Multinational enterprises (MNEs) are arguably the most globally engaged firms in an economy – they operate in domestic and foreign markets and trade goods and services with affiliated and unaffiliated firms. MNE activities have a direct impact on their workers, suppliers, and competitors in the headquarters country (Boehm et al. 2019, Chen and Alfaro 2010, Moran and Oldenski 2013). They also shape a range of outcomes such as productivity (Bircan 2019), wages (Hijzen 2008), and even the environment (Brucal et al. 2019) in the host countries. Assessing the implications of MNE engagement requires comprehensive and longitudinal information on firms and their operations.

In a recent paper (Kamal et al. 2022), we describe a set of newly constructed crosswalks to provide a comprehensive picture of MNEs in the US economy between 1997 and 2017. We highlight the following findings averaged over this period:

- Fewer than 1% of all US firms are MNEs, but they account for disproportionate shares of economy-wide activities: 22% of employment, 30% of payroll, 40% of sales, 65% of merchandise exports, and 60% of merchandise imports.

- US-owned MNEs are larger than foreign-owned MNEs: eight times larger employment, seven times higher payroll, and five times higher sales.

- US- and foreign-owned MNEs exhibit similar levels of average pay per worker across all 50 states, but there is larger variation across sectors.

Linking BEA multinational surveys and the Census Bureau’s Business Register

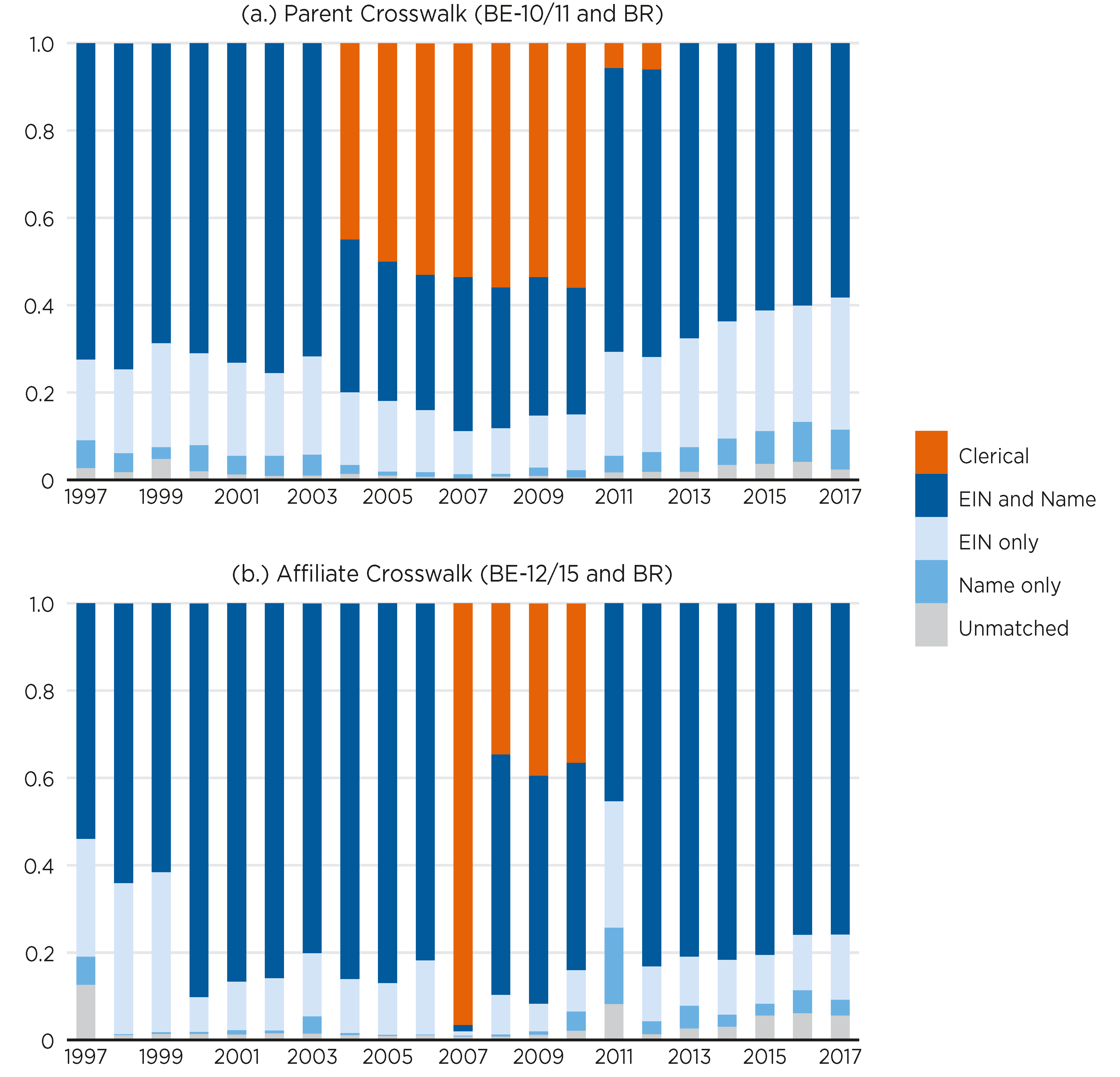

We link BEA surveys of US Direct Investment Abroad (USDIA) and surveys of Foreign Direct Investment in the US (FDIUS) to the Census Bureau’s Business Register (BR) using a combination of tax identifiers, business names, and business addresses. We employ both deterministic and probabilistic matching algorithms. The average employment-weighted match rate between USDIA and BR is 98% over the 21-year period (Figure 1a). The average employment-weighted match rates between FDIUS and BR is 97% (Figure 1b). The majority of the matches (about 94% on average) are obtained using numeric tax identifiers (Employer Identification Number, or EIN) which increases confidence in the match quality.

Figure 1 Employment-weighted match rates by match type, 1997-2017

Notes: This figure displays the annual employment-weighted match rate between (a) BE-10/11 and BR and (b) BE-12/15 and BR using employment reported in BEA surveys. “EIN and Name” denote cases that were matched using both EIN and business name; “EIN only” denotes cases that were matched using EIN only; “Name only” denotes cases that were matched using business name only; “Clerical” denotes cases that were matched using clerical review; “Unmatched” denotes cases that were not matched.

Source: Authors’ calculations using BE10-BR and BE11-BR.

Companies reporting in the direct investment surveys can have both a foreign parent and a foreign affiliate. These ‘overlap’ cases primarily arise due to the complex organisational structures of MNEs that own business units spanning a wide range of geographic and business functions. We document that 5% of the linked firms are ‘overlaps’ accounting for an average of 15% of total private sector employment among linked MNEs. We develop and implement an algorithm to assign a mutually exclusive MNE status – US-owned (domestic) or foreign-owned (foreign) – to ‘overlap’ cases using the information on equity control and employment.

To date, these crosswalks enable the most comprehensive identification of domestic and foreign-owned MNEs separately from non-MNEs in the universe of employer firms in the US economy.

The scale and scope of US multinational activities

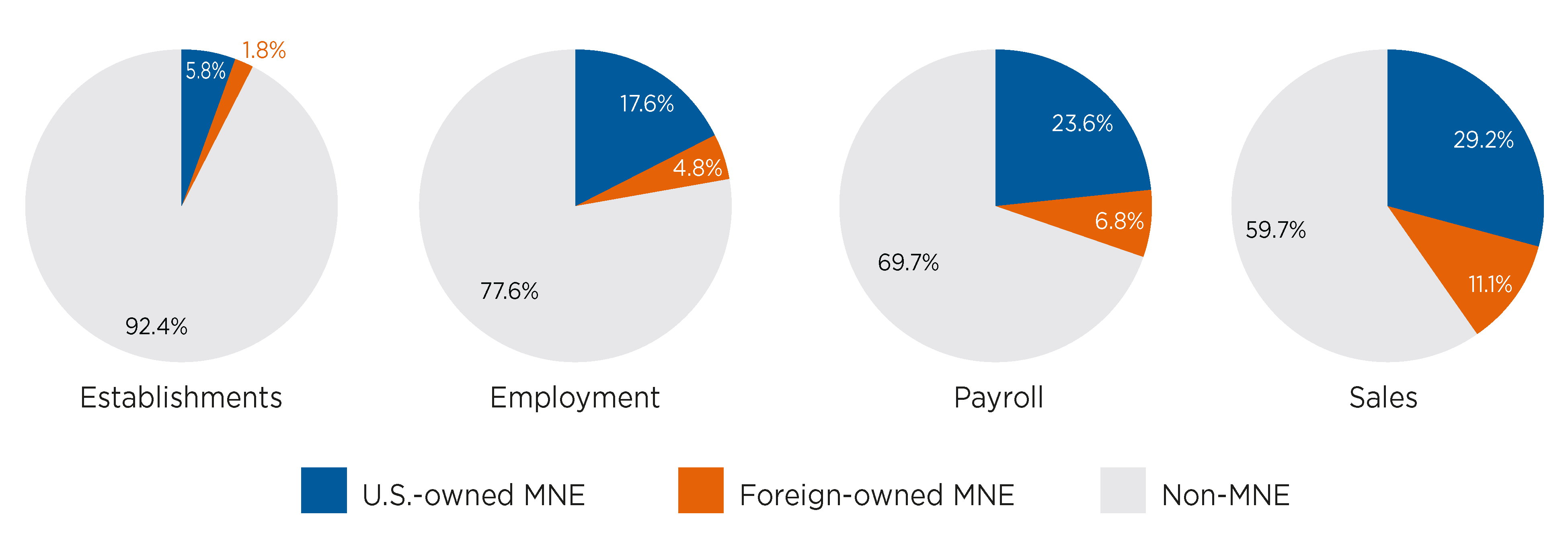

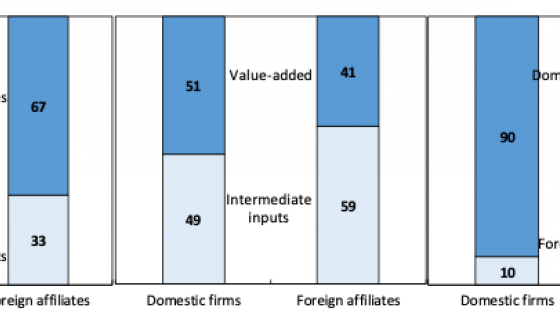

Domestic (foreign) MNEs account for about 18% (5%) of all US private-sector jobs, 24% (7%) of payroll, and 29% (11%) of sales (Figure 2). However, participation in direct investment is rare. Only about 6% (2%) of establishments are owned by domestic (foreign) MNEs; about 0.001% (0.002%) of firms are owned by domestic (foreign) MNEs. Although MNEs account for modest shares of all firms, domestic MNEs tend to be concentrated among the largest firms in the economy: on average, 47% (11%) of domestic (foreign) MNEs employ 1,000 or more workers; only 0.6% of non-MNE employment is housed at equally large firms. The uncommon prevalence of MNEs and the scale of activity is consistent with theories featuring high fixed costs associated with multinational production (Dunning 1981, Helpman et al. 2004).

Figure 2 Average share of economic activity by multinational status

Notes: This figure displays the annual share of the number of establishments, employment, sales, and payroll averaged over five Economic Census years (1997, 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017).

Source: Authors’ calculations using Economic Census, BE10-BR, and BE12-BR.

The average scope of production activities at domestic MNEs is also orders of magnitude larger than foreign MNEs: the average domestic MNE operates 128 establishments in three distinct 2-digit and five distinct 4-digit NAICS industries across 11 states and 20 counties. In contrast, the average foreign MNEs operate 18 establishments in 1.6 distinct 2-digit and two distinct 4-digit NAICS industries across four states and five counties. The difference in the average scope of goods trading activities between domestic and foreign MNEs is also sizable: the average domestic MNE exports 53 products to 25 countries and imports 30 products from 21 countries; the average foreign MNE exports 36 products to 17 countries and imports 19 products from 16 countries.

Overall, these statistics confirm that multinationals, in particular domestic MNEs, tend to organise their US activities across multiple industries and geographies and engage intensively in goods trade.

Industrial distribution of US multinational activities

Less than 20% of establishments in any given sector belong to MNEs except in information and management, where MNEs account for about a third of establishments, with US-owned MNEs accounting for the majority share. In contrast, activity-weighted shares are much higher compared to establishment count shares. Within manufacturing, domestic and foreign MNEs represent 30% and 11% of employment, respectively. Within non-manufacturing sectors, MNEs employ 50%, 47%, and 38% of workers in information, management, finance and insurance, respectively; they account for about a third of employment in wholesale, retail, and transportation. Among MNEs, domestic MNEs account for three-quarters or more of employment in these sectors. Similar patterns hold in the share of sales and payroll.

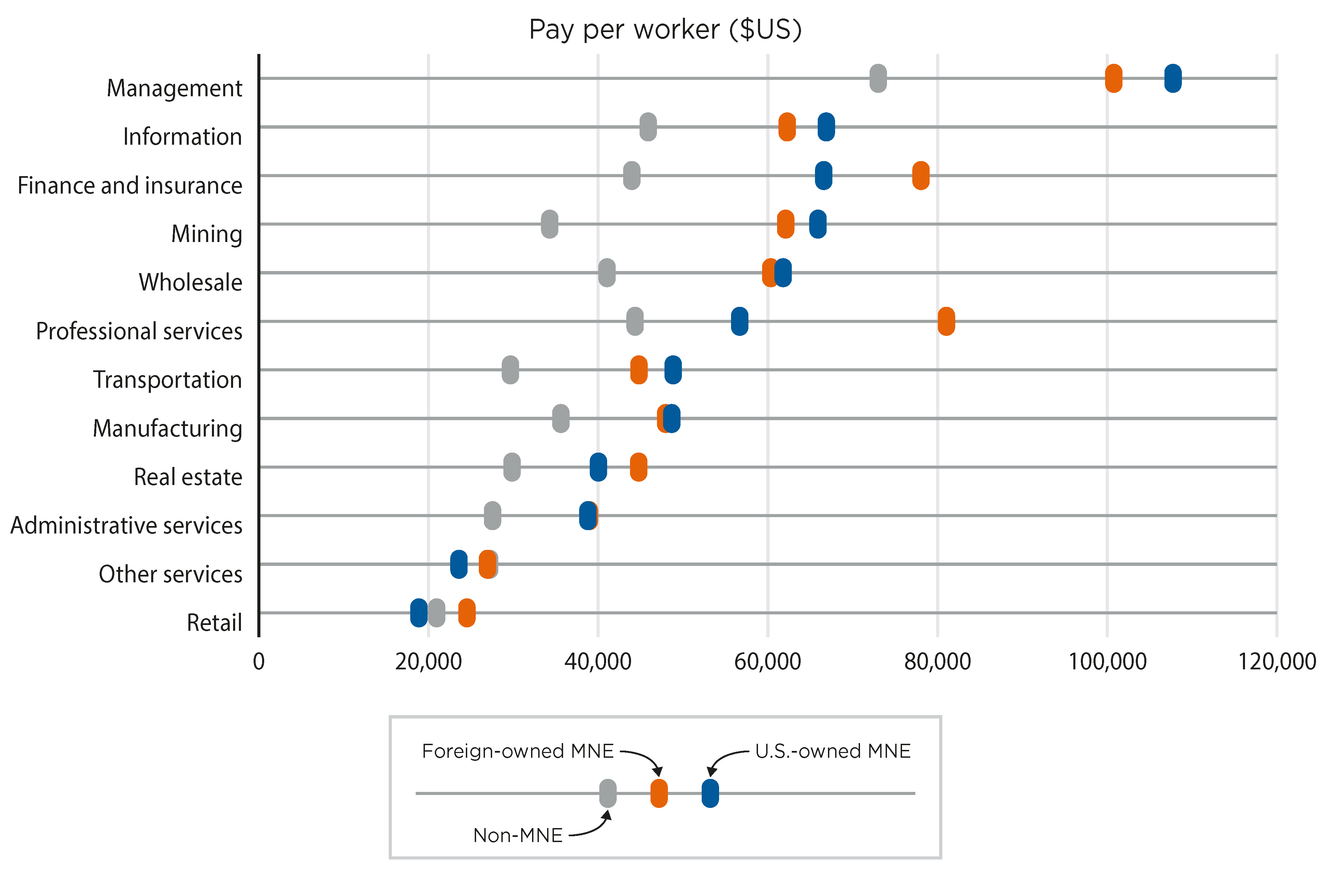

Within broad sectors, MNEs exhibit higher average pay per worker than non-MNEs. Differences between domestic and foreign MNEs tend to be small, with no clear dominance of either type of MNE. For example, domestic MNEs exhibit higher average pay per worker than foreign MNEs in management and information; however, foreign MNEs exhibit higher average pay per worker than domestic MNEs in finance and insurance, and professional services (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Average pay per worker by sector and multinational status

Notes: This figure displays the annual pay per worker (in 1,000 USD) averaged over five Economic Census years (1997, 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017) within broad sectors by firms’ multinational status. Broad sectors are one or more 2-digit NAICS as follows: Mining (21-23), Manufacturing (31-33), wholesale (42), retail (44-45), Transportation (48-49), Information (51), Finance & Insurance (52), Real Estate (53), Professional Services (54), Management (55), Administrative Services (56), Other Services (61-62, 71-72, 81).

Source: Authors’ calculations using Economic Census, BE10-BR, and BE12-BR.

Geographic distribution of US multinational activities

We find that there is very little variation within and across broad regions (defined as 9 Census divisions) in MNEs’ share of establishments, employment, sales, and payroll.

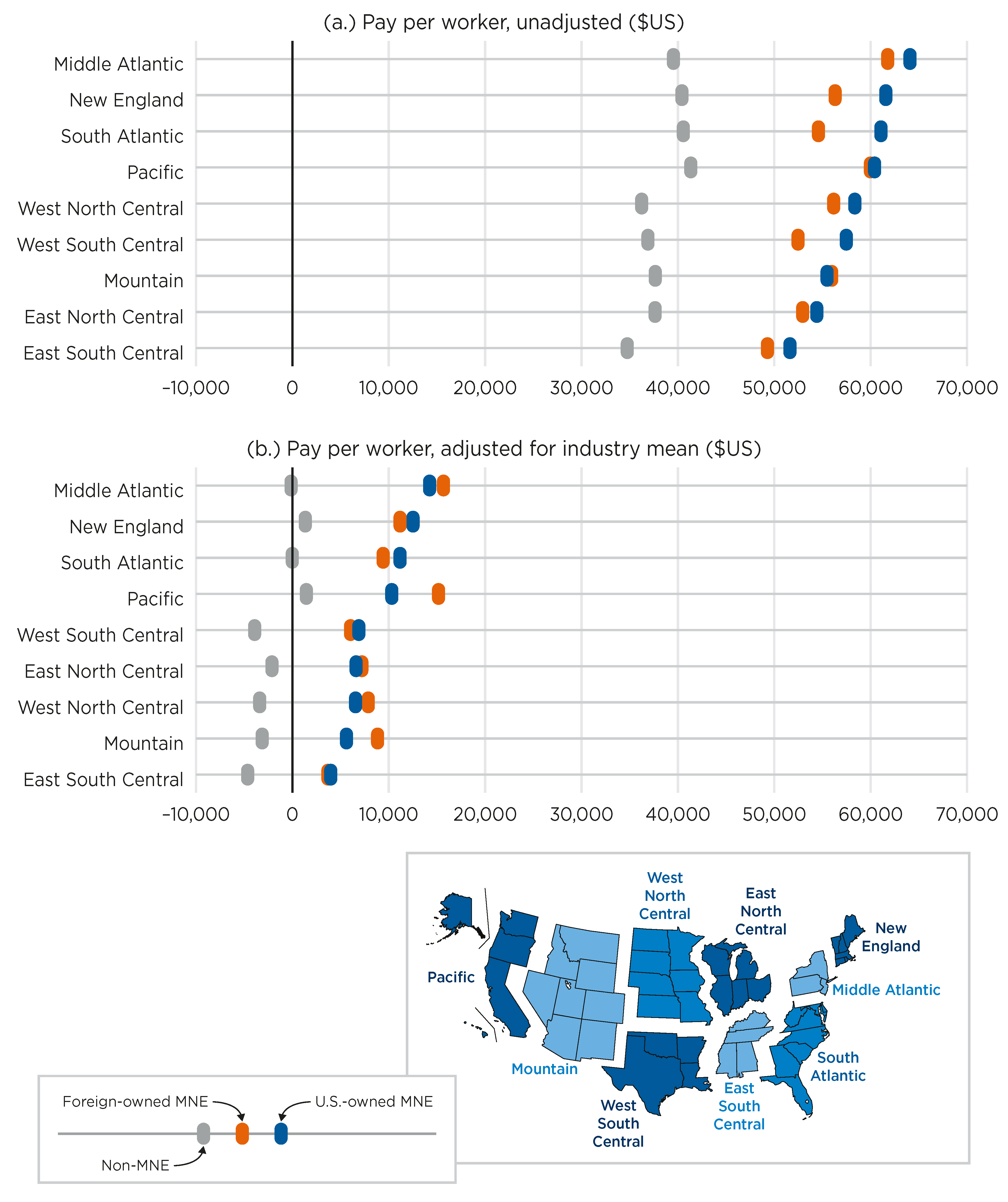

However, MNEs exhibit higher average pay per worker than non-MNEs in all regions. Still, differences between domestic and foreign MNEs in any given region are small to negligible (Figure 4a). We also report average pay per worker adjusting for industry mean to control for the industrial composition of a region (Figure 4b). The gap between non-MNEs and MNEs still persists. But now we find that foreign MNEs have higher industry-adjusted average pay per worker than domestic MNEs in the mountain and pacific regions. These results suggest that it is important to control for industrial heterogeneity when comparing multinational characteristics across space.

Figure 4 Average pay per worker by region and multinational status

Notes: This figure displays the 2017 average pay per worker (in 1,000 USD) within 9 Census divisions by firms’ multinational status.

Source: Authors’ calculations using Economic Census, BE10-BR, and BE12-BR.

Takeaways

The newly available crosswalks identifying multinationals in the Census Bureau’s Business Register will not only enable the quantification of MNEs’ contribution to US economic activities but also facilitate addressing a rich set of research questions that require detailed information on activities conducted both domestically (such as production, research and development, innovation) and abroad (such as merchandise and services trade, affiliate production). For example, what is the organisation of MNEs’ global operations, and how has it changed over time?

How do MNEs’ production activities shape industrial and spatial competition? The Census Bureau and BEA are actively working on extending the crosswalk time series on an annual basis (ICPSR 2023) and developing public-use statistics describing the business dynamics of multinational firms (US Census Bureau 2023a).

Authors’ note: The Census Bureau's Disclosure Review Board and Disclosure Avoidance Officers have reviewed this data product for unauthorized disclosure of confidential information and have approved the disclosure avoidance practices applied to this release (DRB Approval Numbers: CBDRB-FY21-CES007-003, CBDRB-FY22-CED006-0010, DMS 6907751). Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the US Census Bureau or the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

References

Antràs, P, E Fadeev, T Fort, and F Tintlenot (2022), “Global Sourcing and Multinational Activity: A Unified Approach,” NBER Working Paper 30450.

Bircan, C, (2019), “Ownership Structure and Productivity of Multinationals,” VoxEU.org, 31 January.

Boehm, C, A Flaaen, and N Pandali-Nayar (2019), “A New Assessment of the Role of Offshoring in the Decline in US Manufacturing Employment,” VoxEU.org, 15 August.

Brucal, A, B Javorcik, and I Love (2019), “Good for the Environment, Good for Business: Foreign Acquisitions and Energy Intensity,” VoxEU.org, 16 August.

Chen, M, and L Alfaro (2010), “Multinational Firms, Agglomeration, and Global Networks,” VoxEU.org, 8 January.

Dunning, JH, (1981), International Production and the Multinational Enterprise, Allen & Unwin.

Helpman, E, M J Melitz, and S R Yeaple (2004), “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms,” American Economic Review 94 (1): 300-316.

Hijzen, A (2008), “Working Conditions in the Foreign Operations of Multinational Enterprises,” VoxEU.org, 8 August.

Kamal, F, J McCloskey, and W Ouyang (2022), “Multinational Firms in the US Economy: Insights from Newly Integrated Microdata,” US Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies Working Paper 22-39.

ICPSR (2023), “Crosswalk between BEA Surveys of Direct Investment to Census Business Register”.

Moran, T, and L Oldenski (2013), “Do Multinationals that Expand Abroad Invest Less at Home?” VoxEU.org, 31 October.

US Bureau of Economic Analysis (2023), “Special Sworn Researcher Program”.

U.S. Census Bureau (2023), “Business Dynamics Statistics of Globally Engaged Firms”.

U.S. Census Bureau (2023b), “Apply For Access to Restricted-Use Census Bureau Microdata” .