The slew of sanctions by the US and the EU after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were anticipated to bring about a significant economic downturn of the Russian economy (Ongena et al. 2022). This fall failed to materialise in 2022, largely on the wings of large oil and gas revenues that have been channelled into subsidies for some industries and in the development of import-substitution mechanisms (Nigmatulina 2022).

There are, however, long-term debilitating effects of the sanctions on Russia’s economic development. Advisors and business leaders in Putin’s entourage who espoused market economy views have left Russia, resigned from the government, or distanced themselves from the President. These political exits have shifted the apex of Russian economic policies towards purveyors of closed-economy ideology.

This policy shift towards autarky, precipitated by the sanctions but embraced by the new Russian political elites, has precedent in Russian history. The presence of such inward-looking economic ideology in Tzarist Russia motivated Gerschenkron’s Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective (1962), which recognises that political elites often oppose rather than promote economic development. Gerschenkron’s analysis rings true in today’s Russia.

The likely outcome of this autarkic model is a prolonged period of economic stagnation, with significant public resources flowing into the hands of few dozen politically connected families (Djankov 2023). Russia’s entrepreneurial class becomes thinner still, with hundreds of thousands of skilled professionals leaving the country in search of opportunity.

Power dynamics in post-sanctions Russia

The waves of Western sanctions after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine markedly changed the constitution of President Putin’s inner circle, built over two decades in power (Djankov 2015). The market economics bloc of the president’s advisors lost ground after the resignation of the former minister of finance Alexei Kudrin as president of the Accounts Chamber (TASS 2022) and the emigration of Anatoly Chubais, presidential envoy for energy policies (Seddon 2022). The influence of another group of former market economics supporters – President Putin’s St. Petersburg oligarch friends – has also dissipated with the war. Since put under sanctions, these individuals have tried to convince European and American institutions that their closeness to Putin is exaggerated and long gone (Reuters 2022).

Instead, four other groups of confidants or members of the security or military establishment have gained influence with the President. These groups support Russia’s invasion, while some go further to incite imperial ambitions beyond Ukraine. In all cases, they publicly promote a dominant role of the state in the Russian economy, including through nationalisation.

The first group is formed around the head of Russia’s Security Council. The group includes the heads of the various branches of security services, as well as some newly minted oligarchs who have benefited from the sanctions by receiving import-substituting subsidies (Djankov 2023).

The second group is formed around the head of the presidential administration. This group controls Russia’s nuclear power sector. Members of this group are vocal about the need for nationalisation of private assets belonging to businesspeople who do not publicly support the war (McKay et al. 2022). This approach has precedent. Oligarchs aligned with this group took over the majority of private corporate assets in annexed Crimea after 2014, including the retail banking network, the main port, and airport in the occupied territory (Tumakova et al. 2023).

A third emerging group is connected to President Putin by joint work with the KGB in Dresden (Djankov 2023). Its members include intelligence and counterintelligence functionaries and their scions who have benefited from family connections to amass significant wealth. The fourth group of ‘super-hawks’ has formed around the owner of the Wagner mercenary army Yevgeny Prigozhin and Dmitry Medvedev, the former President and Prime Minister. Members of these two groups advocate further expansion of Russia’s military engagements into other members of the former Soviet Union and even Western Europe (Mackinnon 2022).

While in competition for President Putin’s favour, these four groups have a convergent economic view: they advocate state ownership of strategic assets, including through nationalisation of the property of ‘unfriendly’ individuals and foreign companies and a return to an autarkical economy.

Inward-looking Russia in historical perspective

Under President Putin’s leadership – the longest of either the Soviet or modern Russian era – the Russian economy has shifted from crony capitalism and open international trade to state capitalism and autarky (Aven 2015, Djankov 2015), a process that has ramped up in the last year. There are several episodes reminiscent of the current post-sanctions period in Russian and Soviet history. In 1725, Tzar Peter the First passed without an apparent heir, plunging the Russian Empire into an era of autarkic policies. A similar economic policy shift was observed in 1924-1927 after the death of Lenin and in 1982-1985 after the death of Leonid Brezhnev. In all three cases, unexpected figures ultimately rose to power, people who opposed change and advocated for the development of an autarkical society (Gerschenkron 1970, Mosse 1992, Acemoglu and Robinson 2006).

The inclination to resort to inward-looking economic policies is not manifested only during sudden political crises in Russia. During the 30-year reign of Nikolai I (1825 to 1855) a single railway line was built in the country. “Economic development – elsewhere in Europe this was the age of early industrialization and railway construction – was deliberately held back, since it was understood that industrial development might lead to social and political change” (Mosse 1992). When industrialisation in Russia finally got underway after the Crimean War, the fears of the elites were confirmed: industrialisation brought social turbulence in urban centres, and political and social change, culminating in the 1905 Revolution (McDaniel 1988, Acemoglu 2003).

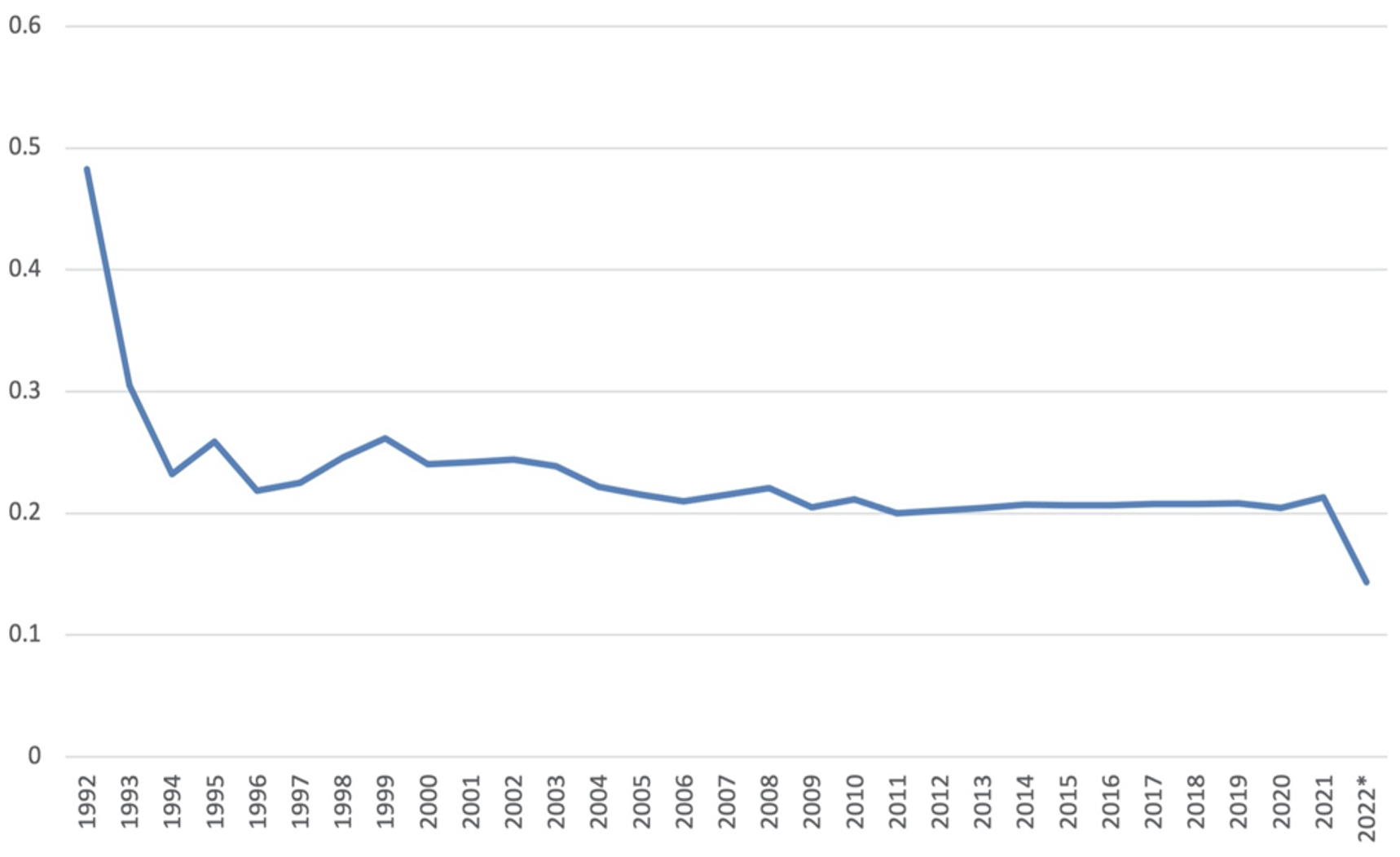

The imposition of western sanctions on Russia in 2022 had a similar effect on the survival instincts of Russia’s political elite. New economic policies are aimed at self-reliance, much like in past historical episodes. This self-reliance is blamed on the exit of western companies from the Russian market, bans of various exports and imports, and the dissolution of contracts for western technology. Beyond these reasons lie personal interest in accumulating political clout and family wealth. As a long literature starting with von Mises (1944) suggests, however, that autarkic economies lack vitality. Coupled with the western sanctions in many sectors, inward-looking economic policies have brought down imports by 19.2% year-on-year in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Plummeting imports in 2022 (as a share of GDP)

Source: World Bank’s World Development Indicators, accessed 1 March 2023.

The only development that can challenge the support for autarky is the lack of visible victories at the war front in Ukraine. This pattern was observed during WWI: the socialist revolution was impossible in 1914 or 1916, when the Russian army had military victories, but a series of defeats at the front led to the successful revolt in 1917.

Implications

The history of autarky in 19th century Russia and subsequent episodes in Soviet Russia illustrate the contradictions that political elites faced in promoting economic development. Similar dynamics are at work in today’s Russia, with a shift towards autarky that is embraced by all political groups in close contact with President Putin.

This shift in economic policy is not met with much opposition. The middle class that has the most to gain from the open market economy has been emaciated. As a result of the sanctions and threat of closed borders, part of the Russian middle class emigrated in early 2022, while others went into the service of the new oligarchs who benefit from the autarkical model. The mobilisation actions in September 2022 led to another wave of middle-class professionals leaving Russia.

Western sanctions are achieving their stated goal of weakening the Russian economy and bringing about economic backwardness. This weakening is channelled through a closing of the economy, a dynamic that hurts the middle class as well. How far this process goes depends primarily on developments at the war front in Ukraine. The faster the defeat of Russian forces, the more chance there is that Russia’s economy opens up again.

References

Acemoglu, D (2003), “Why Not a Political Coase Theorem?”, Journal of Comparative Economics 31(4): 620– 52.

Acemoglu, D and J Robinson (2006), “Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective”, American Political Science Review 100(1): 115-131.

Aven, P (2015), "1990s: Back to the USSR?", The World Today 71(3): 47-62.

Djankov, S (2015), “Russia's Economy under Putin: From Crony Capitalism to State Capitalism”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Briefs 15-18, September.

Djankov, S (2023), “How the war is increasing inequality in Russia”, VoxEU.org, 9 February.

Gerschenkron, A (1962), Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective, Harvard University Press.

Gerschenkron, A (1970), Europe in the Russian Mirror: Four Lectures in Economic History, Cambridge University Press.

Mackinnon, A (2022), “The Fall and Fall of Dmitry Medvedev”, Foreign Policy, 23 June.

McDaniel, T (1988), Autocracy and Modernization in Russia, Princeton University Press.

McKay, B, T Grove and R Barry (2022), “The Russian Billionaire Selling Putin’s War to the Public”, Wall Street Journal, 2 December.

Mosse, W (1992), An Economic History of Russia, 1856–1914, I.B. Taurus Press.

Nigmatulina, D (2022), “How US sanctions increased the economic activity of sanctioned Russian firms”, VoxEU.org, 19 November.

Ongena, S, A Pestova and M Mamonov (2022), “The price of war: Macroeconomic effects of the 2022 sanctions on Russia”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.

Reuters (2022), “Putin Ally Timchenko Resigns From Novatek Board”, 21 March.

Seddon, M (2022), “Top Kremlin official Anatoly Chubais quits as Putin's climate envoy”, Financial Times, 23 March.

TASS (2022), “Kudrin accepts Yandex’s corporate leadership position offer”, 5 December.

Tumakova, I, I Murtazin and I Zhilin (2023), “It’s More Fun to Live Together”, Novaya Gazeta, 6 February (in Russian).

Von Mises, L (1944), Omnipotent Government, Lowe Press (2008).