Given the evidence that non-cognitive skills are strongly related to adult outcomes (Kocher et al. 2012) and the rising return of social skills on the labour market (Deming 2017), the question of whether intervention on those skills alone can generate long-term impacts is key. Yet, there is little concrete evidence of the lifelong benefit of investing in non-cognitive skills such as self-control or social skills. Well-known longitudinal studies – in particular the Perry Preschool Programme evaluated by the Nobel-prize winner James Heckman (Heckman et al. 2010, Heckman 2017) or the ABeCeDarian programme and the Head Start programme (Bailey et al. 2021) – have shown that early intervention for disadvantaged children can be highly efficient in the long-run (Elango et al. 2016), but these experiments were not designed to disentangle the role of non-cognitive skills and cognitive/academic skills.

In our new paper (Algan et al. 2022), we show a causal link between childhood non-cognitive-skills training and long-term outcomes: higher trust and self-control, better school performance, lower criminality, higher employment, and lower dependence on social transfers as adults.

A lifelong randomised experiment for at-risk boys started in the 1980s

In the 1980s, as part of a larger study on juvenile development, kindergarten teachers in Montreal identified 250 boys with behaviour problems. Two groups were randomly selected from these boys, one of which (the treatment group) was invited to participate in a new social-skills training programme. The other (the control group) was not invited to participate in the programme, but still had access to resources available to public school children.

The boys participating in the programme were placed into small groups with pro-social boys, and together they were given social-skills training by professionals once per week during the school term over two years. Each week, the group would address a different topic – for example, how to react to teasing or how to invite someone to play with you. Participants would discuss perspective-taking, make action plans, model behaviour, and be coached through role-playing. Parents and teachers were kept informed of the sessions and encouraged to praise the boys for practising the learned skills. The programme focused exclusively on non-cognitive skills and provided no academic or cognitive coaching.

Over the years, the team of psychologists at the University of Montreal, led by Richard Tremblay, followed the treatment and control groups. They conducted annual surveys of the parents, the boys, and the teachers, and collected school records. In the boys’ young adulthood, the researchers continued to conduct surveys and obtained administrative data on school completion and arrests. When the participants were in their late 30s, their administrative tax records were matched with the large longitudinal dataset, in partnership with Statistics Canada. This resulted in a rich and unparalleled longitudinal dataset that includes subjective information from multiple sources and administrative data.

A cascade of impacts

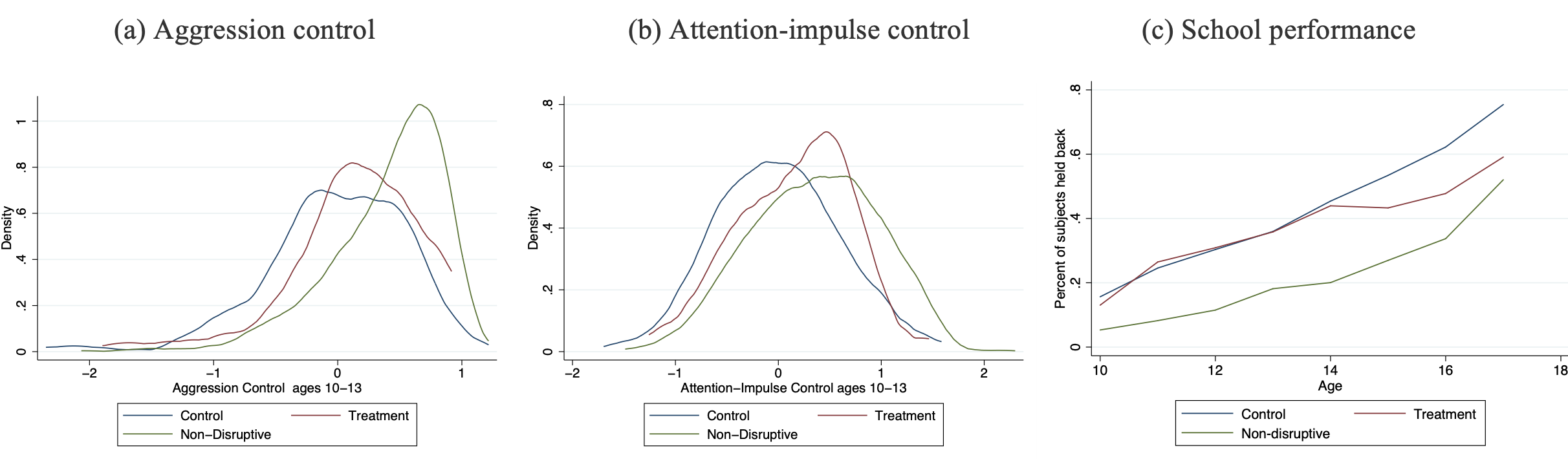

In adolescence, the boys in the treatment group had higher levels of trust, aggression control, and attention control than the boys in the control group (Figure 1 and Figure 3a). There were no differences in terms of friendliness, altruism, self-esteem, or verbal IQ.

Figure 1 Impacts on self-control (aggression and attention) and school performance

In early adolescence, school performance was the same for the treatment and control groups, but as time went on, the treatment group began to pull ahead in grades and the likelihood of being held back or assigned to special education classes (Figure 1c). In adulthood, boys in the treatment group were almost 50% more likely to have finished secondary school.

As young adults, the participants were more likely to report being part of a social group of some kind (such as a club), but no more likely to report volunteering (which makes sense, given that there was no impact on altruism). They were also almost half as likely to have been convicted of a crime by age 24 than the young men who had been in the control group.

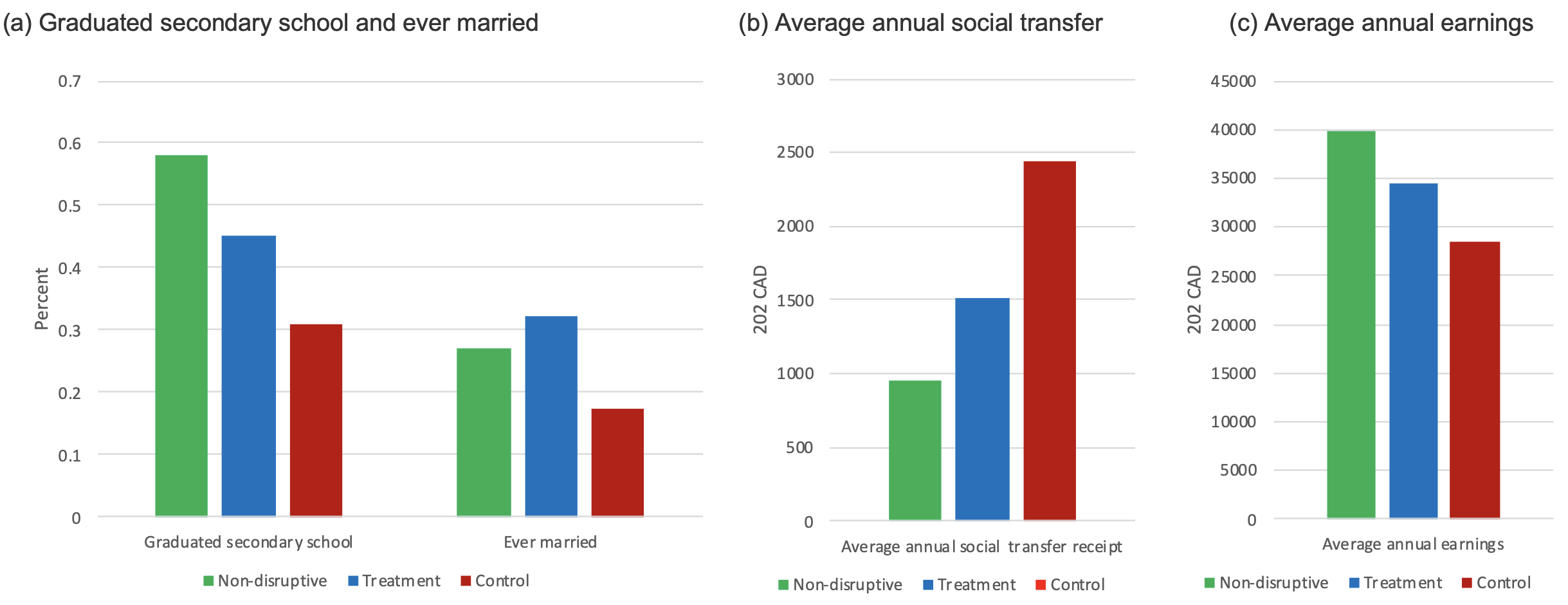

The impacts continued into adulthood. Tax data revealed that men who had been in the treatment group as children earned 20%, or about 5,708 Canadian dollars (C$), more per year and received 40% (about C$929) less in social transfers per year, were more likely to be married, and paid more dues to professional organisations such as unions (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Selected main impacts of social-skills training

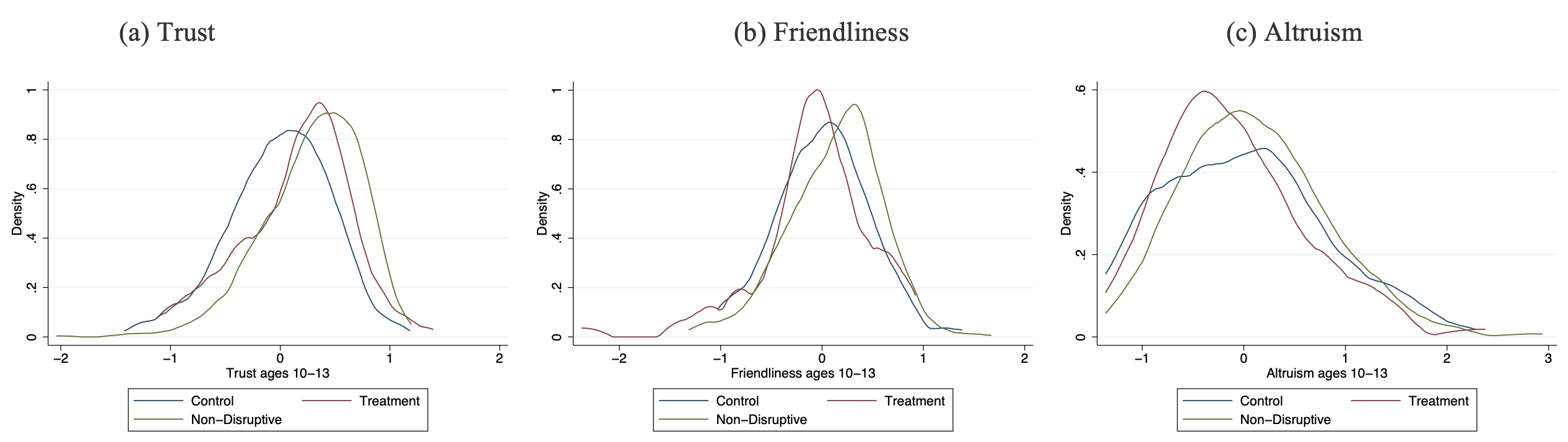

Decomposing pro-sociality

‘Pro-social’ interventions are often thought of as improving social behaviour across dimensions such as altruism, trust in others, and socialisation. While these dimensions may be related, they are different just as self-control in terms of concentration is different from self-control in terms of not being aggressive. Using factor analysis on many behavioural and attitude questions from respondents and psychological inventories allowed these three pro-social characteristics to emerge as distinct behaviours, only one of which (trust) was impacted by the programme (Figure 3). That participants did not show a higher likelihood of volunteering or contributing to charity, though they did show higher group membership, underscores the importance of distinguishing different pro-social behaviours.

Figure 3 Trust, friendliness, and altruism are different skills, and only trust was impacted

Potential mechanisms

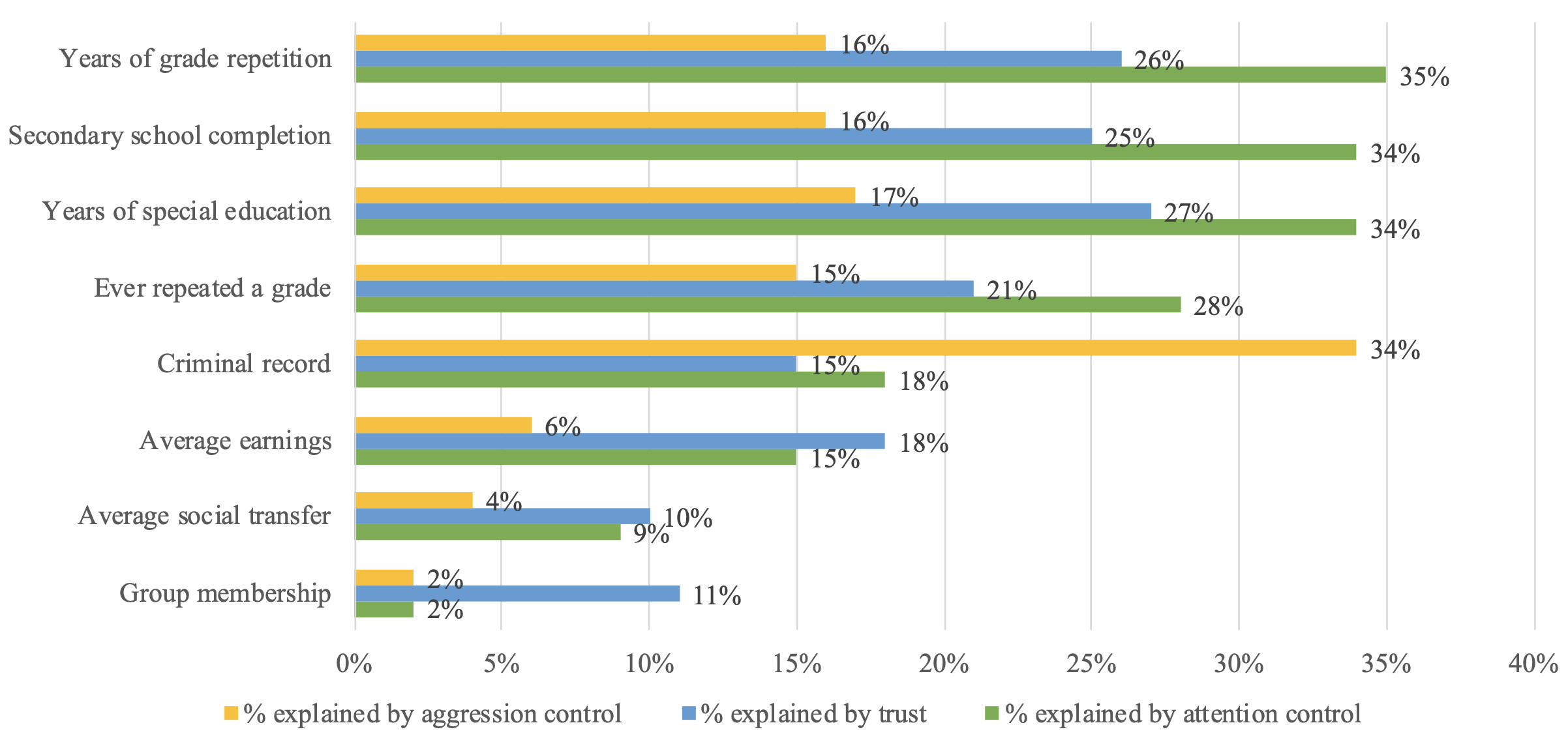

While we cannot isolate the causal effect of the changes in different skills because of the correlation between the skills, there are hints about which skills are most closely related to which outcomes. Figure 4 shows the per cent reduction in the treatment effect when each skill is controlled for – that is, how much of the treatment impact can be explained by the changes in each skill. Attention control explains the highest proportion of school performance and secondary school completion. The changes in aggression control explain the largest proportion of reduced crime. Trust explains the most of labour market outcomes and group membership.

Figure 4 Percent of impacts explained by changes in impacted skills

A sound investment

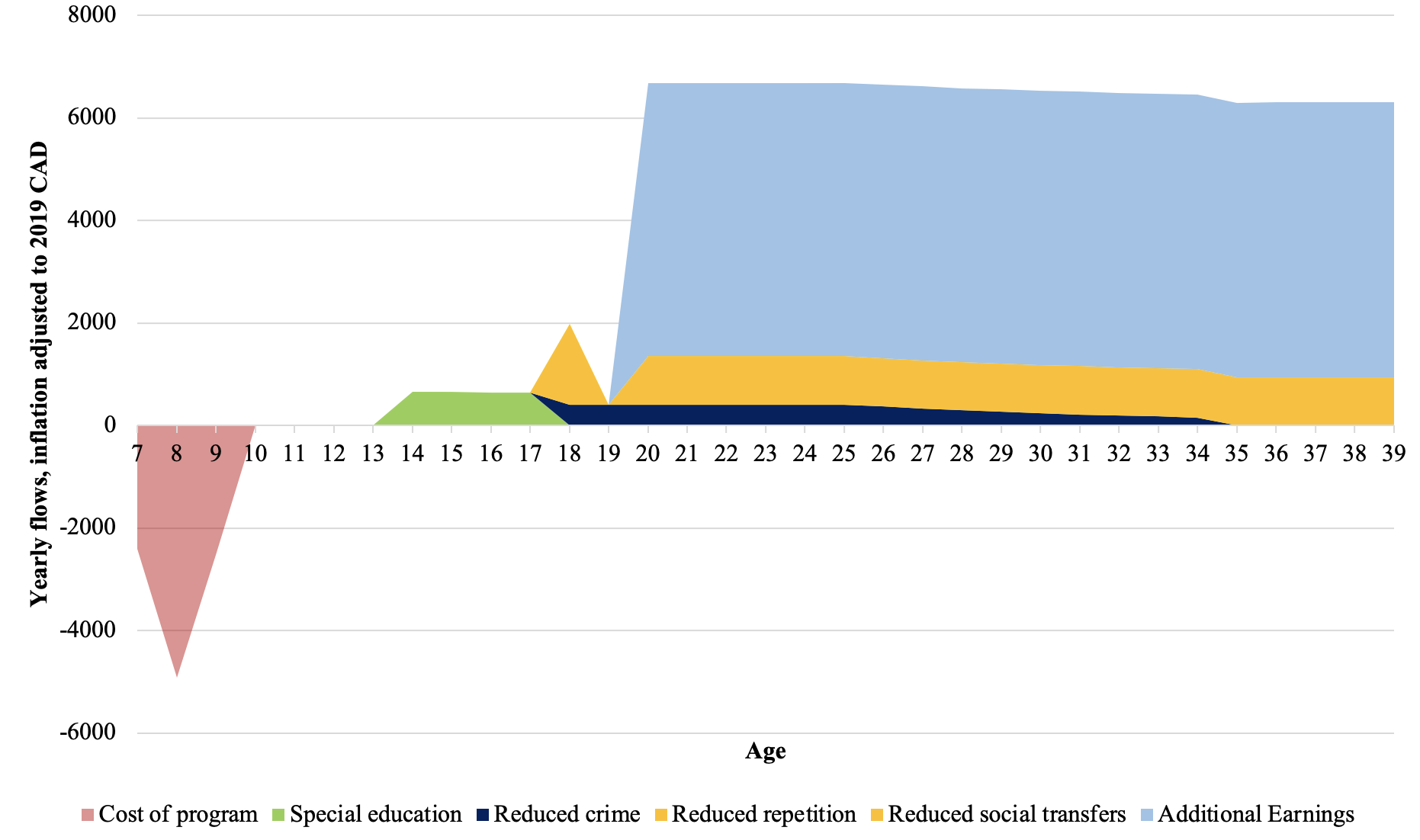

Over the years, the initial investment in training paid off for the public in several ways. Reduced school repetition and special-education assignment meant lower education costs. Reduced crime meant fewer arrests, lower policing and administrative costs, and certainly reduced direct cost of crimes to victims (which we are unable to measure and do not include – indicating that our estimates are likely to be a lower bound). Reduced dependence on social transfers meant fewer welfare payments by the state.

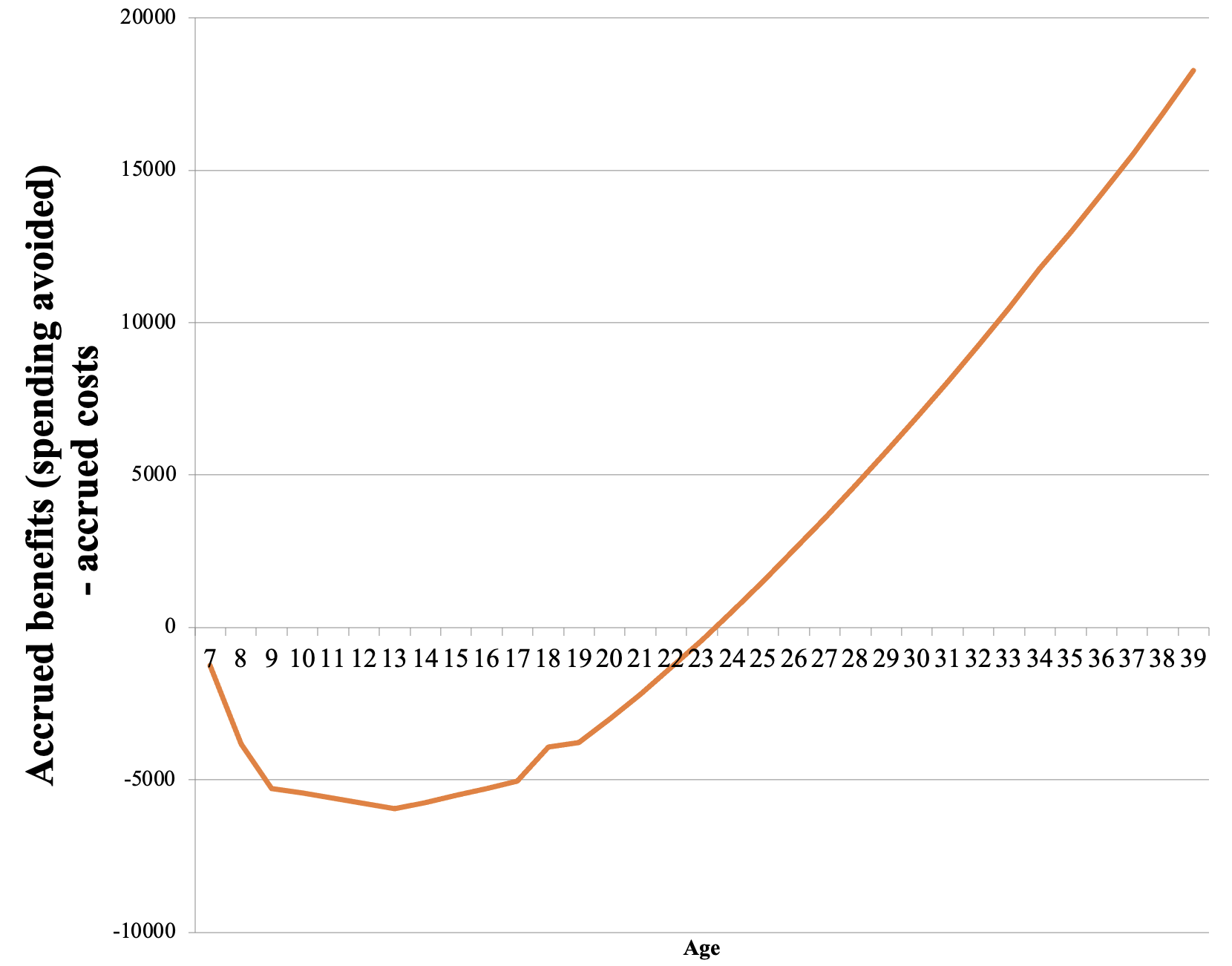

In our paper, we offer several ways of estimating the overall benefit of the programme, all of which suggest that there are very high returns, even when the individual’s labour market returns are excluded. We estimate that if this had been a government programme, the government would have broken even – due to spending avoided – by the time the boys had reached age 24 (Figure 5).

Figure 5 The cost of the programme compared to the benefits

(a) Cost of programme

(b) Overall benefit

Since this programme took place in Montreal in the 1980s, these estimates may not be perfectly transferable to other contexts today. However, it is clear that involving children in training programmes specifically targeting the development of social skills and self-control can have a long-term impact on the participants and society, reducing criminality and increasing other positive outcomes like employment, education, and social capital.

References

Algan, Y, E Beasley, S Côté, J Park, R E Tremblay and F Vitaro (2022), “The impact of childhood social skills and self-control training on economic and noneconomic outcomes: Evidence from a randomized experiment using administrative data”, American Economic Review 112(8): 2553–79.

Bailey, M J, B D Timpe and S Sun (2021), “Head Start’s long-run impacts on human capital and labour-market outcomes”, VoxEU.org, 6 June.

Deming, D (2017), “The growing importance of social skills on the labor market”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(4): 1593–640.

Elango S, J L García, J JHeckman and A Hojman (2016), “Early childhood education and social mobility”, VoxEU.org, 12 January.

Heckman, J J, S H Moon, R Pinto, P A Savelyev and A Yavitz (2010), “The rate of return to the High/Scope Perry Preschool Programme”, Journal of Public Economics 94(1–2): 114–28.

Heckman, J J (2017) “Intergenerational mobility”, VoxEU.org, 6 March.

Kocher, M, D Rützler, M Sutter and S Trautmann (2012), “Cognitive skills, self-control, and life outcomes: The early detection of at-risk youth”, VoxEU.org, 16 April.