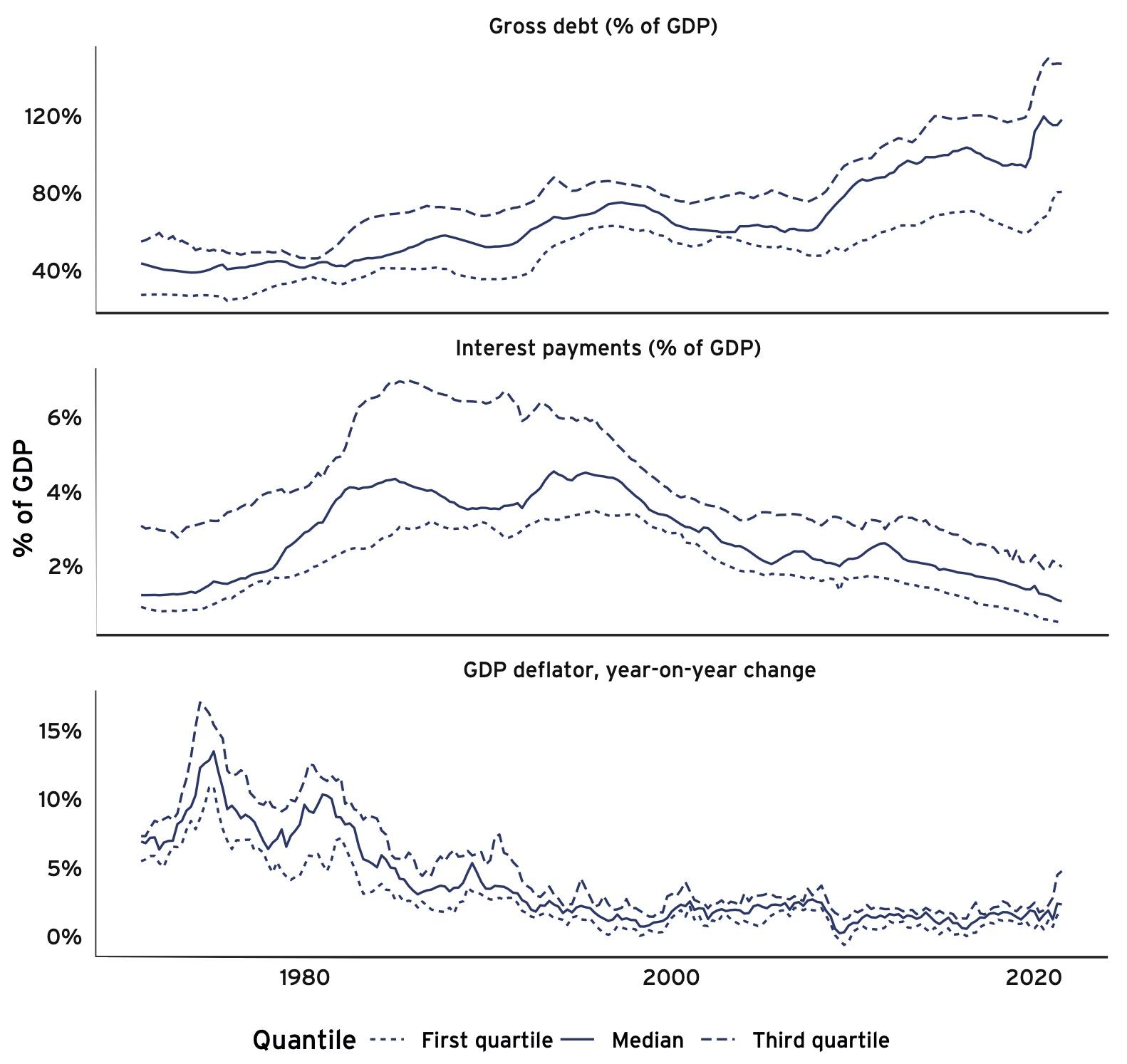

This state of affairs is illustrated in Figure 1 for 15 OECD economies. The top panel in the figure shows the rapid run-up in public debt in the past 40 years, from about 40% of GDP in the early 1980s to over 100% today. However, debt burdens today are about the same as debt burdens in the 1980s, as the second panel in the figure shows.

Of course, one of the salient features of the world economy at the time of writing this column is the quick pickup in inflation seen in nearly all advanced economies. Is higher public debt to blame? The third panel of Figure 1 would suggest that this might be too premature a conclusion. At a time when public debt has more than doubled since the 1980s, inflation has declined from a high of about 12% to about 3% right before the latest pickup in inflation.

Beyond the transitory nature of Covid-related supply disruptions and their effect on inflation, three narratives have emerged arguing that inflation may not wane after the pandemic comes under control. The first narrative, based on the traditional Phillips curve concept, emphasises the potential for large fiscal stimulus programmes – especially in the US – to cause an overheating of goods and/or labour markets. A second narrative ascribes an important role to monetary factors in conjunction with government debt dynamics. A third narrative, based on the fiscal theory of the price level, postulates a more direct link between unsustainable and ‘irresponsible’ fiscal policies and inflation.

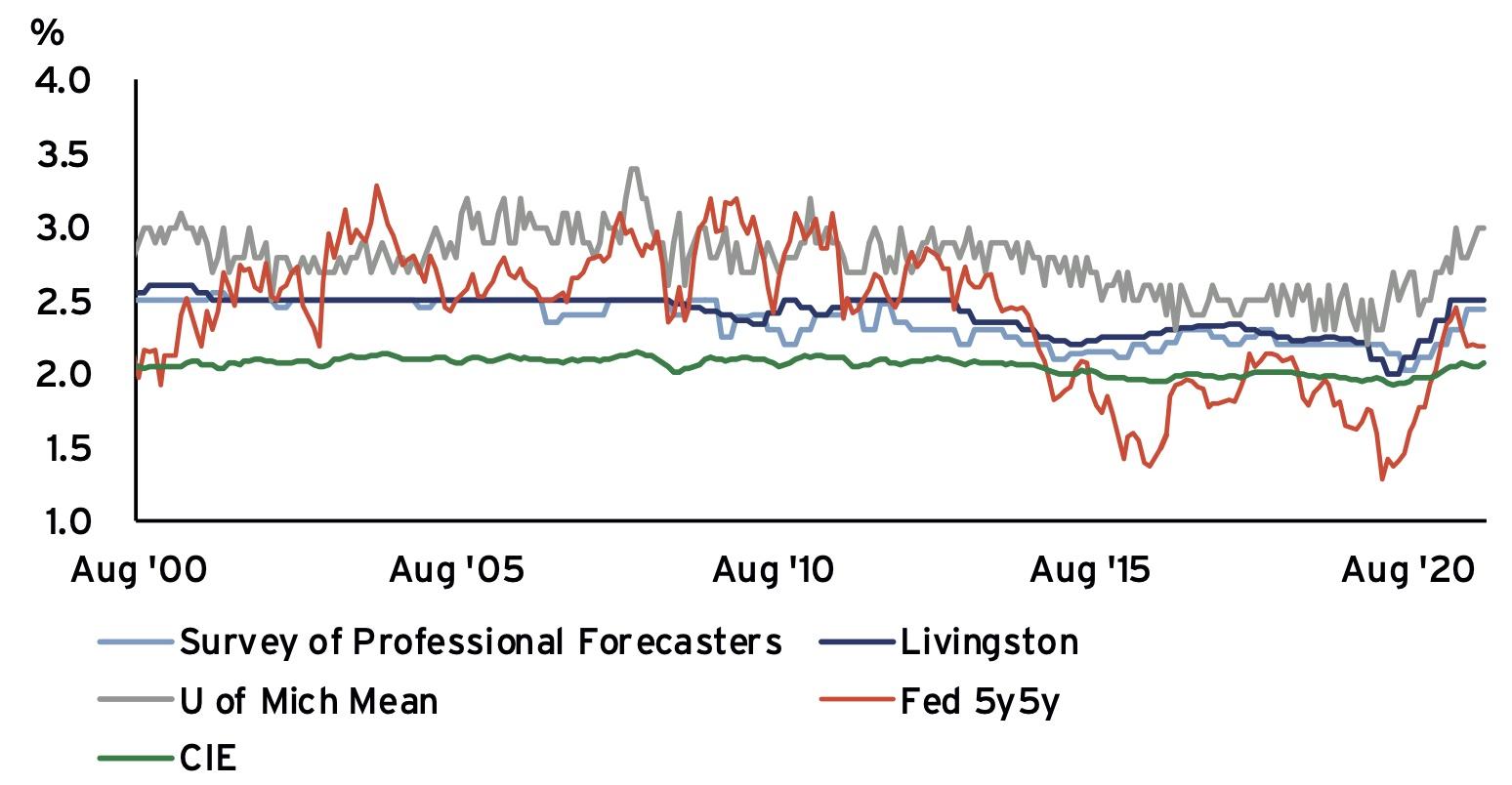

At this juncture, the peak fiscal response is behind us. Going forward, most governments are already planning on bringing their finances back in check. Second, central banks are either telegraphing or already adopting a more hawkish stance to monetary policy. Finally, in an environment where r < g, governments enjoy greater credibility that they can bring finances back in check before they become unsustainable. It is perhaps for these reasons that measures of long-term inflation expectations have remained relatively well anchored in the face of surging public debt, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 1 Long term evolution of public debt, government interest payments and inflation in 15 OECD countries

Figure 2 Long-term inflation expectations remain well anchored

Household debt

Household debt in advanced economies, which played a central role in the global financial crisis, declined post-crisis and has not increased significantly in the pandemic. The combination of a low interest rates and household deleveraging that followed the global financial crisis have led to a significant decline of debt burdens in advanced economies. While house prices are surging, this is not a credit-fuelled boom and thus is unlikely to be a major source of systemic risk in the immediate future.

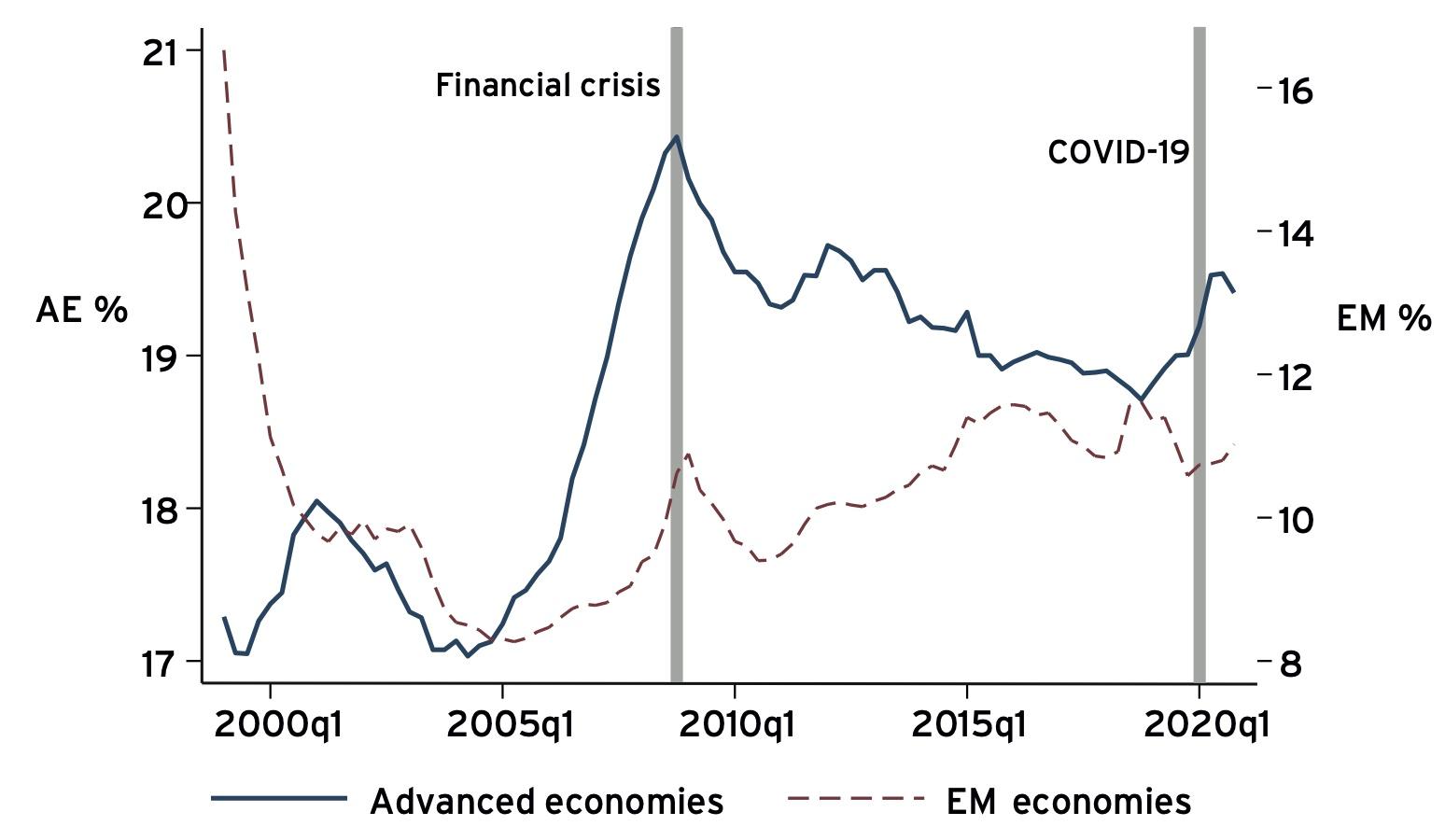

In contrast, debt burdens increased in emerging economies the lead up to the pandemic, though overall debt burden levels are about half of those in advanced economies, as shown in Figure 3. Household debt in emerging market economies now stands at levels seen in advanced economies in the early 2000s. This bears watching as household debt booms predict financial crises and recessions that are deeper and longer.

Figure 3 Debt burdens relative to disposable income are manageable

Corporate debt

Over the past 70 years, debt of non-financial corporations has doubled from around 50% of GDP to over 100%, with most of the increase taking place since the global financial crisis. In the past ten years, corporate debt has increased by 60% in advanced economies relative to its level in 2008, but only about 20% in emerging economies. Corporate debt is an area to watch, but fears about zombification – the evergreening of corporate debt unlikely to be repaid by essentially failed businesses – and its adverse effects on the macroeconomy depend critically on smooth bankruptcy and resolution procedures.

Overall, we conclude that worries about the debt position of the corporate sector are probably overblown. Clearly, in light of the run-up in corporate debt, there will be pockets of default and creditor losses; not all leveraged loan deals will go well. However, we have tools to deal with over-indebted corporations in the form of bankruptcy laws and debt-reorganisation institutions. When such institutions are well set-up and left to function smoothly, corporate debt booms typically leave few traces on the macroeconomy.

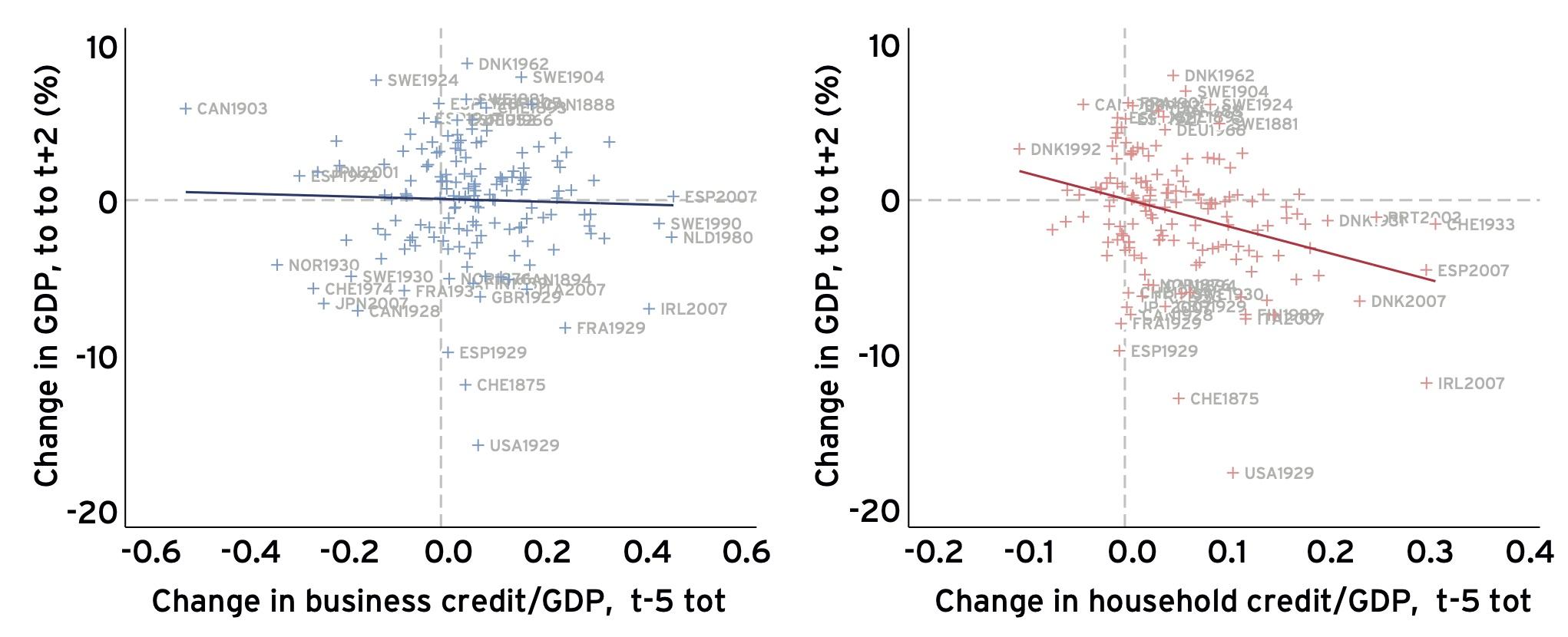

This stands in sharp contrast to household debt booms. This is illustrated in Figure 4. The left panel of the figure displays a scatter plot of the change in business credit in the five years leading to a recession against the change in GDP in the two-year recession interval (recessions tend to last between one and two years, generally). As the panel shows, there is essentially no relationship. Contrast this to the right-hand panel of the figure, which instead relates household debt and the path of the recession, where a relationship can be clearly seen.

Figure 4 Corporate versus household debt booms and the severity of the recession

China’s debt surge: How concerned should we be?

China’s debt levels have soared since the global financial crisis, with the total (government, corporate and household) debt-to-GDP ratio reaching 290% in 2020, twice the 2008 level. China’s overall debt ratio is thus comparable to that of high-income advanced economies like the US (296%) and the euro area (292%) and far exceeds debt levels in other major emerging market economies such as India (181%), Brazil (189%), Russia (136.9%), and Indonesia (80%).

Both the pace of the increase and the level have been a concern for many international observers, but also within China. In the past decade, China has witnessed a credit boom of historical proportions. It has come to an end. At the time of writing our report, China’s property boom market has turned to bust, snaring several of the largest real estate developers in its wake, including China Evergrande Group, Kasia Group, and China Fortune Land – three of the largest developers in the world. Financial risks in the Chinese financial sector are therefore high. Both corporates and households have leveraged up substantially in the past decade and the housing boom appears to be turning into a housing bust.

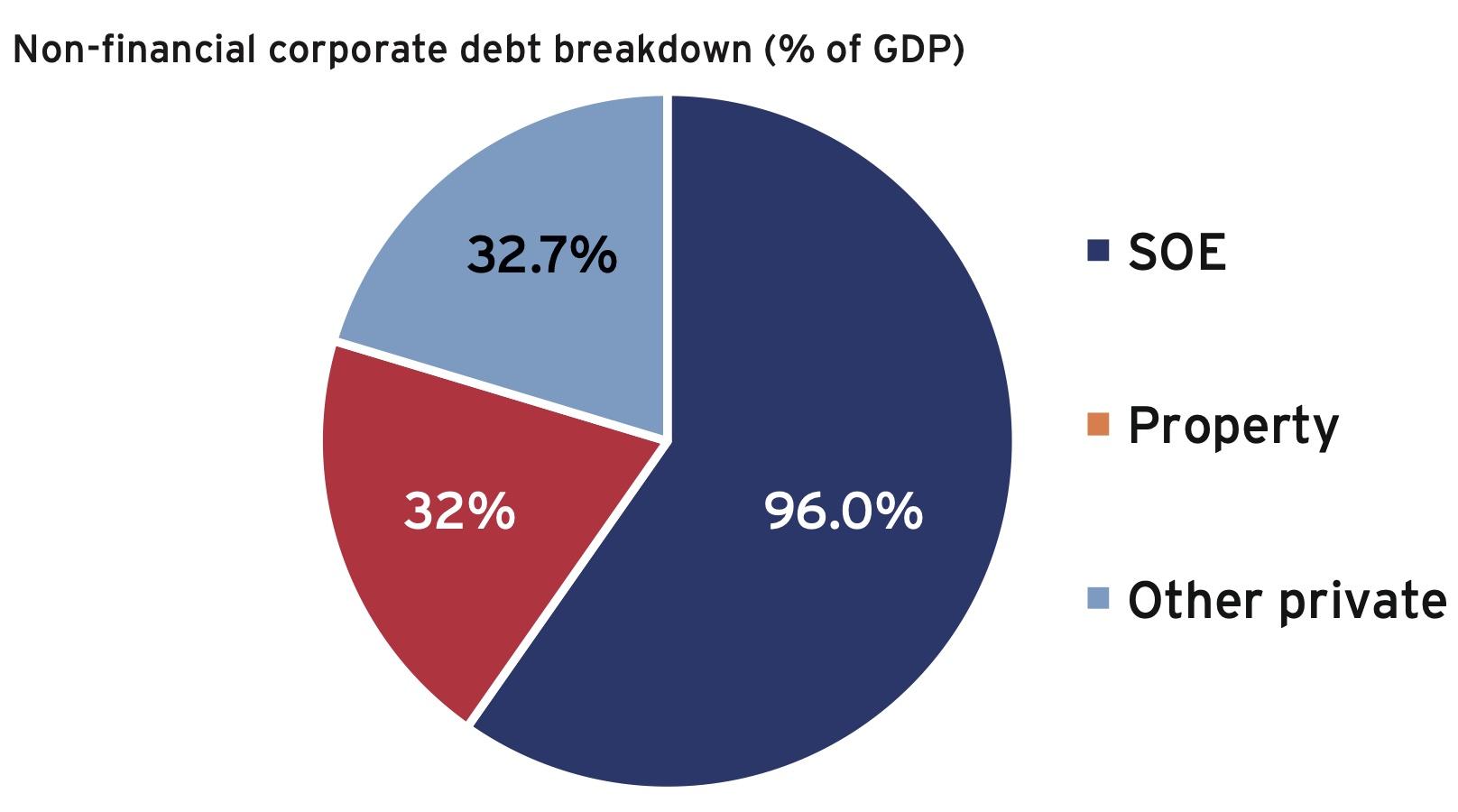

Will China experience a domestic version of the global financial crisis? There are several reasons to expect this not to be the case. First, the overwhelming part of China’s debt is held by domestic creditors. Second, for Chinese domestic investors, there is almost no way out because the capital account remains relatively closed. Third, much of the debt resides within the (broadly defined) public sector. Estimates suggest that about 60% of the corporate debt is owed by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Figure 5). With overall corporate debt (SOEs and privately owned companies) amounting to 160% of GDP, SOE debt is thus close to 100% of GDP. In addition, central government and local government debt together account for close to 70% of GDP.

Figure 5 State-owned enterprises account for 60% of corporate debt

China’s relatively high overall debt level certainly bears close watching. Recent financial stress might prove temporary if the government intervenes to organise an orderly restructuring of real-estate sector debt. However, the potential growth headwinds in the aftermath of a credit-fuelled property boom might well last longer and take time to work out. While an uncontrolled financial crisis does not seem particularly likely to us, the challenges for Chinese policymakers have grown substantially in recent months.

Conclusion

At the time of writing our report, the debt levels of households, companies, and sovereigns are at historical highs (relative to output). As alarming as this sounds, a deeper understanding of the secular causes that got us here is needed. This huge debt boom is, mechanically, the flip side of the surge in gross savings and the multiplication of financial wealth experienced in recent decades. If we look at the asset side of balance sheets, we find that, relative to their income, households have never been wealthier. In light of this wealth boom, researchers are baffled as to why households are not consuming more. Perspective thus matters in understanding why societies are accumulating – that is, both issuing and acquiring – debt in all its forms at such high rates.

The picture that the 24th Geneva Report on the World Economy paints is not one of doom and gloom. As long as credit supply remains plentiful relative to debt issuance, and thus interest rates remain low, higher levels of debt appear sustainable. As the interest cycle is turning, the largest risks are concentrated in emerging economies where households and corporates have leveraged up substantially. China’s transition from financial boom to bust is a particular risk factor. We are not blind to the challenges policymakers will have to face. Nor are we blind to the possibility, in a world awash with debt, that negative shocks will generate more bouts of instability, which will inevitably spill over onto innocent bystanders in a globalised economy. However, the trends behind the oversupply of credit will likely continue for a long time. Debt should not be ignored. But neither should it be feared.

References

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (eds) (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, CEPR Press.

Boone, L, J Fels, Ò Jorda, M Schularick and A M Taylor (2022), Debt: The Eye of the Storm, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 24, ICMB and CEPR.

Deb, P, D Furceri, J D Ostry, N Tawk and N Yang (2022), “The effects of fiscal measures during COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 2 February.

English, B, K Forbes and A Ubide (eds) (2021), Monetary Policy and Central Banking in the Covid Era, CEPR Press.