The end of the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) amid increasing inflation has brought again to the fore fiscal concerns in the euro area that remained dormant during the pandemic (Corsetti and Codogno 2021). High debt and its sustainability are at the core of those concerns and feed into the policy debate. On the fiscal side, discipline and adjustment are rising in the European discussion. On the monetary side, the ECB is navigating a narrow path, tightening monetary policy and attempting to dispel fears of diverging financing costs and fragmentation within the euro area (Reichlin et al. 2022). Against this backdrop, understanding the impact of PEPP and – even so more at the current juncture – of its termination on debt sustainability is a central policy issue.

In this column, we analyse the effects of PEPP on the debt dynamics of highly indebted eurozone countries. We apply the methodology developed in Alberola et al. (2022) that embeds the estimation of the spread compression induced by the asset purchases in a stochastic debt sustainability analysis (DSA).

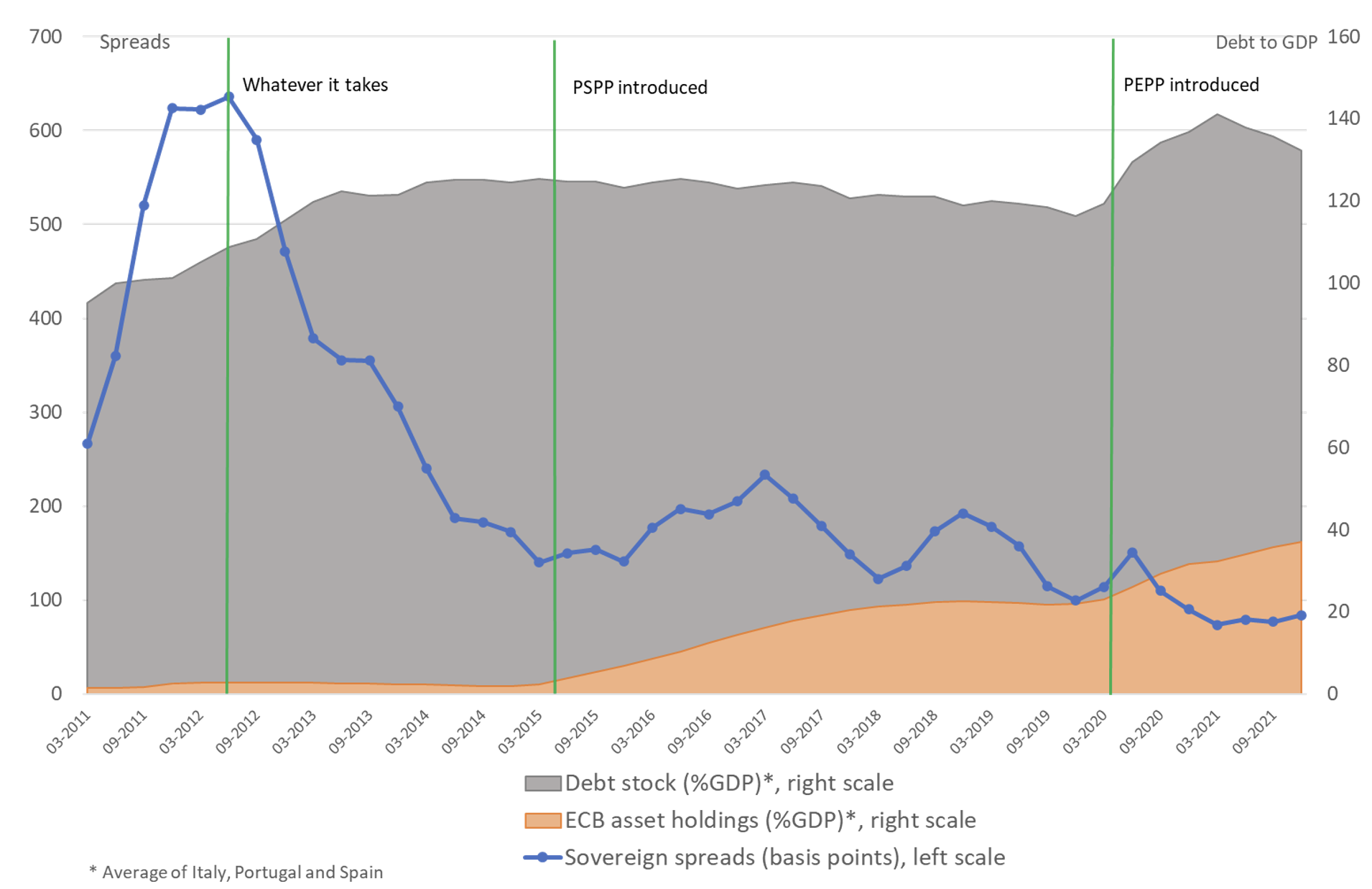

Euro area sovereign debt has reached new peaks after the pandemic. The average debt-to-GDP ratio of the three large highly indebted countries that we analyse – Italy, Spain, and Portugal – surged 25 points in 2020 to surpass 130% of GDP (Figure 1). In contrast to the euro crisis of 2012, sovereign spreads only increased briefly at the onset of the pandemic to decrease sharply afterwards. The unprecedented interventions by the ECB, especially through the PEPP, were key to this outcome; the programme also created the fiscal space to implement a massive fiscal expansion to face the crisis at the national and EU-wide level. As the programme expired, debt sustainability concerns have resurfaced amid increasing spreads, inflation, and a tightening of monetary policy.

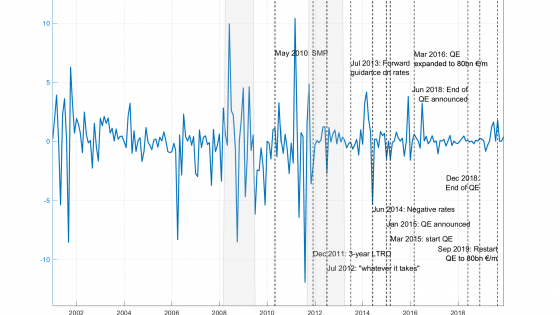

Figure 1 Announcements and implementation of ECB asset purchases have an impact on spreads

This is not the first time that the ECB unconventional monetary policies have contributed decisively to reducing sovereign spreads amid debt surges. The level of debt is an important determinant of debt sustainability and sovereign spreads reflect sustainability concerns (Reinhart et al. 2003, Goshn et al. 2013). Spreads tend to reflect debt evolutions: they jumped during the first debt surge after the great financial crisis, narrowed as debt receded, and spiked again with the pandemic. But the relationship between debt and spreads is not always tight because other factors come into play, such as expectations on fiscal discipline, political risk, or … unconventional monetary policy, which has played a central role in the last decade.

Figure 1 also displays the holdings of sovereign debt on the ECB balance sheet and the main milestones regarding ECB asset purchases. Draghi’s famous “whatever it takes” speech in 2012 had a large impact on spreads, without even starting the announced purchase programme (OMTs). The start of other programme (PSPP) in 2015 had initially a significant impact, but the effect faded as the programme advanced. Signalling effects have been relevant (Altavilla et al. 2020), but in practice it is complex to disentangle them from direct effects and in our analysis we stick to the latter.

The PEPP was launched in March 2020 and has resulted in huge purchases, with the initial envelope of €750 billion expanding to €1,850 billion. At its peak (in September 2021), the ECB’s asset purchases had covered the full issuance of new debt in the euro area since the onset of pandemic and represented 35% of the debt stock. The launching of PEPP more than reversed the spike in spreads when the pandemic shock hit, although the compression of spreads also diminished as the programme progressed. Towards the end of 2021, as signals of PEPP termination became clearer, spreads started to increase. The upward drift has continued after the PEPP has finished at the end of 2022 although reinvestment of maturing debt has been announced to continue until the end of 2023. Then, presumably, a passive unwinding will start: holdings at the ECB balance sheet will fall as the debt matures.

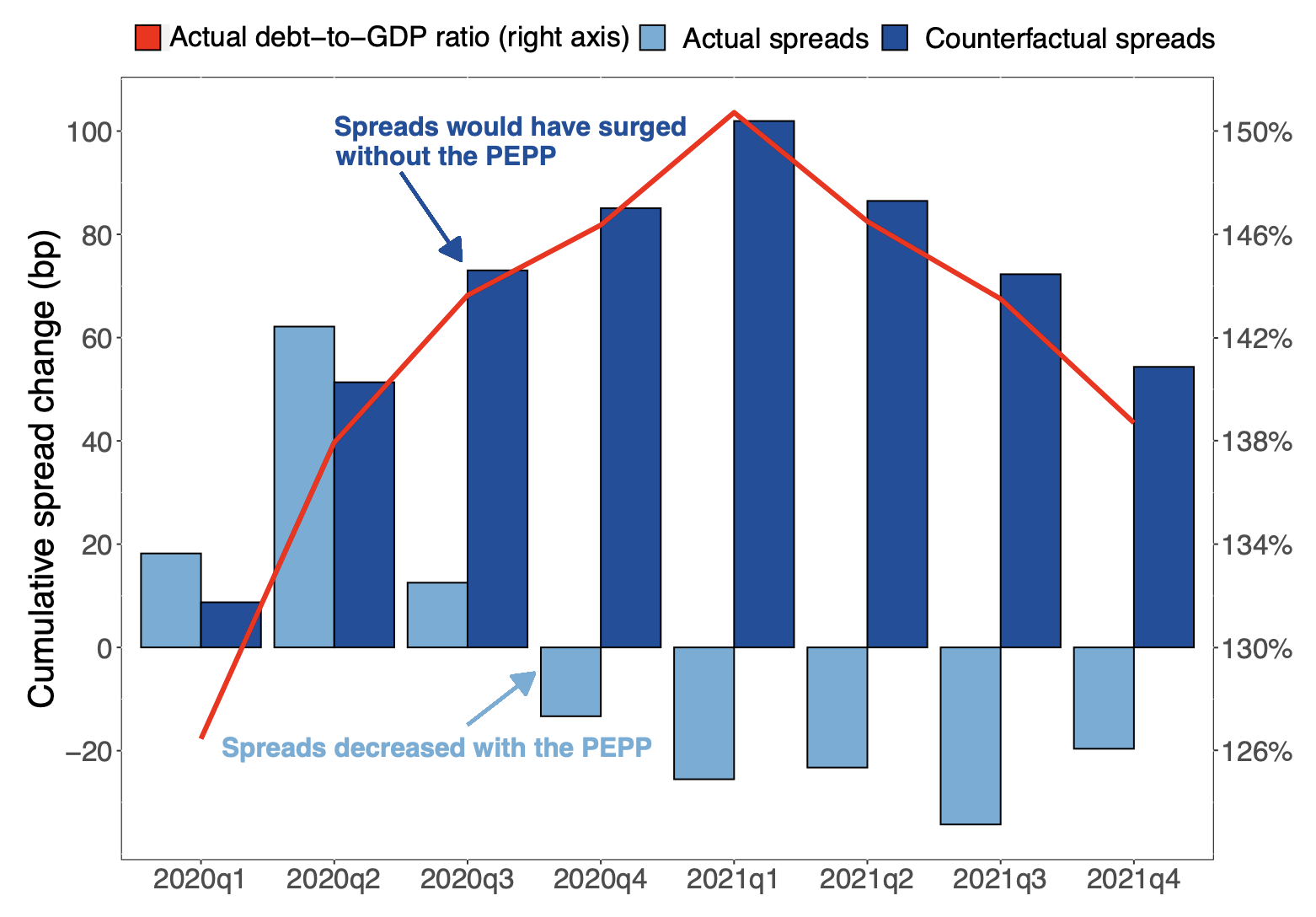

To estimate the impact of the PEPP purchases on sovereign spreads, we consider the surge of debt during this period and assess where spreads would have been without PEPP (Figure 2). To build this counterfactual, we estimate the effect of the debt-to-GDP ratio on sovereign spreads of highly indebted euro area countries in the pre-pandemic period. More precisely, we run a panel of the difference between the 10-year bonds of those countries and the German Bund for the period 2015Q1 to 2020Q1. We estimate that each percentage point of debt to GDP adds 3.2 basis points to the spreads of highly indebted sovereigns.

Figure 2 Without the PEPP, euro area spreads would have been higher

Figure 3 shows the counterfactual spread for the average of Italy, Spain, and Portugal. The jump in debt at the onset of the pandemic would have increased the average spread up to 100 basis points. Instead, spreads narrowed when the PEPP started.

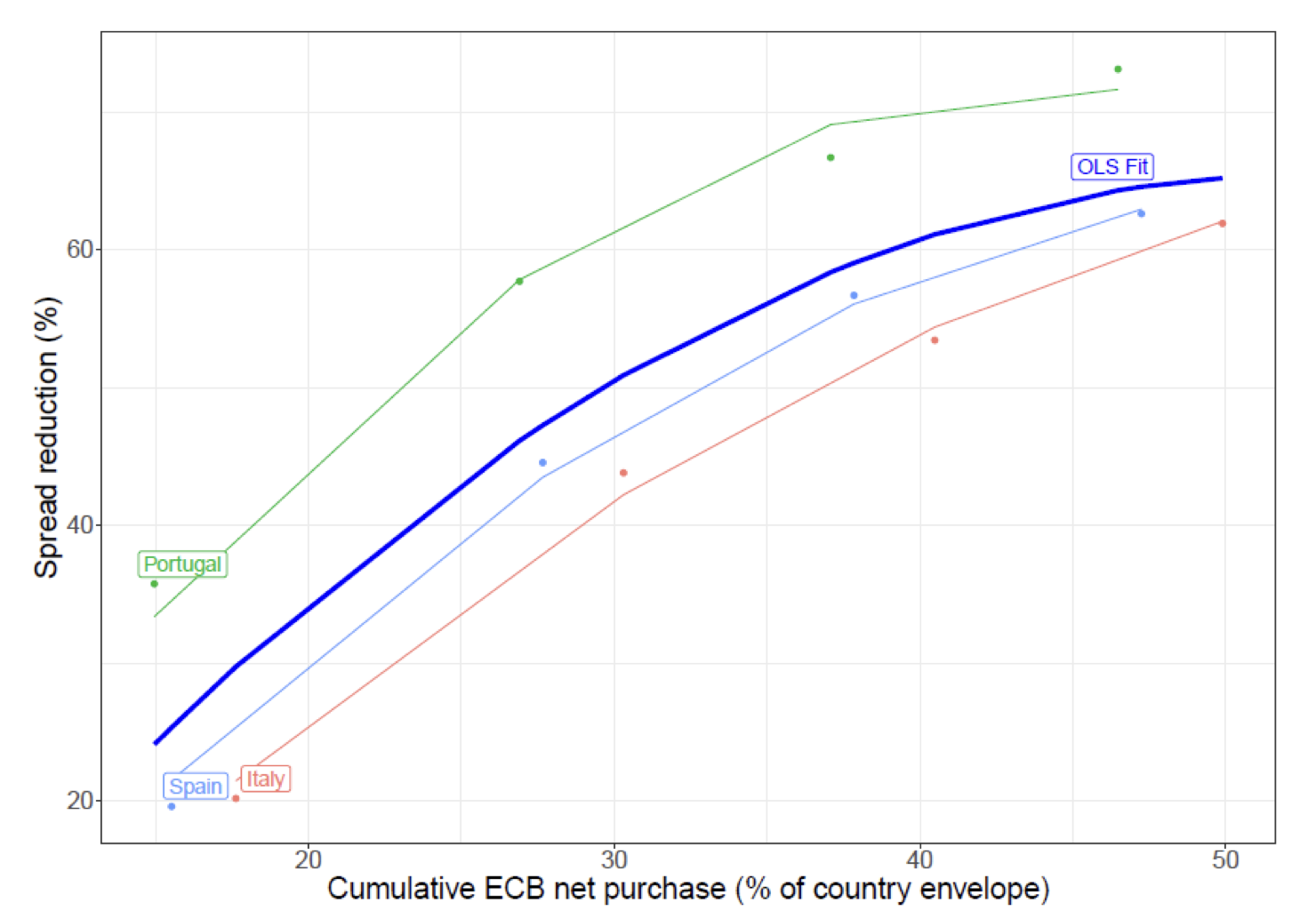

Figure 3 Purchases compressed spreads, albeit at a declining rate

Using the counterfactual for each country, we calibrate the spread compression (i.e the difference between the counterfactual spreads and the observed spreads) as a function of the cumulated asset purchases. The curve in Figure 3 shows a strong negative relation that diminishes with the size of cumulated purchases, capturing the fading impact of purchases.

These estimates allow us to explore the impact of PEPP – and its conclusion and eventual reversal – on debt sustainability. We just need to incorporate the spread compression function into the stochastic DSA model of Zenios et al. (2021) enhanced with a monetary policy block. The stochastic approach of our DSA model allows to draw estimates of debt sustainability at different probability levels. Debt is deemed sustainable when the debt trajectory is stable or decreasing at a medium-term horizon (10 years) with a high probability (0.75).

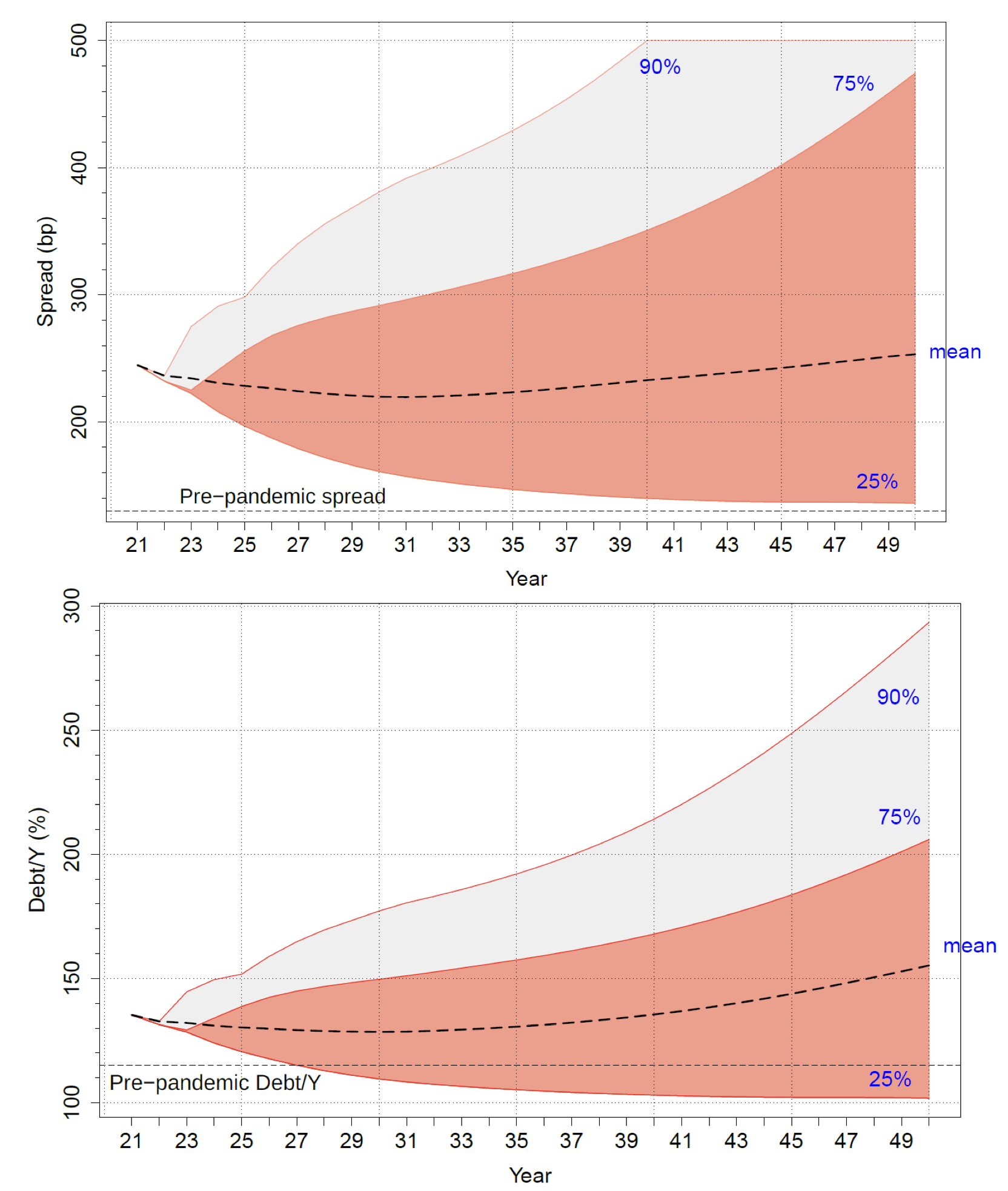

The benchmark for comparison is the counterfactual. The fan charts in Figure 4 show the spread and debt trajectories without PPP at different levels of probability. We observe (top panel) large and increasing risk premia, reminiscent of the euro area crisis, that fail to return to the pre-pandemic level and increase in the long run. The debt ratio (bottom panel) remains above the pre-pandemic level and is increasing with high probability at the 10-year horizon. Without the PEPP, the debt dynamics would likely have been explosive.

Figure 4 The counterfactual: Spread and debt trajectories without the PEPP

Source: Alberola et al. (2022).

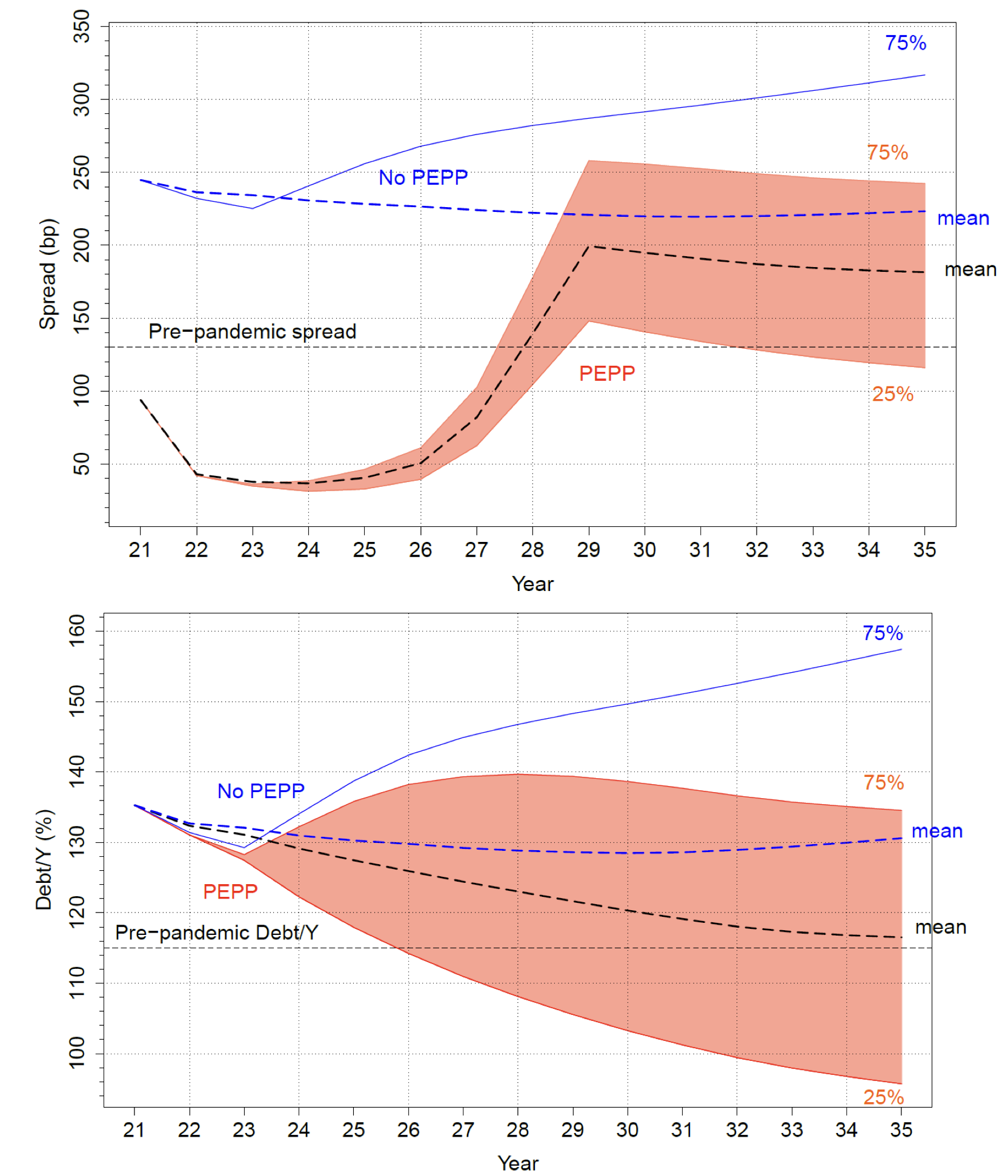

The outcome is very different when we account for the PEPP (Figure 5): while the programme was active, it reduced spreads according to the spread compression estimated function. Differences in the debt trajectories relative to the counterfactual (blue lines) are small in this period. Once the PEPP has been fully implemented, but before unwinding commences (the current situation), spreads are stable and debt decreases with a high probability due to GDP growth. When the unwinding starts the compression curve is rolled back and spreads widen.

We assume the unwinding starts in 2024 – as currently announced – and lasts five years. Yet, debt dynamics remain overall favourable: at mean values, debt follows a descending trajectory and, with a 75% probability, debt stabilises in the medium run and then falls, implying sustainability.

Figure 5 PEPP reduces spreads and renders debt sustainability, even with unwinding

Source: Alberola et al. (2022).

Another way to interpret our results is that fiscal policy has been – and will be – less constrained thanks to PEPP. Could fiscally vulnerable countries in the euro area have afforded large fiscal stimuli without PEPP? Presumably not. Amid market turbulence, they would have been forced to a fiscal adjustment that would have deepened the recession and hampered the recovery. The contrast is dramatic looking ahead: without the programme, the gross financing needs as a proportion of GDP would be 4.4% for the representative country in the medium to long run. Indeed, we estimate that a required increase of the fiscal primary balance of 1.3 for 15 years would follow to keep debt sustainable. In contrast, with PEPP, gross financing needs fall to 3% and the fiscal effort to bring down debt is manageable.

All in all, PEPP substantially improves debt dynamics and its beneficial effects last well beyond the end of the programme. PEPP has allowed a critical sustainability situation to be overcome and its unwinding should not jeopardise sustainability under normal circumstances.

These conclusions are reinforced when noting that the unwinding scenario is rather stringent, and not only because it is quite swift. First, the impact of unwinding on spreads is symmetrical to the purchase of assets, but within normal market conditions, we can expect that it would be more muted. Second, if markets turn volatile, the unwinding period could be extended or other instruments – such as Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) recently launched by the ECB to avoid market fragmentation – could be used. Third, the spike in inflation can have a favourable, albeit transitory, effect on debt dynamics if it results in lower real interest rates.

Hence, our analysis is biased towards a bad case scenario.

Things could go wrong, though. Unwinding has not started and the TPI has not been tested – neither the resolve nor the effectiveness of the ECB to avoid fragmentation in an inflationary environment. If inflation becomes entrenched, a severe monetary policy tightening could follow and real rates could go up, negatively affecting growth and debt dynamics. Bond markets could spiral out of control. Against this backdrop, tensions between governments and the ECB may arise. In this context, while we sustain that the PEPP has been necessary and beneficial, it has also entrenched the fiscal–monetary policy nexus, complicating the job of the ECB at this complex juncture.

References

Alberola, E, G Cheng, A Consiglio and S Zenios (2022), “Debt sustainability and monetary policy: the case of ECB asset purchases”, BIS Working Paper 1034.

Altavilla, C, R Gurkaynak, R Motto and G Ragusa (2020), “Financial market reactions to monetary policy signals”,VoxEU.org, 3 August.

Corsetti, G and L Codogno (2020), “Post-pandemic debt sustainability in the EU/euro area: This time may (and should) be different”, VoxEU.org, 18 September.

Ghosh, A R, J I Kim, E G Mendoza, J D Ostry and M S Qureshi (2013), “Fiscal Fatigue, Fiscal Space and Debt Sustainability in Advanced Economies”, The Economic Journal 213(566).

Reichlin, L, G Ricco and A Tuteja (2022), “The two-dimensional feature of ECB monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 16 April.

Reinhart, C M, K S Rogoff and M A Savastano (2003), “Debt Intolerance”, Brookings Papesr on Economic Activity 1.

Zenios, S, A Consiglio, M Athanasopoulou, E Moshammer, A Gavilan and A Erce (2021), “Risk management for sustainable sovereign debt financing”, Operations Research 69: 755–773.