The amount of time college students spend studying has declined over the last 50 years. Between 1961 and 2004, the average study time of college students fell from 24 hours a week to approximately 11 hours per week. The percentage of students studying fewer than five hours a week increased from 7% to 25% (Babcock and Marks 2011).

This is concerning because college students are studying far fewer hours than are required to succeed. Many college administrators and faculty recommend two or three hours of study for each hour a student spends in class, implying 25 to 35 hours of effort outside of class for someone enrolled full-time (there is a reason they call it ‘full-time’ enrolment).

Obviously the quality of the work a student does when studying, the content of the course, access to student services, and other factors help determine how much study time each student needs and, ultimately, how well that student performs. But even the most promising students are unlikely to make the Dean’s List without sufficient time reviewing, practicing, and thinking. Research supports the view that students would perform better if they studied more (Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner 2008, Metcalfe et al. 2011, Lindo et al. 2012, and Grodner and Rupp 2013).

As study time in higher education institutions falls, other problems arise. These include high dropout rates (Bound et al. 2010), limited skill development (Arum and Roska 2011), and high student loan default rates (Scott-Clayton 2018). Increasing study time may represent a necessary – but not sufficient – change to address these issues. Any effort to improve academic achievement stands a better chance of succeeding if it can increase study time first.

How much are students studying, and could they study more?

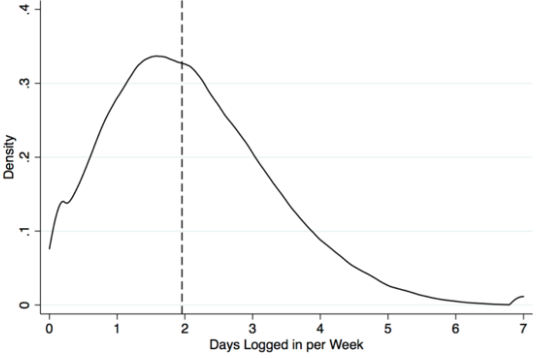

In a new study (Oreopolous et al. 2018), we describe our own effort to increase study time and subsequent academic achievement at three higher education campuses: Western Governors University (WGU), an asynchronous online university, and two traditional campuses in the University of Toronto (U of T) system. Figure 1 shows that the median student at WGU logs on to the platform on only two days a week.

Figure 1 Days logged in per week for students at Western Governors University

Source: Oreopolous et al. (2018).

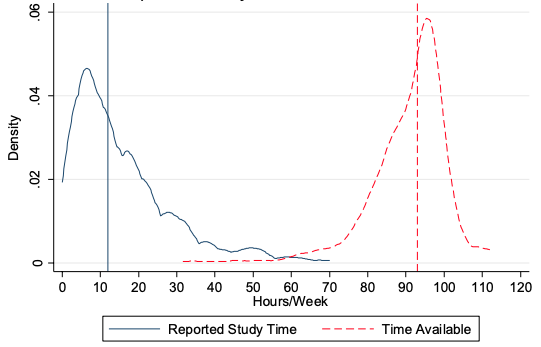

The blue solid line in Figure 2 shows that the median student at U of T studies only 12 hours a week, and the modal study time is only six hours a week.

Figure 2 Student use of time at the University of Toronto

Source: Oreopolous et al. (2018).

Perhaps students simply do not have the time available to study. To explore this possibility, before the semester began we asked U of T students to identify the amount of time they needed for commitments that could keep them from studying, including work, commuting, time in class, and sleep.

Their available study time is the red dotted line in Figure 2. The median student has more than 90 available hours to study each week. No students report having fewer than 30 hours available to study each week. Lack of available time is not keeping students from their studies.

Study time matters

This would not matter if study time and performance are not related. In our research (Oreopolous et al. 2018) we also explore the relationship between studying and academic outcomes.

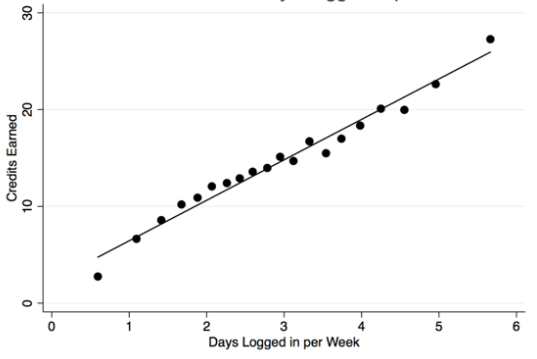

Students at WGU pay for a flat-fee per six-month semester, all courses are graded 'pass' or 'fail', and they can earn as many credits as they like. Therefore, the most relevant academic outcome in each term is how many credits students earn. Figure 3 shows a clear and highly positive relationship between how often students log in to work on their courses, and how many credits they earn.

Figure 3 Relationship between days logged in and credits earned at WGU

Source: Oreopolous et al. 2018.

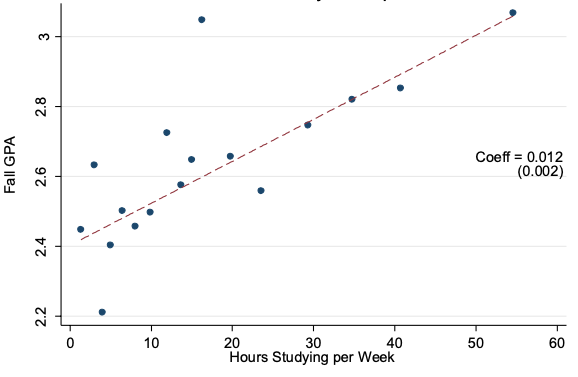

At U of T, we also find a strong positive correlation between studying and academic performance. Figure 4 shows the positive relationship between study hours and course grades. We find that a one-standard-deviation increase in study time is correlated with an increase in semester GPA by 15% of a standard deviation.

Figure 4 Relationships between fall semester study time and GPA at the University of Toronto

Source: Oreopolous et al. 2018.

An experiment to improve study time

We designed and implemented two low-cost college experiments. One was in a sample of more than 6,000 students at WGU, and one was in a sample of more than 3,500 students at U of T (across two distinct campuses).

Students randomly assigned to the treatment group were given online information to explain the benefits of sufficient study time as part of a compulsory ‘warm-up' exercise at the start of the semester. They were guided to create a detailed weekly calendar that would include sufficient regular study time, which they could transfer to their electronic calendars on their phones or computers. To make sure their plans remained salient, we also encouraged students at the U of T campuses to provide their phone numbers so that they could receive reminders, study tips, and access to a virtual coach who would check in weekly about any questions or problems.

Students at WGU were encouraged to download a mobile application. This would send them reminders throughout the academic year. Students in the control groups at the U of T campuses were given a personality test, while students in the control group at WGU did not receive the planning module, but still completed the standard online student orientation.

Treated students appeared to be highly engaged in the planning and coaching aspects of the programme. They created and used detailed weekly study plans, responded thoughtfully to questions about anticipating challenges throughout the semester, and almost half of U of T’s participants engaged regularly with their coaches by responding to text messages each week.

Despite this, we found precisely no impact on academic outcomes across all campuses. There were no treatment effects on credit accumulation or course grades at U of T, and no treatment effects on student credit accumulation or retention at WGU. These results hold even when looking at subgroups of students in which we might expect larger-than-average effects.

Our results are consistent with an increasingly common research finding about low-cost, scalable interventions in education. These interventions seem to be effective at nudging students toward taking relatively simple, one-time actions. They are less effective at causing improvement in outcomes that require meaningful and sustained changes in student behaviour.

For example, text messages that push helpful information to students have proven effective at causing students to enrol in college once admitted (Castleman and Page 2015) or to renew financial aid (Castleman and Page 2016), but other programmes have been less successful in affecting course grades or overall GPA (Fryer 2016, Castleman and Meyer 2016, Oreopoulos and Petronijevic 2018). Similarly, encouraging people to make a concrete plan has shown promise if there is a single action such as voting (Nickerson and Rogers 2010) or getting the flu vaccine (Milkman et al. 2011). But this type of intervention has not been effective in increasing sustained actions, such as attending the gym (Carrera et al. 2018). The potential to change habits and routines using online or text-based technology seems to be much less promising than the potential to change one-time applications or actions.

So why are students unresponsive to the intervention? What more can we do? One possibility is that students simply do not want to study more because, conditional on being fairly certain of degree attainment, the high-effort strategy is not as attractive as settling for low average grades while having more free time. Most students in our sample eventually receive their degrees (at U of T) or have a fallback career if they do not graduate (at WGU).

Another possibility is that grades are a noisy predictor of ability for a wide range of students. If employers and graduate admissions committees mostly care about whether applicants achieve good grades in college, we wonder whether the choice around study habits is more discrete than marginal – that is, whether students choose between a path of low-effort-credential-focus or one of high-effort-skill-focus. In this scenario, encouraging everyone to study more may be ineffective because students are either unable to accept the significant sacrifice in time, or highly uncertain about the return from their efforts.

Low, declining study time should matter to educators and policymakers who want to encourage skill development in college. Future research in this area should aim to learn more about student perceptions the benefits of post-secondary education and the reasons they enrol. There is undoubtedly a wide variation in these perceptions and reasons (both within and across institutions) but better understanding the motivations students have, and constraints they face, would help us develop more targeted and effective policy interventions.

References

Arum, R and J Roksa (2011), Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, University of Chicago Press.

Babcock P and M Marks (2011), “The Falling Time Cost of College: Evidence form Half a Century of Time Use Data”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 93(2): 468-478.

Bound, J, M Lovenheim, and S E Turner (2010), “Why Have College Completion Rates Declined? An Analysis of Changing Student Preparation and Collegiate Resources”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2(3):1-31.

Carrera, M, H Royer, M Stehr, J Sydnor, and D Taubinsky (2018), "The Limits of Simple Implementation Intentions: Evidence from a Field Experiment on Making Plans to Exercise", NBER working paper 24959.

Castleman, B and L Page (2015), “Summer nudging: Can personalized text messages and peer mentor outreach increase college going among low-income high school graduates?" Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 115: 144-160.

Castleman, B, and L Page (2016), “Freshman Year Financial Aid Nudges: An Experiment to Increase FAFSA Renewal and College Persistence”, Journal of Human Resources 51(2): 389-415.

Castleman, B, and K Meyer (2016), “Can Text Message Nudges Improve Academic Outcomes in College? Evidence from a West Virginia Initiative”, Center for Education Policy and Workforce Competitiveness working paper 43.

Fryer, R G (2016), "Information, Non-Financial Incentives, and Student Achievement: Evidence from a Text Messaging Experiment”, Journal of Public Economics 144:109-121.

Grodner, A and N Rupp (2013), “The Role of Homework in Student Learning Outcomes: Evidence from a Field Experiment”, The Journal of Economic Education 44(2): 93-109.

Lindo, J M, I D Swensen, and G R Waddell (2012), “Are Big-Time Sports a Threat to Student Achievement?” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(4): 254-74.

Metcalfe, R, S Burgess and S Proud (2011), “Student effort and educational attainment: Using the England football team to identify the education production function”, University of Oxford, Department of Economics working paper 586.

Milkman, K L, J Beshears, J J Choi, D Laibson, and B C Madrian (2016), "Using implementation intentions prompts to enhance influenza vaccination rates", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108(26): 10415-10420.

Nickerson, D W and T Rogers (2010), “Do you have a voting plan? Implementation intentions, voter turnout, and organic plan making", Psychological Science 21(2): 194-199.

Oreopoulos, P, R Patterson, U Petronijevic, and N Pope (2018), “Lack of Study Time is the Problem, but What is the Solution? Unsuccessful Attempts to Help Traditional and Online College Students”, NBER working paper 25036.

Oreopoulos, P and U Petronijevic (2018), "Student Coaching: How Far Can Technology Go?" Journal of Human Resources 53(2): 299-329.

Scott-Clayton, J (2018), “The looming student loan default crisis is worse than we thought”, Brookings Institution Evidence Speaks Reports 2(34).

Stinebrickner, R and T R Stinebrickner (2008), “The Causal Effect of Studying on Academic Performance”, The B E Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 8(1): 1-55.