Many commentators have referred to the last few decades as the ‘second era of globalisation’ and written at length about the consequences of these developments. However, we do not yet have a thorough understanding of the causes of increased worldwide trade. Influential work by Baier and Bergstrand (2001) studied changes in the volume of trade from the 1950s to the 1980s, finding a primary role for income growth in the rise of trade. In new research, we complement this work by using confidential data on firm exports from the US Census to shed light on the reasons for increased firm entry into foreign markets since the 1980s (Lincoln and McCallum 2018). Using structural estimations, we show that foreign market entry costs have remained stable over time. We then use a decomposition methodology borrowed from the labour economics literature to argue that telecommunications advances, free trade agreements, and foreign market growth were vital drivers of the globalization of US firms.

Our results are consistent with claims made in the public debate that the world is becoming ‘flatter’ (e.g. Cairncross 1997, Friedman 2005) as well as results in the academic literature that the internet helps facilitate international exchange (e.g. Freund and Weinhold 2004). While we find evidence of important roles for trade agreements and structural change in foreign countries, we also find large increases in exporting by US firms to countries that experienced neither, such as Germany and UK, in contrast to the influential results of Kehoe and Ruhl (2013).

New facts

To first get a sense of why US firms began selling abroad in much greater numbers, we document a set of new facts about the US experience. Here, as throughout much of the paper, we complement plant-level analyses using the Annual Survey of Manufacturers (ASM) with firm-level estimations using the Longitudinal Firm Trade Transactions Database (LFTTD) that was originally built from US Customs records by Bernard et al. (2009). Each of these data sets has its own advantages and disadvantages. While the ASM has a rich set of plant characteristics and export data beginning in 1987, it does not record the source country of foreign revenues. The LFTTD begins in 1992 and has a more limited set of firm characteristics but contains a wealth of information about where US firms sell their products.

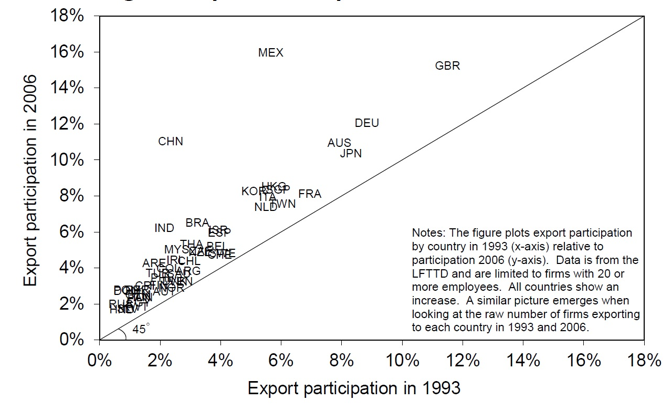

The most striking feature of the data over this time period is the pervasiveness of foreign market entry. We find increases in exporting to each of the top 50 US export destinations as well as across industries, regions of the US, and firm/plant size categories. These patterns are evident looking either at the percentage or the raw number of firms that export.

At the same time, exporting to some countries increased more than to others. In Figure 1 we plot the percentage of firms with 20 or more employees that exported to each country in 1993 and 2006. While each market saw an increase in participation, Mexico, China, India, Brazil and South Korea saw the largest increases, respectively. Given that NAFTA was signed and China and India both experienced dramatic economic growth during our sample period, it is perhaps not surprising that these countries played major roles in the globalization of US firms. We in particular find a sharp rise in exporting to Mexico just after NAFTA was signed. The UK and Germany were also among the top 10 countries that contributed to these trends.

Figure 1 Export participation across countries

Barriers to entry

While much has been written on understanding changes in variable costs to trade over time, such as shifts in tariffs and transportation costs, no analysis of how barriers to entry in foreign markets have changed has been done. This is somewhat surprising, as in any heterogeneous firms trade model along the lines of Melitz (2003), one of the most natural explanations for increased foreign market entry is that the upfront costs of entering a market abroad declined. Indeed, in a short footnote, Melitz (2003) offers this as a potential explanation for why other countries have also seen large scale foreign market entry.

The challenge to such an analysis is that direct data on entry costs are not readily available. To see how barriers to entry have changed, we build upon work by Roberts and Tybout (1997), Bernard and Jensen (2004), and Das et al. (2007), which in turn built on the seminal work of Baldwin and Krugman (1989) and Dixit (1989). This approach finds little change in barriers to entry for manufacturers as a whole across a wide range of specifications at both the plant and firm level. This is then complemented by a set of structural Monte Carlo Markov Chain estimations for three particular industries that yield similar conclusions.

Decomposing export participation

Since declining entry costs, perhaps the most natural explanation for increased foreign market entry, do not explain the dramatic increase in exporting, what does? To answer this question, we combine elements of the workhorse gravity model in international trade with the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition. This decomposition method has been widely used to study topics such as the reasons for the rise in US female labour force participation and the decline in US union membership over time. This approach helps us overcome a set of challenges to identification in our estimations. In particular, the decomposition ensures that developments within the sample outside of the first year do not affect our econometric results.

We find that improvements in telecommunications, free trade agreements, and foreign economic growth, in that order, were the primary drivers of these trends for US firms. Broader changes in tariffs, changes in the real exchange rate, and geopolitical events like the fall of the Soviet Union all played small roles. In looking at these changes across different types of firms, we generally find a similar ranking of effects. One notable result here is that for smaller firms free trade agreements played a more important role, while for larger firms changes in foreign market size were more important. We also come to similar conclusions when treating the normalization of trade relations with China in 2001 as a free trade agreement.

Conclusion

While much has been written on the consequences of globalisation, our understanding of why these trends are occurring is only just starting to take shape. A better understanding of the causes of globalisation could help to mitigate the costs of these trends while unlocking their benefits. It could also help in understanding how globalisation might continue. Our work focuses on the experience of the US, but this may be different than that of other countries. The free trade agreements that the US signed during this period, for example, are certainly specific to its own experience. Yet both worldwide industry level export data and firm level data from Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Mexico, and Morocco suggest that these trends are not exclusive to the US. Further analyses of the experiences of other countries would help greatly in our understanding of the globalisation of firms, one of the most important developments of our time.

Authors' note: Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Census Bureau, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, or any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. All results have been reviewed to ensure that no confidential information is disclosed.

References

Baldwin, R and P Krugman (1989), “Persistent trade effects of large exchange rate shocks”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 104(4): 635–654.

Bernard, A B and J B Jensen (2004), “Why some plants export”, Review of Economics and Statistics 86(2): 561–569.

Bernard, A B and J B Jensen (2009), “Importers, exporters and multinationals: a portrait of firms in the U.S. that trade goods”, in T Dunne, J Jensen and M Roberts (eds), Producer Dynamics: New Evidence from Micro Data, University of Chicago Press, pp. 513–556.

Cairncross, F (1997), The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution Is Changing our Lives, Harvard Business School Press.

Friedman, T L (2005), The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Das, S, M J Roberts and J R Tybout (2007), “Market entry costs, producer heterogeneity, and export dynamics”, Econometrica 75(3): 837–873.

Dixit, A (1989), “Entry and exit decisions under uncertainty”, Journal of Political Economy 97(3): 620–638.

Freund, C L and D Weinhold (2004), “The effect of the internet on international trade”, Journal of International Economics 62(1): 171–189.

Kehoe, T J and K J Ruhl (2013), “How important is the new goods margin in international trade?”, Journal of Political Economy 121(2): 358–392.

Lincoln, W F and A H McCallum (2018), “The rise of exporting by U.S. firms”, European Economic Review 102: 280-297.

Melitz, M J (2003), “The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity”, Econometrica 71(6): 1695–1725.

Roberts, M and J R Tybout (1997), “The decision to export in Colombia: an empirical model of entry with sunk costs”, American Economic Review 87(4): 545–564.