The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the globe extremely swiftly. In 2007-2008, it took more than a year from the appearance of cracks in the US subprime mortgage market to the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, and the trough of the ensuing recession was reached in both the US and the euro area in the second quarter of 2009 (NBER, CEPR). In 2019-2020, it took 3½ months from the first reports on a novel virus in Wuhan to the imposition of lockdowns around the world in late March, and the trough of output in Europe is likely to have been reached in the course of the second quarter.

The recovery will be more drawn out than anticipated

In an environment that is so fast-moving, standard monthly or quarterly macroeconomic indicators are of limited use. Moreover, they are often released with substantial lags – for example, the preliminary flash estimates for second-quarter GDP will become available at the end of July. Faced with the fast pace of events as well as vast uncertainty about the dynamics of the pandemic and the economic impact of containment measures, forecasters have turned to alternative data to gauge developments in quasi-real time.1

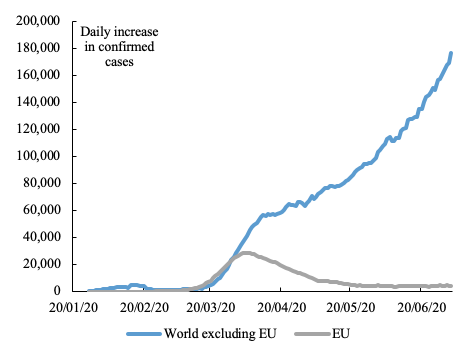

- Medical indicators depict a peak of new COVID-19 infections in the EU in the first half of April and a stabilisation at low levels since the second half of May. At the same time, the global number of new infections continues to be on the rise, with no clear indication of an inflection point (Figure 1a).

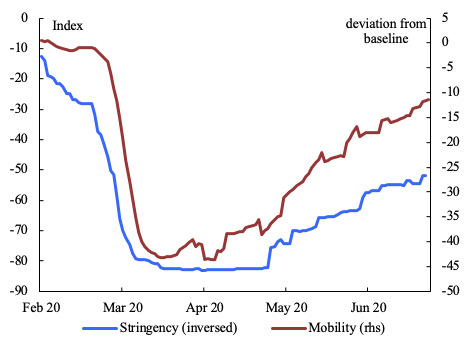

- Indicators related to containment measures illustrate the swift imposition of severe restrictions and their gradual lifting as well as the behavioural responses to the pandemic and related containment measures, for exaple in mobility patterns (Figure 1b).

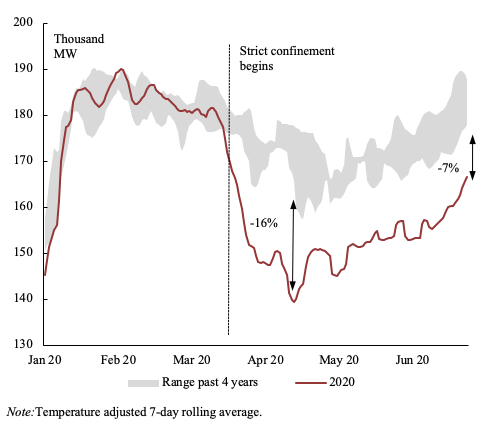

- Economic activity indicators provide an early estimate of the depth of the economic fallout, for example measures of energy use (Figure 1c) and pollution as well as financial and survey data.

Figure 1 Pandemic and containment measures, real-time data

a) Daily new infections

b) Stringency of containment, mobility, euro area

c) Electricity use

Sources: 1a) ECDC; 1b) Oxford University, Google; 1c) ENTSO-E, NOAA

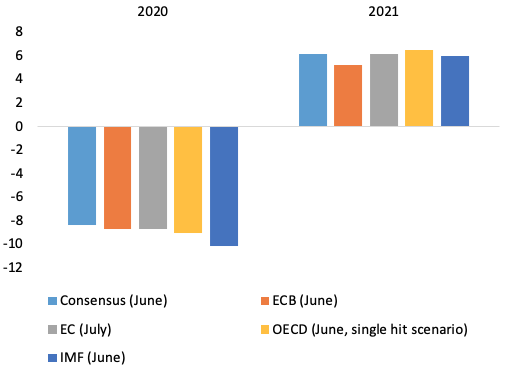

Taken together, these data suggest that economic activity in the euro area was hit harder in the second quarter than initially expected. Consequently, the Commission’s summer interim forecast (European Commission 2020d) has revised GDP lower for this year, mostly on account of a later and more gradual lifting of containment measures than anticipated earlier. Other international institutions and private-sector forecasters have also revised their projections for 2020 lower in their latest forecasts (Figure 2).

High-frequency data now also point to a rebound of activity in the past few weeks. The Commission’s business surveys for June not only confirm an increase of output expectations but also a bottoming-out of actual activity. The assessment of recent production improved strongly in industry in June and robustly in the retail sector, but only just points to a turnaround in services.

Despite some differences in the quantification of the negative impact this year and the subsequent rebound, there is broad agreement about the general outlook, and in particular that the recovery will remain incomplete by 2021. The Commission’s Summer interim forecast is based on a number of assumptions regarding the pandemic and the lasting effects of the recession. In particular, the forecast baseline assumes no major second wave of infections. By contrast, the ongoing global spread of the virus, in particular in the US and in a number of emerging market economies, is expected to dampen the rebound of global activity and world trade. It is further assumed that containment measures in Europe will continue to be gradually eased, but that social distancing and consumers’ prudence will continue to hold back the recovery in activities that involve personal contact, such as tourism and recreational activities. The measures that have been put in place to protect jobs and shield firms from bankruptcy are assumed to be effective, without however being able to avoid unemployment increases and insolvencies altogether.

Figure 2 Recent GDP growth forecasts for the euro area

Sources: DG ECFIN, ECB, IMF, OECD, Consensus

On this basis, euro area (EU) GDP is now projected to drop by 8¾% (8¼%) this year and to increase by 6% (5¾%) in 2021. The quarterly profile implies that output in the fourth quarter of 2021 will still be 2% below the level in the fourth quarter of 2019 in the euro area, and 1¾% in the EU. In the Spring forecast (European Commission 2020a), this gap was projected at ½% for both areas.

Remaining restrictions and voluntary social distancing are likely to affect sectors to which personal interaction is central more permanently than others. Estimations carried out by DG ECFIN’s geographical desks confirm that the sectors hit the most in the second quarter are tourism and recreational services, and to a lesser extent manufacturing, construction and wholesale and retail trade. Accommodation and food services, as well as recreational services, are the sectors in which activity is expected to remain the most subdued also in the second half of this year.

The increase of the unemployment rate, to 6.7% in May, has so far been remarkably mild in the EU as a whole, on the back of strong policy support for keeping workers in employment relationships during the episode of output losses. However, some laid-off workers have not been able to actively look for jobs during the lockdowns or withdrew from the labour market to care for relatives and were therefore not counted as unemployed. The drop of hours worked by 2.6% already in the first quarter points to significantly larger shifts in the underutilisation of labour in recent months than unemployment data suggest.

Looking ahead, bankruptcies are likely to rise in the most persistently affected sectors, and some further rise of unemployment will be hard to avoid. This combination will lead to some lasting crisis impact (hysteresis), even in the relatively mild forecast baseline.

Cross-country differences will be large

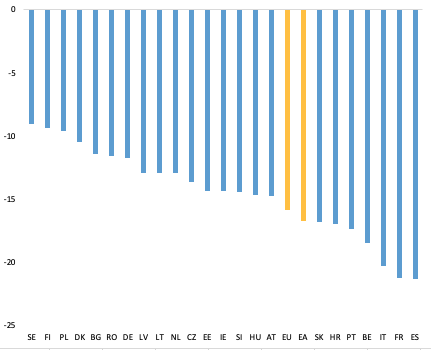

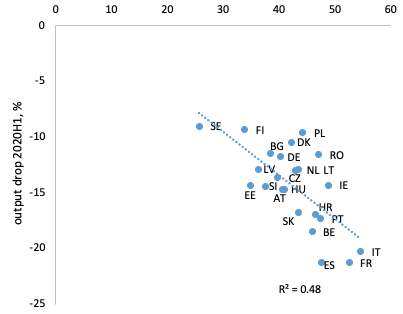

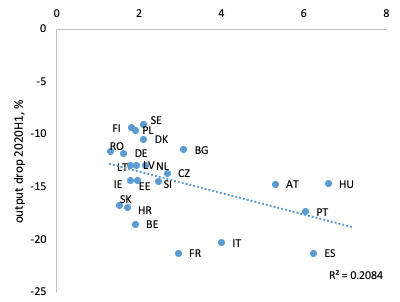

The negative impact of the crisis is set to differ widely across EU Member States. The pandemic has hit countries simultaneously and the nature of the shock appears to have been very similar. Nonetheless, the projected loss of output over the first two quarters of 2020 compared to the last quarter of 2019 ranges from less than 10% in Finland, Sweden and Poland to more than 20% in Italy, France and Spain (Figure 3a). These differences in the initial impact reflect the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak, the stringency of containment measures as well as different economic structures. In particular, an important share of personal services such as accommodation and food services and a large dependence on tourism increased the negative impact on Member States (Figures 3b and 3c).2

Figure 3 Cumulated loss of output by 2020Q2, drivers

a) Cumulated GDP loss

b) GVA share of accommodation and food services

c) Stringency of containment (index average 32020H1)

Sources: 2a) DG ECFIN; 2b) DG ECFIN, Oxford University; 2c) DG ECFIN, Eurostat.

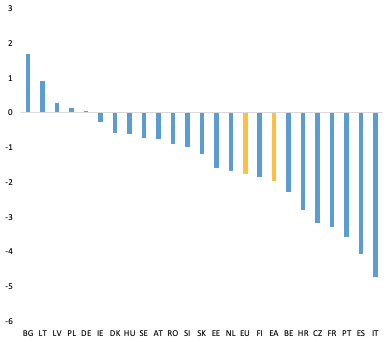

These divergences are likely to persist also in the recovery. The countries hardest hit so far are expected to continue lagging behind at the end of the forecast horizon (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Cumulated change of GDP, 2019Q4 to 2021Q4

Source: DG ECFIN

Labour market developments could amplify the divergence even further. Here, differences across Member States are also pronounced, reflecting not only output losses related to the severity of the pandemic and sectoral exposure to COVID, but also institutional features such as the share of short-term contracts and the design and strength of policy responses such as partial unemployment schemes. Differences in average firm size between Member States may also play a role, with small firms being financially more constrained than larger firms. Doerr and Gambacorta (2020) construct a regional employment risk index on the basis of firm size and sectoral specialisation that shows particularly high values for Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal, Slovenia and parts of France. This puts an emphasis on the need for targeted measures that reflect the geographical differences in Europe’s economic fabric.

Need for a large recovery package responsive to sectoral and geographical differences

The Summer interim forecast underscores the need to accompany the recovery with a major fiscal support as outlined in the Commission’s ‘Next Generation EU’ proposal (European Commission 2020b). The downward revisions to the outlook for GDP point to a larger investment gap, indebtedness and financing needs of the public and private sectors than estimated in May, highlighting the urgency even more.

During the past decade, external demand made a major contribution to the recovery from the Great Recession that started in 2009 and the recovery from the sovereign debt crisis since 2013. By contrast, exports are unlikely to come to the rescue this time around, as the COVID-19 pandemic is not only a truly global crisis, but it also continues to affect many of the EU’s largest trading partners particularly heavily. This is confirmed by the continued fast spread of the pandemic outside Europe’s borders and ensuing downward revisions to the global growth outlook. More onus is therefore on endogenous domestic demand as a key driver of the recovery.

Large funds have been made available by Member States and the EU to protect workers’ incomes and prevent bankruptcies during the crisis, but this alone will not be enough to ensure a swift and complete recovery (Revoltella et al. 2020). Avoiding persistent drags from a debt overhang and unemployment hysteresis and minimising the still very large downside risks will require continued policy support.

Careful targeting of this support is essential. In line with the downward revisions to GDP, the shortfall of investment in the EU in 2020 and 2021 compared to the path expected last autumn is even larger than estimated in the spring forecast (European Commission 2020a). The outlook for economic activity in the countries and sectors most affected by the crisis has been revised down further. Often faced with limited fiscal space, they are also projected to recover more slowly than others. Left unaddressed, these divergences between Member States could become persistent and lead to fragmentation within the Single Market and the monetary union. Moreover, the recovery offers the opportunity to boost investment with an orientation towards the green and digital transitions.

With the recovery plan ‘Next Generation EU’, the Commission proposes to act on these differentiated financing needs through a combination of several instruments amounting in total to €750 billion over four years (European Commission 2020b, Verwey et al. 2020).

Political agreement on this package is needed in the coming weeks in order to implement this fiscal stimulus in a timely manner.

References

Chen, S, D Igan, N Pierri and A Presbitero (2020), “The economic impact of Covid-19 in Europe and the US: Outbreaks and individual behaviour matter a great deal, non-pharmaceutical interventions matter less”, VoxEU.org, 11 May.

Deb, P, D Furceri, J D Ostry and N Tawk (2020), “The economic effects of COVID-19 containment measures”, VoxEU.org, 17 June.

Doerr, S and L Gambacorta (2020), “Covid-19 and regional employment in Europe”, BIS Bulletin 16, May.

European Central Bank (2020), “Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area”, June.

European Commission (2020a), European Economic Forecast Spring 2020, European Economy Institutional Paper 125.

European Commission (2020b), “Europe's moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation”, COM(2020) 456 final.

European Commission (2020c), “Identifying Europe’s recovery needs”, SWD(2020) 98 final.

European Commission (2020d), European Economic Forecast Summer 2020 (interim), European Economy Institutional Paper 132.

Haldane, A (2020), “The Second Quarter”, speech, 30 June.

Hale, T, S Webster, A Petherick, T Phillips, and B Kira (2020), “Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker”, Blavatnik School of Government.

International Monetary Fund (2020), World Economic Outlook Update, June.

Leiva-León, D, G Pérez-Quirós and E Rots (2020), “The Global Weakness Index: Reading the economy’s vital signs during the COVID-19 crisis”, VoxEU.org, 14 May.

OECD (2020), Economic Outlook, Vol. 2020, Issue 1, June.

Revoltella, D, R Strauch and M Verwey (2020), “Helping people, businesses and countries in Europe”, ESM Blog.

Verwey, M, S Langedijk and R Kuenzel (2020), “Next Generation EU: A recovery plan for Europe”, VoxEU.org, 9 June.

Endnotes

1 Haldane (2020) and references therein; several recent VOX columns including: Leiva-León et al (2020); Chen et al (2020); and Deb et al (2020).

2 In a simple regression, the average stringency of containment measures in the first half of 2020 and the gross-value-added share of accommodation and food services explain more than half of the cross-country variation of output in the first half of 2020.