Earl Grantham: Do you think she would’ve been happy with a fortune hunter?

Countess Grantham: She might’ve been. I was.

Downton Abbey, Series 1, Episode 1

Lady Cora’s mild rebuke of her husband’s hypocrisy in the opening episode of the popular international television series Downton Abbey (Fellowes 2012) is designed to remind him that it was the handsome dowry she brought from her native industrial Pittsburgh to rural Yorkshire to marry into the British aristocracy in the 1880s that saved the eponymous stately home and Earl Grantham’s family from financial ruin. This fictional storyline is based on a real-world trend. In the four decades before the outbreak of WWI, 100 daughters of US business magnates married titled members of the British aristocracy (Montgomery 1989, De Courcy 2017). Calculated another way: “Between 1870 and 1914, fully 10 percent of [male] aristocratic marriages followed this novel pattern” (Cannadine 1990). Given that the British aristocracy was generally regarded as the most exclusive club in the world outside of the British royal family, this is a remarkable phenomenon.

The premise of my recent paper (Taylor 2021) is that the rapid decline in British agricultural prices in the last quarter of the 19th century, which shrank not only the income of aristocratic landed estates but also the income of ‘commoner’ (i.e. non-aristocratic) families who owned land, led to a significant proportion of male aristocrats marrying American heiresses with rich dowries as substitutes for the traditional source – namely, brides from British families with landed estates but no titles.

British agricultural prices began their drop in the mid-1870s for several reasons, from the development of US railroads and prairies to the advent of steamships, all of which led to the UK market being flooded with cheap prairie wheat. Meanwhile, in the US, high society shunned the families of the newly rich businessmen making their fortunes during the Gilded Age. East Coast high society was the jealously guarded preserve of families who could trace their ancestry back to the earliest Dutch or English settlers, and who socially ostracised the nouveau riche business magnates and their families. So, what were these newly rich families to do? They married into the British aristocracy as a means of establishing a social pedigree, whatever the cost.

The trend likely started with the 1874 marriage of Jennie Jerome, the daughter of New York financier Leonard Jerome, and a younger son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, Lord Randolph Churchill – a union that produced Winston Churchill. Leonard Jerome settled a dowry of £50,000 on the marriage, which is about $6.5 million today if one adjusts by consumer price inflation (CPI) or around $30 million if the inflation adjustment is made using movements in real wages (aristocrats employed large retinues of servants). Two years later, Consuelo Yznaga, the daughter of Antonio Yznaga – who had made his fortune in West Indian sugar plantations before relocating to Newport, Rhode Island – married the heir to the Duke of Manchester, thereby proving that the highest social rank below royalty was not beyond the scope of an American business family’s daughter. The dowry settlement was £200,000 (about $26 million today CPI adjusted or around $130 million real-wage adjusted).

Perhaps the most celebrated (or notorious) American-aristocratic marriage of the period took place at the height of the trend, in 1895, when the family of the US railroad magnate William K. Vanderbilt became allied to one of Britain’s most prestigious aristocratic families with the marriage of his daughter Consuelo to the 9th Duke of Marlborough. The dowry settlement was $2.5 million, which is a CPI-adjusted $82 million today, or over $400 million in real-wage adjusted terms: money that restored the family fortunes and, quite literally, the palatial Marlborough ancestral seat of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire.

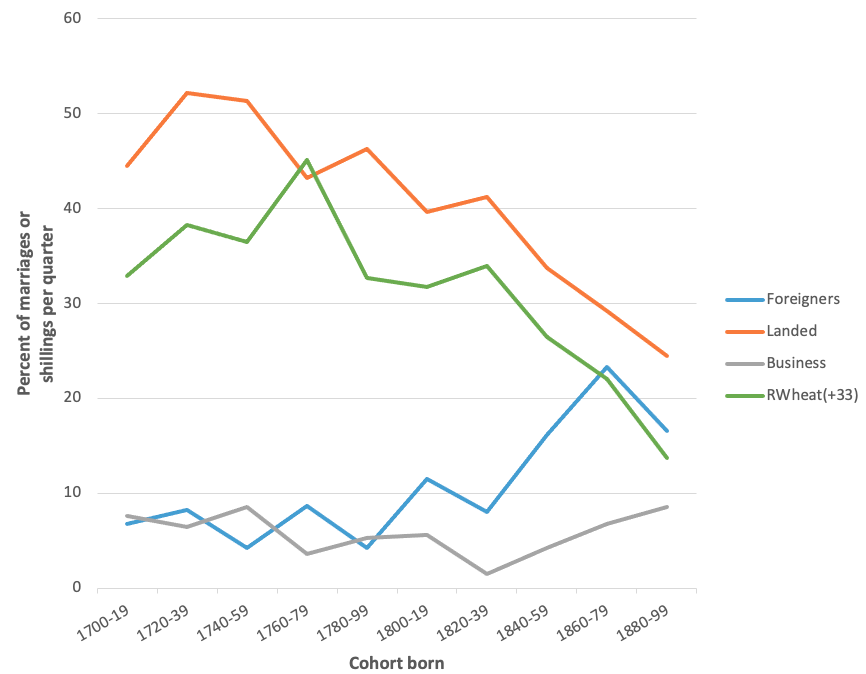

Figure 1 shows the percentage of marriages between British aristocrats and non-aristocrats (‘out-marriages’) for British males born in 20-year cohorts between 1700 and 1899, as well as the 20-year average real price of wheat in London 33 years later (33 being the average age at which British aristocrats married during the 18th and 19th centuries). The positive correlation between the decline in the price of wheat and the percentage of brides from landed families marrying into the aristocracy is striking, as is the rise in the percentage of ‘out-marriages’ to foreigners as wheat prices fell.

Figure 1 'Out-Marriages' of the British aristocracy to foreigners – and of British 'landed' and business families – and the real price of wheat

Note: The series for the percentages of ‘out-marriages’ of male aristocrats to daughters of foreigners and of British landed and business families are from Thomas (1972). The series RWheat(+33) is the average real price of wheat in London (shillings per quarter; deflated by the consumer price index) for 20-year periods corresponding to the birth cohort periods but 33 years later; thus, for example, the observation for 1740–1759 is the average London real wheat price for the period 1773–1792, corresponding to the average real price of wheat during the likely years of marriage of the cohort born from 1740–1759. Sources for the wheat price data are Clark (2004) for 1700–1769, and Solar and Klovand (2011) for 1770–1914; the source for the CPI data used to deflate the wheat price series is Clark (2018).

In my research paper, I use simple probability theory to demonstrate that the likelihood of these correlations appearing purely by chance over these long periods is miniscule. I also show that aristocratic marriages to US heiresses were part of a wider, less pronounced phenomenon whereby non-American foreign brides were also substituted for British non-aristocratic landed brides during much of the 19th century, when agricultural prices declined. In addition, I find significant evidence of substitution for landed brides with British business family brides over the whole of the 18th and 19th centuries; as shown in Figure 1, this trend is less marked than the rate of admission for foreign brides, but it nevertheless increased over the course of the two centuries.

In economic theory terms, these results are consistent with a form of ‘positive assortative matching’ in the marriage market (Becker 1973), supplemented by a lump-sum transfer to the bridegroom (i.e. a dowry, see Becker 1991). During a period of agricultural decline, there may be cash constraints on lump-sum transfers from landed families just when landed aristocrats need money most, allowing unlanded but rich families to offer higher lump-sum transfers in order to compensate for the lower level of prestige associated with non-landholders – a phenomenon that may perhaps be termed the ‘Downton Abbey effect’.

References

Becker, G S (1973), ‘A Theory of Marriage: Part I’, Journal of Political Economy 81(4): 813–846.

Becker, G S (1991), A Treatise on the Family, enlarged ed., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 126–129.

Cannadine, D (1990), The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 347.

Clark, G (2004), ‘The Price History of English Agriculture, 1209–1914’, Research in Economic History, 22: 41–124.

Clark, G (2021), ‘What Were the British Earnings and Prices Then? (New Series)’ Measuring Worth.

De Courcy, A (2017), The Husband Hunters: American Heiresses Who Married into the British Aristocracy, New York: St Martin’s Press.

Fellowes, J (2012), Downton Abbey: The Complete Scripts, Season One, New York: William Morrow.

Montgomery, M (1989), Gilded Prostitution: Status, Money and Transatlantic Marriages, 1870–1914, New York: Routledge.

Solar, P M and J T Klovland (2011), ‘New Series for Agricultural Prices in London, 1770–1914’, Economic History Review 64(1): 72–87.

Taylor, M P (2021), ‘The Downton Abbey Effect: 18th and 19th Century British Aristocratic Marriages and Agricultural Prices’, CEPR Discussion Paper 16209.

Thomas, D N (1972), ‘The Social Origins of Marriage Partners of the British Peerage in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’, Population Studies 26(1): 99–111.